To report the precautions taken by diabetic patients to avoid treatment errors and to provide advice to increase their safety.

MethodsA descriptive study of patients’ behaviors to minimize errors and tips by professionals to improve safety. Ninety-nine insulin-treated patients were randomly recruited from 3 primary healthcare centers and 2 hospitals. An opportunity sample of 33 doctors and nurses was also surveyed.

ResultsInformation of all prescriptions (p=0.005), review of doubts before the visit (p=0.009), and diet adherence (p=0.02) were the only precautions reported by patients who related to a lower number of patient errors. Female patients follow at-home instructions for blood glucose monitoring (odds ratio [OR] 0.07; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.1–0.6) better and use pillboxes to avoid errors (OR 0.23; 95% CI 0.1–0.6) more frequently than male patients. Male patients more commonly carry with them a card with information about allergies (OR 5.03; 95% CI 1.4–17.5). Patients with a longer course of disease tend to withhold information about other treatments from their doctors (β −15.8; 95% CI −23.2 to 8.4). For healthcare professionals, safety may increase if patients play a more active role in their treatment (91%), and inform their doctors about their different treatments (88%).

ConclusionsPromotion of patient autonomy, improved communication to patients, and systematic information about the most common medication errors may contribute to patient safety.

Describir qué hacen los pacientes diabéticos para evitar errores con el tratamiento y presentar consejos para incrementar la seguridad.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo de conductas de pacientes diabéticos tratados con insulina para minimizar errores y de consejos de los profesionales para mejorar la seguridad. Se reclutaron aleatoriamente 99 pacientes de 3 centros de salud y 2 hospitales. Adicionalmente, se contó con una muestra de oportunidad de 33 médicos y enfermeros.

ResultadosInformar de todas las prescripciones (p=0,005), revisar dudas antes de la consulta (p=0,009) y el cumplimiento de la dieta (p=0,02) fueron las únicas precauciones informadas por los pacientes que se relacionaron con un menor número de errores de los propios pacientes. Las mujeres siguen mejor en casa las indicaciones sobre los controles de glucemia (odds ratio 0,07, intervalo de confianza [IC] del 95%: 0,1-0,6) y recurren a pastilleros para evitar errores (odds ratio: 0,23; IC 95%: 0,1-0,6) con más frecuencia que los hombres. La información de alergias es más frecuente entre varones (odds ratio: 5,03; IC 95%: 1,4-17,5). Los pacientes con un curso más prolongado tienden a no proporcionar información a su médico sobre otros tratamientos (β −15,8, IC95% −23,2-8,4). Para los profesionales, la seguridad aumentaría si el paciente ejerciera un rol más activo (91%) y si informara de los tratamientos que sigue (88%).

ConclusionesFomentar la autonomía del paciente, mejorar la comunicación con el paciente e informarle sistemáticamente de los errores de medicación más frecuentes entre los pacientes pueden contribuir a la seguridad.

Approximately 10% of hospitalized patients1,2 and 7% of those seen in primary care3 may be expected to experience an adverse event. Different approaches have been used to increase patient safety, such as hand washing, no bacteremia, no pneumonia, site surgery, adequate patient and procedure. The role of patients themselves in their safety has also been emphasized.4–7 More recently, the type and frequency of errors that patients tend to make have also been analyzed.8–10

Adverse events are particularly more common among diabetic patients.1,3 To improve their safety, patients must be provided with the necessary information to avoid the risks associated with treatments.6 However, few studies are available about how diabetic patients may contribute to their safety.

Sarkar et al.11 found that up to 59% of patients with type 2 diabetes made mistakes in the self-administration of medication and 21% in diet. Inadequate insulin administration,12 age and dependence on third persons have been related to a rise in the number of errors made by patients.13–15

The purpose of this study was to describe the precautions taken by diabetic patients to avoid the most commonly made mistakes in the course of treatment. Some tips that professionals think may increase patient safety are also given.

Materials and methodsA descriptive study based on surveys given to diabetic patients being treated with insulin and to professionals who directly see this type of patient. The study was conducted from February to May 2010 at three health centers and two hospitals in Alicante and Madrid (Spain).

The patients completed a questionnaire consisting of 22 dichotomic questions about their usual precautions in treatment and marked on a list of 18 potential errors related to self-care and medication which they recognized they had made at some time. Healthcare professionals completed a 26-item questionnaire (on a scale ranging from 0, ‘I would not advise it’, to 10, ‘highly advisable’) about tips for diabetic patients so as to enable them to avoid confusion, forgetfulness, or errors in medication or self-care.

