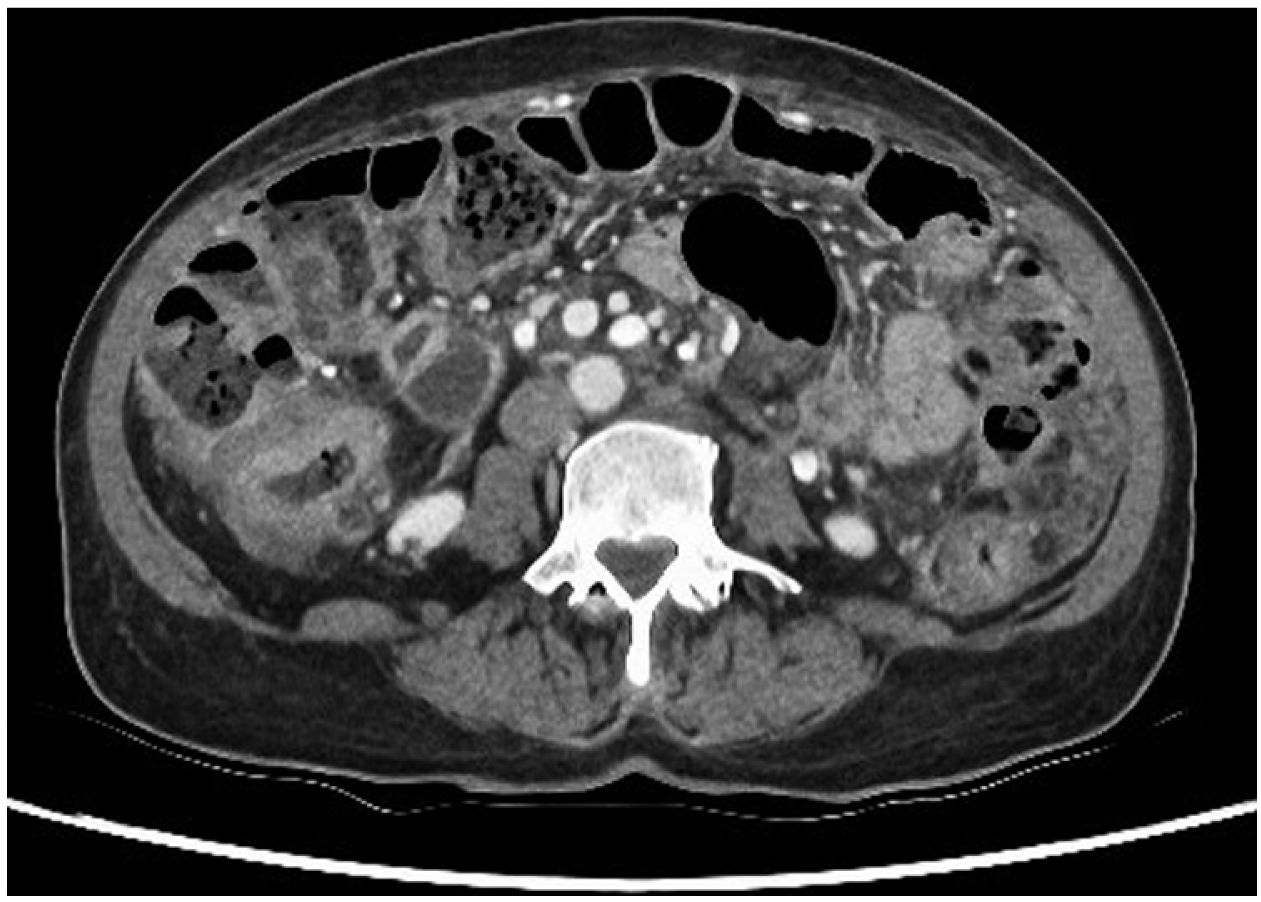

This was a 62-year-old woman from Peru with a history of rheumatoid arthritis on treatment with methotrexate, adalimumab and prednisone. She went to Accident and Emergency after several weeks of symptoms of general malaise, asthenia, weight loss of 6kg and abdominal pain. In the initial assessment, the full range of laboratory tests showed neutrophilia with elevation of inflammatory markers, the rest of the parameters being normal, and CT of chest, abdomen and pelvis showed wall thickening in the colon compatible with primary synchronous neoplasms, and ascites with omental lesions indicative of peritoneal carcinomatosis (Fig. 1); there were no abnormal findings in the chest. Diagnostic paracentesis showed lymphocytic ascites and elevated adenosine deaminase, with no microorganisms visible on the Gram stain.

