Gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer mortality and is frequently associated with nutritional disorders, the detection and proper management of which can contribute to improving quality of life and survival. Being aware of the consequences and of the different treatments for this neoplasm allows us to offer an adequate nutritional approach. In surgical candidates, integration into ERAS-type programs is increasingly frequent, and includes a pre-surgical nutritional approach and the initiation of early oral tolerance. After gastrectomy, the new anatomical and functional state of the digestive tract may lead to the appearance of “post-gastrectomy syndromes”, the management of which may require diet modification and medical treatment. Those who receive neoadjuvant or adjuvant antineoplastic therapy benefit from specific dietary recommendations based on intercurrent symptoms and/or artificial nutrition. In palliative patients, the nutritional approach should be carried out while respecting the principle of autonomy and weighing the risks and benefits of the intervention. The objective of this review is to highlight the importance and role of nutrition in patients with gastric cancer and to provide guidelines for nutritional management based on the current evidence.

El cáncer gástrico supone la tercera causa de mortalidad por cáncer y se asocia con frecuencia a alteraciones nutricionales cuya detección y apropiado manejo pueden contribuir a mejorar la calidad de vida y la supervivencia. Conocer las consecuencias y complicaciones de los distintos tratamientos de esta neoplasia permite ofrecer un adecuado apoyo nutricional. En candidatos a cirugía, cada vez es más frecuente la integración en programas tipo ERAS, que contemplan el abordaje nutricional prequirúrgico y el inicio de la tolerancia precoz, entre otros. Tras la gastrectomía, la nueva situación anatómica y funcional del tracto digestivo puede conllevar la aparición de “síndromes post-gastrectomía” cuyo manejo puede requerir modificaciones de la dieta y tratamientos médicos. Aquellos que reciben terapia antineoplásica neoadyuvante o adyuvante se benefician de recomendaciones dietéticas específicas según la sintomatología intercurrente y/o de nutrición artificial. En pacientes en situación paliativa, el tratamiento nutricional se debe realizar respetando el principio de autonomía y sopesando el riesgo-beneficio de la intervención. El objetivo de esta revisión es destacar la importancia y el papel de la nutrición en los pacientes con cáncer gástrico y facilitar unas pautas de manejo nutricional según la evidencia actual.

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignant tumour worldwide, with nearly one million new cases annually, and the third leading cause of cancer mortality globally.1 It is a neoplasm that is frequently associated with malnutrition and other nutritional deficiencies, the detection and proper management of which can contribute to improving the quality of life and survival of these patients.

The most common histological type is adenocarcinoma (ADC), which represents 85% of cases,2 with others such as lymphoma, sarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumours or neuroendocrine tumours being less common. From an anatomical perspective, it can be classified as cardia (from the gastroesophageal junction) and non-cardia (distal).

The exact origin of gastric cancer is unknown. However, there are several risk factors that predispose its appearance. One of the most significant is Helicobacter pylori infection, whose detection and treatment have helped reduce the incidence of distal carcinoma.1,3 Other known factors include advanced age, male gender, obesity, tobacco, alcohol, low socioeconomic status, previous gastric surgery, pernicious anaemia or Epstein-Barr virus infection.1,3 Gastroesophageal reflux disease increases the risk of cardia GC, the incidence of which has increased in recent years.3 Dietary factors, such as excessive consumption of salt and smoked or cured products, and the intake of processed meat rich in N-nitroso compounds, have also been related to GC.3

Although most GC is sporadic, there is a genetic predisposition of varying magnitude, with inheritance being responsible for a small percentage of the total.3 This is the case for hereditary diffuse gastric cancer and gastric ADC associated with proximal polyposis in the stomach.

GC treatment must be established in a multidisciplinary manner2 taking into account the patient's clinical situation (age, comorbidities, functional status, etc.) and factors related to the tumour itself (location, histology, stage, etc.). In gastric ADC without distant involvement, surgery with total or partial gastrectomy and lymphadenectomy is the only curative treatment.2,4 The decision for complementary chemotherapy (CT) or chemoradiotherapy (CT-RT) in the different phases of the process depends on clinical, radiological and pathological factors. In metastatic disease, CT is the treatment of choice,2 associated with other procedures to alleviate symptoms and/or prolong survival. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has been used in selected patients with peritoneal disease.5

Malnutrition in gastric cancerSome studies have found the prevalence of malnutrition in GC to be around 60%,6,7 although it varies widely depending on the tumour stage, type of treatment received and nutritional assessment (NA) tool used.

Malnutrition in these patients, as with other oncological processes, results in a worse prognosis and quality of life, as well as a negative clinical impact (higher rate of infections, toxicity of treatments, complications, hospital stay, etc.) and financial impact.8,9

The origin of malnutrition is multifactorial. There are factors common to other neoplasms, such as anorexia, catabolism and inflammation, but also related to the location of the tumour (dysphagia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, intestinal obstruction) and its treatment (dumping syndrome [DS], exocrine pancreatic insufficiency [EPI], mucositis, diarrhoea, etc.).

