Consumption of antibiotics is high in Spain, primarily in children. Excessive use of then contributes to the development of antimicrobial resistance. The aim of our study is to analyse the evolution of antibiotic consumption at the Primary Health Care in the paediatric population of Asturias, Spain, from 2014 to 2021, and to evaluate the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on it.

MethodsRetrospective and observational study using data about antibacterial agents for systemic use dispensed for official prescriptions to children under 14 years in Primary Care. Antibiotic consumption is expressed as defined daily dose (DDD) per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID).

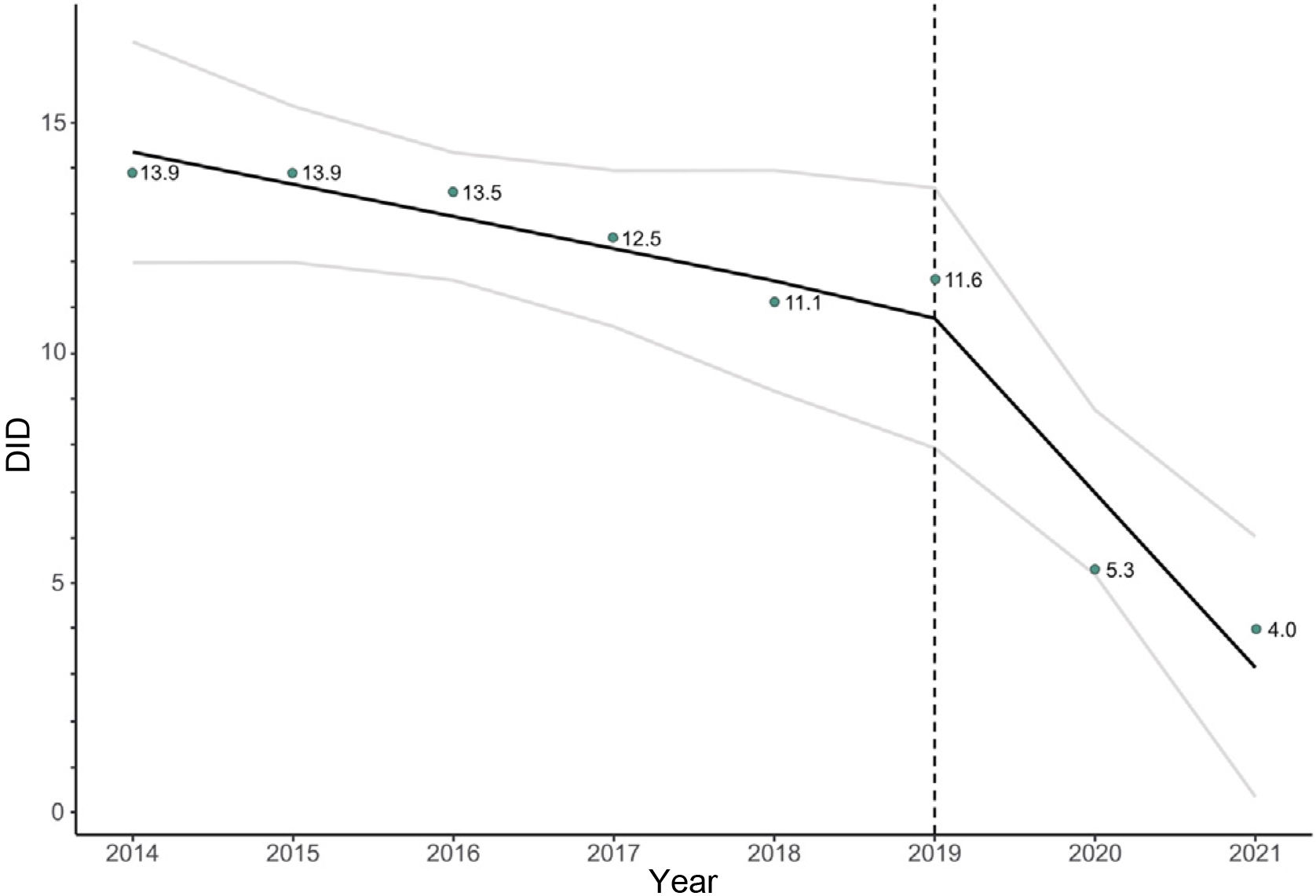

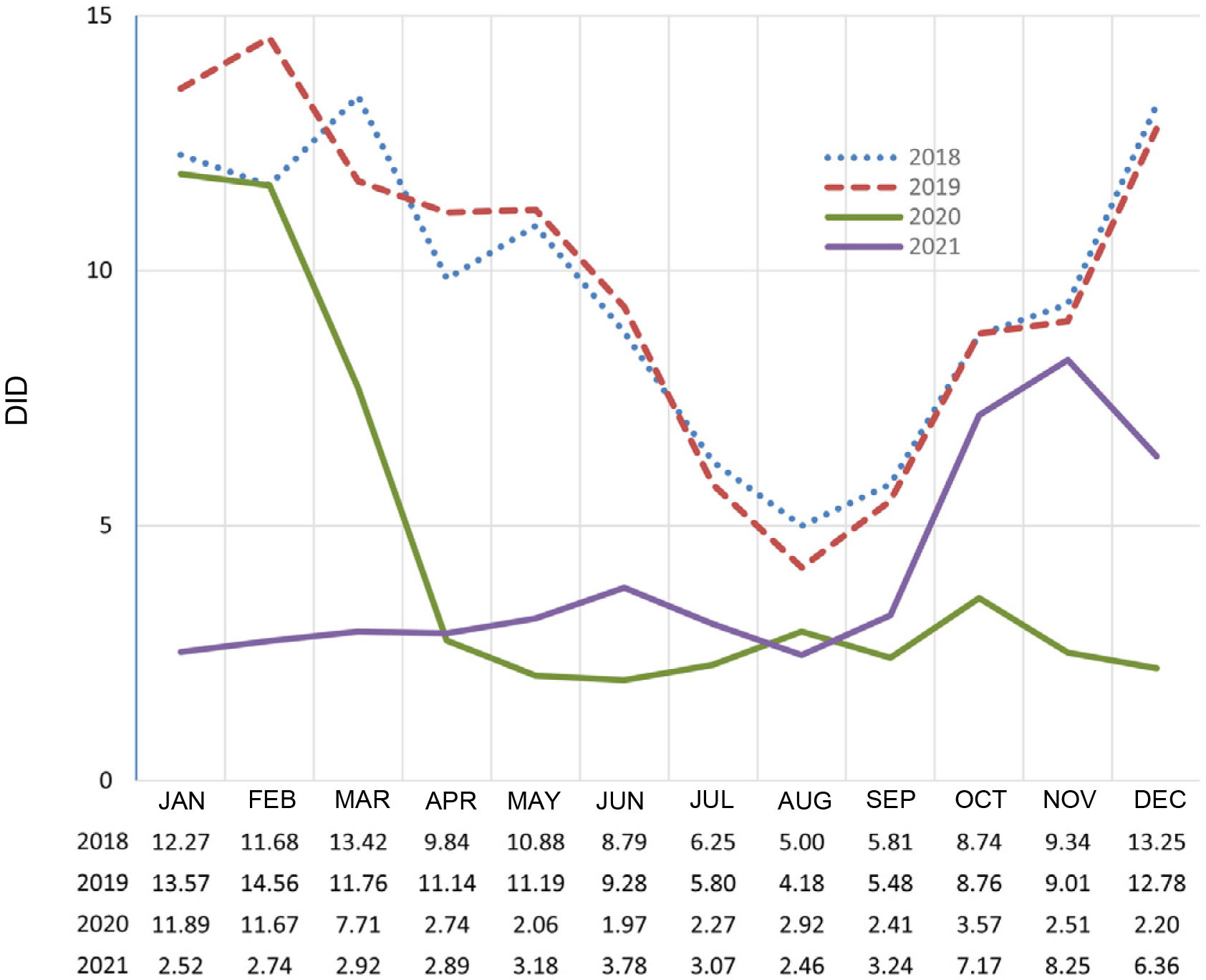

ResultsThe antibiotic consumption rate dropped from 13.9 DID in 2014 to 4.0 in 2021 (β=−1,42, p=0,002), with and inflection point in 2019. From 2019 to 2020 antibiotic use dropped by 47.1%. Antibiotic consumption remained very low from April 2020 to September 2021, and then moderately increased from October 2021. Prevalence of antibiotic use dropped from 39.9% in 2014 to 17.5% in 2021 (β=−3,64, p=0,006). Relative consumption of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid decreased, while those of amoxiciline and third-generation cephalosporins increased.