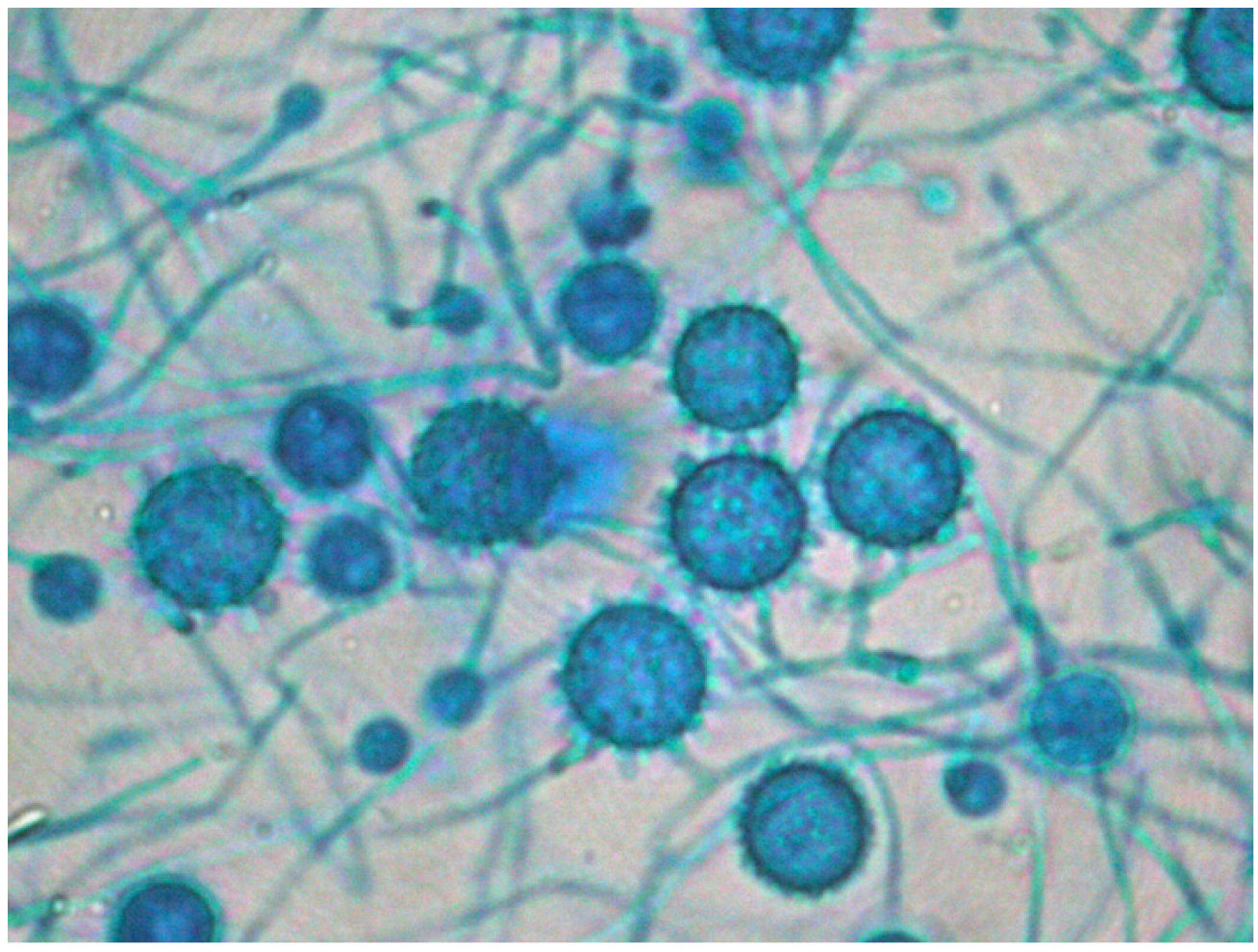

The patient was admitted to Internal Medicine. After a week in the hospital, the patient had haematemesis with haemorrhagic shock, which required transfusion support. An abdominal CT angiogram confirmed a focus on active arterial bleeding in the sigmoid colon. Once the patient had been stabilised, gastro-colonoscopy showed a Forrest III oesophageal ulcer and multiple ulcers in the colon, but with no active bleeding (Fig. 2). Samples were taken for pathology and microbiology (culture of bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi and PCR of viruses). The preliminary pathology report was of a granulomatous infiltrate with foci of necrosis, with no cells suggestive of malignancy. Despite the atypical presentation, tuberculosis of the gastrointestinal tract was considered a possibility, but we did not start antituberculous therapy as the microbiological results were still pending.