Nutritional diagnosis in gastric cancerThe high prevalence of malnutrition and its negative impact on patients with GC means early detection and treatment are necessary.9

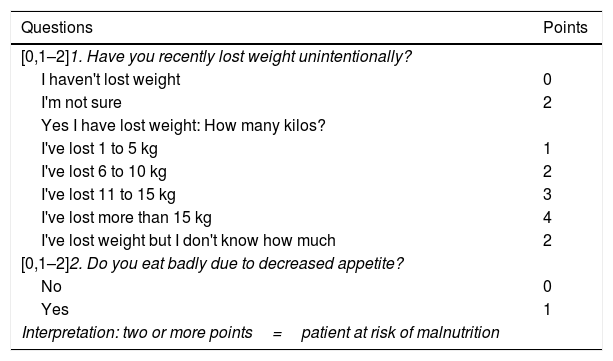

Nutritional screening makes it possible to select those patients who would benefit from a more comprehensive NA. In this sense, both national and international guidelines recommend including it as one more tool in the management of cancer patients.9–12 Following recommendations from the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), nutritional screening should be carried out at diagnosis and repeated periodically depending on the clinical course.10 Screening is recommended to include: monitoring of intake, as well as changes in weight and body mass index (BMI).10 Across Spain, the tool of choice is the Malnutrition Screening Tool (MST),11,13 which asks about appetite and involuntary weight loss (Table 1).14

Malnutrition screening tool.14

| Questions | Points |

|---|---|

| [0,1–2]1. Have you recently lost weight unintentionally? | |

| I haven't lost weight | 0 |

| I'm not sure | 2 |

| Yes I have lost weight: How many kilos? | |

| I've lost 1 to 5 kg | 1 |

| I've lost 6 to 10 kg | 2 |

| I've lost 11 to 15 kg | 3 |

| I've lost more than 15 kg | 4 |

| I've lost weight but I don't know how much | 2 |

| [0,1–2]2. Do you eat badly due to decreased appetite? | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes | 1 |

| Interpretation: two or more points=patient at risk of malnutrition | |

Taken from Ferguson et al.14

In the event of a positive screening result, performing a complete NA is required, since there is no specific tool for GC. The NA should be based on an adequate anamnesis, physical examination and the use of complementary tests that provide information about the following:

- •

Symptoms that interfere with intake.10,11 Early GC can progress without symptoms. However, as the disease progresses, it is common to detect anorexia, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, a feeling of fullness with early satiety, nausea and vomiting (which are due to retention if there is severe pyloric stenosis). There may be gastrointestinal bleeding due to bleeding from the tumour itself or vascular invasion. Patients with gastroesophageal junction neoplasm often report progression to dysphagia for solids.

- •

Qualitative and quantitative modifications of intake.10,11

- •

Variations in body weight.10,11 Involuntary weight loss, even with a normal or high BMI, is a factor for poor prognosis and mortality in cancer patients.8 It has been documented as the most common symptom in GC.15 In the classic study by Dewys et al.,16 >80% of patients with GC experienced weight loss, with >60% of subjects experiencing greater than 5% weight loss.

- •

Loss of muscle mass and fat, as well as the presence of oedema or ascites that can interfere with the interpretation of body weight.10,11

- •

The degree of systemic inflammation, where albumin levels along with C-reactive protein serve as markers of inflammation.9,11,12

- •

Assessment of functional status using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) scale, the Karnofsky Performance Status and other validated scales.11,12

The Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) or its variant the PG-SGA (Patient-Generated SGA) are considered the tools of choice for the NA of cancer patients.10–12

There is growing interest in the measurement of body composition in cancer patients10 and its possible prognostic value. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on GC demonstrated greater inpatient morbidity and mortality and lower survival associated with preoperative sarcopenia.17 This finding has also been related to an increase in infectious complications after gastrectomy.18 In their study on 138 patients with GC who underwent gastrectomy and with three-year follow-up of body composition, Park et al.19 found a continuous and progressive decrease in skeletal muscle mass, while fat mass decreased in the first year but then recovered. A low preoperative phase angle in GC patients older than 65 years was a predictor of the development of complications.20

An adequate NA must include the calculation of protein-caloric requirements. Indirect calorimetry is the method of choice to determine energy expenditure in cancer patients.9 Given the difficulties regarding its application and availability in routine practice, an energy intake of 25−30kcal/kg/day and protein intake of 1–1.5g/kg/day is recommended.9–12 The possibility of refeeding syndrome should be assessed and monitored, adjusting the initial caloric intake and its progression based on risk, as well as the need for micronutrient and electrolyte supplementation.9

