We present the case of a 23-year-old male from Mali who came into Accident and Emergency with eye pain and loss of vision in his right eye. Physical examination revealed conjunctival hyperaemia, non-reactive pupil, positive Tyndall effect, posterior synechiae and rubeosis of the right iris. Fundus examination revealed a right choroidal lesion with associated retinal detachment, which was confirmed by ultrasound of the eye (Fig. 1). The patient was also found to have painful right submandibular lymphadenopathy of a hard consistency.

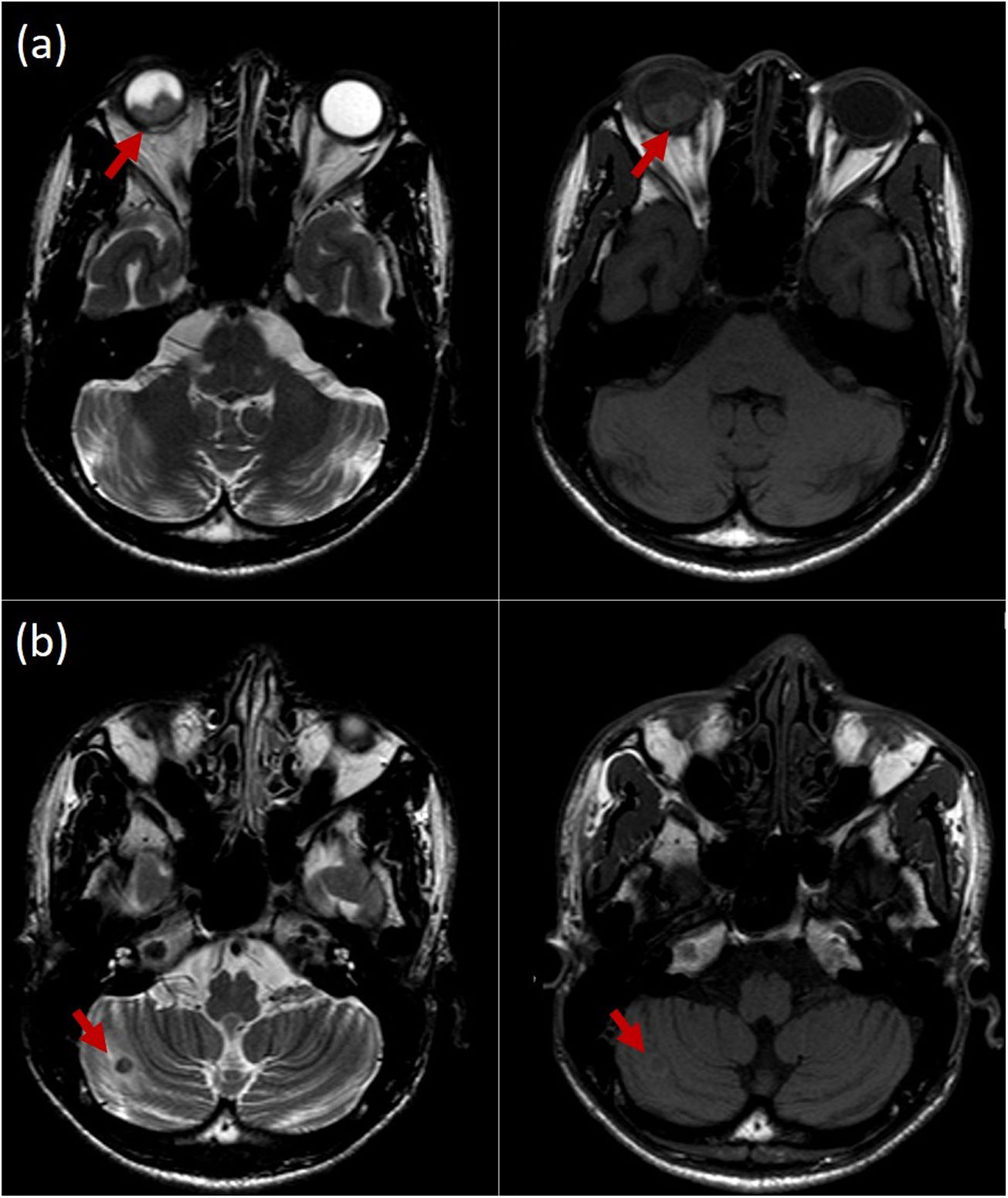

He was admitted for further study. Orbital MRI revealed a complete retinal detachment of the right eye secondary to cystic elevated retinal lesions, occupying the lower quadrants of the eyeball (Fig. 2A). The described findings raised the differential diagnosis between cystic retinal tumour, parasitic cysts and, less likely, haemorrhagic intraretinal cysts. A space-occupying lesion was also seen in the right cerebellar hemisphere (Fig. 2B).

