The indicators of the pandemic have been based on the total number of diagnosed cases of COVID-19, the number of people hospitalized or in intensive care units, and deaths from the infection. The aim of this study is to describe the available data on diagnostic tests, health service used for the diagnosis of COVID-19, case detection and monitoring.

MethodDescriptive study with review of official data available on the websites of the Spanish health councils corresponding to 17 Autonomous Communities, 2 Autonomous cities and the Ministry of Health. The variables collected refer to contact tracing, technics for diagnosis, use of health services and follow-up.

ResultsAll regions of Spain show data on diagnosed cases of COVID-19 and deaths. Hospitalized cases and intensive care admissions are shown in all regions except the Balearic Islands. Diagnostic tests for COVID-19 have been registered in all regions except Madrid region and Extremadura, with scarcely information on what type of test has been performed (present in 7 CCAA), requesting service and study of contacts.

ConclusionsThe information available on the official websites of the Health Departments of the different regions of Spain are heterogeneous. Data from the use of health service or workload in Primary Care, Emergency department or Out of hours services are almost non-existent.

Los indicadores del estado de pandemia se han basado en el número total de casos diagnosticados de la COVID-19, el número de personas hospitalizadas o en unidades de cuidados intensivos y los fallecimientos por la infección. El objetivo de este estudio es describir los datos disponibles sobre pruebas diagnósticas, servicio sanitario utilizado para el diagnóstico de COVID-19 y seguimiento/detección de casos.

MétodoEstudio descriptivo con revisión de datos oficiales disponibles en las páginas web de las consejerías de sanidad de España correspondientes a 17 Comunidades Autónomas (CCAA), 2 ciudades Autónomas y el Ministerio de Sanidad. Las variables recogidas hacen referencia al estudio de contactos, diagnóstico de casos, uso de servicios sanitarios y seguimiento.

ResultadosTodas las regiones de España muestran datos de los casos diagnosticados de COVID-19 y fallecidos. Los casos hospitalizados e ingresos en cuidados intensivos se muestran en todas las regiones excepto Baleares. Las pruebas diagnósticas de COVID-19 se han registrado en todas las regiones excepto Comunidad de Madrid y Extremadura, habiendo poca información sobre qué tipo de prueba se ha realizado (presente en 7 CCAA), servicio peticionario y estudio de contactos.

ConclusionesLa información disponible en las páginas web oficiales de las Consejerías de Sanidad de las diferentes regiones de España son heterogéneas. Los datos sobre el uso o carga laboral a nivel de Atención Primaria o Servicios de urgencias hospitalarios y extrahospitalarios son cuasi inexistentes.

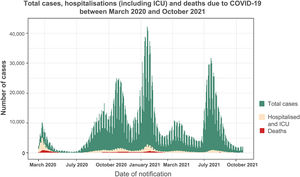

COVID-19 has affected more than 271 million people worldwide, more than 5 million of them living in Spain as of the end of December 20211. COVID-19 symptoms are mild in more than 80% of cases, while around 14% of patients are admitted, 5% of whom require intensive care, with a mortality rate of around 2.3%2. In March 2020, when the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic began in Spain, the health system collapsed in the autonomous communities (ACs) with a high incidence of cases3,4. Most of the resources were dedicated to a single disease, COVID-19, with all other healthcare activities suspended, except for essential processes (obstetric care, oncological processes, haemodialysis and childhood vaccination). The impact of the pandemic has not only been seen in care for COVID-19, but also in the decrease in other diagnoses and follow-up of chronic conditions that have taken a backseat during the waves of the pandemic5–10.