The questionnaires were based on a qualitative study conducted one year before,15 and were checked for consistency using Cronbach's alpha and for validity using the Jöreskog–Sörbom goodness-of-fit index (GFI).

A total of 100 patients, 50% of them women, were planned to be surveyed (the sample size was calculated to estimate proportions with a 5% precision). The patients were selected by days of the week being chosen at random to recruit patients attending the clinic on that day. To participate in the study, patients had to meet the following inclusion criteria: age over 18 years, insulin treatment for at least three years, and the ability to answer a questionnaire. The patients were asked for their consent to participate after they had been informed about the reasons for the study, what their participation would involve, the use that would be made of the data collected, and their condition of anonymity, as well as their possibility of terminating the questionnaire at any time. If a patient declined to complete the questionnaire, he/she was replaced by another patient, also recruited randomly, and so on until the sample size was completed. The questionnaire refusal rate did not exceed 5%.

The professionals were selected through invitation by electronic mail in order not to affect their work schedule. A total of 75 healthcare professionals (double the number usually considered as adequate for studies using Delphi methodology) recruited among members of scientific societies and professional associations, or professionals attending patient safety courses, were invited to answer, the regulations on personal data protection and the anonymity of participants being respected. Inclusion criteria were as follows: specialists in family and community medicine, public health or endocrinology, and primary care nurses, who were not currently the subject of a civil suit, and who had at least three years experience.

Data analysis used univariate statistics (mean, standard deviation, and percentages) and a Chi-square test to analyze categorical variables. To identify what patients did to avoid mistakes, a logistic regression analysis was performed with the forward stepwise method (Wald). To identify strategies in order to avoid age-related errors, a linear regression analysis using a sequential stepwise method was performed. A high agreement was considered to exist between professionals when values of 8 or higher were assigned (on a 0–10 scale).

The study was approved by the research committee of Universidad Miguel Hernández.

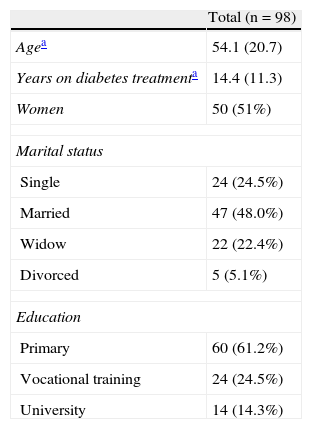

ResultsA total of 99 patients with a mean age of 54 years (95% CI, 50–58) were interviewed (Table 1), and the opinion of 33 professionals (29 physicians – 6 of them tutors of resident intern physicians – and 4 nurses) was collected. One patient did not complete the procedure, and his answers were not included in the analyses.

Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.78 to 0.97) and validity (Jöreskog–Sörbom's GFI ranging from 0.89 to 0.98) of instruments used were verified.

The precautions usually taken by patients to avoid errors were classified according to self-care activity (Table 2). Most patients (97%) reported daily glucose monitoring. Twenty percent did not usually change the insulin injection site. Most of them were attentive to changes in medication in order to avoid mistakes in medication (92%). Less frequent precautions taken by patients included written notes to remind themselves of questions to be asked (39%), attending the office with another person (48%), or taking with them a card indicating possible allergies (17%). These precautions were not related to the frequency with which patients stated that they had made errors of omission or commission during the course of treatment (Table 2).

Precautions taken by patients during diabetes treatment to avoid medication confusion, forgetfulness, or errors, as reported by patients themselves.

| Patients (n=98) | Greater error frequency*p value | |

| Blood glucose testing and insulin self-administration | ||

| I continue with treatment as instructed by my physician even if my glucose is controlled | 95 (96.9) | 0.88 |

| I make home controls and measure my glucose level as instructed | 90 (90.9) | 0.30 |

| I usually change the site where I inject myself with insulin | 78 (79.6) | 0.55 |

| Management of medication | ||

| I take my medication and do not forget it even if I eat out | 92 (92.9) | 0.52 |

| I am very careful when taking medicines, particularly when they change my medication, so as not to confuse pills | 90 (91.8) | 0.11 |

| I am very careful when taking medicines in relation to meals | 88 (88.9) | 0.44 |

| I use pill boxes/medicine-sorting boxes so as always to have my medication well-organized and to avoid mistakes | 44 (44.4) | 0.21 |

