In recent years, there has been growing interest in diet low in FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) as an important mainstay in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This model of diet was developed by a multidisciplinary team from the Monash University in Melbourne and became well-known after the publication of a study in 2008 showing that dietary FODMAPs acted as causing factors in patients with IBS. Since then there have been several randomized controlled trials which, although with small sample sizes, have again shown the benefits of this dietary pattern.

En los últimos años está creciendo el interés en la dieta pobre en fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) como pilar importante en el tratamiento del síndrome de intestino irritable (SII). Este modelo de dieta lo desarrolló un equipo multidisciplinar de la Universidad de Monash, en Melbourne, y empezó a ganar notoriedad a partir de la publicación de un estudio en 2008 que demostraba que los hidratos de carbono fermentables (FODMAP) de la dieta actuaban como causantes de síntomas en los pacientes con SII. Desde entonces se han llevado a cabo varios ensayos controlados aleatorizados que, aunque con muestras reducidas de pacientes, han vuelto a demostrar las ventajas de este modelo dietético.

In Spain, intestinal bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 2.3–12% of the population, and is more common in females and patients under 55 years of age.1 IBS is the most common cause of consultation in primary care for abdominal pain. The pathophysiology of IBS is unknown, and involves many things, from bowel motility changes to impaired peripheral perception and central processing of nociception in the gastrointestinal tract, known as “visceral hypersensitivity”.2 IBS is defined, using Rome III criteria, as consisting of pain or abdominal discomfort associated with two or more of the following criteria: (a) symptom improvement with defecation; (b) a change in stool frequency; or (c) a change in stool characteristics. These symptoms should have been present at least two days per week during the previous 3 months, and should have started at least 6 months before. There are four subtypes of IBS depending on the predominant symptoms: (a) constipation subtype; (b) diarrhea subtype; (c) alternating subtype; and (d) indeterminate subtype.3 The complex and unknown pathogenesis and the differences between the patients who meet Rome III criteria make it difficult to develop effective strategies for treating IBS.

Sixty-percent of patients associate the intake of some food to symptom occurrence or exacerbation. Clinical signs and symptoms occur within 15min–3h of intake in 28–93% of patients respectively. The food items involved may trigger symptoms by different mechanisms (the activation of mast cells and mechanoreceptors, enzyme deficiencies, impaired bowel motility, abdominal distention, or chemosensitive activation by bioactive molecules). The restriction of some foods (gluten, fiber, fructose, lactose, caffeine, amines, fructose, sorbitol, etc.) has traditionally been used in IBS management. Food is not the cause of the disease, however, but the factor that triggers the symptoms.

FODMAP intake dose-dependently induces symptoms in patients with IBS. These symptoms are more marked when foods are taken together.4,5 Research on the subject suggests that up to 70% of patients who follow a low FODMAP diet experience a significant improvement in symptoms, particularly those related to abdominal pain and distention.6–13 The symptom showing the least improvement is constipation, which may be related to the low fiber provision in this dietary model.

The Low FODMAP diet was included in the guidelines for the treatment of IBS of the British Dietetic Association in 2010,14 and in 2011 in the Australian guidelines.15 Spanish gastroenterologists use drugs (antispasmodics, antidiarrheal, fiber, laxatives, anxiolytics) more frequently than dietary measures for the treatment of the main symptoms,16 despite the fact that dietary changes are the measure most commonly used by patients for symptom self-management.17 The most recent Spanish guidelines for the clinical management of this disease date back to 2005, and do not refer to this novel dietetic approach.18

This article will examine the concept of FODMAPs and their presence in various foods, and explain how to prepare a dietary plan.

General characteristicsFODMAPs have a number of important, unique characteristics with regard to the genesis of symptoms in IBS:

- •

They are only absorbed with difficulty in the small bowel. Fructose (a monosaccharide present in fruit), for example, is absorbed at half the speed of glucose; lactose (a disaccharide found in dairy products) must first be hydrolyzed to glucose and galactose, and many people suffer from a lactase deficiency; non-digestible oligosaccharides, such as fructans and galactans (mainly found in vegetables), usually accumulate in the distal small bowel and the proximal large bowel, thus becoming susceptible to metabolization by intestinal flora.