In the area of Public Health (PH) surveillance, the declared cases of COVID-19 are obtained from the individualised information from the ACs to the Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica (RENAVE) [National Epidemiological Surveillance Network], with the Ministry of Health coordinating the response with multiple international organisations such as the European Union and the World Health Organization11. In preparation for the A/H5N1 flu, the Ministry of Health reviewed the pandemic response plan12. In this plan, surveillance is described as having the main objective of providing information on “the characteristics of the infection in the population, monitoring of the evolution of the disease and the impact on health services.” The system then made it compulsory to notify the onset of symptoms, the need for hospital admission and/or death, together with other epidemiological data13. The availability of free access to databases accelerates research on the health of populations and allows early decisions to be made in the field of PH14. In turn, having freely accessible information is considered a criterion of good governance to allow citizens to make informed decisions about the management of health processes15. In COVID-19, health information systems collect diagnosed cases, the impact on hospitals and intensive care units (ICUs), adding, in addition to these factors, the type of symptoms and excess mortality. Although epidemiology surveillance systems existed in Spain, the collection and analysis of information was not optimal in some regions, with a slow response due to the lack of interoperability between the different information systems16. Despite this, in Spain the published information on the pandemic partially reflects the work of the public health (PH) system. Primary care (PC) activity is not reflected in any follow-up, nor are other indicators of the impact of the pandemic such as neglected care processes (delayed tests, postponed procedures, etc.)17–19. Regarding non-COVID-19 care processes, there is only one official document that addresses the prioritisation of surgical processes20, but without specifying other possible criteria for prioritisation within medical diseases. For all these reasons, information is key to planning the health system's response to the pandemic21. The primary objective of this study was to describe the publicly available indicators on the diagnosis and medical care of COVID-19 both nationally and in the autonomous communities. The secondary objective was to determine the total number of cases, hospitalised cases, ICU admissions and deaths from COVID-19 in Spain.

Material and methodsThis was a descriptive study reviewing the data available from each autonomous community and from the Ministry of Health through the information sent to RENAVE and published as freely accessible data on the official websites of the health ministries of the different regions of Spain (17 ACs, two autonomous cities and the Ministry of Health) (Appendix B, Annex 1). The data were collected from 14 March 2020 to 31 October 2021. It was decided to make October 2021 the cut-off date in order to assess the data that the different institutions considered relevant in monitoring the pandemic without being influenced by the possible limitations in data collection during the peaks of the pandemic waves. The variables studied were: (i) related to COVID-19 care in the daily report (number of diagnostic tests for acute infection [DTAIs], PCR positivity ratio, place of diagnosis [PC health centre, hospital or PH test centre], follow-up of PC cases, PC home visits, contact tracing, consultations with emergency telephone services, visits to A&E, and infection in care homes), and (ii) related to the monitoring of the pandemic (total cases, hospitalised cases, ICU cases and deceased cases). In addition, an information transparency index for the autonomous communities was created based on the 14 COVID-19 indicators collected. The researchers propose three levels of transparency based on the number of indicators publicly available on the information website of the autonomous community, classified as follows: basic information (4 indicators), moderate information (5–9 indicators), optimal information (≥10 indicators). Each website consulted (Appendix B Annex 1) was reviewed by peers, verifying the information in the discordant points.

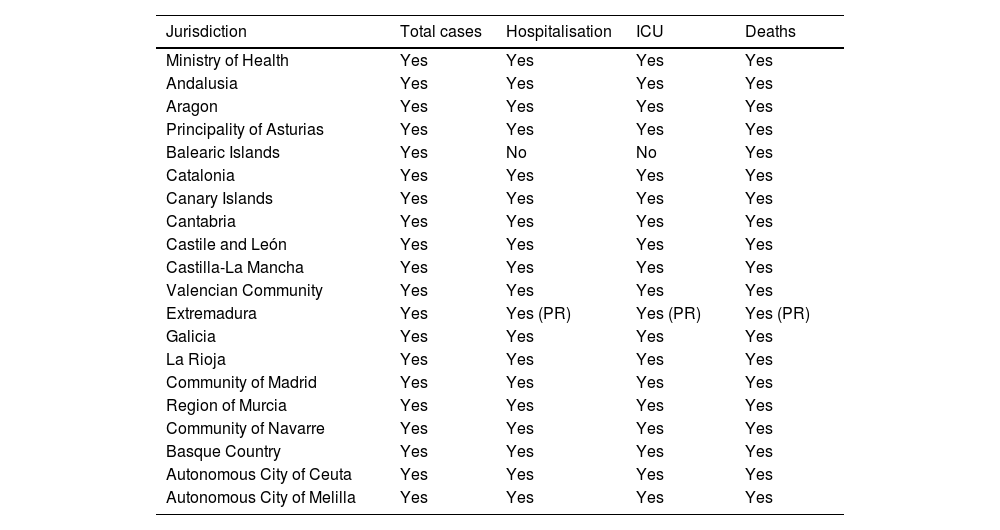

ResultsGeneral data on the pandemicAll the ACs and the daily report of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) [Carlos III Health Institute] on the pandemic offer data on the total number of cases, hospitalised cases, ICU cases and deaths, except the Balearic Islands, whose page was under construction and which does not show data on hospital/ICU admissions (Table 1).