| Active role during medical visit | ||

| When doctors or nurses tell me anything I do not understand, I always ask in order to know what I have to do | 89 (89.9) | 0.06 |

| I always keep doctor's reports | 83 (83.8) | 0.61 |

| I keep notes on all treatments that doctors say I should take | 80 (80.8) | 0.28 |

| I carefully read the information given to me at the healthcare center | 77 (77.8) | 0.15 |

| I carry with me to visits to doctors or nurses a note with all my doubts and questions so that I do not forget them | 39 (39.4) | 0.23 |

| Quality of information provided to patients | ||

| I always get information about all pills and treatments I am taking, even if prescribed by another doctor | 88 (88.9) | 0.005 |

| I always give information about my allergies | 59 (59.6) | 0.79 |

| Before I go to the clinic, I review everything I have to ask the doctor and all I have to tell him so that he can make an appropriate clinical judgment | 55 (55.6) | 0.009 |

| Rules and habits, self-care | ||

| I take care in identifying food rich in carbohydrates | 76 (77.6) | 0.02 |

| I review and take care of my feet daily | 63 (64.3) | 0.35 |

| I usually do the physical exercise recommended for me | 62 (62.6) | 0.55 |

| I try and eat 5 meals daily | 60 (61.2) | 0.008 |

| Other precautions | ||

| When in doubt, I ask other more experienced patients | 48 (48.5) | 0.81 |

| I usually go to the clinic with some relative to help me remember what I have been told | 43 (43.4) | 0.45 |

| I always carry with me a card stating what I am allergic to | 17 (17.2) | 0.13 |

Between brackets, %.

Fewer errors were made by patients who stated that they informed their physicians of all treatments they were using, including those prescribed by other physicians (rho −0.3, p=0.005), who reviewed what they should tell their physicians before entering the office (rho −0.3, p=0.0009), who took more care to identify carbohydrate-rich food (rho −0.2, p=0.02) and who tried to eat five meals daily (rho −0.3, p=0.008).