Clinical courseInitially, full blood count, conventional biochemistry and a systematic urine test were carried out, showing results within the normal ranges. Subsequent infectious disease-specific studies included screening of the sub-Saharan patient and ruled out intestinal parasitosis, strongyloidiasis, filariasis, genitourinary parasitosis, malaria and leishmaniasis. Serology was also requested for Treponema pallidum, CMV, HSV-1, HSV-2, HIV, EBV, HBV, HCV, VZV and Toxoplasma, all of which were negative. However, the Mantoux test was positive.

A biopsy of the right submandibular lymphadenopathy was performed, with outflow of caseous material and a microbiological result (smear microscopy and PCR) of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. The patient started treatment with rifampicin and isoniazid for 12 months, and pyrazinamide and ethambutol for the first two months.

At the same time, given the patient's poor progress, it was decided to enucleate his right eyeball, with pathology findings of necrotising granulomatous inflammation of the choroid and retina in the lower quadrants, with negative Ziehl-Neelsen staining.

As disseminated tuberculosis was suspected, it was decided to complete the extension study with a chest CT scan, which showed only bilateral patchy consolidations, indicating the existence of reactivated pulmonary tuberculosis, and an [18F]-FDG PET/CT scan, which showed multiple hypermetabolic lesions in the pulmonary parenchyma, predominantly on the left, with supradiaphragmatic lymph node involvement, and liver and bone lesions of high metabolic grade, which appeared to correspond to the same infectious process (Fig. 3).

A) [18F]-FDG PET/CT showed multiple hypermetabolic lesions in lung parenchyma, predominantly on the left, with supradiaphragmatic and hepatic lymph node involvement and numerous high metabolic grade bone lesions (maximum intensity projection [MIP]). B) Right submandibular hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy (axial image). C) Left lung lesions of high metabolic grade (axial image). D) Vertebral and sternal bony involvement (sagittal image).

One year later, the patient had made a good recovery. The follow-up CT scan after the end of treatment showed that all the lesions recorded had disappeared.

Closing remarksTuberculosis is a major global public health problem, being one of the 10 leading causes of death among adults worldwide.1 Extrapulmonary tuberculosis accounts for 14% of all cases of tuberculosis, and most commonly affects the lymph nodes, followed by the pleura.2 The general constitutional symptoms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis are often absent, which delays diagnosis.2

Posterior uveitis is the most common form of eye involvement in tuberculosis. It is characterised by a wide spectrum of fundoscopic findings, such as multifocal or serpiginous choroiditis, tuberculomas, neuroretinitis, ischaemic retinal vasculitis and endophthalmitis.3 In our case, it presented as a necrotising granulomatous inflammation of the choroid and retina, with negative smear microscopy.

The diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis is often presumptive.3 Definitive diagnosis is based on the demonstration of tubercle bacilli in the tissue, but this involves the difficulty of obtaining a biopsy. In most cases, a combination of evidence of systemic disease, characteristic eye findings and a trial of therapeutic treatment is used to arrive at a diagnosis.3

We have presented here the case of a patient from sub-Saharan Africa, whose initial clinical manifestation was eye pain and loss of vision. The findings described raised the differential diagnosis between retinal cystic tumours such as choroidal melanoma, parasitic cysts and, less likely, haemorrhagic intraretinal cysts.

Parasitic eye lesions (protozoa such as Acanthamoeba spp., species of Leishmania, Angiostrongylus, Loa loa, species of Dirofilaria and flatworms such as Taenia solium and Schistosoma spp.) can produce severe acute inflammation of the surrounding tissue which may mask an inflammatory eye mass.4

Given the patient's background, the diagnosis was challenging and the differential diagnosis had to be broadened to rule out infectious (intestinal parasitosis, strongyloidosis, filariasis, genitourinary parasitosis, malaria and leishmaniasis) and non-infectious (cancerous) diseases. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis should also be considered when screening patients from sub-Saharan Africa.5

The [18F]-FDG PET/CT is of diagnostic value in the study of the extent of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, as well as in the assessment of response to treatment.6 In our case, it was more useful than CT in determining the extent of the disease.

Ethical considerationsWritten informed consent was obtained from the patient for the anonymised use of clinical data and images. All procedures performed in this study with human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the local hospital's Independent Ethics Committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards.

FundingThe authors declare that they received no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

![A) [18F]-FDG PET/CT showed multiple hypermetabolic lesions in lung parenchyma, predominantly on the left, with supradiaphragmatic and hepatic lymph node involvement and numerous high metabolic grade bone lesions (maximum intensity projection [MIP]). B) Right submandibular hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy (axial image). C) Left lung lesions of high metabolic grade (axial image). D) Vertebral and sternal bony involvement (sagittal image). A) [18F]-FDG PET/CT showed multiple hypermetabolic lesions in lung parenchyma, predominantly on the left, with supradiaphragmatic and hepatic lymph node involvement and numerous high metabolic grade bone lesions (maximum intensity projection [MIP]). B) Right submandibular hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy (axial image). C) Left lung lesions of high metabolic grade (axial image). D) Vertebral and sternal bony involvement (sagittal image).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/2529993X/0000004200000004/v3_202405261058/S2529993X24000078/v3_202405261058/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr3.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)