Nutritional support in gastric cancer patientsThe high prevalence of malnutrition in this group reflects the high percentage of patients who will require nutritional support (NS). Segura et al. report that 77% of patients with advanced GC scored nine or more points in the “Scored PG-SGA”, which indicates the need for specialised and aggressive symptomatic and nutritional treatment.21

NS must follow the same premises that are recommended in other groups: if the gastrointestinal tract works and is accessible, use it. In patients with GC who are malnourished or whose requirements are not met with an ordinary diet (intake less than 50%–60% of actual requirements for one to two weeks, or no intake for more than one week),10,22 optimising oral intake, including the use of oral nutritional supplements (ONS), should be the first step.9–11 Enteral nutrition (EN) by tube/ostomy is reserved for situations in which requirements cannot be met with the previous measures or when it is required to bypass a tumour stenosis.9–11 Parenteral nutrition (PN) is necessary in cases of contraindication to EN, if there is no possibility of bypassing the stenosis or when requirements are not met.9–11

It should not be forgotten that NS accompanied by combined physical, aerobic and resistance exercise will foster the maintenance and recovery of muscle mass and strength,11,13 with the potential to improve pre-surgical functional status having been demonstrated in sarcopenic patients with GC,23 as well as quality of life.24

The clinical and functional status of the patient, the tumour stage and the GC treatment modality determine the NS. The features of the four main scenarios for this neoplasm are outlined below.

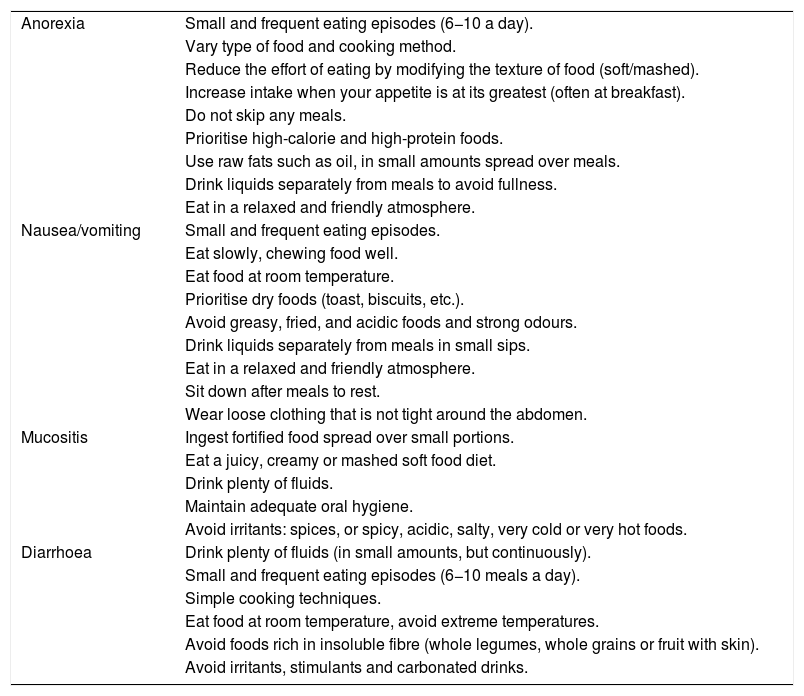

Nutrition in gastric cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapySide effects of antineoplastic drugs, such as diarrhoea, nausea-vomiting, anorexia, mucositis or dysphagia are common in GC. Their appearance limits intake, which has a negative impact on nutritional status.25 Their early detection and treatment are essential. In parallel to symptomatic treatment, diet and its consistency must be duly adapted according to the symptoms26,27 and grade of dysphagia (Table 2).

Nutritional recommendations according to the side effects of antineoplastic drugs.26,27

| Anorexia | Small and frequent eating episodes (6−10 a day). |

| Vary type of food and cooking method. | |

| Reduce the effort of eating by modifying the texture of food (soft/mashed). | |

| Increase intake when your appetite is at its greatest (often at breakfast). | |

| Do not skip any meals. | |

| Prioritise high-calorie and high-protein foods. | |

| Use raw fats such as oil, in small amounts spread over meals. | |

| Drink liquids separately from meals to avoid fullness. | |

| Eat in a relaxed and friendly atmosphere. | |

| Nausea/vomiting | Small and frequent eating episodes. |

| Eat slowly, chewing food well. | |

| Eat food at room temperature. | |

| Prioritise dry foods (toast, biscuits, etc.). | |

| Avoid greasy, fried, and acidic foods and strong odours. | |

| Drink liquids separately from meals in small sips. | |

| Eat in a relaxed and friendly atmosphere. | |

| Sit down after meals to rest. | |

| Wear loose clothing that is not tight around the abdomen. | |

| Mucositis | Ingest fortified food spread over small portions. |

| Eat a juicy, creamy or mashed soft food diet. | |

| Drink plenty of fluids. | |

| Maintain adequate oral hygiene. | |

| Avoid irritants: spices, or spicy, acidic, salty, very cold or very hot foods. | |

