Visual disturbances and hypopituitarism are not exclusive symptoms of pituitary macroadenomas. Other tumors clinically behaving as macroadenomas may occur in the sellar area. The most common of such tumors include craniopharyngioma, Rathke pouch cyst, and meningioma.1 The case of a female patient in whom a pituitary macroadenoma was initially suspected but who was finally diagnosed with another sellar tumor is reported below.

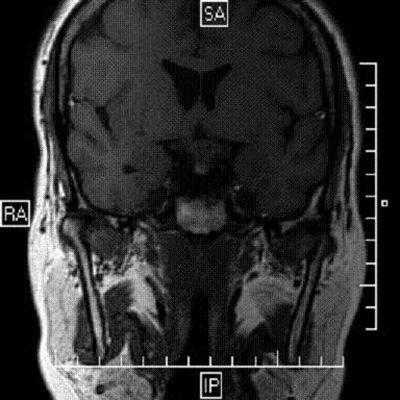

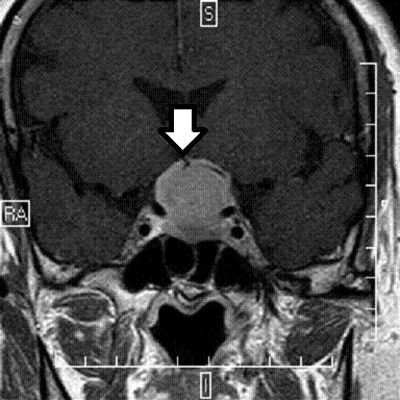

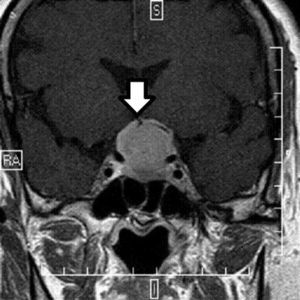

This was a 49-year-old female patient born in the Philippines with a history of hypertriglyceridemia treated with gemfibrozil 900mg/day and high blood pressure treated with indapamide 2.5mg/day. She was referred to our clinic by her primary care physician for an impaired thyroid function in two consecutive laboratory tests showing decrease free tetraiodothyronine (T4) levels and normal thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels (first laboratory tests: TSH 3.26μIU/mL and free T4 0.50ng/mL; second laboratory tests: TSH 2.74μIU/mL and free T4 0.60ng/mL; normal ranges were 0.465–4.68μIU/mL for TSH and 0.78–2.19ng/dL for free T4 respectively). Patient reported a self-limited episode of galactorrhea and mastodynia 8 years before. She had been examined in her country, but had no medical reports, and stated that no cause had been found. In the past 2 years, the patient had experienced very severe asthenia, facial edema, and amenorrhea. She was also being monitored at the ophthalmology department for decreased visual acuity. A computed campimetry performed revealed bitermporal hemianopsia, and the ophthalmologist had therefore requested magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) which had not been performed yet. Facial edema, particularly of the eyelids, was conspicuous. The thyroid gland could be palpated, but no nodules were felt. There were no other remarkable findings in the physical examination or galactorrhea. A pituitary macroadenoma was suspected, and repeat measurements of pituitary basal hormones and assessment of MRI were therefore decided. MRI of the brain (Fig. 1) showed a lesion with its center in the pituitary gland with a significant suprasellar component that appeared homogeneously hypointense in T1 and T2 with no presence of calcium foci, necrosis, or hemorrhage. The lesion was 25×24×26mm in diameter, showed no signs of invasion of cerebral parenchyma, and did not invade sphenoidal sinus. The lesion extended laterally encompassing completely the left internal carotid and supraclinoid arteries, and partially the right internal carotid artery, which had a normal size with a signal void, which suggested patency. The chiasm was not adequately visualized, which was considered to be due to chiasm invasion. However, sections were too thick for adequate definition of this structure. Laboratory tests showed, in addition to pituitary hypothyroidism, hypopituitarism of the somatotropic and gonadotropic axes, as well as moderate hyperprolactinemia: follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) 3.62mIU/mL (normal range (NR), 21.5–131), luteinizing hormone (LH) 0.44mIU/mL (NR: 13.1–86.5), 17-beta-estradiol 9.48pg/mL (NR: 5.3–38.4), prolactin: 53.90ng/mL and 59.50ng/mL in the first and second samples respectively (NR: 3–25), growth hormone (GH) <0.05ng/mL (NR <8.6), adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) 49.90pg/mL (NR: 4.7–48.8), cortisol 18.80mg/dL (NR: 5–25) and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) 81.45ng/mL (NR: 90–360). Treatment was started with levothyroxine 25μg daily for 2 weeks and 50μg thereafter. Although the tumor was initially considered to be a macroadenoma, suprasellar extension suggested that it could be a meningioma, and repeat MRI was performed, but this time focused on the pituitary gland and using sections less than 3-mm thick. MRI (Fig. 2) revealed persistence of a lesion centered in the pituitary gland with a significant suprasellar component, homogeneously hypointense in T1 and T2 with no apparent calcium foci, necrosis, or hemorrhage. The lesion extended laterally encompassing completely the left internal carotid and supraclinoid arteries, and partially the right internal carotid artery. Optic chiasm was cranially reflected, with a slight deformity in third ventricle floor. Anteriorly, lesion extended toward the sphenoidal plane at an obtuse angle. After contrast administration, a small dural tail was associated (arrow in Fig. 2). Posteriorly, the lesion reached the prepontine cistern with no brain stem deformity. T1 hypersignal of the neurohypophysis was seen, adjacent to which there was a slightly more intense contrast enhancement that appeared to correspond to the compressed adenohypophysis. The pituitary stalk was not clearly identified. Signal homogeneity and extension to the sphenoidal plane and presence of dural tail suggested meningioma of sellar diaphragm as first diagnostic possibility.

