A 54-year-old man with no personal history of note, apart from having had SARS-CoV-2 infection two weeks prior treated on an outpatient basis with only paracetamol and deflazacort 30 mg/24 h for two days, visited the accident and emergency department due to pain of sudden onset and gradual intensification in his right eye, photophobia and associated vision loss with an onset 72 h earlier. His fever spiked at 38 °C with no symptoms of bacteraemia. He denied respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary and skin- and joint-related signs and symptoms. Physical examination revealed signs of orbital congestion of the right eye with limited abduction (cranial nerve six), adduction, supraversion and infraversion with complete ptosis (cranial nerves three and four) and hypoaesthesia in the right trigeminal region (V2 and V3 dermatomes). Disappearance of the right nasolabial fold and deviation of the labial commissure were observed.

Laboratory testing revealed a mixed picture of elevated liver enzymes (aspartate aminotransferase [GOT] 106 U/l, alanine aminotransferase [GPT] 296 U/l, gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT] 789 U/l), leukocytes 14,010/mm3 with 88.7% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, C-reactive protein 14.4 mg/l, fibrinogen 746 mg/dl, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 60 mm/h and lactate dehydrogenase 516 U/l. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head without contrast showed right frontal cortical hypodensity and occupation of both maxillary sinuses by a substance with the density of soft tissue, suggestive of sinusitis. Complementary CT angiography of the supra-aortic trunks detected a right ophthalmic artery filling defect consistent with venous thrombosis. The patient was admitted with the initial suspicion of thrombosis following SARS-CoV-2 infection or large-vessel vasculitis, and empirical treatment was started with high-dose corticosteroids.

