Paraganglioma are uncommon endocrine tumors that arise from extra-adrenal autonomic paraganglia; some cases are able to secrete catecholamines1 and develop metastatic tumor spread.2

The leading cause of hypercalcemia admitted to the hospital is malignancy3; hypercalcemia occurs in about one quarter of patients with cancer, and it is based on 3 main mechanisms, from which PTHrP secretion is the most frequent humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (HHM)].4 In all series, PTHrP secretion has been related to poor outcomes, increased metastatic potential and increased death rates.4,5 HHM in pheochromocytomas was first described in the 1980s, since then, some cases have been reported,6–12 but to the best of our knowledge, only one patient with PTHrP producing paraganglioma has been previously described.13 Furthermore, our case represents a non-catecholamine-secreting abdominal tumor with malignant transformation.

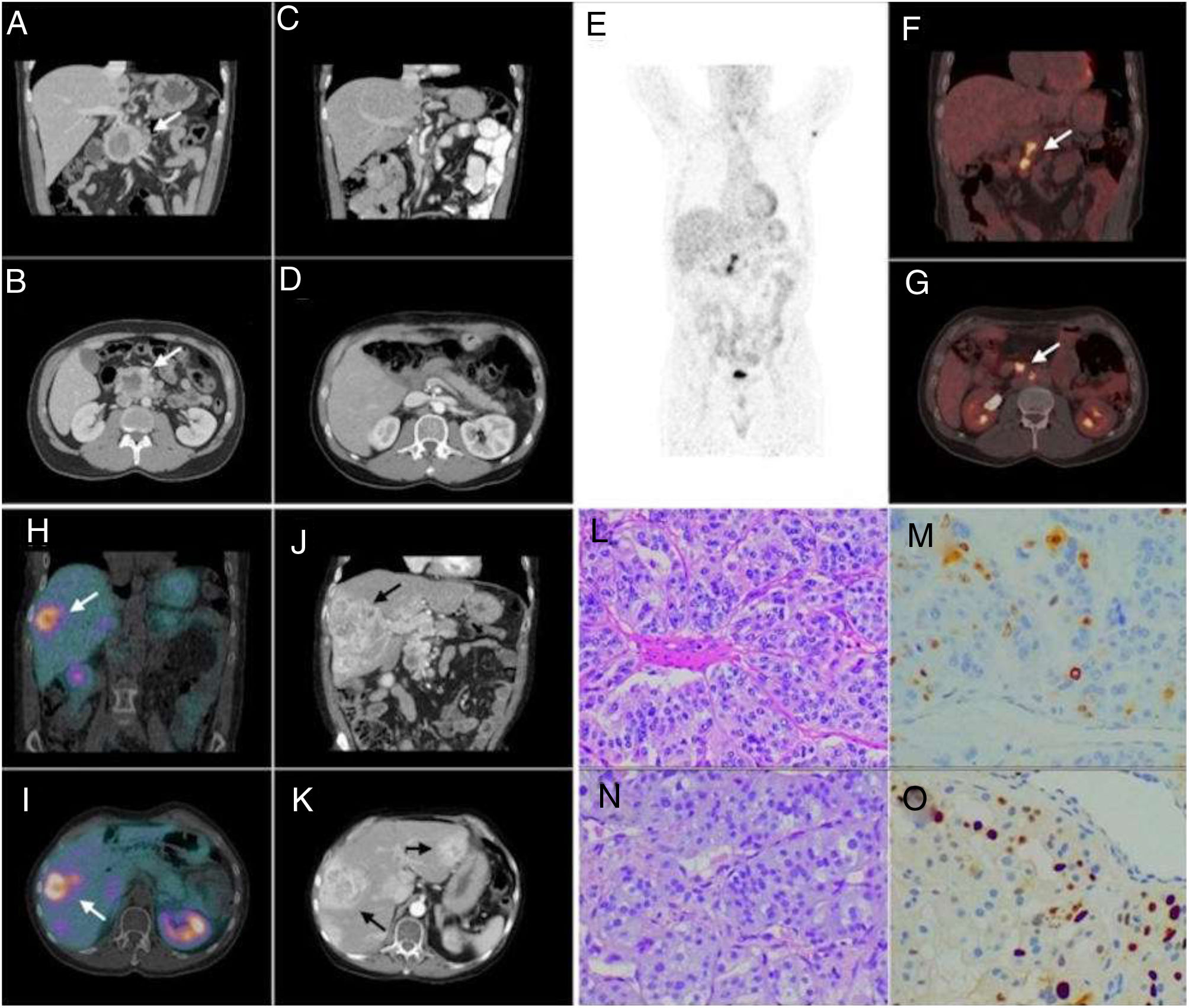

A 61-year-old man was diagnosed with a non-secreting paraganglioma in the head and uncinate process of the pancreas in 2010 due to an acute-onset epigastric abdominal pain. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a 6cm heterogenous mass in the referred area (Fig. 1A, B); he underwent cephalic duodenopancreatectomy nine months later (Fig. 1C, D). The histopathology analysis showed a peripancreatic paraganglioma with extension to the head of the pancreas and superior mesenteric artery. Tumor cells were positive for S100, chromogranin-A and synaptophysin, Ki-67 index was 15–20% (Fig. 1L, M). Follow-up with CT and I123-iodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy (I123-MIBG) scans was performed, later, ganglia (Fig. 1E–G) and then liver metastasis were observed (Fig. 1H, I). A liver biopsy revealed a metastasis of paraganglioma, with a ki67 of 20–30% (Fig. 1N, O). Several chemotherapy schemes were administered with partial response and later progressive disease (Fig. 1J, K). Bone involvement was never evidenced and serum calcium levels were normal since diagnosis. Nine years after the initial diagnosis, the patient was admitted to our service after presenting one week of diarrhea, behavioral disturbance, motor clumsiness, timing disorientation, self-management deficit, verbiage and mood lability. Physical examination showed hypertension without tachycardia, lower limbs swollen, neurological assessment did not show any focal impairment or meningeal signs, and his body weight was stable. At his admission, laboratory examinations showed hypokalemia (2.3mEq/L), hypercalcemia (12.3mg/dL), hypophosphatemia (2mg/dL), and slightly raised liver function enzymes; kidney