So-called morning glory syndrome (MGS), although first described in 1929, owes its name to Kindler (1970).1 In this syndrome, congenital optic nerve dysplasia exists. The incidence of MGS is very low, and it is caused by the failure of the closure of the choroidal embryonic fissure. MGS, which has an autosomal dominant inheritance, is usually unilateral, although bilateral cases occur, predominates in females, and is characterized by a funnel-shaped excavation with central fibroglial tissue and radial retinal vessels mimicking the morning glory flower. MGS frequently occurs with isolated ophthalmological changes (decreased visual acuity associated with retinal detachment in 30–40% of patients), but systemic associations have been reported, including congenital anomalies in the forebrain and midline, with progressive endocrine, respiratory, or renal abnormalities.1,2

Congenital basal encephalocele (EB) is due to a skull bone and dura mater defect with extracranial herniation of cranial structures. It is a rare anomaly, difficult to diagnose, with an estimated incidence of 1:35,000 newborns. There are four types of encephalocele, of which the transsphenoidal variety is the least common (accounting for 5% of BEs).3 This type of encephalocele is due to the persistence of the craniopharyngeal or transsphenoidal canal, with brain tissue herniation through it. It may result from a defect in the floor of the sella turcica, the sphenoid sinus, or the posterior ethmoid sinus. The transsphenoidal transsellar variant is the least common. It is often associated with midline defects, with hypothalamic-pituitary hormone and optic nerve changes, including MGS.4 MGS is associated with 67% of BEs.

The incidence of hormone dysfunctions in patients with BE is 50–60%. GH deficiency, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, hypothyroidism, and diabetes insipidus are the most common disorders. A review of 15 cases with transsphenoidal BE showed that GH and antidiuretic hormone deficiencies were the most common (66.7 and 60% respectively), followed by gonadotropin (33.3%), TSH (26.7%), and prolactin deficiency (13.3%).5

The natural course of hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction is still uncertain, but progressive hormone dysfunction has been found in most patients with BE. Unfortunately, very few cases with endocrinological monitoring for 10 years or longer have been reported.3

We report a case of bilateral MGS associated with transsphenoidal encephalocele and panhypopituitarism in which imaging and hormonal studies were essential for diagnosis.

A 16-year-old female adolescent6/12 was referred for amenorrhea and delayed growth, which had been slow since infancy, but with no stagnation. Axillary hair growth and pubarche occurred at 11 years of age, but did not progress. Thelarche started at 16 years of age. No menarche occurred. The patient had no urinary frequency or polydipsia.

She had been born by normal delivery after a controlled 30-week pregnancy, and had a length of 49cm (+0.05SD) and a weight of 3240g (+0.44SD) at birth. At three months of age, the patient was diagnosed bilateral MGS, which caused at 11 years retinal detachment in the left eye and decreased vision in the right eye. She had no history of seizures or any other remarkable history.

A physical examination at 166/12 years revealed the following: height 145cm (−2.7SD), BMI 23.16kg/m2 (+0.98SD), target height 163cm (−0.15SD). Bone age of 149/12 years. Microphthalmos, right eye nystagmus, very thin upper lip, gothic palate. There was no goiter or fat accumulation in the abdomen. Tanner 2 pubertal stage. There were no other significant findings.

Hormone test results included: TSH 1.67μIU/mL (NR, 0.350–4.950), FT4 1.08ng/dL (NR, 0.700–1.600), basal cortisol: 21.20μg/dL (NR, 5.00–25.00), ACTH 50.3pg/mL (NR, 5–46). Response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia was normal (peak cortisol level, 26.7μg/dL). PRL 61.6ng/mL (NR, <20). Basal GH<0.05ng/mL with a peak of 0.06ng/mL (NR, >7) in the clonidine test with no estrogen priming. IGF1 86ng/mL (NR, 116–913). Basal FSH 2.77mIU/mL, basal LH 1.21mIU/mL. Estradiol 21pg/mL (NR in prepubescents <12pg/mL). A GnRH test showed a peak of FSH 7.46mIU/mL and LH 9.2mIU/mL. Bone densitometry showed osteoporosis of −3.2SD (at L1–L4 levels). Urinary osmolarity was not tested because there were no symptoms of diabetes insipidus.