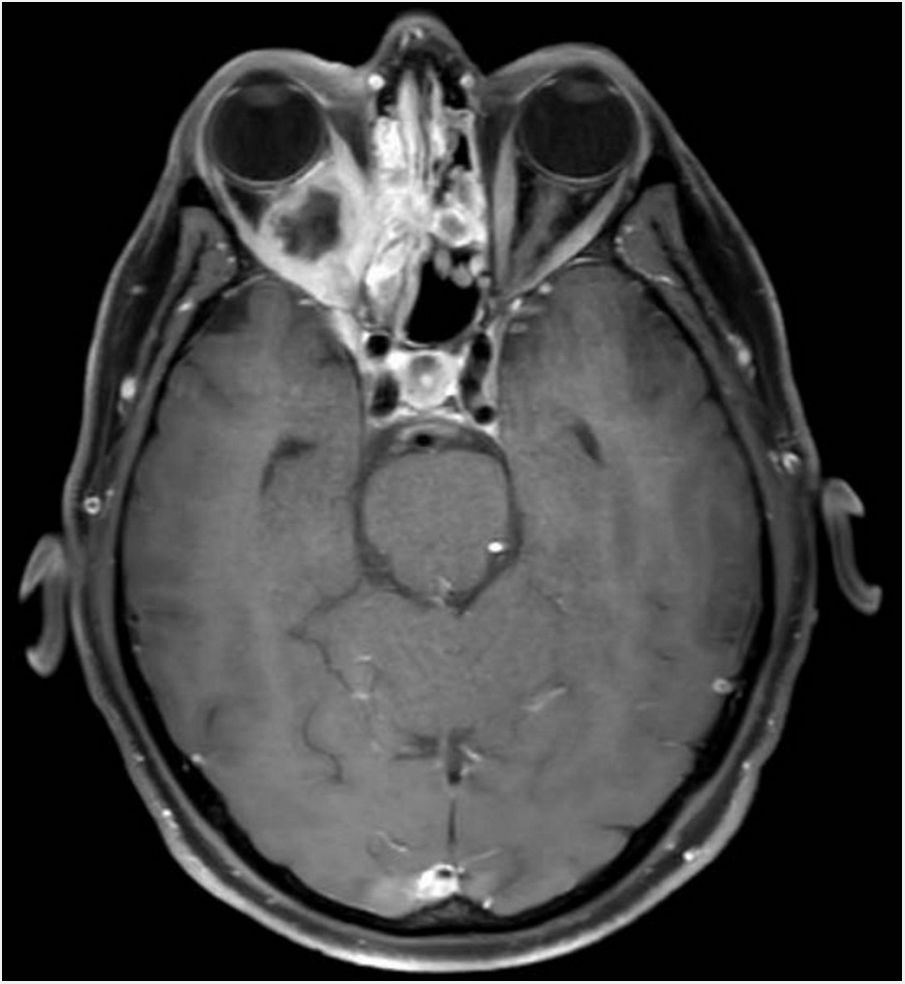

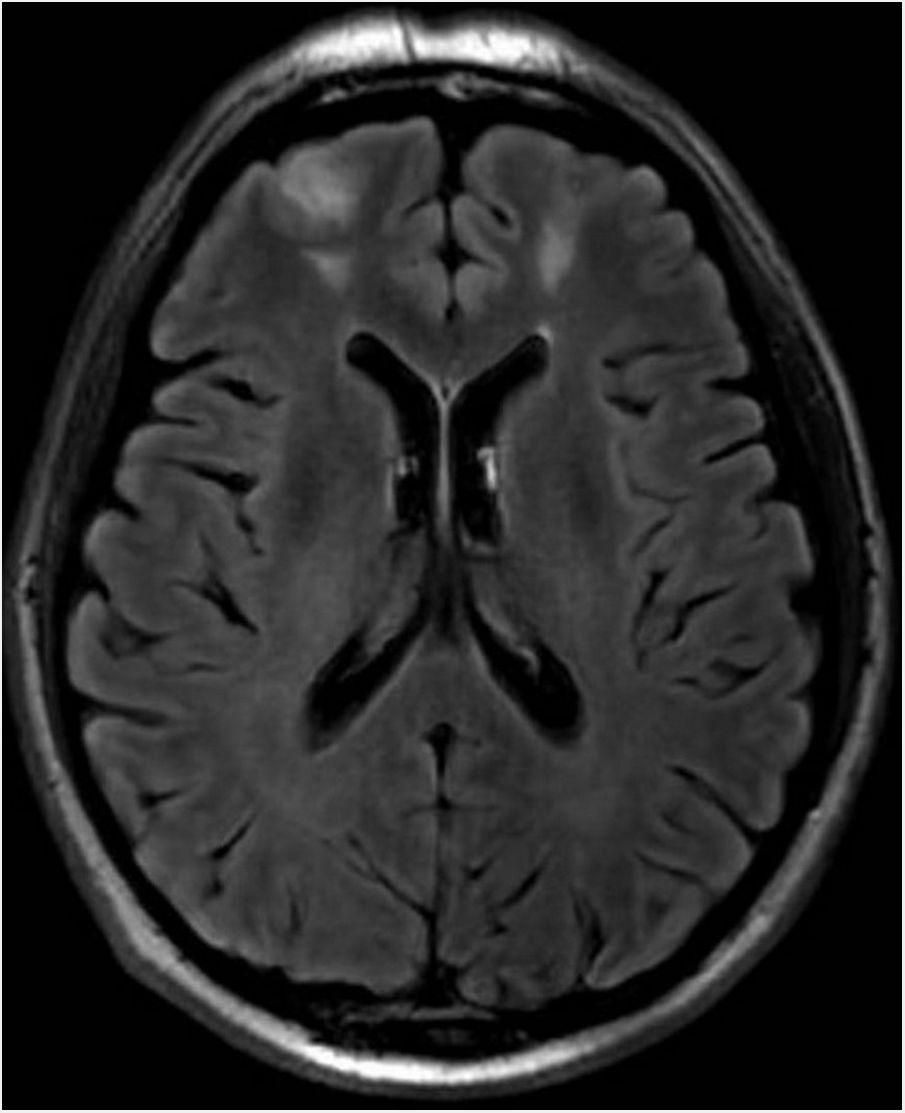

Clinical courseAn ophthalmological assessment revealed retinal oedema and pallor and a relative afferent pupillary defect in the right eye. Doppler ultrasound of the carotid and temporal arteries was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed an extensive inflammatory process of the paranasal sinu with orbital extension (Fig. 1, Image 1: T1-weighted transverse slice) and corticosubcortical ischaemic lesions in the frontal lobes in relation to possible fungal infection (Fig. 2, Image 2: FLAIR sequence) and a positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) scan confirmed intense pathological metabolic hyperuptake in the nose, septum, turbinates, nasopharynx and maxillary sinuses. Therefore, corticosteroids were suspended in the absence of findings suggestive of an vasculitic inflammatory process, and empirical antifungal treatment was started. Flexible fibrobronchoscopy was used to take samples from the right nostril for microbiological and histopathological study. Finally, microbiological isolation of Aspergillus fumigatus was achieved in all samples taken and pathology reported the presence of fragmented hyphae using Grocott’s staining. Ultimately, the patient was diagnosed with invasive rhinocerebral aspergillosis. The area was debrided by otorhinolaryngology and associated treatment with voriconazole and liposomal amphotericin B was started. Currently, the patient is on isavuconazole alone; his lesions showed radiological improvement following two months of treatment.

The genus Aspergillus, first reported in 1729 by P.A. Micheli, is ubiquitous in nature, and inhalation of conidia is a regular phenomenon. However, tissue invasion is uncommon and essentially occurs in neutropaenic patients and patients with some degree of cellular immunosuppression. The mortality rate of the invasive forms depends on the clinical form and host type. In untreated cases with central nervous system (CNS) involvement, it is up to 88%1.

Aspergillus spp. can spread beyond the respiratory tract and affect the skin, CNS, eyes and other structures. In the paranasal sinuses, it may have a similar presentation to mucormycosis. Although serious cases have been reported in immunocompetent patients2, rhinocerebral extension tends to be characteristic of patients with prolonged neutropaenia. Eye symptoms develop with orbital involvement, which might cause blurred vision, oculomotor paralysis or blindness due to central retinal artery thrombosis3. The infection can spread to the cavernous sinus and cause thrombosis thereof and extension to the central nervous system (CNS).

With respect to treatment, it is very important to measure azole levels, since voriconazole for example may take five to seven days to reach a steady state, which is not desirable in critically ill patients4. The greater diagnostic capacity and availability of the new antifungal treatments should improve the prognosis for this infection. Nevertheless, the urgency of the growing resistance to azoles could diminish some optimism, given that rates of resistance to azoles as high as 26% have been reported at some centres in European countries5.

FundingThe authors declare that they received no funding to conduct this study.

Please cite this article as: Bustos-Merlo A, Rosales-Castillo A, Sotorrío Simo V. Causa inesperada de lesiones isquémicas en paciente inmunocompetente. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:273–274.