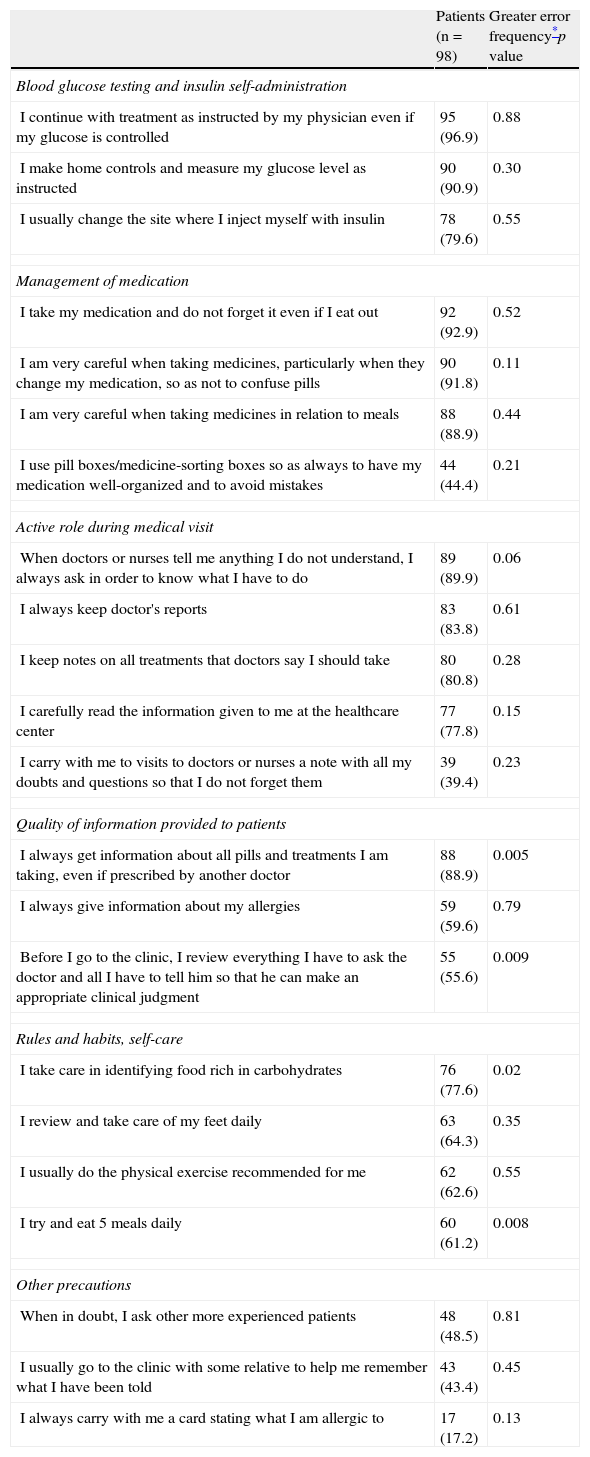

Hardly any differences were found between males and females regarding the strategies used to avoid errors (Table 3). While women reported more frequent use of pill boxes (OR 0.2; 95% CI −0, 1) and made home blood glucose tests more often than men (OR 0.1; 95% CI 0, 1), male patients said that they carried with them a card with known allergies five times more frequently than women (OR 5; 95% CI 1, 17).

Sex differences in the use of precautions to increase safety.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | ||

| I make home controls and measure my glucose level as instructed | 0.07 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

| I always carry with me a card stating what I am allergic to | 5.03 | 1.4 | 17.5 |

| I use pill boxes/medicine-sorting boxes so as to always have medication well-organized and to avoid mistakes | 0.23 | 0.1 | 0.6 |

Results of logistic regression analysis using the forward stepwise method (Wald). CI: confidence interval; dependent variable: patient sex: 0 female, 1 male.

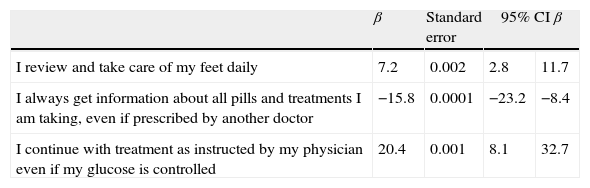

Young patients more frequently reported to their physicians other treatments they were taking (β −16, 95% CI −23, −8) (Table 4). By contrast, older patients reported greater compliance with treatment (β 20; 95% CI 8, 33) and foot care (β 7; 95% CI 3, 12). No other age-related differences were found.

Differences in the use of precautions to increase safety by number of years on treatment.

| β | Standard error | 95% CI β | ||

| I review and take care of my feet daily | 7.2 | 0.002 | 2.8 | 11.7 |

| I always get information about all pills and treatments I am taking, even if prescribed by another doctor | −15.8 | 0.0001 | −23.2 | −8.4 |

| I continue with treatment as instructed by my physician even if my glucose is controlled | 20.4 | 0.001 | 8.1 | 32.7 |

Results of linear regression analysis by the sequential stepwise method.

CI: confidence interval; dependent variable: years on treatment.