Open data on epidemiological surveillance of the COVID-19 pandemic considered in Spain from 1 March 2020 to 31 October 2021.

| Jurisdiction | Total cases | Hospitalisation | ICU | Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Health | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Andalusia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Aragon | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Principality of Asturias | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Balearic Islands | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Catalonia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Canary Islands | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cantabria | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Castile and León | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Castilla-La Mancha | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Valencian Community | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Extremadura | Yes | Yes (PR) | Yes (PR) | Yes (PR) |

| Galicia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| La Rioja | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community of Madrid | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Region of Murcia | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Community of Navarre | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Basque Country | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Autonomous City of Ceuta | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Autonomous City of Melilla | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

ICU: intensive care unit; PR: press release.

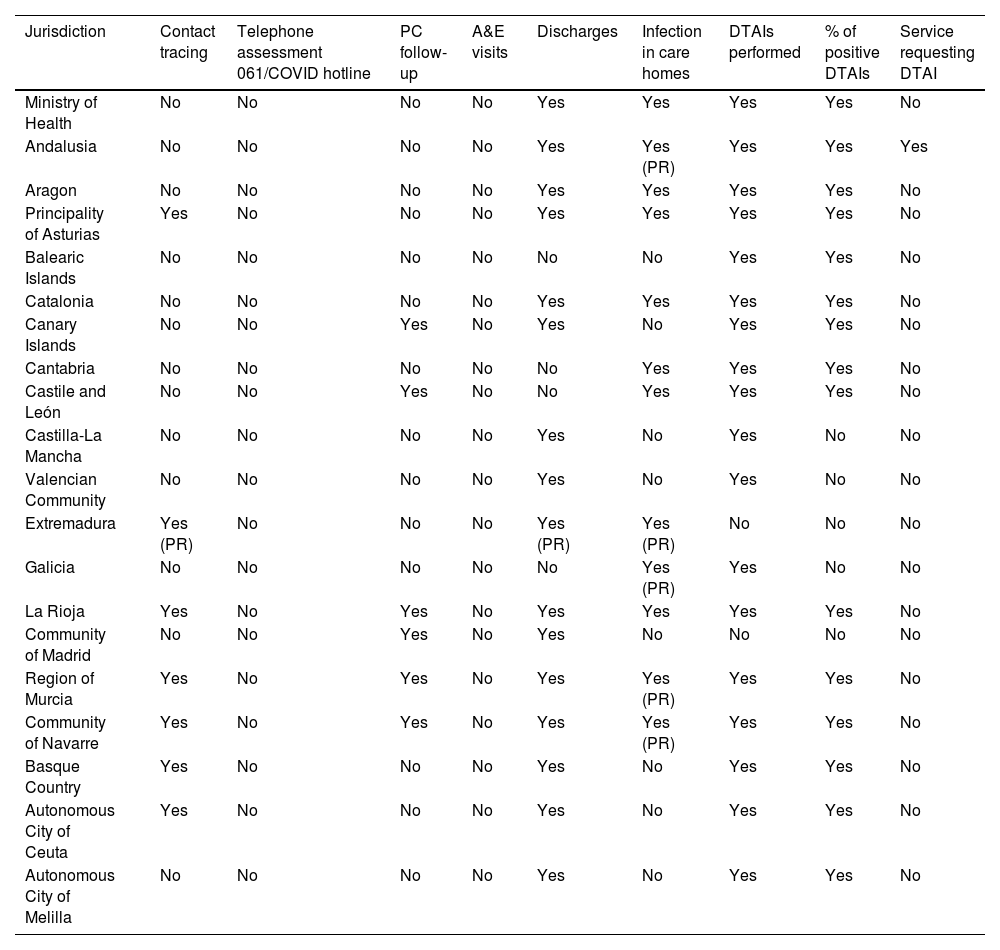

Data on diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 are collected by the ISCIII and all the ACs except Extremadura and the Community of Madrid (Table 2). The percentage of positive DTAIs is collected in 14 regions and by the Ministry of Health. However, in Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha and the Valencian Community, only positive cases by PCR are reported, while in the Balearic Islands, Castile and León, Galicia and Melilla, PCR and serological methods in addition to the antigen test are accepted. The service/department requesting the DTAI is collected in a single community, Andalusia, while contact tracing is only collected in seven ACs. The case of Castile and León is noteworthy as the number of contact tracers per province along with the minimum number of tracers according to the recommendations of the Ministry of Health (1/5000 inhabitants) are described, but the number of people traced is not specified. Information on infection in care homes is only available in four ACs as daily data. Cantabria and Castile and León also collect data on COVID-19 infection among healthcare professionals (Table 2).