| Diarrhoea | Drink plenty of fluids (in small amounts, but continuously). |

| Small and frequent eating episodes (6−10 meals a day). | |

| Simple cooking techniques. | |

| Eat food at room temperature, avoid extreme temperatures. | |

| Avoid foods rich in insoluble fibre (whole legumes, whole grains or fruit with skin). | |

| Avoid irritants, stimulants and carbonated drinks. |

The use of ONS to support an insufficient oral diet is common in this group. They are often used as oral EN when they are the main source of nutrients in those who only tolerate fluids as a result of dysphagia due to tumour stenosis and/or mucositis. When the oral route fails to meet the patient's needs, EN by tube or ostomy should be considered. Jejunostomy should be considered in impassable stenosing GC and/or in those who require artificial nutrition in the medium-long term. Jejunostomy placement during GC staging laparotomy has been shown to be feasible and effective,28,29 although it is not without its complications.

Regarding the type of nutritional formula to be used, the ESPEN guidelines recommend selecting those enriched with omega-3 fatty acids (⌉3 fatty acids) in patients with advanced cancer undergoing CT treatment with weight loss, malnutrition or who are at risk, as appetite, intake, lean body mass and body weight improve.10

Routine use of PN is not recommended in patients on CT or CT-RT.10 Its indication should be reserved for when EN is insufficient or not feasible, since it has not been shown to be effective and may even be harmful in patients with a functioning gastrointestinal tract.10

Nutrition in gastric cancer patients who are candidates for surgeryThe need for NS in GC patients who are candidates for gastrectomy comprises three stages: pre-surgical, perioperative through the application of the ERAS (Enhanced Recovery After Surgery) protocol and postoperative (PO).

Pre-surgical nutritional treatmentFollowing the previously mentioned premises, which indicate prioritising oral and enteral optimisation over parenteral optimisation, it is recommended that NS be started without delay in malnourished patients and in those whose requirements are not being met. The duration of NS must be at least 7–14 days before the procedure.22

A study published by Kong et al.30 found that the use of ONS in severely malnourished patients with GC during the perioperative period decreased the incidence, severity and duration of PO complications. Regarding the use of immunomodulatory nutrition (IMN) formulas in surgical GC patients, we found a wide range of results, due in part to the variability in terms of composition and combination of immunonutrients, their dose and duration, as well as the time of the surgery and the nutritional status of the patients. However, the evidence points to a potential benefit in terms of reducing infectious complications and hospital stay.31,32 At a national and international level, the use of IMN formulas is recommended (arginine, ω3-fatty acids, nucleotides) in malnourished patients with upper gastrointestinal cancer who are candidates for surgery.10,12,22

PN is indicated in those patients with a contraindication to EN (intestinal obstruction),22 or, if after optimising EN, requirements are still not met.22

Implementation of ERAS programmesThe different scientific societies agree that the NS of GC patients should be implemented in the context of ERAS programmes.10,12,22 These encompass a series of strategies that are the responsibility of different specialists and involve various phases in the management of surgical patients, whose objective is to minimise the stress of the procedure, reduce complications and accelerate recovery. With regard to nutrition, the differential items are preoperative nutritional optimisation, reduction of preoperative fasting time and early oral tolerance.33 Experts recommend fasting for six hours for solid foods and two hours for clear liquids before gastric surgery.22,34 In addition, with a medium-high level of evidence, in the absence of contraindications, the intake of 250 cc of a 12.5% maltodextrin solution two hours before the procedure is recommended,34 which should be applied on a case-by-case basis and with caution in patients with dysphagia or gastroparesis.22,34 According to the ESPEN guidelines, the use of IMN formulas in the context of ERAS programmes is an area that requires further investigation.10