- •

They are osmotically active. When present in the intestinal lumen, they stimulate the mobilization of a large amount of water, which alters normal intestinal peristalsis, causing abdominal distention and pain and stools of decreased consistency.19

- •

They are rapidly fermentable. They are often an ideal substrate for normal and pathological intestinal flora. The product of this fermentation is gas, which causes distention and the activation of some nociceptive pathways.13

The FODMAP acronym was devised by an Australian group in 2001 to refer to fermentable, short-chain carbohydrates that cause gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects with visceral hypersensitivity.20 This food group includes:

- -

Oligosaccharides: fructans and galactans. These cannot be digested by intestinal enzymes; they are always fermented by intestinal bacteria.

- •

Fructans: these are fructose polymers with a glucose molecule at their end. Fructans with a degree of polymerization of 2–10 are commonly called fructooligosaccharides (FOS). FOS, especially as inulin, are frequently added to foods such as beverages, sauces, and energy bars to increase the fiber content and to act as prebiotics. They may also be present in laxatives or enteral nutrition products.21

FOS is found in some vegetables (artichoke, asparagus, green peas, onion, garlic, leek, Brussels sprouts, beet, chicory, broccoli, cabbage, fennel), pulses (green peas, lentils, chickpeas), nuts (pistachio), and fruit (peach, watermelon, khaki, and custard apple). One of the main dietary sources of fructans is wheat, which is present in many food items including biscuits, bread, breakfast cereals, pasta, couscous, and many bakery products. Rye and barley are also cereals rich in fructans.

- •

Galactans: these are galactose polymers. Their main dietary sources include some pulses such as beans, chickpeas and soybean products, Brussels sprouts, nuts, and cabbage. These foods are frequently included in vegetarian diets, and also in Indian and Mexican cuisine.

- •

- -

Disaccharides (lactose): these consist of glucose and galactose, present in mammalian milk. Lactase is the enzyme metabolizing lactose, and its levels depend on genetic and ethnic factors, or on gastrointestinal conditions. Symptoms associated with lactose malabsorption occur with an intake higher than 7g. The main dietary sources of lactose include milk, yoghurt, ice cream, custard, and soft cheese. Lactase supplements may be used to manage lactose intolerance.

- -

Monosaccharide (fructose): these occur naturally in fruit, vegetables, honey, and as an additive in foods labeled as “diet” or “light”, beverages, and nectars. The intake of this monosaccharide has markedly increased in recent years, especially in the form of “high fructose corn syrup” (HFCS), which has become an increasingly used, low-cost sweetener in a wide range of processed foods. The consumption of carbonated beverages has significantly increased in developed and developing countries, implying a high fructose consumption associated with harmful effects on health (liver steatosis, impaired insulin sensitivity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, or fructose malabsorption with associated gastrointestinal symptoms).22

Fructose absorption occurs in the small bowel, specifically in the apical membrane of enterocytes, where glucose transporter 5 (GLUT5), the only specific fructose transporter, is located. GLUT5 transports fructose passively from the lumen to the blood. Another low-affinity fructose transporter, GLUT2, is also able to recognize other monosaccharides such as glucose and galactose. Fructose is absorbed more slowly than glucose, but is taken up and metabolized faster by the liver. Fructose absorption increases in the presence of glucose, galactose, and some amino acids, and decreases in the presence of sorbitol. GLUT5 is more widely distributed in the proximal bowel (the duodenum and proximal jejunum), and its gene expression appears to be strictly regulated by factors such as nutrition, hormones, and circadian cycles.