Open data on the diagnosis of COVID-19 cases, tests performed and follow-up of cases on the official websites of the different regions of Spain from 1 March 2020 to 31 October 2021.

| Jurisdiction | Contact tracing | Telephone assessment 061/COVID hotline | PC follow-up | A&E visits | Discharges | Infection in care homes | DTAIs performed | % of positive DTAIs | Service requesting DTAI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ministry of Health | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Andalusia | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes (PR) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Aragon | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Principality of Asturias | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Balearic Islands | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Catalonia | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Canary Islands | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Cantabria | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Castile and León | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Castilla-La Mancha | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Valencian Community | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| Extremadura | Yes (PR) | No | No | No | Yes (PR) | Yes (PR) | No | No | No |

| Galicia | No | No | No | No | No | Yes (PR) | Yes | No | No |

| La Rioja | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Community of Madrid | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Region of Murcia | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes (PR) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Community of Navarre | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes (PR) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Basque Country | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Autonomous City of Ceuta | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Autonomous City of Melilla | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

DTAI: diagnostic test for acute infection (PCR, antigen, immunological); PC: primary care; PR: press release.

Data on care provided to cases at PC centres are collected in eight ACs (Table 2). It is worth noting the case of the Community of Navarre, which describes patients as asymptomatic, symptomatic or hospitalised.