The available evidence showing the impact of ERAS protocols on GC patients who have undergone gastrectomy is favourable, although the demonstrated benefits vary depending on the study. This may be due to the heterogeneity of the patient profile included in the studies, the extent of the surgery, the approach, the tumour stage, the definition of PO morbidity, the criteria for hospital discharge used and the variable adherence to the different ERAS items. A recent meta-analysis of 18 randomised trials and 1782 patients undergoing gastrectomy for gastric ADC showed reductions in hospital stay, intestinal transit time, pulmonary complications and costs, but no benefit was found in relation to the rate of surgical wound infection or the general rate of PO complications.35 It should be noted that there was a higher percentage of re-admission in the ERAS group, which may be related to the older age of the patients in one of the studies and/or poor compliance with the protocol.35 Regarding patients with locally advanced carcinoma undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy, excluded in most of the studies, a recent study in 114 patients observed a benefit regarding hospital stay and time to tolerance of a semi-liquid diet.36 The results of studies on compliance with ERAS in GC patients are also variable. On the one hand, Jung et al.37 analysed patients with a mean age of 53 years, most of whom with stage I disease, with good functional status and undergoing a minimally invasive approach. The compliance ranges in this context were 88%–100% depending on the item. Regarding nutrition, 95.2% tolerated fluids six hours after surgery and 88.7% were able to start the diet on the first PO day.37 Compliance was lower in those with an open approach and in subjects with higher comorbidity. On the other hand, the Italian study by Fumagalli et al.38 analysed an older population (mean age 73 years), with more advanced disease and a high percentage of laparotomy, where a third of the patients received neoadjuvant therapy. In this scenario, adherence to the protocol was 23%–88%, with a higher rate of complications and re-admissions than in the study by Jung et al. Regarding the onset of PO tolerance, 77% and 70% of the patients tolerated the intake of liquids and solids on the third and fourth day after surgery, respectively.38

Post-surgical nutritional therapyAfter gastrectomy, it is recommended to start oral intake early with clear liquids from 6−8h after the procedure and to progress cautiously and according to tolerance, starting with a liquid diet on the first day after surgery and increasing to a mashed/soft consistency on successive days.22,34,39 It has been shown that early tolerance after GC surgery promotes the early recovery of intestinal transit and a reduction in hospital stay without increasing the rate of complications.40

The ESPEN guidelines recommend the use of oral or enteral immunonutrition in malnourished patients in the context of traditional perioperative care and especially postoperatively.22,31 If EN via a tube is required, there is evidence of a lower rate of complications, hospital stay and costs compared to PN.41 Although intraoperative jejunostomy placement is not routinely advised in GC surgery,4 its performance can be assessed in selected patients for whom poor tolerance is expected early after the procedure (for example, due to high risk of anastomotic leakage).4,22 In such cases, EN via jejunostomy should be started 24h after surgery, potentially using polymeric rather than oligomeric diets.22 Jejunostomy not only allows early PO EN, but it can also help improve nutritional status in the medium term after hospital discharge.22 PN is reserved for those situations, usually derived from PO complications (for example, ileus), where nutrition through the gastrointestinal tract is not possible.22

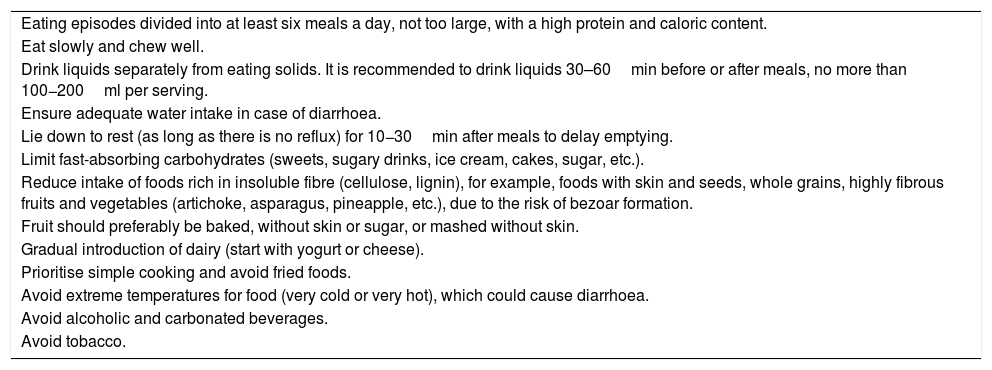

The main nutritional challenges faced by a patient undergoing GC surgery in the medium and long term are those derived from the anatomical and functional modification of the gastrointestinal tract, which fundamentally depends on the volume of gastric resection and the type of transit reconstruction. This has an impact on the intake, tolerance and assimilation of diet and nutrients. The reduction or absence of the gastric reservoir can condition a sensation of early satiety with painful fullness, meteorism, nausea and vomiting, which generally tend to improve progressively over time. The adequacy of the diet plays a fundamental role in adapting to the new situation and seeks to mitigate or avoid weight loss, DS and post-ingestion digestive discomfort (Table 3).42,43