Patient underwent surgery consisting of bifrontal craniotomy. Wide tumor excision was performed, completely decompressing the optic chiasm and leaving residual tumor fully encompassing the anterior communicating artery and both anterior cerebral arteries. Histological report confirmed suspicion of meningothelial meningioma, describing psammoma bodies, a fibrohyaline reaction, and absence of architectural changes, cytological atypia, and mitotic activity.

Preoperative temporal hemianopsia of the right eye persisted after surgery, and patient additionally experienced amaurosis in her left eye, although in the last visits she was already able to see light through this eye. She had partial central diabetes insipidus, which was controlled with oral desmopressin 0.1mg and persisted in subsequent visits. Control laboratory tests showed, in addition to the abovementioned deficits and hyperprolactinemia, decreased basal cortisol levels and inappropriately normal ACTH levels: FSH 2.12mIU/mL, LH <0.216mIU/mL, prolactin 69.60ng/mL, ACTH 13.82pg/mL and basal cortisol 0.29μg/dL, TSH <0.015μIU/mL, and free T4 1.18ng/dL.

Meningiomas are the most common benign tumors in central nervous system. They arise from arachnoid meningeal cells and may occur in any location of the CNS. Sellar diaphragm is a fold that is perforated for passage of sella turcica. This fold extends over the sellar tubercle to the top of dorsum sellae and clinoid process. Meningiomas arising from this dura mater area grow toward the sella turcica, occupying it and mimicking a pituitary adenoma.2 The concept of meningioma of sellar diaphragm is relatively recent. In their 1938 monograph «Meningiomas», Cushing and Eisenhardt reported meningiomas with these characteristics, but classified them as suprasellar meningiomas. In 1954, Bush and Mahneke reported 25 patients who had undergone surgery for meningioma of sellar diaphragm.3 Finally, in 1995 Kinjo et al.4 proposed that these tumors are classified as type A when they arise from the upper leaf of sellar diaphragm and grow centrally to the sella turcica; as type B when they arise from the same but grow dorsally; and as type C when they are derived from the lower leaf and grow toward the sella turcica. The latter are the ones that clinically behave as pituitary macroadenomas.

Differential diagnosis between pituitary macroadenoma and meningioma of sellar diaphragm is very important because the surgical approach is completely different. Current advances in MRI facilitate distinction, but careful inspection of images is required in cases such as the one reported. Cappabianca et al.5 reviewed MRI images from patients who had been diagnosed with non-functioning macroadenoma when they actually had meningioma of sellar diaphragm. Pituitary gland was always clearly visualized in meningiomas, which showed a bright, homogeneous enhancement after contrast administration, while a poor, heterogeneous enhancement was seen in macroadenomas. The center of the lesion was suprasellar in meningiomas and sellar in macroadenomas. Macroadenomas enlarged the sella turcica. However, meningiomas moderately enlarged sella turcica proportionately to their size. Finally, sellar diaphragm and pituitary stalk were identified in most patients with meningioma.

Meningiomas of sellar diaphragm should be included in differential diagnosis in patients with hypopituitarism and visual disturbances. Their preoperative identification is particularly important because surgical approach will vary.

Please cite this article as: Aragón Valera C, et al. Tumor inesperado en la silla turca. Endocrinol Nutr. 2011;58:370–9.