Fructose absorption in the small bowel is limited; half the population cannot absorb a load greater than 25g. The physiological consequences of fructose malabsorption include an increased luminal osmotic load, which is a substrate for rapid fermentation by colonic bacteria, impairing gastrointestinal motility and inducing change in intestinal flora. In patients with fructose intolerance, xylose isomerase supplements may be used.

The main foods with high fructose contents are: apple, cherry, mango, pear, watermelon, asparagus, artichoke, honey, and HFCS.

- -

Polyols: Alcohols derived from sugar (sorbitol, mannitol, maltitol, xylitol, isomaltose). These occur in many processed foods, including sweets, chewing gum, ice cream, pastry, bakery products, and chocolate. They may also be found in toothpaste and mouthwashes.

Polyols are only partially digested and absorbed in the small bowel and reach the large bowel, where they are fermented by bacteria. At least 70% of polyols are not absorbed in healthy subjects. Excess polyols (e.g. an amount greater than 50g of sorbitol daily or greater than 20g of mannitol daily) may cause diarrhea and abdominal discomfort.

Sorbitol occurs in fruit (apple, apricot, avocado, blackberry, cherry, nectarine, pear, prune, raisins), and mannitol in vegetables (cauliflower, mushrooms).

The intake of FODMAPs varies from region to region. In North America and Europe, FODMAPs are mainly consumed as fructose and fructans. In the past four decades, the consumption of sugary drinks has increased and currently accounts for 22% of total calorie provision. The intake of pasta and pizza, essential sources of fructans because of their stability and palatability, has also increased. No data are available on the consumption of polyols, but we suspect that their intake in the form of additives in different diet products has also increased.

The diagnosis of the malabsorption of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyolsThe prevalence of fructose and lactose malabsorption in patients with IBS is 45% and 25% respectively.23 In patients in whom a breath test shows adequate fructose and lactose absorption, the restriction of these nutrients is not required. Polyol intake restriction is advisable in all cases.

It should be noted that no breath test is available for two of the main FODMAPs (fructans and glucans). In addition, false positive breath tests may occur in patients with bacterial overgrowth or altered bowel motility and transit rate, all of which usually occur in patients with IBS.

How to prepare a dietary planThe dietary models established to date for IBS management were based on the elimination of some foods. This new model is based on the global, simultaneous reduction of FODMAPs, all fermentable short-chain carbohydrates that may cause similar gastrointestinal symptoms. The symptoms vary depending on the sensitivity of each individual. Symptom improvement is significant after seven days of compliance with the diet, particularly in patients with prior fructose malabsorption.

The Monash University team developed a 297-item food frequency questionnaire (the Comprehensive Nutrition Assessment Questionnaire) to analyze the consumption of macronutrients and micronutrients, and FODMAPs. It also analyzes the glycemic index, as this could be useful both prior to the diet being started upon (to assess and verify whether evolution differs, depending on the prior intake of FODMAPs) and at the end of the elimination phase to verify adherence.24 The team has also developed a smartphone application that may be very helpful for patients.25

It is recommended that this dietary model be maintained for 6–8 weeks, with a subsequent, non-summatory reintroduction of foods removed by groups of different FODMAPs to avoid an additive effect and in order to identify individual tolerance for each group. The aim is that, in the long term, patients will be able to control their symptoms by taking foods that contain FODMAPs according to their tolerance limits.

This dietary model does not include gluten restriction, which is only indicated for patients with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten intolerance.

Thus, a low FODMAP diet restricts the consumption of fructose, fructooligosaccharides and galactooligosaccharides, lactose, and polyols.

In practice, the avoidance of these components implies the avoidance of the following foods with a high FODMAP content:

- •

Cereals such as wheat and derivatives, rye, and barley.

- •

Fruits such as apple, pear, watermelon, peach, cherry, blackberry, nectarine, or mango.

- •

Vegetables such as chicory, onion, garlic, artichoke, asparagus, beet, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, leek, cauliflower, or mushrooms.

- •

Pulses in general: green peas, lentils, beans, soybeans, and chickpeas.