ConclusionsPaediatric antibiotic consumption collapsed in Asturias in 2020, coinciding with COVID-19 pandemic. Monitoring of antimicrobial usage indicators will allow to check if these changes are sustained over time.

En España existe un alto consumo de antibióticos, especialmente en los primeros años de vida. Un uso excesivo de antimicrobianos contribuye a la aparición de resistencias. El objetivo de este estudio es analizar la evolución del consumo de antibióticos en población pediátrica entre 2014 y 2021 en la Atención Primaria del Principado de Asturias y estudiar el impacto de la pandemia por COVID-19 sobre el mismo.

MétodosEstudio observacional y retrospectivo que recoge las prescripciones de antibacterianos para uso sistémico dispensadas a partir de recetas oficiales emitidas para pacientes menores de 14 años en Atención Primaria. Se mide el consumo en dosis diarias definidas (DDD) por 1.000 habitantes y día (DHD).

ResultadosLa tasa de consumo de antibióticos descendió desde 13,9 DHD en 2014 a 4,0 en 2021 (β=−1,42, p=0,002) con un punto de inflexión en el año 2019. Entre 2019 y 2020 el descenso fue del 47,1%. El consumo se mantuvo en niveles muy bajos entre abril de 2020 y septiembre de 2021, con un repunte contenido desde octubre de 2021. La prevalencia de uso de antibióticos cayó desde 39,9% en 2014 a 17,5% en 2021 (β=−3,64, p=0,006). Disminuyó el consumo relativo de amoxicilina-clavulánico y aumentó el de amoxicilina y cefalosporinas de tercera generación.

ConclusiónEn Asturias, el consumo pediátrico de antibióticos en Atención Primaria se desplomó a partir de 2020, coincidiendo con la COVID-19. La monitorización de estos indicadores permitirá comprobar en qué medida se mantienen los cambios en el tiempo.

Resistance to antimicrobials occurs when microorganisms undergo changes that reduce or cancel out the effectiveness of the medications used to treat the infections they cause.1 Inappropriate prescribing and improper use of antimicrobials, both in human and veterinary medicine, as well as in agriculture and the agri-food industries, increase the speed at which resistant organisms develop and spread.1

It is estimated that 90% of antibiotic use in human health is generated in primary care (PC), where a third of consultations are related to infectious diseases.2 Monitoring antibiotic consumption is considered essential to identifying the pressure their use exerts on the emergence of resistance.3

According to the Spanish Plan Nacional de Resistencia a Antibióticos (PRAN) [National Antibiotic Resistance Plan], the main problems in Spain concerning the use of antibiotics in children are4:

- 1.

High rates of consumption, especially in the under-fives. Higher than in other European countries for the same age group.

- 2.

Prescribing in non-bacterial disorders such as viral pharyngotonsillitis, bronchitis or the common cold.

- 3.

Inadequate selection of the type of antibiotic, with high rates of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid and macrolide use in disorders where they are not first choice.

To improve antibiotic prescribing and help to reduce resistance, it is important that we know how antibiotics are used, measure their use and define indicators with standards to establish their quality. As part of the PRAN, a series of indicators for antibiotic use have been selected for the paediatric population in PC.5

In June 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) expressed its fear that the trend of increasing resistance to antimicrobials would accelerate due to the inappropriate use of antibiotics during the COVID-19 pandemic.6 According to PRAN data, during the first epidemic wave of the pandemic, the rate of antibiotic consumption fell by 40% in PC and increased by 40% in hospitals.

The aim of this study was to analyse changes in some of the antibiotic consumption indicators proposed by the PRAN in the paediatric population over the last eight years (2014−2021) within the scope of PC provided by the Servicio de Salud del Principado de Asturias (SESPA) [Principality of Asturias Health Service]. We also aimed to look at whether or not the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic had any impact on antibiotic consumption in this population.

MethodsThis was a retrospective observational study where we collected all PC prescriptions for therapeutic group J01 (antibacterials for systemic use) of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification7,8 dispensed in chemists with official SESPA prescriptions for children under 14 years of age.

