The case report is that of a 38-year old male patient from Morocco who has been living in Gran Canaria for the past 11 years. The patient has no allergies or other medical history of interest, except for having undergone surgery to remove the turbinates to relieve nasal obstruction in 2004.

In 2011, the patient visited our centre complaining of nasal speech and difficulty breathing, with repeated epistaxis and rhinorrhoea. A biopsy of the right nasal cavity was performed, which revealed ulcerated fragments of nasal mucosa with non-specific chronic inflammation. The presence of alcohol/acid-fast microorganisms and fungi was ruled out. Computed tomography (CT scan) images showed a polypoid mass occupying the middle and inferior turbinates of the right nasal cavity, with obliteration of the internal, middle and inferior meatus. Secondary to this was signs of mucosal thickening and air-fluid levels in the right maxillary sinus and erosion of bone structures. At this time the patient was diagnosed with bilateral nasal polyposis and signs of secondary chronic sinusitis.

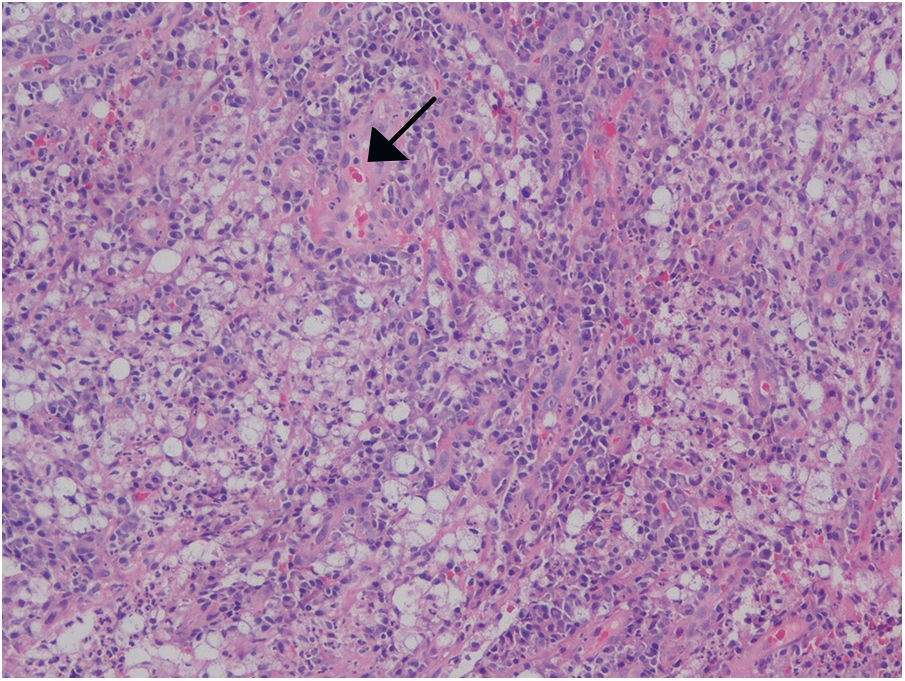

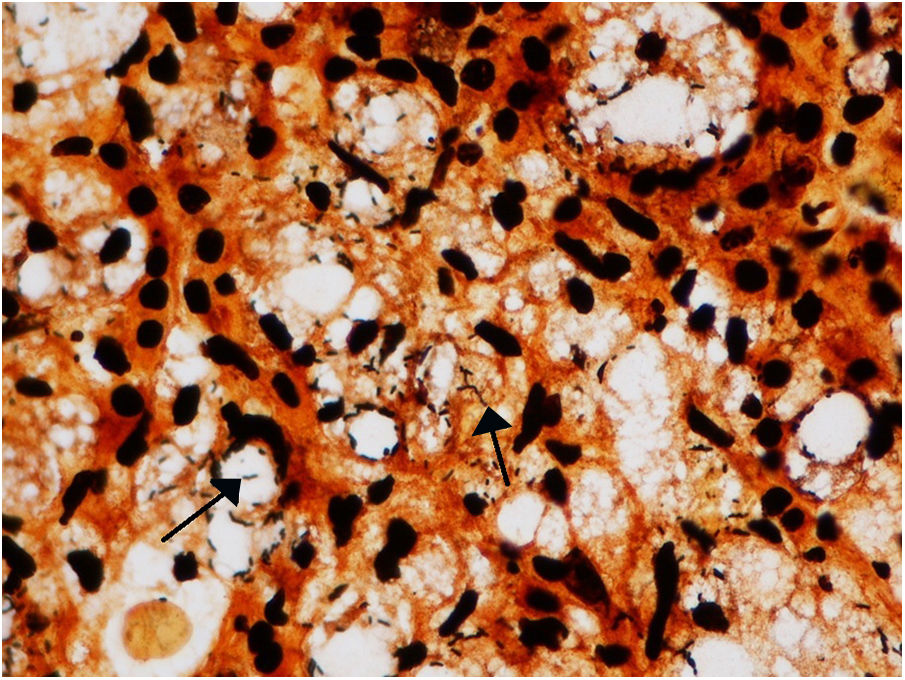

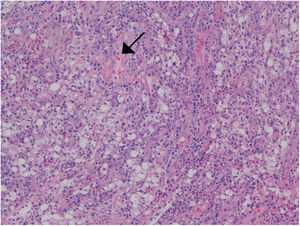

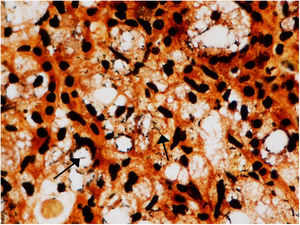

In 2016, the patient visited the centre again due to worsening of his nasal obstruction. Excisional biopsies were performed in both nasal cavities, which revealed mucosal fragments with acute and chronic xanthogranulomatous inflammation associated with intracytoplasmic bacilli, suggestive of rhinoscleroma. Such bacilli were observed in haematoxylin and eosin and Warthin–Starry stains (Figs. 1 and 2), while Ziehl-Neelsen, Grocott and S100 stains were negative.