Three days after admission, the patient went into shock with desaturation. She had marked elevation of inflammatory parameters without anaemia. She was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit due to her haemodynamic and respiratory instability.

Within a few hours, the patient required orotracheal intubation and perfusion of high-dose vasopressors in the context of refractory shock and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Laboratory tests showed increased inflammatory parameters, coagulopathy, acute kidney injury and mixed hypertransaminasaemia with new-onset hyperbilirubinaemia. As septic shock was suspected, despite the lack of microbiological isolates, broad-spectrum antimicrobial treatment was started with isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, levofloxacin and linezolid (assuming the possibility of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis given where the patient was from), along with meropenem and amphotericin-B.

PCR for tuberculosis (GeneXpert®, Cepheid, Sunnyvale, California, USA) and viruses in a gastrointestinal ulcer sample were negative, as was the plasma Interferon-Gamma Release Assay (IGRA), so it was decided to stop anti-tuberculous therapy, maintaining meropenem, linezolid and amphotericin-B for suspected bacterial or fungal aetiology.

Gastrointestinal ulcer cultures were negative on day 10 of admission, along with negative blood, urine, faeces and bronchoalveolar lavage cultures, negative cytomegalovirus viral load, and negative serologies for Strongyloides and atypical viruses and bacteria.

The patient made progressive respiratory and haemodynamic improvement after her second week in the hospital, enabling her to be extubated and the dose of vasopressors reduced.

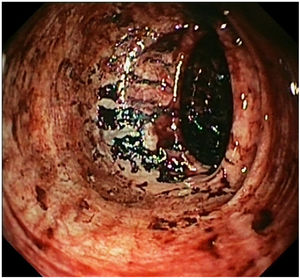

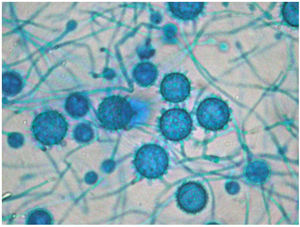

The definitive Pathology report was of gastrointestinal ulcers with visible signs of fungal structures, with no cells indicative of malignancy. This information raised the possibility of disseminated histoplasmosis, confirmed after the growth of Histoplasma capsulatum (H. capsulatum) in cultures on admission day 16 (Fig. 3), combined with a positive plasma immunodiffusion study.

Antibiotics were withdrawn, continuing the amphotericin-B, with progressive clinical improvement. Once oral tolerance was verified, and after 22 days of treatment, itraconazole was started, and she was discharged to a normal hospital ward, where she continued to improve.

DiscussionHistoplasmosis is a mycosis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum, which is endemic in North America and several countries in Latin America1,2. It is generally asymptomatic in immunocompetent patients. In symptomatic cases, acute pulmonary presentation is most common as a self-limiting, nonspecific respiratory condition complicated by pericarditis, mediastinal lymphadenopathy, lung nodules, pericarditis or ARDS, or a chronic infection similar to tuberculosis. However, in immunosuppressed patients, with a frequency of approximately 1 in 2000 patients2, it can progress as a disseminated infection with the involvement of several organs, the main risk factors for this being infection by human immunodeficiency virus, solid organ transplant, treatment with anti-tumour necrosis factor and advanced age. In these cases, patients may develop symptoms such as peripheral lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias, impaired liver function, interstitial lung infiltrates, skin lesions, meningoencephalitis and ulcerative lesions or masses in the gastrointestinal tract3–5. Disseminated infection is treated with amphotericin-B for 14 days or until clinical improvement, with subsequent transition to oral itraconazole until completing 12 months of treatment or while immunosuppression persists6,7.

Our patient's atypical presentation stands out, with no cytopenia, organomegaly, lymphadenopathy, skin lesions or pulmonary symptoms at the beginning and predominantly abdominal symptoms even though. However, up to 70% of patients have abdominal involvement; this is most often asymptomatic and, in many cases, only detected in the post-mortem examination4.

We should always, therefore, consider the possibility of an endemic mycosis in an immunosuppressed patient from these regions and, although we may be making the differential diagnosis with other infections (bacterial or mycobacterial) and inflammatory diseases (sarcoidosis or inflammatory bowel disease), it is essential to take adequate microbiology samples and start the treatment empirically, as these results take time to obtain. The delay could be fatal for the patient.

FundingNo funding was received.