Consumption indicatorsData relating to the Defined Daily Doses (DDD) of antibiotics for systemic use (J01), the number of packs of this same group and the number of packs of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (subgroup J01CR02), amoxicillin (subgroup J01CA04), beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins (subgroup J01CE), macrolides (subgroup J01FA) and third-generation cephalosporins (subgroup J01DD) dispensed in any chemist in Asturias during the period January 2014 to December 2021 were collected from the Pharmacy Section of SESPA’s Sub-directorate for Infrastructure and Technical Services. Prescriptions from hospitals or health insurance companies or private prescriptions were not included.

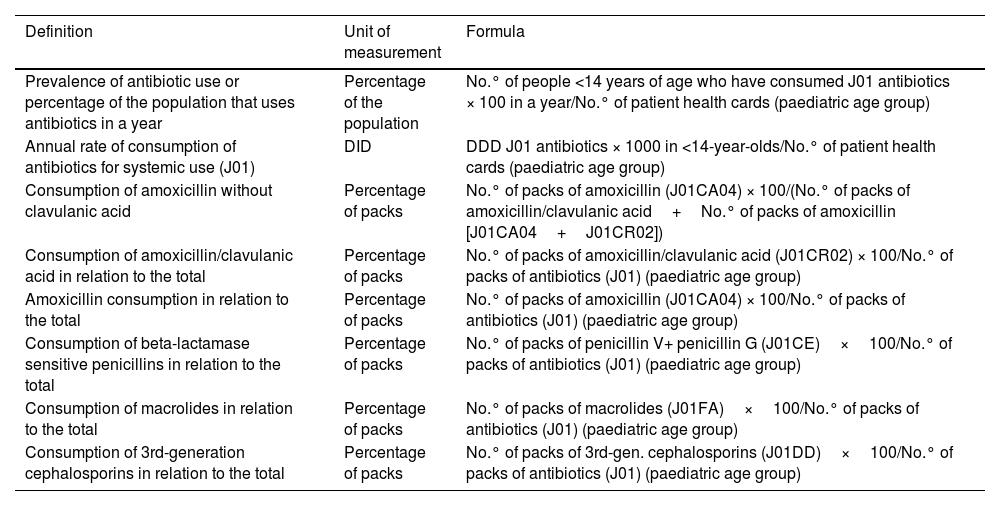

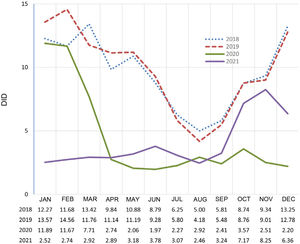

For the technical units of measurement for each of the indicators studied, we followed the PRAN recommendations, as shown in Table 1. The annual consumption rate of antibiotics for systemic use (J01) is expressed as the number of DDDs per 1000 inhabitants under the age of 14 per day (DID). The following formula was used to calculate the DDD number:

Definitions, units of measurement and formulas for the indicators of antibiotic consumption in the population under 14 years of age.

| Definition | Unit of measurement | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Prevalence of antibiotic use or percentage of the population that uses antibiotics in a year | Percentage of the population | No.° of people <14 years of age who have consumed J01 antibiotics × 100 in a year/No.° of patient health cards (paediatric age group) |

| Annual rate of consumption of antibiotics for systemic use (J01) | DID | DDD J01 antibiotics × 1000 in <14-year-olds/No.° of patient health cards (paediatric age group) |

| Consumption of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of amoxicillin (J01CA04) × 100/(No.° of packs of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid+No.° of packs of amoxicillin [J01CA04+J01CR02]) |

| Consumption of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in relation to the total | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (J01CR02) × 100/No.° of packs of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) |

| Amoxicillin consumption in relation to the total | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of amoxicillin (J01CA04) × 100/No.° of packs of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) |

| Consumption of beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins in relation to the total | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of penicillin V+ penicillin G (J01CE)×100/No.° of packs of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) |

| Consumption of macrolides in relation to the total | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of macrolides (J01FA)×100/No.° of packs of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) |

| Consumption of 3rd-generation cephalosporins in relation to the total | Percentage of packs | No.° of packs of 3rd-gen. cephalosporins (J01DD)×100/No.° of packs of antibiotics (J01) (paediatric age group) |

DDD: defined daily doses; DID: defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day.