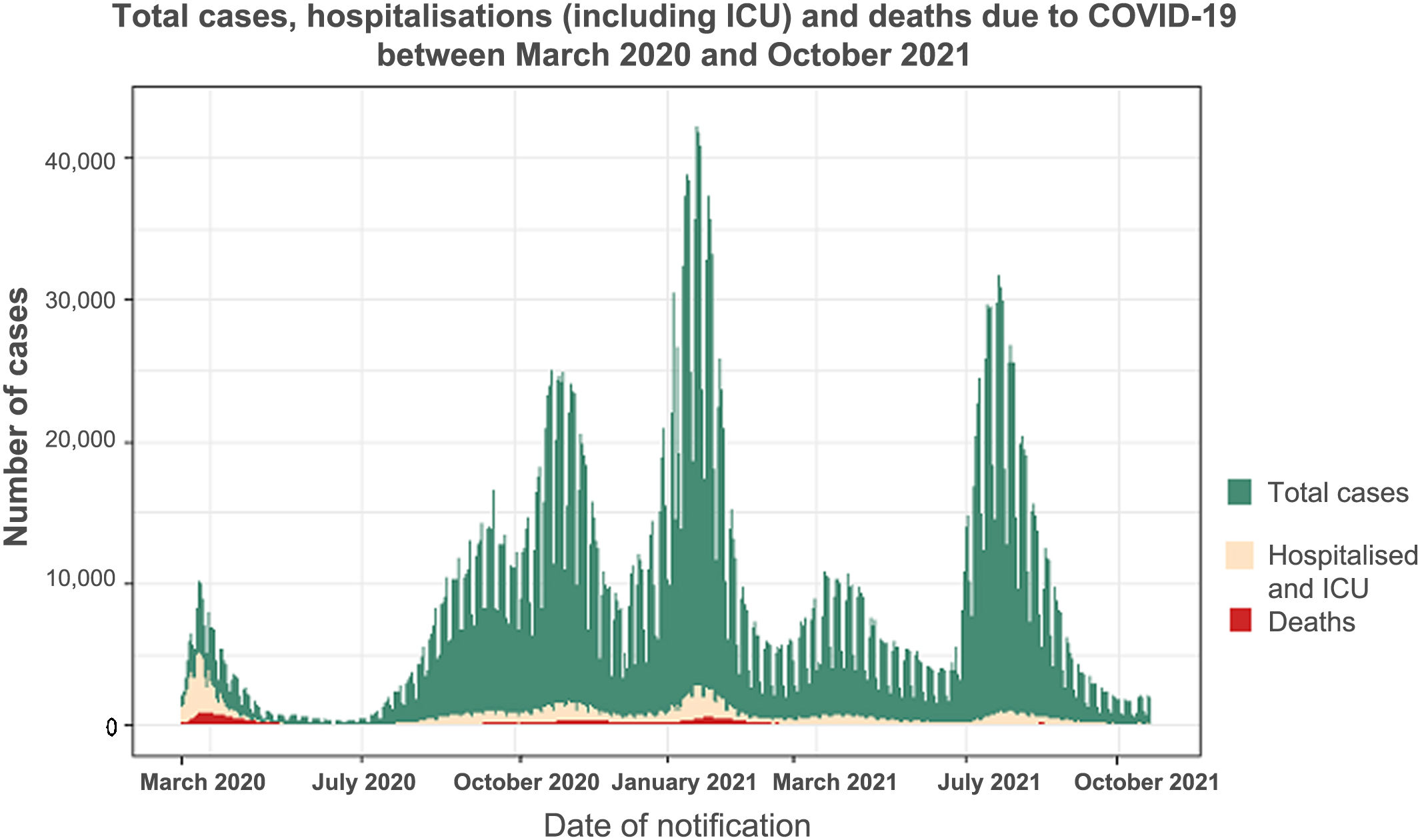

Data on COVID-19 care provided by hospital accident and emergency departments or telephone consultations (061/112) or COVID hotlines are not collected in any autonomous community or by the Ministry of Health. However, of the 4,991,117 cases reported in the study period1, the total number of cases managed by the PH, PC and hospital accident and emergency services has been estimated to be 4,477,522, which represents 89.1% of all cases (Fig. 1). This figure has been estimated by taking the total cases and subtracting the hospitalised and deceased cases. The way the health system is organised forces most patients to go to PC, PH or A&E to undergo a diagnostic test as the first place to get healthcare without requiring hospitalisation. Therefore, making a low estimate, the cases that did not require admission were eliminated to quantify the number of cases treated on an outpatient basis.

Data on medical discharges are also collected in 10 ACs and in the national report of the ISCIII. The definition of discharge is not consistent; most of the ACs record it as a hospital discharge, but Galicia, Navarre, Melilla and the Valencian Community record a discharge as the end of the “active case” (Table 2).