Nutritional recommendations in patients who have undergone gastrectomy.42,43

| Eating episodes divided into at least six meals a day, not too large, with a high protein and caloric content. |

| Eat slowly and chew well. |

| Drink liquids separately from eating solids. It is recommended to drink liquids 30–60min before or after meals, no more than 100−200ml per serving. |

| Ensure adequate water intake in case of diarrhoea. |

| Lie down to rest (as long as there is no reflux) for 10−30min after meals to delay emptying. |

| Limit fast-absorbing carbohydrates (sweets, sugary drinks, ice cream, cakes, sugar, etc.). |

| Reduce intake of foods rich in insoluble fibre (cellulose, lignin), for example, foods with skin and seeds, whole grains, highly fibrous fruits and vegetables (artichoke, asparagus, pineapple, etc.), due to the risk of bezoar formation. |

| Fruit should preferably be baked, without skin or sugar, or mashed without skin. |

| Gradual introduction of dairy (start with yogurt or cheese). |

| Prioritise simple cooking and avoid fried foods. |

| Avoid extreme temperatures for food (very cold or very hot), which could cause diarrhoea. |

| Avoid alcoholic and carbonated beverages. |

| Avoid tobacco. |

“Postgastrectomy syndromes” are those complications that occur later following gastrectomy, resulting from functional and anatomical alterations of the gastrointestinal tract.44 These syndromes can manifest in isolation or more commonly as a combination of several of them, and it is often not easy to discern the role of each one. Each of these clinical situations is described below.

Weight lossPatients undergoing GC gastrectomy experience sustained weight loss during the first year, which stabilises thereafter.19 Cuerda et al. report a 16% weight decrease with no difference between total or partial gastrectomy.45 However, other studies have found greater weight loss in relation to the extent of gastric resection.46 The origin is multifactorial due to anorexia, diarrhoea, restrictive food intake, DS and malabsorption, among others. In patients with nutritional risk, dietary advice together with the use of ONS mitigates weight loss and the incidence of sarcopenia,47 especially after total gastrectomy.46

Dumping syndromeThis is the name given to the set of gastrointestinal and vasomotor manifestations attributed to the rapid passage of hyperosmolar chyme (particularly carbohydrates) to the small intestine.44,48 DS can be described as early or late depending on the clinical signs and symptoms.48 Early DS occurs within the first hour following ingestion and manifests with both gastrointestinal symptoms (fullness, abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhoea) and vasomotor symptoms (diaphoresis, palpitations, flushing).48 Late DS, which is less common and occurs one to three hours following ingestion, causes predominantly vasomotor symptoms due to hypoglycaemia secondary to the insulin spike after the rapid arrival of food in the intestine.48 DS decreases oral intake, which promotes weight loss and has a negative impact on quality of life.48

Mine et al.49 assessed the prevalence of dumping syndrome in 1153 surgical GC patients through a symptom questionnaire. In total, 67.6% manifested at least one symptom of early dumping, most commonly abdominal pain or fullness.49 In contrast, 38.4% manifested at least one symptom of late dumping.49 Comparing surgical techniques, patients undergoing total gastrectomy were the most symptomatic.49

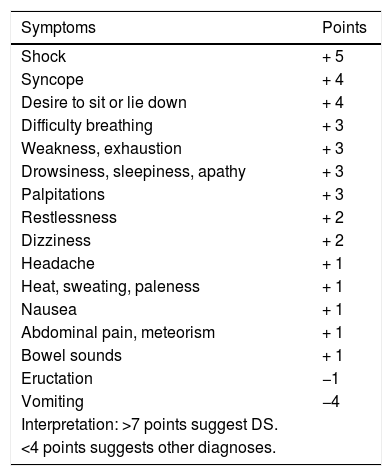

The diagnosis of DS is essentially clinical.44,48 The symptoms-based scoring system developed by Sigstad may be useful (Table 4), according to which a score of more than seven points suggests DS.50 In late DS, capillary blood glucose measurement has poor diagnostic performance, so continuous glucose measurement may be useful.51 The diagnostic test of choice is the oral glucose tolerance test48 in which venous blood glucose, haematocrit, heart rate and blood pressure are measured before, and every 30min up to 180min after the administration of an oral solution containing 75g of glucose.48 An early (30min) 3% increase in haematocrit suggests early DS, while the development of hypoglycaemia at 60−180min suggests late DS.48 An early 10 bpm increase in heart rate is the best predictor of DS.48 The use of the mixed meal tolerance test in late DS has also been suggested, but there is no consensus on this.48

Sigstad scoring system for the diagnosis of dumping syndrome.50

| Symptoms | Points |

|---|---|

| Shock | + 5 |

| Syncope | + 4 |

| Desire to sit or lie down | + 4 |

| Difficulty breathing | + 3 |

| Weakness, exhaustion | + 3 |

| Drowsiness, sleepiness, apathy | + 3 |

| Palpitations | + 3 |

| Restlessness | + 2 |

| Dizziness | + 2 |

| Headache | + 1 |

| Heat, sweating, paleness | + 1 |

| Nausea | + 1 |

| Abdominal pain, meteorism | + 1 |

| Bowel sounds | + 1 |

| Eructation | −1 |

| Vomiting | −4 |

| Interpretation: >7 points suggest DS. | |

| <4 points suggests other diagnoses. |

Taken from Sigstad.50

The initial approach to DS is based on information for the patient and strict adherence to dietary measures (eating small meals frequently, chewing food well, eating a diet rich in protein, avoiding fast-absorbing carbohydrates, drinking fluids separately from eating solids, avoiding alcohol and encouraging lying down 30min after meals).44,48 Soluble fibre (guar gum or pectin) can be used to slow transit, although good tolerance to this measure has generally not been reported.44 Pharmacological treatment is reserved for patients with DS after failure of dietary measures.48 Acarbose (50−100mg before meals), an alpha-glucosidase inhibitor, may be useful as it affects the absorption of carbohydrates and therefore improves the symptoms and incidence of hypoglycaemia in late DS.51 Somatostatin analogues have been shown to be useful in the control of both early and late DS, and can be administered subcutaneously three times a day or intramuscularly every two to four weeks (prolonged-release formulas).48