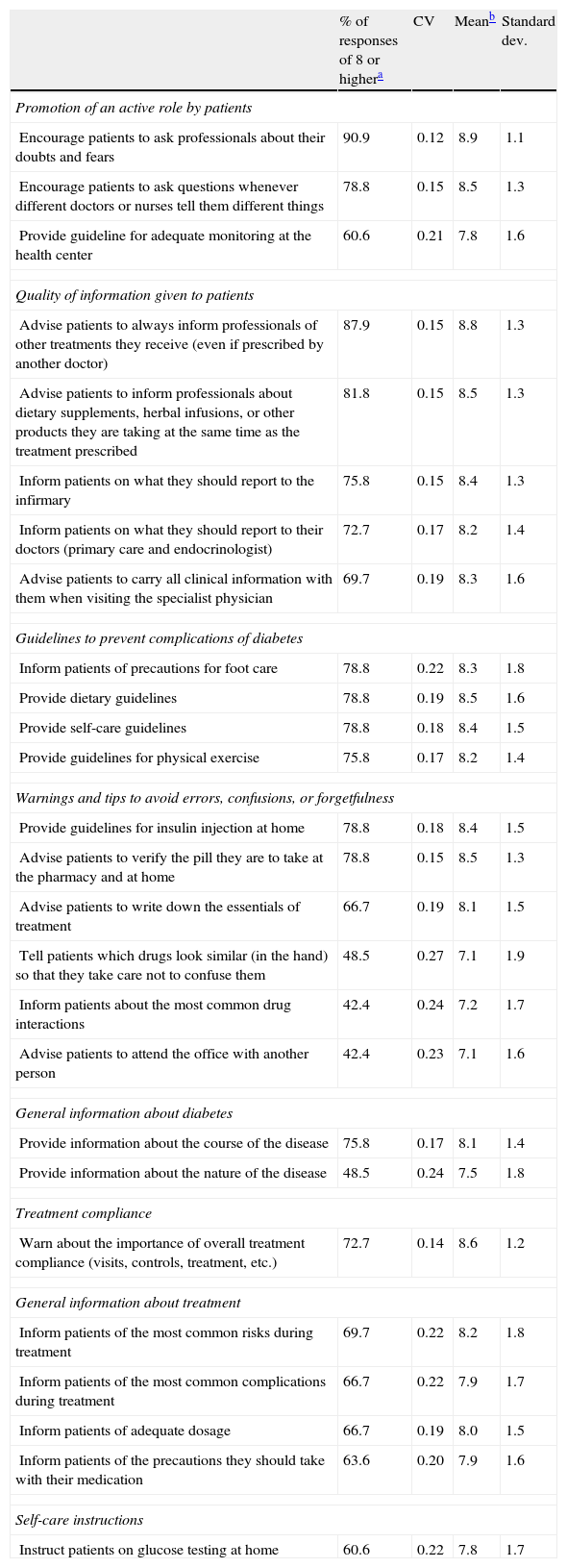

Table 5 shows tips by professionals for helping patients to minimize errors. Professionals prioritized the assumption of an active role by patients (proportion of professionals assigning 8 or more points, 91%) and giving information to physicians about all treatments (drugs or any other) received (88% assigned 8 or more points). By contrast, professionals had some doubts about the effectiveness of training patients to differentiate drugs based on their appearance (48% assigned 8 or more points), patient attendance to the office with another person (42% assigned 8 or more points), and informing patients of potential drug interactions (42% assigned 8 or more points).

Tips of healthcare professionals for diabetic patients to avoid confusion, forgetfulness, or errors in medication or self-care (n=33).

| % of responses of 8 or highera | CV | Meanb | Standard dev. | |

| Promotion of an active role by patients | ||||

| Encourage patients to ask professionals about their doubts and fears | 90.9 | 0.12 | 8.9 | 1.1 |

| Encourage patients to ask questions whenever different doctors or nurses tell them different things | 78.8 | 0.15 | 8.5 | 1.3 |

| Provide guideline for adequate monitoring at the health center | 60.6 | 0.21 | 7.8 | 1.6 |

| Quality of information given to patients | ||||

| Advise patients to always inform professionals of other treatments they receive (even if prescribed by another doctor) | 87.9 | 0.15 | 8.8 | 1.3 |

| Advise patients to inform professionals about dietary supplements, herbal infusions, or other products they are taking at the same time as the treatment prescribed | 81.8 | 0.15 | 8.5 | 1.3 |

| Inform patients on what they should report to the infirmary | 75.8 | 0.15 | 8.4 | 1.3 |

| Inform patients on what they should report to their doctors (primary care and endocrinologist) | 72.7 | 0.17 | 8.2 | 1.4 |

| Advise patients to carry all clinical information with them when visiting the specialist physician | 69.7 | 0.19 | 8.3 | 1.6 |

| Guidelines to prevent complications of diabetes | ||||

| Inform patients of precautions for foot care | 78.8 | 0.22 | 8.3 | 1.8 |

| Provide dietary guidelines | 78.8 | 0.19 | 8.5 | 1.6 |

| Provide self-care guidelines | 78.8 | 0.18 | 8.4 | 1.5 |

| Provide guidelines for physical exercise | 75.8 | 0.17 | 8.2 | 1.4 |

| Warnings and tips to avoid errors, confusions, or forgetfulness | ||||

| Provide guidelines for insulin injection at home | 78.8 | 0.18 | 8.4 | 1.5 |

| Advise patients to verify the pill they are to take at the pharmacy and at home | 78.8 | 0.15 | 8.5 | 1.3 |

| Advise patients to write down the essentials of treatment | 66.7 | 0.19 | 8.1 | 1.5 |

| Tell patients which drugs look similar (in the hand) so that they take care not to confuse them | 48.5 | 0.27 | 7.1 | 1.9 |

| Inform patients about the most common drug interactions | 42.4 | 0.24 | 7.2 | 1.7 |

| Advise patients to attend the office with another person | 42.4 | 0.23 | 7.1 | 1.6 |

| General information about diabetes | ||||

| Provide information about the course of the disease | 75.8 | 0.17 | 8.1 | 1.4 |

| Provide information about the nature of the disease | 48.5 | 0.24 | 7.5 | 1.8 |