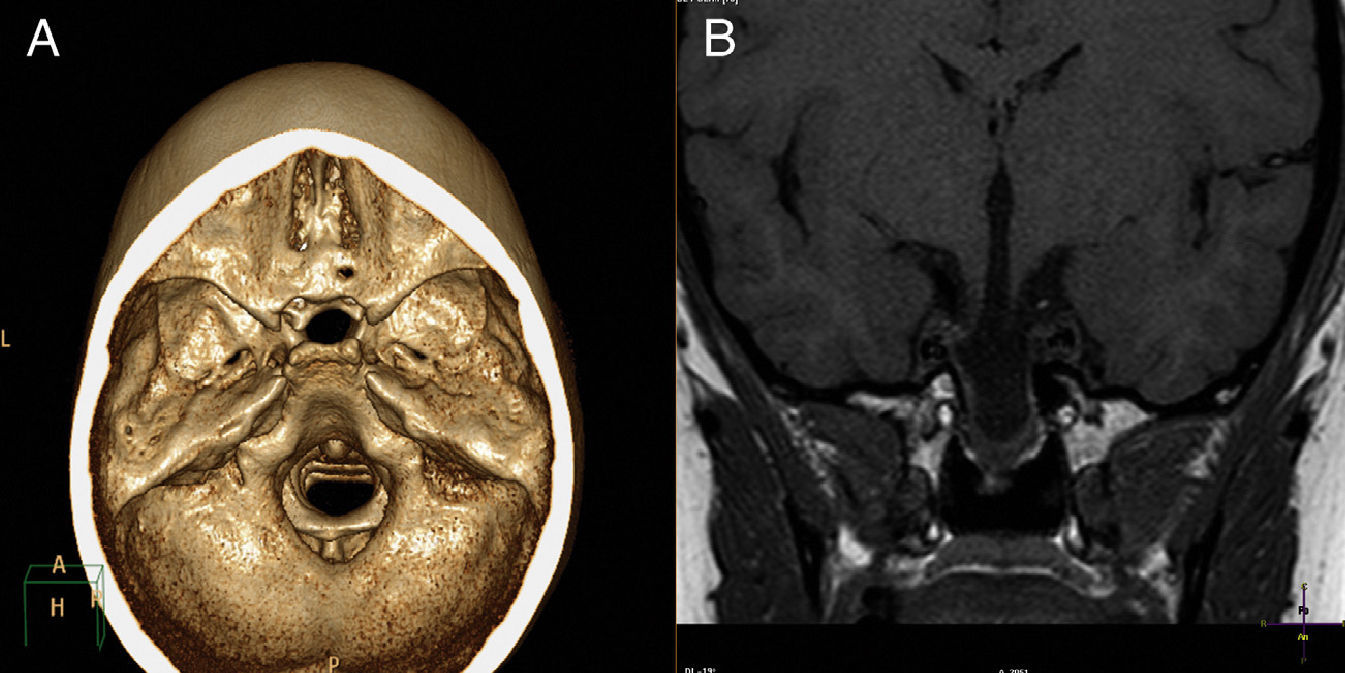

A CT scan with 3D reconstruction and MRI of the brain (Fig. 1) showed transsphenoidal meningoencephalocystocele, containing dysplastic hypothalamic-pituitary tissue in its lower part, agenesis of the rostrum of the corpus callosum, and a right retinal coloboma. Estrogen therapy was started with transdermal estrogens.6,7 GH was not administered because of bone age, as this treatment is clearly effective only if administered at an early age.8

Due to osteoporosis, calcium and vitamin D were started in addition to estrogen. Mild hyperprolactinemia could be attributed to elongation of the pituitary stalk. Surgical repair of encephalocele, as advocated by many authors, was not performed because it is often not beneficial due to the risk of damaging functioning tissue.9

Our patient had bilateral MGS associated with transsphenoidal encephalocele with endocrine changes, including GH and gonadotropin deficiency with a late diagnosis of hypothalamic-pituitary involvement, despite the fact that the history of the syndrome was known. We therefore emphasize the need for early endocrinological work-up and long-term follow-up, because hormone deficiencies may appear years after the initial diagnosis.3,10 A CT or MRI scan makes it possible to outline the anatomy of the herniated mass.

To sum up, MGS requires an imaging study to rule out encephalocele, and an assessment of hypothalamic-pituitary function for the early diagnosis and treatment of hormone deficiencies. The hormones mainly affected include GH, with an impact on final height, and gonadotropins with the resultant lack of estrogenization, which leads to early osteoporosis, in addition to a lack of pubertal development. Hormone replacement therapy is highly effective.6–8 It should be borne in mind that hormone deficiencies may be progressive and occur years after the initial diagnosis. Adequate monitoring of hypothalamic-pituitary axis function is therefore required.

Please cite this article as: Oyakawa Barcelli Y, García Durruti P, Enes Romero P, Martín Frías M, Barrio Castellanos R. Síndrome «morning glory» asociado a encefalocele transesfenoidal y panhipopituitarismo. Endocrinol Nutr. 2014;61:222–224.