If ONS are required to treat malnutrition in patients with DS, some experts recommend specific formulas for diabetes52 due to their higher percentage of fats and lower percentage of carbohydrates (which also have a low glycaemic index), choosing those with lower osmolarity43 and in which the fibre content is 100% soluble.

Maldigestion and malabsorptionMaldigestion and malabsorption of nutrients can manifest with a wide clinical spectrum, from the absence of symptoms or the presence of abdominal distension and flatulence, to the appearance of diarrhoea with severe steatorrhoea. The two mechanisms involved and which are potentially treatable are exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI) and bacterial overgrowth (BO).

EPI is common after gastrectomy, affecting up to 75% of patients.53 It has been proposed that the mechanisms by which it occurs are a decrease in pancreatic secretion due to the absence of neural gastric reflexes and pancreatic denervation (in the context of lymphadenectomy and section of the vagus nerve) and, above all, the asynchrony between the arrival of nutrients to the intestine and the secretory response of the pancreas, due to the anatomical alteration.54 In clinical practice, it is common to start empirical treatment with pancreatic enzymes in patients with clinical suspicion.54 Some of the common diagnostic tests, such as the foecal elastase test, may underestimate the presence of EPI in patients who have undergone gastrectomy.54 The triolein-labelled mixed triglyceride breath test (13C) has been proposed as a good alternative after gastrointestinal tract surgery, since the result of expired 13CO2 indicates the efficiency of the digestion process.55 The dose of the enzyme treatment is usually around 50,000 IU of lipase in main meals, requiring adjustment according to the severity of symptoms and the fat content in the diet.54 Efficacy studies of this treatment after gastrectomy offer mixed results, failing to demonstrate a significant improvement in symptoms associated with EPI. However, benefits are seen in terms of reduction of massive steatorrhoea, improvement in the Instant Nutritional Assessment scale (based on albumin and lymphocyte levels), increased prealbumin levels and improved quality of life.53,56

BO is common after gastrectomy, with prevalences of 61%–75%.57,58 The mechanisms underlying its onset are loss of hydrochloric acid and its bactericidal function, gastrointestinal motility disorder and reduction of defensive substances in intestinal secretions.59 Maldigestion and malabsorption of essential nutrients occurs due to the deconjugation of bile acids by bacteria, which prevents the emulsification and absorption of lipids, the deamination of amino acids, which limits their availability as anabolic substrate, and due to the degradation of carbohydrates by bacteria and decreased activity of disaccharidases in damaged intestinal mucosa.59 Clinically, it can be asymptomatic or aggravate postprandial digestive symptoms in patients who have undergone gastrectomy (diarrhoea, pain and abdominal distension).58 The gold standard for its diagnosis is culture of the jejunal aspirate. However, in clinical practice breath tests are used because they are simpler and non-invasive.57,59 Treatment is with antibiotics, including rifaximin, metronidazole or ciprofloxacin.57 Rifaximin is the most studied drug given its limited systemic absorption. However, a study in patients with BO and a history of gastrectomy for cancer or gastrojejunostomy for peptic ulcer found metronidazole to be superior to rifaximin in the improvement of expired H2 and BO clinical signs and symptoms.60 The hypothesis of the authors is that the difficulty in reaching the excluded loop and acquiring a sufficient concentration in it would reduce the action of rifaximin in this context.60

Regarding diet in patients with maldigestion that is adequately treated, in general it is not necessary to restrict fat intake in the diet,61 but it is necessary to avoid high fibre intake due to its potential interference with enzyme therapy.62 There is a theoretical advantage to the use of predigested formulas (with a higher fat intake in the form of medium-chain fatty acids), especially when maldigestion is not controlled despite adequate treatment of EPI and/or BO.