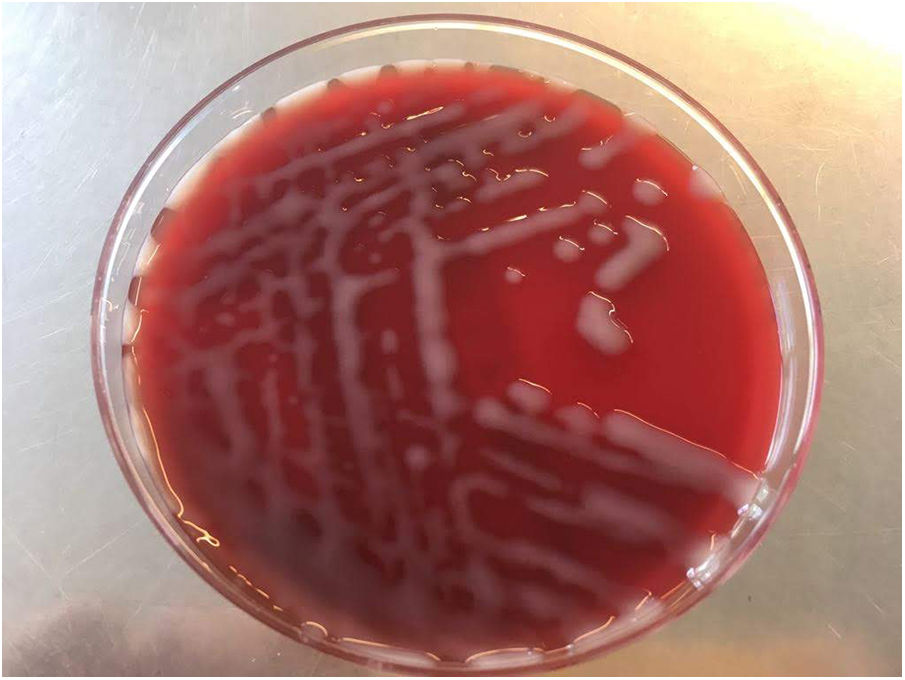

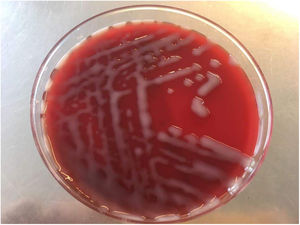

In view of the histopathology results, the biopsies taken were sent for microbiological culture. They were streaked over the usual media, and after 24h of incubation, growth of very sticky, glossy, catalase-positive and oxidase-negative colonies was observed. Gram-negative bacilli were observed on the Gram stain, which, after growth on MacConkey agar and blood agar, were identified as Klebsiellapneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae using MALDI-TOF® mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics) (Fig. 3). On suspecting that the isolate would be K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis, the strain was sent to the National Centre of Microbiology (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Majadahonda, Madrid), where molecular characterisation was carried out using sequence analysis. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests were performed using microdilution (MicroScan WalkAway® panels, Siemens), with the following results: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (MIC≤8/4mg/l, susceptible), cefuroxime (MIC≤4mg/l, susceptible), gentamicin (MIC≤2mg/l, susceptible), ciprofloxacin (MIC≤0.5mg/l, susceptible), levofloxacin (MIC≤1mg/l, susceptible), tetracycline (MIC≤4mg/l, susceptible), minocycline (MIC≤4mg/l, susceptible), fosfomycin (MIC≤32mg/l, susceptible) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (MIC≤2/38mg/l, susceptible).

After diagnosing rhinoscleroma, a CT scan of the neck and lungs was performed to rule out laryngeal and pulmonary disease. Treatment was started with minocycline 100mg/12h and ciprofloxacin 750mg/12h and the patient's progress was reassessed by endoscopy every 3 months until complete resolution of the lesions was confirmed at 9 months.

Clinical outcomeOur patient reported slight worsening of discomfort in his left nasal cavity. The possibility of resecting the infectious polyps was therefore considered in order to improve the effectiveness of antimicrobial treatment and reduce the risk of relapse. However, given our patient's gradual improvement, more surgery was not considered necessary. To date, the patient has had a favourable outcome, with no recurrence of the inflammatory mass, good nasal ventilation and no hyposmia or epistaxis.