- •

Dairy products: milk and milk products are to be avoided, and replaced by lactose-free dairy products. Calcium-enriched vegetable drinks may also be consumed as a substitute.

- •

Honey.

- •

Artificial sweeteners containing sorbitol (E420), mannitol (E421), isomaltose (E953), maltitol (E965), and xylitol (E967).

General recommendations to be given to patients:

- -

Patients should be advised to keep a diet diary, in which they write down all that they eat and both the frequency and severity of the symptoms they experience during the day (abdominal pain, gas, abdominal distention, stool number and characteristics). The Bristol chart can be recommended for reporting stool appearance, and the Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System for quantifying changes in symptoms over time.26,27

- -

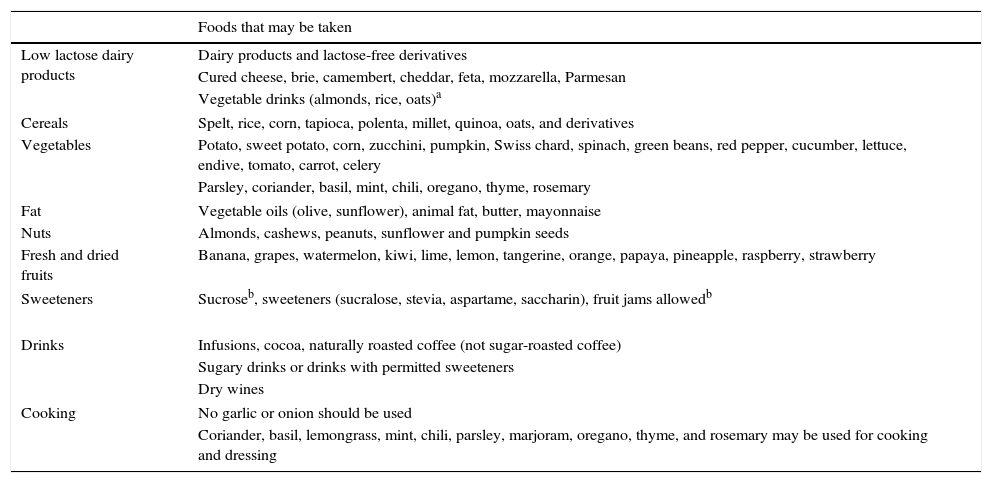

Patients should be reminded that not everybody is the same, and that there will be foods that some of them tolerate well but which others do not. This is why it is important for them to keep a diet diary (Table 1).

Table 1.Foods for preparing a low FODMAP diet (removal phase).

Foods that may be taken Low lactose dairy products Dairy products and lactose-free derivatives Cured cheese, brie, camembert, cheddar, feta, mozzarella, Parmesan Vegetable drinks (almonds, rice, oats)a Cereals Spelt, rice, corn, tapioca, polenta, millet, quinoa, oats, and derivatives Vegetables Potato, sweet potato, corn, zucchini, pumpkin, Swiss chard, spinach, green beans, red pepper, cucumber, lettuce, endive, tomato, carrot, celery Parsley, coriander, basil, mint, chili, oregano, thyme, rosemary Fat Vegetable oils (olive, sunflower), animal fat, butter, mayonnaise Nuts Almonds, cashews, peanuts, sunflower and pumpkin seeds Fresh and dried fruits Banana, grapes, watermelon, kiwi, lime, lemon, tangerine, orange, papaya, pineapple, raspberry, strawberry Sweeteners Sucroseb, sweeteners (sucralose, stevia, aspartame, saccharin), fruit jams allowedb Drinks Infusions, cocoa, naturally roasted coffee (not sugar-roasted coffee) Sugary drinks or drinks with permitted sweeteners Dry wines Cooking No garlic or onion should be used Coriander, basil, lemongrass, mint, chili, parsley, marjoram, oregano, thyme, and rosemary may be used for cooking and dressing - -

People who require special nutritional care (children, pregnant women, people with chronic diseases) should only follow this diet under the supervision of a nutritionist/dietician experienced in therapeutic diets, as a very restrictive diet risks being nutritionally inadequate.