Postvagotomy diarrhoeaVagal denervation causes a type of diarrhoea that is usually episodic, explosive and not always related to oral intake,44 with a tendency to improve and even spontaneous resolution over time.44

Micronutrient deficiencyVitamin B12. After gastrectomy, there is a loss of intrinsic factor secreted by parietal cells, which under normal conditions is responsible for 99% of vitamin B12 absorption in the terminal ileum. Hu et al. studied the evolution of vitamin B12 levels after GC gastrectomy, observing a cumulative rate for vitamin B12 deficiency of 100% in total gastrectomy and 15.7% in partial gastrectomy four years after surgery.63 The median time to deficiency was 15 months after total gastrectomy.63 It has been proposed that the prophylactic supplementation of this vitamin be started routinely after total gastrectomy,39 while for partial gastrectomy, periodic monitoring and early treatment of the deficiency be carried out, taking into account that older patients or those with lower presurgical levels of vitamin B12 are at greater risk of developing this deficiency.63 The recommended dose for patients who have undergone gastrectomy is 1000μg intramuscularly per month, with oral doses of 500−1000μg per day a possible alternative.39

Iron. Iron deficiency is a common finding in GC patients. Its most probable causes are duodenal bypass, gastrointestinal losses and malabsorption due to hypochlorhydria. More than 40% of patients require iron supplements after gastric surgery.45 To treat iron deficiency, 150−300mg/day of iron split into several doses is recommended,39 with intravenous supplementation possibly being necessary in cases of anaemia with intolerance to oral preparations.

Calcium and vitamin D. Cuerda et al. report in their study that 45% of patients who have undergone gastrectomy had low levels of 25-OH vitamin D and 76% had secondary hyperparathyroidism.45 It should be taken into account that plasma calcium levels are usually normal due to the mobilisation of calcium from bone. Although there are no universal recommendations in this regard, some authors recommend prophylactic supplementation with calcium and vitamin D in GC patients who have undergone gastrectomy.39

Other micronutrients such as folic acid, zinc or other fat-soluble vitamins (A, E, K), should be supplemented if their deficiency is detected during follow-up.

AnaemiaThe prevalence of anaemia after gastric resection is around 24%.45,64 It is mainly due to iron and vitamin B12deficiencies, although other deficiencies (such as folic acid) may also play a role in its onset.

Bone diseaseAccording to a meta-analysis, the estimated incidence of osteoporosis after GC gastrectomy is 36%,65 being higher in women and independent of the extent of gastric resection.65 It is mainly attributed to secondary hyperparathyroidism (due to a deficient intake and/or malabsorption of calcium and vitamin D). Therefore, an adequate intake of calcium and/or vitamin D must be guaranteed, as well as periodic monitoring of bone mineral density by densitometry.39

Palliative nutrition in gastric cancer patientsMalnutrition in advanced stages of GC has been shown to have a negative impact on quality of life and survival.66 The Sociedad Española de Oncología Médica [Spanish Society of Medical Oncology] recommends that the nutritional status of patients with advanced cancer be assessed.12

NS must be implemented respecting the principle of autonomy of the patient, weighing the risk-benefit of each intervention and following the principles of proportionality.67 The clinical course of GC can impede oral tolerance and gastrointestinal tract functionality. Malignant gastric obstruction may require bypass surgery, prosthesis placement or ostomy.

Home PN (HPN) has been used in patients with advanced GC who are unable to have EN in the context of intestinal obstruction due to carcinomatosis. In fact, the most common use of HPN in Spain is for palliative cancer patients.68 In their study on the role of HPN in cancer patients with intestinal obstruction and carcinomatosis, Guerra et al.69 show that it is safe and that in those who respond to CT, the additional administration of HPN also improves survival. When considering HPN in a patient with advanced cancer, the following should be taken into account: the patient's wishes, quality of life, functional status (Karnofsky Performance Status greater than 50), social and family support and a life expectancy of more than one to three months.11,70

Nutrition in gastric cancer survivorsGC survivors are a group with potential nutritional risk, so periodic monitoring should not be neglected.12 The high frequency of symptoms that can interfere with their nutrition and quality of life should be taken into account. In this regard, a study by Lin et al.71 identifies the most common symptoms in these patients to be abdominal pain, followed by others such as nausea and vomiting, early satiety, diarrhoea and reflux.

It is generally recommended that an adequate weight and a healthy lifestyle be maintained, which includes being physically active and avoiding toxins such as tobacco and alcohol.10,12 Regarding diet, the general recommendations for cancer survivors are to increase consumption of vegetables, fruits and whole grains, and to avoid saturated fats and red meat.10 In GC patients, additional dietary changes may be necessary according to the specific circumstances of each patient, taking into account comorbidities and symptoms.

ConclusionsA multidisciplinary approach is essential in GC patients, and there is growing evidence of the importance of adequate nutritional support. The complexity and high prevalence of the various nutritional challenges make the participation of specialised nutrition teams essential. Adequate nutritional management has a potentially positive impact on the clinical situation, quality of life and even survival of this group.

FundingThis study has not received any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Carrillo Lozano E, Osés Zárate V, Campos del Portillo R. Manejo nutricional del paciente con cáncer gástrico. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:428–438.