Final commentsK. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis is a gram-negative bacillus that has an affinity for nasal mucosa. It is responsible for rhinoscleroma, a slowly progressive, chronic granulomatous infectious disease that is mainly transmitted by means of direct inhalation of droplets and contact with contaminated material.1 This infection, which is endemic in areas of the Middle East, the Americas, Eastern Europe and Indonesia, is generally associated with crowded conditions, poor hygiene and malnutrition,2,3 although the host's immunity is considered a determining factor in the pathogenesis of the disease.1–3

The infection starts in the subepithelium of the nasal mucosa, spreading from there to adjacent structures.1,4 The nose is the most affected part in 95–100% of cases, although other areas of the lower respiratory tract may also be involved less frequently.1,4,5 The disease is characterised by 3 phases or stages: catarrhal or rhinitic, granulomatous or proliferative, and sclerotic or cicatricial.1,2 Histopathology showed the presence of intracytoplasmic bacilli1 (Fig. 2). However, it is necessary to take into consideration that the pathognomonic forms (large Mikulicz cells), which are abundant in the second proliferative phase of the disease, may be absent in the initial and sclerotic phases.2,6

Due to similarities between the biochemical profiles of Klebsiella spp. and the high sequence homology that exists between the 3 subspecies of K. pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae subsp. pneumoniae, K. pneumoniae subsp. ozaenae and K. pneumoniae subsp. rhinoscleromatis), identification of the latter subspecies is very complicated and therefore different molecular methods have been developed to confirm its identification. Such methods include the detection of the capsular type 3 (K3) serotype and the study of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the phosphorine E phoE gene.6

Various studies have shown the efficacy of tetracycline and fluoroquinolone therapy1,4 and the importance of early multidisciplinary diagnosis with long-term antibiotic therapy to prevent relapse and cicatricial fibrotic sequelae7 since it is a slowly progressive, chronic disease that is difficult to cure.

FundingThe authors declare that they did not receive funding to complete this study.

We would like to thank Dr. Juan Antonio Sáez Nieto from the National Centre of Microbiology (Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Majadahonda, Madrid) for his help in characterising the microorganism.

Please cite this article as: Bastón-Paz N, Hernández-Cabrera M, Camacho-García MC, Bolaños-Rivero M. Obstrucción nasal en paciente marroquí. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2019;37:542–543.