We read with interest the study conducted by Monreal et al.1 which reported an increased prevalence of HIV infection in patients hospitalised due to stroke, regardless of classic cardiovascular risk factors, which supports the role of HIV infection as an independent risk factor. We believe that this is a very important subject, so we would like to make a few remarks.

Firstly, it would be useful to know some of the more specific characteristics of the stroke patients, in order to assess the results. In this regard, the study's lack of stratification by age, time since onset of HIV infection, antiretroviral therapy received and stimulant drug use, which is more common in some groups,2,3 may have acted as confounding factors in the analysis of the results. Moreover, during the study period, major changes in HIV treatment occurred. It would be very useful to know all these things with a view to proposing modifications to the management of these patients.

It is well established that HIV enters the central nervous system (CNS) in the week following infection,4 which causes activation of macrophages and microglia, as well as dysfunction of astrocytes due to direct action of proteins particular to HIV, such as gp120 and gp140,5 which generate a pro-inflammatory reaction due to release of cytokines. All this gives rise to early local immune activation processes, which cause neuron damage.6 In addition, different antiretroviral drugs enter the CNS differently, as reported in a classification from Letendre et al. in 20087; this may be a very important factor to bear in mind.

Second, it is important to stress that, according to figures from the Strategic Plan for Prevention and Management of HIV Infection, it is estimated that one in every five HIV+ individuals are not aware of their serological status,8 contributing to continuous transmission. In addition, 50% of patients are diagnosed late, with less than 350 CD4/μl lymphocytes, which results in a worse prognosis and greater resource consumption.

To combat this problem, various screening strategies have been proposed; it is not clear in Spain if the screening strategy should be universal or focused on particular risk groups and which ones these are depending on care level.9 The official stroke diagnosis and treatment guidelines from the Sociedad Española de Neurología [Spanish Society of Neurology]10 recommend syphilis serology in young patients with cryptogenic or recurrent transient ischaemic attack (TIA) and unspecified serologies in the aetiological diagnosis of stroke.

Reducing rates of occult and late diagnosis should be a shared objective. In 2019, 61 new cases of HIV infection were diagnosed at our centre. We determined whether they had visited the emergency department or had been admitted to the hospital in the five years prior to diagnosis.

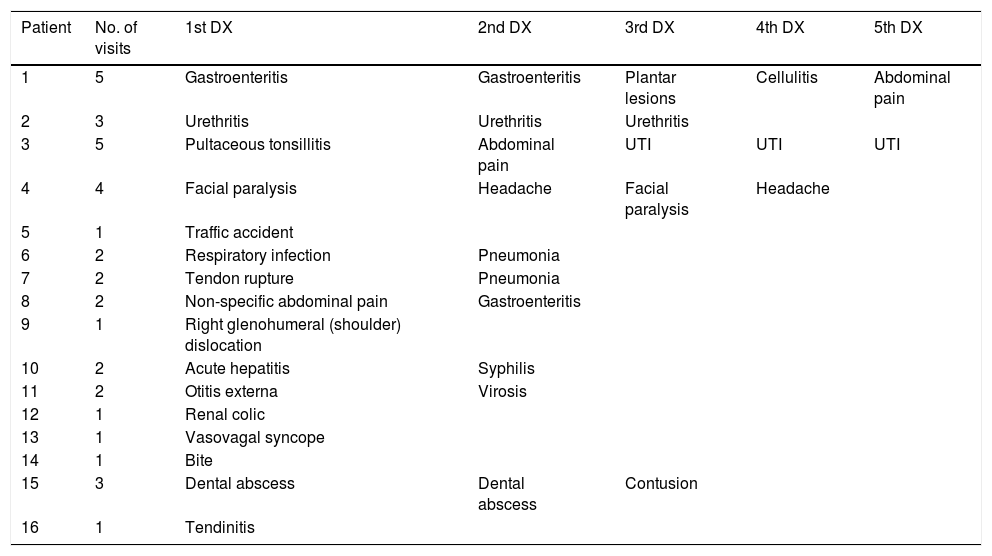

Thirteen (21.3%) patients were diagnosed during the first contact with the hospital, five in the emergency department, during an episode of facial herpes,1 respiratory infection,1 pneumonia1 or sexually transmitted infection.2 All others were diagnosed during hospitalisation for the following conditions: cerebral space-occupying lesions (SOLs),2 pneumonia,3 kidney failure,1 urinary sepsis1 or stroke.1 Another 16 (26.2%) patients were diagnosed on an outpatient basis, despite having visited the emergency department on several occasions. Table 1 shows for each patient the number of visits and the main diagnosis for the event. Yet another two (3.2%) patients were diagnosed during a second visit to the emergency department due to a cerebral SOL or pneumonia; each had been assessed on a previous occasion, due to an ulcer or lumbosciatica. As can be seen, the diseases for which the patients sought care varied widely.

Reasons for seeking care in patients with hospital contact in the 5 years prior to HIV diagnosis.

| Patient | No. of visits | 1st DX | 2nd DX | 3rd DX | 4th DX | 5th DX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | Gastroenteritis | Gastroenteritis | Plantar lesions | Cellulitis | Abdominal pain |

| 2 | 3 | Urethritis | Urethritis | Urethritis | ||

| 3 | 5 | Pultaceous tonsillitis | Abdominal pain | UTI | UTI | UTI |

| 4 | 4 | Facial paralysis | Headache | Facial paralysis | Headache | |

| 5 | 1 | Traffic accident | ||||

| 6 | 2 | Respiratory infection | Pneumonia | |||

| 7 | 2 | Tendon rupture | Pneumonia | |||

| 8 | 2 | Non-specific abdominal pain | Gastroenteritis | |||

| 9 | 1 | Right glenohumeral (shoulder) dislocation | ||||

| 10 | 2 | Acute hepatitis | Syphilis | |||

| 11 | 2 | Otitis externa | Virosis | |||

| 12 | 1 | Renal colic | ||||

| 13 | 1 | Vasovagal syncope | ||||

| 14 | 1 | Bite | ||||

| 15 | 3 | Dental abscess | Dental abscess | Contusion | ||

| 16 | 1 | Tendinitis |

DX: diagnosis; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; UTI: urinary tract infection.

In conclusion, we ought to avoid missed opportunities in contact with these patients with a view to diagnosing HIV early, developing studies that clarify in which population HIV serology should be ordered and improving rates of occult and late diagnosis. A study analysing all of the above-mentioned factors in the HIV-positive population affected by stroke could lead to recommendation or non-recommendation of screening of all or a subgroup of patients affected by this condition.

FundingThe authors declare that they did not receive any funding for the conduct of this study.

Please cite this article as: Orviz E, Suárez-Robles M, Jerez-Fernández P, Fernández-Revaldería M. Cribado para la detección del VIH y su posible implicación en los pacientes con ictus. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:338–340.