function, magnesium and pH were normal. Urinary analysis was consistent with extra-renal potassium losses, calcium excretion was increased. ECG showed a sinus rhythm, flattened T waves, inverted in V2 and V3 and non-prolonged QT interval. Later blood tests evidenced normal 1,25-OH-Vitamin D (45pg/mL, normal range (NR): 18–71), low 25-OH vitamin D (5ng/dL, NR: >20), low PTH (12.3pg/mL, NR: 18–88), and increased PTHrP (14pmol/l, NR: <1.5) levels. Serum fractionated metanephrines and cerebral CT scan were normal. Hypercalcemia was firstly treated with hydration, zoledronic acid infusion, furosemide and parenteral steroids, after 1 week, without complete remission but clinical improvement, cinacalcet was added; potassium and phosphate levels were corrected using parenteral supplements. On day 9 of admission he was discharged with normal calcium and potassium serum levels. During the following months, the general status of the patient improved. He did not receive any additional treatment addressed to the tumor. After 3 months he returned to the hospital after seizure and neurological deterioration, he was diagnosed with brain metastases and died one day after. The genetic test performed in the tumor revealed a somatic mutation p.Arg161Gly in the von Hippel Lindau (VHL) gene.

Coronal and axial CT views (A, B) show a 6cm heterogeneous mass in the head and uncinated process of the pancreas, with a necrotic cystic component and intense peripheral enhancement suggesting hypervascular behavior. Coronal and axial postoperative CT views (C, D) of the pancreatic mass: after surgery, complete resection was achieved. Maximum intensity projection, coronal and axial [18F] FDG PET/CT images (E–G), performed five years after the pancreatic surgery, show a hypermetabolic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy in the region of the surgical bed (SUVmax: 6.9), suggestive of tumor recurrence. Coronal and axial [99mTC] octreotride SPECT/CT images (H, I) performed 3 years after the local recurrence, show expression of somatostatin receptors in the hepatic lesions and in the previously known retroperitoneal adenopathies. Coronal and axial last control CT views (J, K) showed enlargement of known liver lesions and appearance of new liver lesions; these findings were compatible with progressive disease. Hematoxylin eosin stain of the primary tumor (20×) reveals well-defined nests of cuboidal cells (Zellballen) separated by intensely vascularized fibrous septa; cells have moderately abundant, basophilic and granular cytoplasm (L), Ki67 index was 15–20% (M). The liver biopsy (N) was compatible with metastasis of paraganglioma; Ki67 index was 20–30% (O).