- -

Patients should always take into consideration not only the list of restricted foods, but also the options proposed for replacing such foods, so that they maintain a varied diet.

- -

They should ask their doctor about the need for vitamin supplements if they do not take 2–3 dairy products and 5 servings of vegetables or fruit every day.

- -

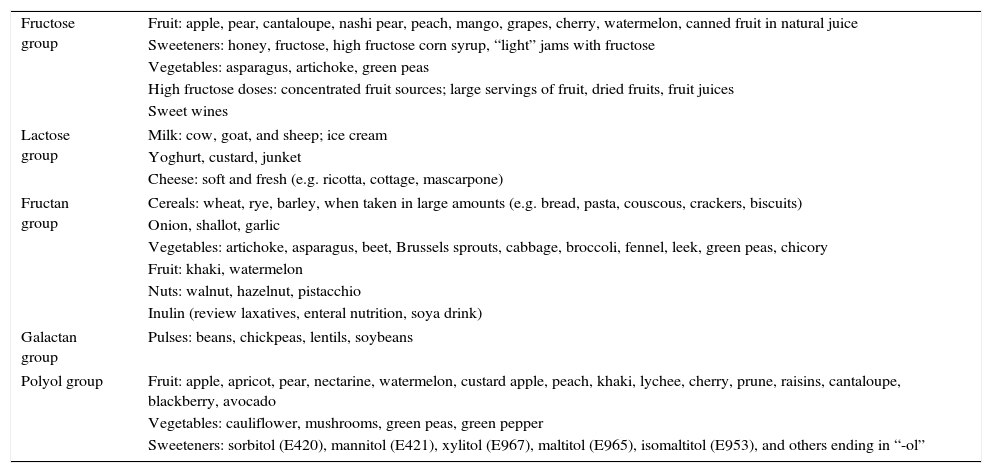

When patients are in the phase of the low FODMAP diet, they should pay careful attention to the labels of packaged foods and drugs to ensure that they do not contain any of the ingredients listed in Table 2.

Table 2.Food with a high FODMAP content (reintroduction phase).

Fructose group Fruit: apple, pear, cantaloupe, nashi pear, peach, mango, grapes, cherry, watermelon, canned fruit in natural juice Sweeteners: honey, fructose, high fructose corn syrup, “light” jams with fructose Vegetables: asparagus, artichoke, green peas High fructose doses: concentrated fruit sources; large servings of fruit, dried fruits, fruit juices Sweet wines Lactose group Milk: cow, goat, and sheep; ice cream Yoghurt, custard, junket Cheese: soft and fresh (e.g. ricotta, cottage, mascarpone) Fructan group Cereals: wheat, rye, barley, when taken in large amounts (e.g. bread, pasta, couscous, crackers, biscuits) Onion, shallot, garlic Vegetables: artichoke, asparagus, beet, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, broccoli, fennel, leek, green peas, chicory Fruit: khaki, watermelon Nuts: walnut, hazelnut, pistacchio Inulin (review laxatives, enteral nutrition, soya drink) Galactan group Pulses: beans, chickpeas, lentils, soybeans Polyol group Fruit: apple, apricot, pear, nectarine, watermelon, custard apple, peach, khaki, lychee, cherry, prune, raisins, cantaloupe, blackberry, avocado Vegetables: cauliflower, mushrooms, green peas, green pepper Sweeteners: sorbitol (E420), mannitol (E421), xylitol (E967), maltitol (E965), isomaltitol (E953), and others ending in “-ol” - -

They should avoid the use of laxatives. If they do take laxatives, they should consult their doctor because some of them may contain FODMAPs, such as inulin.

- -

If they take a nutritional supplement or an enteral nutrition product, they should verify that it does not contain FOS/inulin. If in doubt, they should ask their doctor/nutritionist to assess the possibility of its replacement by another type.