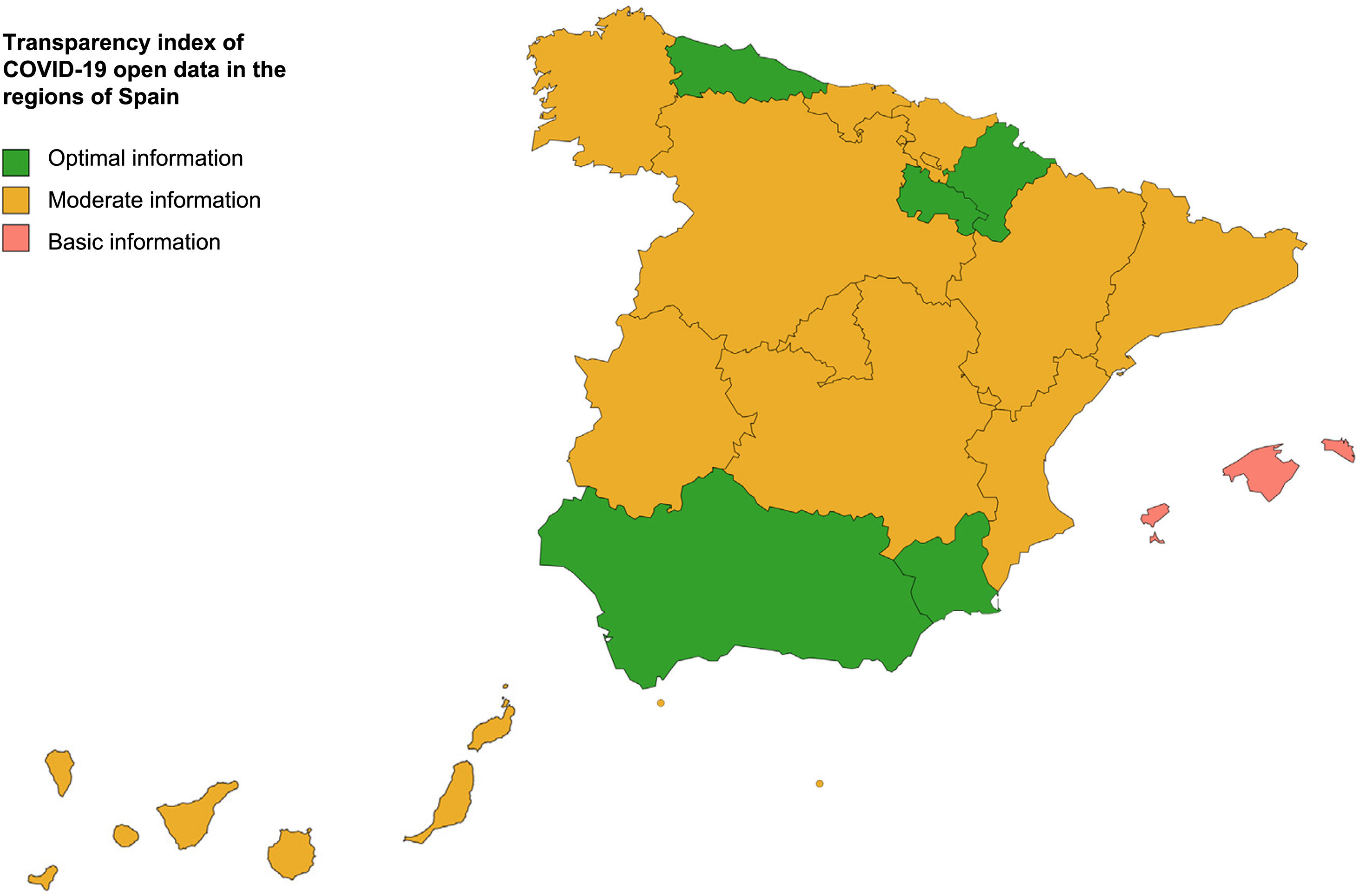

Data on the transparency indexFig. 2 shows the distribution of the transparency index regarding daily information on the pandemic. The reference website that we should consider is that of the Ministry of Health, which has a moderate transparency index as it presents eight of the 13 defined indicators. Finally, following the transparency index defined in the methods section, six ACs would present optimal data (La Rioja, Murcia, Navarre, the Basque Country, and the autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla), two regions would be classified as presenting basic information (the Balearic Islands and Galicia), with all other regions presenting adequate information.

DiscussionSummary of results that respond to the objective of the studyThe basic indicators on the total number of cases infected, hospitalised, admitted to the ICU and deceased are shown by all the ACs, except the Balearic Islands, which had its website under construction at the time of writing this manuscript. The information on active cases is available as “discharges” in 15 of the 19 regions consulted, but only six ACs specify the role of PC in caring for cases. Data on the role of PH and hospital A&E departments, as well as on care provided during outbreaks in care homes, are limited.

Interpretation of the results on the basic monitoring dataThe monitoring of infectious diseases in Spain has traditionally been carried out based on the registration of cases and mortality22. This approach may be optimal for diseases that have a marginal impact on normal activity in a health system, but it is inadequate for tackling a pandemic, as the Ministry of Health itself recognised in its plan for influenza A12. As a conclusion to this report, two more indicators were added for the epidemiological monitoring of the pandemic, which were hospitalisation in a general ward and occupancy in the ICU. In this way, the four basic epidemiological surveillance parameters indicated can be accessed in all regions of Spain, as shown by the results of this study (Table 1).

Interpretation of the results on the services usedFor optimal control of the pandemic, it is necessary to trace 80% of contacts within 48 h of diagnosis23. In Germany, in mid-May 2020, this goal was only achieved by 24% of the teams responsible for tracing, requiring the support of PC services; as in at least seven other European countries (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Estonia, France, Greece and Ukraine)24. In the case of Spain, proper epidemiological assessment and monitoring (contact tracing, tracing of active cases, early detection of cases) has been led by PH services25, requiring the collaboration of PC and hospital accident and emergency departments. Data on the work carried out by the tracing teams (contact tracing in seven of 19 regions and the follow-up carried out by PC services (six of 19 regions) are scarce on the official websites consulted, with no information on visits to hospital accident and emergency departments and the number of calls made to assess COVID-19. Despite the fact that the information referred to must be registered, in accordance with the digitalisation plan for clinical health records in Spain26, the data on the use of these services have not been made public, except for some regions, as can be seen from the results shown.