| Treatment compliance | ||||

| Warn about the importance of overall treatment compliance (visits, controls, treatment, etc.) | 72.7 | 0.14 | 8.6 | 1.2 |

| General information about treatment | ||||

| Inform patients of the most common risks during treatment | 69.7 | 0.22 | 8.2 | 1.8 |

| Inform patients of the most common complications during treatment | 66.7 | 0.22 | 7.9 | 1.7 |

| Inform patients of adequate dosage | 66.7 | 0.19 | 8.0 | 1.5 |

| Inform patients of the precautions they should take with their medication | 63.6 | 0.20 | 7.9 | 1.6 |

| Self-care instructions | ||||

| Instruct patients on glucose testing at home | 60.6 | 0.22 | 7.8 | 1.7 |

CV: coefficient of variation in answers to each item: standard deviation/mean.

Patients and professionals agreed that, in order to prevent errors, patients should play a more active role, provide more complete information about how they cope with the disease and treatment, and ensure that they comply with the instructions related to diet and insulin. These results confirm that reinforcing patient autonomy contributes to an improvement in results.5,16,17

Greater coordination between levels and communication skills would increase the quality of care and contribute to a decrease in adverse events. This study demonstrated that coordination failures and communication deficits decrease safety. It also showed that, in patient monitoring, professionals should reinforce information about how to cope with the most common errors so as to help patients to avoid making them.11

Other studies18–20 have demonstrated that many patients (up to 64% according to estimates) take a rather passive role, and up to 26% have unresolved doubts about their disease and treatment. Most patients overestimate treatment safety.21 The results of this research may be applicable to diabetes in general. For example, older patients prefer to take a more passive role, which is known to be associated with an increased risk of experiencing an adverse event.7,22

This study also demonstrated that the advice currently being given to patients to prevent adverse events23,24 is often not followed. Except for the recommendation that they inform their doctor about all treatments (including natural therapies) regardless of the prescriber, such precautions do not appear to be taken with the desired frequency.

Indirectly, these results appear to suggest that patients do not completely feel that they play an active role in their own safety.25 The fact that the patients who made the most mistakes did not practice behavior to avoid them more often should prompt us to place a greater emphasis on this aspect, since patients are active agents in the care process.26–28

Although a greater sample size and scope would be needed, women appear to take more precautions with blood glucose monitoring and to be better organized in the use of medication. It should also be noted that patients learn from experience, and some of these precautions become more frequent over time. It should however be noted that there is a trend over the years for patients not to inform physicians of other treatments being received. Bearing in mind professional recommendations, it is important that during patient monitoring, the necessity of reporting concomitant medications should be emphasized as a way of preventing frequent patient errors and so increasing patient safety. If treatment education programs could include this information, greater clinical safety would be achieved.

When interpreting the data, it should be borne in mind that the sample was not representative of all diabetic patients being treated. Thus, the proportion of single people in the sample was high. To increase sincerity in answering, we did not inquire about clinical or personal patient variables. However, a social desirability effect that obscures the frequency with which precautions are taken may be expected when patients are asked to inform about such measures. Patient understanding of the disease, drug number and dosage, or treatment compliance were not studied. Finally, metabolic control results, as well as other sources of information, were not considered, although some admissions occurred due to hyperglycemia attributable to the errors of patients themselves, which would allow for some verification of subjective with objective information. Precisely one of the future research areas could be to analyze whether inclusion in treatment education programs of information about common errors and strategies to avoid them has a positive impact on patient clinical status and safety.

Based on the results reported, it appears advisable to promote active patient participation (autonomy), to improve the capacity of professionals for more effective communication with patients, especially as regards communication failures which contribute to patient errors in medication, and to include in treatment education programs specific information about the types of errors most frequently made by patients, which both restrict treatment effectiveness and represent a risk for their clinical condition.

FundingThis study is part of a project on patient errors supported by the Healthcare Research Fund, as well as by FEDER funding, reference PI08-90118.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Mercedes Guilabert, Isabel María, and Alicia Peralta contributed to data collection and database preparation. Jesús Casal and José Antonio Picó reviewed the instruments used and made suggestions to improve them. José Francisco Herrero, Domingo Orozco, Vicente Gil, Lidia Ortiz, Antonio Ochando, and Encarnación Hernández collaborated unselfishly in the research at different times.

Please cite this article as: Mira JJ, et al. ¿Qué hacen y qué deben hacer los pacientes diabéticos para evitar errores con el tratamiento? Endocrinol Nutr. 2012;59(7):416–22.