56-year-old male patient with a history of high blood pressure under treatment, computer scientist by profession, worker in a factory office. He consults the primary care emergency department for the appearance of a painful and erythematous lesion on the left upper limb, which was related to an insect bite. He denies previous contact with rural areas or animals, he only reports growing roses at home. Oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids are prescribed and antibiotic therapy with cloxacillin 500 mg/8 h per os (po) is started. He presents with progression of the lesion in 48 h, so he consults again on an outpatient basis and treatment is changed to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 500 mg/8 h po.

Given the persistence of the picture after 4 days of treatment, as well as the appearance of fever 38 °C and chills, he attends the emergency department where a lymphangitic cord is observed on the inside of the left arm as well as painful unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy. Blood cultures are extracted, a chest radiograph is performed that shows no abnormalities, and an ultrasound scan shows accumulation of subcutaneous fluid with long polylobed morphology, 33 mm in length, with signs of surrounding cellulitis. It is decided to start amoxicillin-clavulanic acid 1 g/8 h intravenously (IV) and to admit the patient to monitor further evolution. During admission, he remains afebrile with some clinical improvement, so after 3 days the treatment is transferred to po and he is discharged.

After 7 days, he is readmitted for progression of the lesion with the appearance of 3 new fluctuating inflammatory lesions following the same lymphangitic path (Fig. 1), with no fever and lab tests 19,600 leukocytes/L, 87% neutrophils and normal C reactive protein, without other alterations. Once assessed by Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology, debridement of the lesions is performed with the outflow of abundant intense yellowish pus. Antibiotic treatment is changed to ceftriaxone 1 g/24 h and linezolid 600 mg/12 h IV covering microorganisms from the skin flora such as group A beta-haemolytic streptococci and staphylococci, in addition to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus due to torpid progression. Other aetiologies that were considered, although less likely in this case, were sporotrichosis, given the history of rose care, cutaneous nocardiosis, or cutaneous non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis, although the epidemiological history did not support this. In the following days, he presents with progressive improvement in local inflammatory signs and normalised leukocytosis. 10 days after admission and at discharge, the result of the abscess culture is obtained, which showed growth of Nocardia brasiliensis (N. brasiliensis). He is then diagnosed with primary lymphocutaneous nocardiosis, the treatment being changed to co-trimoxazole 160/800 mg/8 h po. The subsequent antibiogram confirmed susceptibility to amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, 3rd generation cephalosporins, moxifloxacin, linezolid, and co-trimoxazole.

OutcomesDuring outpatient follow-up, a cranial nuclear magnetic resonance (MRI) is conducted, which rules out the presence of lesions in the central nervous system (CNS). He completes a 3-month antibiotic course with complete resolution of inflammatory signs and complete healing of surgical wounds (Fig. 2) so it is decided to end treatment. A month after finishing treatment, the patient is still asymptomatic.