When comparing the data from Spain with those from other entities on the collection of out-of-hospital care data, Spain has provided more information than the traditional health organisations. The World Health Organization27, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC)28, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)29 and Johns Hopkins University30 do not collect data on out-of-hospital care, but instead focus on the total number of cases, the number of diagnostic tests performed and hospital/ICU occupancy. Other countries, such as Germany, Ireland and Portugal, do not collect information on outpatient care31–33. In France, data are collected through PC sentinel physicians34, using positivity for SARS-CoV-2 among all cases of respiratory infections seen in PC as an indicator. In the United Kingdom, there is no unified data collection. The National Health Service (NHS) England collects as indirect data the number of consultations in PC and A&E departments, specifying that this indicator is affected by pandemic waves, in addition to the number of telephone calls to the emergency number35–37 but without collecting specific care data. NHS Wales collects the number of consultations with suspicion of COVID-19 per 100,000 PC consultations (weekly data)38, as well as the number of calls to the emergency number for suspicion of COVID-19 (weekly data)39. The Royal College of General Practitioners together with the University of Oxford have created a tool that collects the ratio of patients with suspected COVID-19/10,000 patients in a network of health centres that care for almost eight million patients40. These data indicate that the out-of-hospital approach has not been a priority for the main agencies, although some countries do show data on this activity, so it would be feasible to collect this information. Those countries that have collected data have relied on PC electronic medical records to make use of the data in the context of the burden of disease in terms of the number of consultations, or in terms of the number of cases compared to all those with respiratory symptoms. These international indicators contrast with the national monitoring indicators for COVID-19 in PC services that have been collected by six ACs. These two approaches highlight the difficulty in measuring what happens in the outpatient care context and the need for more studies to agree on the most appropriate indicators to record this activity.

The healthcare management of the volume of COVID-19 visits has been accompanied by a neglect of other pathological processes, in prevention, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. The delay in care given to these processes could be indirect data on the evolution of the pandemic. The literature reports that 22 French hospitals recorded a decrease in admissions for appendicitis (42%), unstable angina (64%) and stroke (34%) at the most critical moments of the pandemic41. These data are consistent with data published in Spain, which demonstrate a reduction in cardiology admissions (69%)42, a decrease in kidney transplants (75%)43 and a reduction in stroke admissions (the hospitals with the most cases of COVID-19 saw a 50% reduction vs a 10% reduction in hospitals with fewer COVID-19 cases)44. Meanwhile, in Spain, a 13% decrease in the number of patients on the surgical waiting list was reported after the first wave of the pandemic45. Some of these data can be obtained through the key indicators of the National Health System prepared by the Ministry of Health46, allowing consultation on the number of surgeries, hospitalisations and the use of services or their relevance. Regarding the effect of COVID-19 on PC, in Catalonia, a decrease in follow-up of chronic conditions, vaccination and disease screening was found in the first wave of the pandemic5, with similar results in the Community of Madrid47. Thanks to the Base de Datos Clínicos de Atención Primaria (BDCAP) [Primary Care Clinical Database], some data on some chronic conditions can be compared between ACs48. These two national databases make it possible to obtain disaggregated data, but to date (September 2022), only the data for 2020 and previous years can be consulted, which limits the usefulness of this information for decision-making on the prioritisation of processes during a pandemic. This is in contrast to the UK's NHS, which reproduces retrospective data with only a two-month lag49. The British model shows that not only are data needed, but access to them can be more efficient and transparent.

Interpretation of the results on healthcare pressure (discharges, outbreaks, tests)Another point assessed in this study has been focused on the reduction of healthcare pressure defined as the information on discharges of COVID-19 cases (end of episode or illness), data that is accessible in the sources consulted. On the other hand, the work overload related to COVID-19 infections in care homes has hardly been registered, reporting the information in press releases from the sources consulted in isolation for the most part. This is not because this information is not available, since through the SERLAB laboratory results collection system a database of positive diagnostic tests for SARS-CoV-2 from public and private laboratories was obtained16. After the serious situation affecting care homes, greater transparency and disclosure of data regarding COVID-19 infections in these homes was expected50. However, the analysis of the information published by the ACs reveals that only 10 ACs have shared the information, and many of them through press releases (Andalusia, Extremadura, Galicia, the Region of Murcia and the Community of Navarre). Regarding outbreaks registered in other locations (schools, bars, gyms, etc.), only in Extremadura and Ceuta is the information on the location and number of infected people specified.

Regarding the information on diagnostic tests for active infection, the information is available in all regions except Extremadura and the Community of Madrid, defining the percentage of positivity as additional information in 14 of the 17 regions. However, only Andalusia shares information regarding the service/departments requesting the DTAI. It would again be of interest to know this information in order to detect early which services/departments may be stressed by the overload of COVID-19 care, as is being reflected in the management and forecasting of the sixth wave of the pandemic with the overwhelming of PC services51. In turn, the sale of antigen tests in pharmacies without the results being recorded detracts from the indicator on the percentage of positivity of the DTAIs, since the total number of tests carried out is lacking. There would need to be a centralised strategy to record the results of tests performed by citizens.