- -

They should be informed that the intake of animal protein (meat, fish, eggs) is not restricted in this type of diet.

Phases of the diet:

- -

Phase 1: removal, a low FODMAP diet for 6–8 weeks. A diet is considered to be low in FODMAPs if it provides less than 0.5g by intake or less than 3g/day (the Australian diet contains on average 23.7g of FODMAPs/day).28 No studies on the usual intake of FODMAPs or detailed tables of the composition of foods in relation to these nutrients are currently available in Spain.

The foods detailed in Table 1 should be taken into account when the diet is being devised.

- -

Phase 2: the reintroduction of foods previously removed, once the phase 1 stage has been completed. The progressive, non-summatory reintroduction of foods by groups, as detailed in Table 2, is advised. For example, only high fructose foods should be reintroduced in the first week, only high lactose foods in the second week (excluding the high fructose foods tested in the first week), only high fructan foods in the third week, and so on.

If symptoms recur after the reintroduction of one of the groups, that group should be once more removed and the process should continue with the next group. It is recommended that a close watch be kept for the occurrence of any symptoms associated with the reintroduction of any given foods in order to evaluate whether these foods should be permanently removed from the diet.

- -

Phase 3: the patients may control their symptoms in the long term, taking foods that contain FODMAPs as tolerated.

One of the main advantages of a low FODMAP diet is the possibility of allowing patients to achieve long-term control of their own bowel symptoms, and the resultant decrease in drug use.

Barriers and negative effectsAdequate diet education provided by qualified professionals is essential for achieving a good adherence to this dietary plan. Prospective studies have reported that 66% of participants considered this dietary plan easy to follow.29

Long-term studies are needed to support the safety of this diet model. Excessively restrictive regimens may be nutritionally deficient. By definition, a number of foods that may be replaced by others with similar properties within each food group (fruits, vegetables, etc.) have usually already been removed from the diet. Pulses, rich in fructans and glucans, are the group for which it is most difficult to find replacement foods. In cases where the permitted intake of fruit, vegetables, and dairy products does not meet nutritional requirements, supplementation with vitamins and minerals should be considered.

A low fiber intake, with its associated prebiotic effect, may have a negative effect that should be taken into account.6 The clinical significance of changes occurring in microbiota while this diet is being followed has yet to be elucidated.30 In this regard, concomitant treatment with probiotics could be given.

Something that is fundamental for the preparation of dietary plans and other materials and that may be helpful for patients (along with apps, recipe books, etc.) is the availability of food tables for each country containing the composition of the most commonly used foods, including detailed, updated data on FODMAP contents. Differences in species, type of culture, etc. may mean that a diet plan proposed in one country may not be totally appropriate in another.

Other indications for diets low in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyolsThe effect of low FODMAP diets has been studied in recent years in other conditions such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, depressive syndrome,31 chronic fatigue, and fibromyalgia. Preliminary studies have been conducted, and their results are not so conclusive as those reported in IBS.

ConclusionsLow FODMAP diets currently represent one of the mainstays in IBS management, because they are associated with symptom improvement (and thus with an improved quality of life) in 70% of patients. In order to prevent nutritional deficiency, it is advised that, after the FODMAP removal period (6–8 weeks) and the resultant clinical improvement, the foods should be gradually reintroduced so that the foods (and their amounts) that cause the symptoms in each patient can be identified. Studies are needed to identify the variables predicting for the effectiveness of this dietary model other than its adherence, and also to identify those patients who experience no clinical improvement. In these cases, nutrients of other types or other pathopysiological mechanisms may be involved.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest in relation to the article submitted.

Please cite this article as: Zugasti Murillo A, Estremera Arévalo F, Petrina Jáuregui E. Dieta pobre en FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols) en el síndrome de intestino irritable: indicación y forma de elaboración. Endocrinol Nutr. 2016;63:132–138.