Paraganglioma are uncommon endocrine tumors with increasing prevalence and diagnosis due to better diagnostic procedures and genetic testing for familial forms. They arise from of extra-adrenal autonomic paraganglia, however, non all of them are diagnosed as catecholamine-secreting tumors.1 Parasympathetic and sympathetic paragangliomas differ not only in their anatomic distribution, but also in their association with underlying genetic syndromes and clinical features. Typically, non-functional paragangliomas arise in non-chromaffin cells from parasympathetic ganglia located along the glossopharyngeal and vagal nerves in the neck and the base of the skull; in contrast, functional-paragangliomas originate from sympathetic ganglia, usually have excess catecholamine secretion (especially norepinephrine) and are located predominantly in the abdomen or, secondly, in the thorax.3 Most paragangliomas in adults appear to be sporadic, but genetic screening guided by clinical presentation is recommended. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDHx) germline mutations, VHL disease, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and neurofibromatosis type 1, are the most frequent associated conditions, and are related to worse prognosis in some cases.14

The majority of paragangliomas are considered as benign tumors, however, a fraction shows metastatic behavior. Unfortunately, the only absolute criteria of malignancy is evidence of metastatic tumor spread; in this context, location, size, PASS score, S100 immunoreactivity and Ki67 labeling index should be evaluated for predicting risk of malignancy.2

In order to study the relation between PTHrP secretion and paragangliomas, we matched various terms in the PubMed database. Only one case of PTHrP-secreting paraganglioma13 and seven cases of PTHrP-secreting pheochromocytomas6–12 have been previously described. All reported pheochromocytomas were benign catecholamine-secreting tumors, in which PTHrP hypersecretion resolved after surgery. In contrast, the reported paraganglioma, as well as our case, was an abdominal, non-functioning, metastatic tumor in a male patient,13 but some differences between both cases are notable, the previously described case occurred in a young male, who presented with PTHrP induced hypercalcemia and bone metastasis since the diagnosis; additionally, in this case, tumor debulking induced calcium normalization after one month. Our case would be the second report of PTHrP secreting paraganglioma and the first one managed with medical treatment for controlling hypercalcemia; furthermore, it represents a non-catecholamine-secreting abdominal tumor with subsequent dedifferentiation.

This clinical case reveals the importance of close and long-term follow-up in patients with pheochromocytomas and/or paragangliomas independently of the genetic test, especially if Ki67 is elevated, or if lymph node metastases are present at the diagnosis, since these tumors may develop metastasis and present with PTHrP secretion, which represents a sign of bad prognosis.

FundingJuan Rodés, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (JR19/00050).

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

![Coronal and axial CT views (A, B) show a 6cm heterogeneous mass in the head and uncinated process of the pancreas, with a necrotic cystic component and intense peripheral enhancement suggesting hypervascular behavior. Coronal and axial postoperative CT views (C, D) of the pancreatic mass: after surgery, complete resection was achieved. Maximum intensity projection, coronal and axial [18F] FDG PET/CT images (E–G), performed five years after the pancreatic surgery, show a hypermetabolic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy in the region of the surgical bed (SUVmax: 6.9), suggestive of tumor recurrence. Coronal and axial [99mTC] octreotride SPECT/CT images (H, I) performed 3 years after the local recurrence, show expression of somatostatin receptors in the hepatic lesions and in the previously known retroperitoneal adenopathies. Coronal and axial last control CT views (J, K) showed enlargement of known liver lesions and appearance of new liver lesions; these findings were compatible with progressive disease. Hematoxylin eosin stain of the primary tumor (20×) reveals well-defined nests of cuboidal cells (Zellballen) separated by intensely vascularized fibrous septa; cells have moderately abundant, basophilic and granular cytoplasm (L), Ki67 index was 15–20% (M). The liver biopsy (N) was compatible with metastasis of paraganglioma; Ki67 index was 20–30% (O). Coronal and axial CT views (A, B) show a 6cm heterogeneous mass in the head and uncinated process of the pancreas, with a necrotic cystic component and intense peripheral enhancement suggesting hypervascular behavior. Coronal and axial postoperative CT views (C, D) of the pancreatic mass: after surgery, complete resection was achieved. Maximum intensity projection, coronal and axial [18F] FDG PET/CT images (E–G), performed five years after the pancreatic surgery, show a hypermetabolic retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy in the region of the surgical bed (SUVmax: 6.9), suggestive of tumor recurrence. Coronal and axial [99mTC] octreotride SPECT/CT images (H, I) performed 3 years after the local recurrence, show expression of somatostatin receptors in the hepatic lesions and in the previously known retroperitoneal adenopathies. Coronal and axial last control CT views (J, K) showed enlargement of known liver lesions and appearance of new liver lesions; these findings were compatible with progressive disease. Hematoxylin eosin stain of the primary tumor (20×) reveals well-defined nests of cuboidal cells (Zellballen) separated by intensely vascularized fibrous septa; cells have moderately abundant, basophilic and granular cytoplasm (L), Ki67 index was 15–20% (M). The liver biopsy (N) was compatible with metastasis of paraganglioma; Ki67 index was 20–30% (O).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/25300180/0000006900000001/v1_202202280604/S2530018022000075/v1_202202280604/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)