Interpretation of the results on the transparency indexThe absence of comparable and complete European data made PH decision-making difficult in Europe during the first weeks of the pandemic16. To assess the pandemic in Spain, there is a need for clear information that is comparable between the different ACs. One of the problems during the pandemic was that the epidemiological surveillance system was deficient and there was poor coordination between PH and other services of the health system16. The transparency index created using open data is moderate nationally and in 13 of the 19 regions defined. However, there are points for improvement that have been detailed in this discussion, with the ACs of Andalusia, the Principality of Asturias, La Rioja, the Region of Murcia and the Community of Navarre approaching the maximum score. The availability of open data is not new, and the PC database, BDCAP, describes the ACs that share all the indicators and those that only compare some data52. Other studies between ACs report similar problems when trying to compare surgical waiting lists53. Interoperability between the ACs and the central management of the Ministry of Health is essential in order to expand the evaluation indicators until they reach an optimal level throughout the country. It is also necessary for the ministry to guarantee the principles of equity, so that information is accessible not only to professionals, but also to citizens, as well as efficiency, to ensure that the data can be used to guide and improve PH decision making14.

Implications of our resultsThe inter-territorial council approved a document on how to address pandemic fatigue in December 2020, in which it recognises that “transparent, truthful, rigorous, understandable and accessible information, as well as listening to the concerns and information needs of the population, reinforce citizen confidence in the management of the crisis”54. However, these words have not been accompanied by the availability of shared indicators on the information portals of the ACs, or of the Ministry of Health. It is vitally important that the population and the political class have reliable and comparable information on the evolution of the pandemic. The workload associated with COVID-19 has not only been related to the detection of cases, contact tracing and hospital care, but also to the activity carried out by PC, PH, emergency telephone systems and accident and emergency departments. The impact of a pandemic is not comparable to other diseases that do not have the capacity to suspend all medical activity. Therefore, an exercise in indicator transparency must be carried out, collecting not only the activity of more limited key services (hospital beds and ICU), but also collecting the non-COVID-19 activity suspended due to the pandemic.

Strengths and limitationsThe information studied in this article is key when it comes to reorganising health resources in providing COVID-19 care, both to reinforce the areas of the health service with the greatest care pressure, and so that the prioritisation of patients does not delay vital care for other causes of illness not related to COVID-19.

Finally, certain limitations in the conduct of this study should be taken into account. On the one hand, the information has been extracted from open data on the official pages of the health ministries and the ISCIII, and there may be information on the specific portals for healthcare professionals that could not be accessed or recorded in the results section. With regards to outbreaks, we found that the information was reflected as an official press release or in weekly epidemiological bulletins; the latter are published a week later, making it difficult to assess the data and coordinate between PH, PC and hospital care.

The number of patients treated on an outpatient basis has been estimated based on RENAVE data. The RENAVE database is limited by the fact that there could be duplicates in data from the same week, but since the notification is individual, subsequent data cleaning should correct this situation. The calculation is limited by the fact that hospitalised and/or deceased patients may have been diagnosed on an outpatient basis and referred to the hospital, so the number of patients treated on an outpatient basis could be higher than estimated. No data were collected on where the deaths occur except in the Community of Madrid where the number of home deaths were collected. In this community, deaths outside of hospitals represent a very small number, so it can be assumed that the majority of deaths occurred in hospital.

ConclusionsThe information provided by the ACs and that published by the Ministry of Health is heterogeneous in nature. Information on total cases, hospitalisations, ICU admissions and deaths has been published by all the ACs, except the Balearic Islands, which do not report hospitalisation data. Other indicators more frequently collected by most of the ACs were: number of DTAIs performed, percentage of positive DTAIs and hospital discharges. Information such as contact tracing, PC follow-up or the action of A&E departments and emergency services is scarce and should be included in the monitoring for better management of the pandemic.

FundingThis study has not received any funding.

AuthorshipThe conceptualisation of the study was led by SAB and MPA. The data collection was carried out by the entire team, as was the interpretation of the data. Data cleaning was carried out by SAB and MGC. The first draft was written by SAB and MGC, with contributions and subsequent revisions by MPA and RGB. All the authors reviewed the final version for publication, guaranteeing the integrity of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The work carried out in relation to COVID-19 by all healthcare professionals involved in the fight against the pandemic deserves special mention. We would like to thank the members of the Eurodata project, conducted with the support of the European General Practice Research Network (EGPRN), for their help in preparing the discussion of this article.