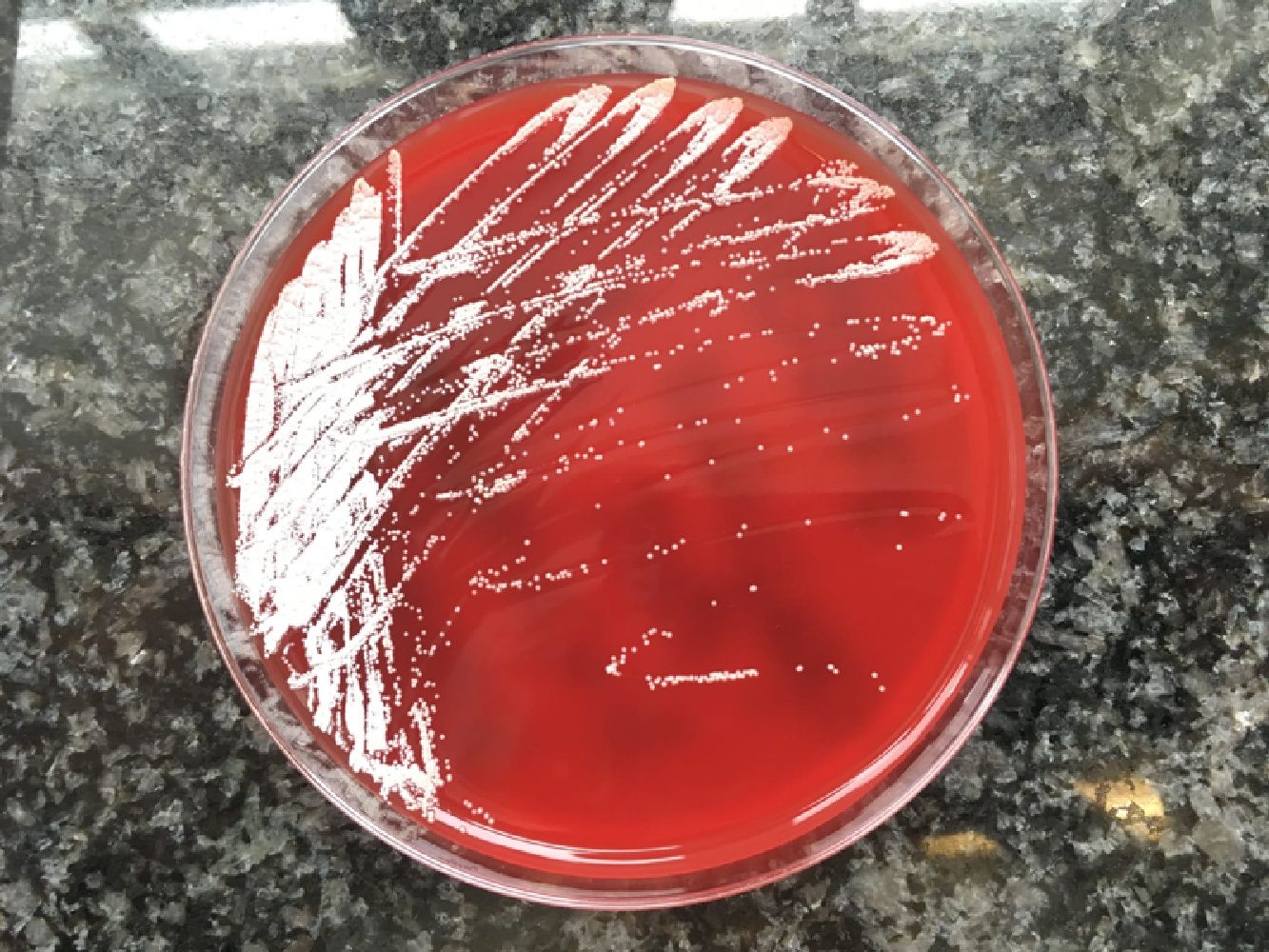

Final comment/discussionNocardiosis is a disease caused by Nocardia spp. Skin involvement due to the infection may be secondary to a disseminated infection, a condition that usually occurs in immunocompromised patients, or it can be primary (primary cutaneous nocardiosis), more frequent in immunocompetent patients due to innoculation after trauma and contamination with soil.1,2 Cutaneous nocardiosis has different forms of manifestation: superficial nocardiosis, mycetoma or lymphocutaneous nocardiosis. The latter consists of the appearance of multiple nodules following the path of a lymphatic vessel (sporotrichoid distribution) that abscess and can drain purulent material spontaneously or after debridement.3,4 It is common for the patient to report a history of plant handling, contact with animals, an insect bite or a prior fall. The species most frequently implicated in primary cutaneous nocardiosis is N. brasiliensis, as in our case, although N. asteroides and N. otitidiscaviarum were also isolated. The presumptive diagnosis is given by the visualisation of thin and branched gram-positive bacilli in the Gram stain or by staining for acid-alcohol fast bacilli, while the confirmatory diagnosis will be obtained by culture in conventional enriched media, usually in 5–7 days. Molecular biology techniques can give an earlier diagnosis, although they are not widely used. They can also be used for species identification.3,5 The morphology of the colonies will vary depending on the species, and in the case of N. brasiliensis it typically acquires a yellowish colour, similar to that of our patient (Fig. 3).6 Although cases of resolution have been described after drainage, which is essential when there are purulent collections of significant size, antibiotics with co-trimoxazole or alternatives (linezolid, minocycline, cephalosporins, imipenem, tigecycline) are usually required for a period of up to 3–4 months, depending on the extent of the clinical picture. It is recommended that a cranial MRI be performed in the diagnosis of extracranial nocardiosis to rule out the presence of CNS lesions,1 although this involvement is very rare in primary cutaneous nocardiosis and its indication is left to clinical judgement. Since it is a characteristic picture of immunocompetent patients, the search for causes of immunosuppression beyond the usual does not seem necessary.

Please cite this article as: Fafián P, Carreras-Castañer A, Rubio SC, Gomila A. Múltiples abscesos arrosariados en el brazo en un paciente inmunocompetente. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2020;38:444–445.