The DDD of the denominator is the international technical unit of measurement recommended by the WHO for conducting drug use studies, and is defined as the average daily maintenance dose of a drug used for its main indication in adults and for a certain route of administration.9

For the data on the number of inhabitants, we used the population under 14 years of age with an active Tarjeta Sanitaria Individual (TSI) [Individual Health Card] in the database of the Population and Health Resources Information System (SIPRES), corresponding to the last cut-off point of the immediately preceding year (population covered by the corresponding Health Service Contract).

For the other indicators, the data were expressed as the sum of packs, percentage of packs compared to the total and percentage of the paediatric population that consumed antibiotics, grouped by year.

Statistical analysisThe statistical package R 4.1.0 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) was used for the analysis. Simple linear regression analyses were performed with the main indicators of antibiotic consumption, using the year as the independent variable. In addition, a segmented regression analysis of total antibiotic consumption was performed, considering DID as the dependent variable and the year of study as the independent variable. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias (2021.415). Waiver of informed consent was granted, as we used anonymised aggregated data.

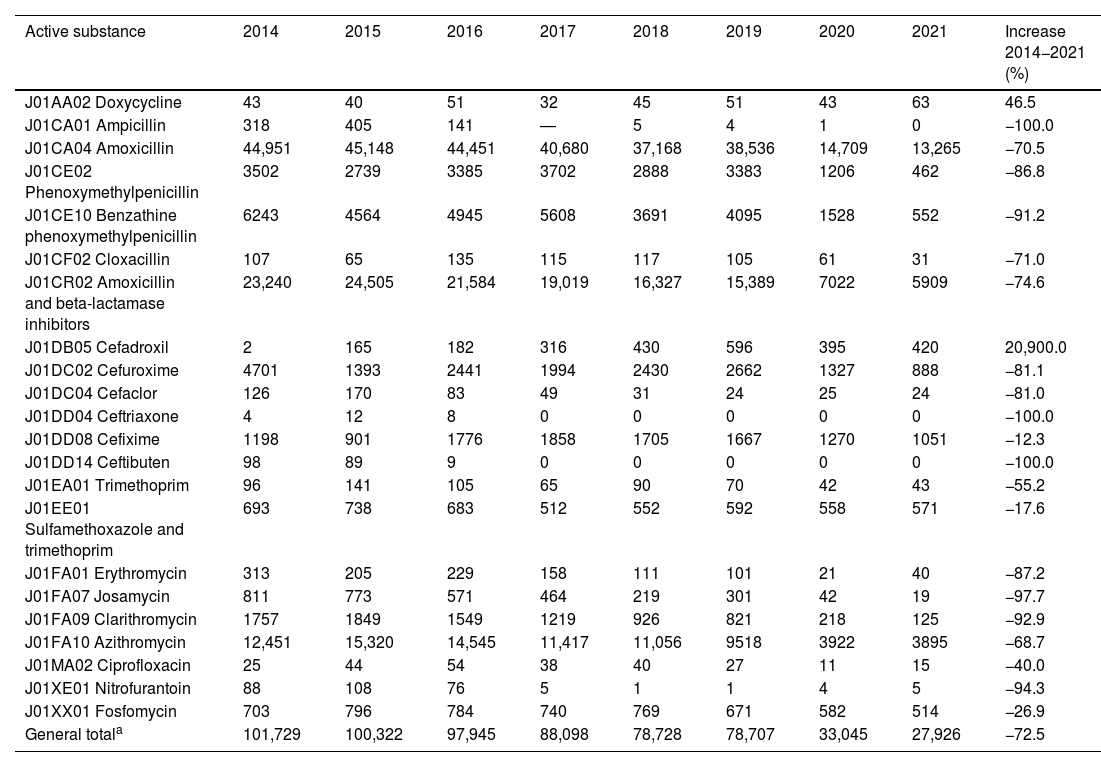

ResultsThe number of packs dispensed for each active substance is shown in Table 2. The active substance with the highest total consumption was amoxicillin (278,908 packs dispensed), followed by amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (132,995 packs). The majority trend was towards a decrease in consumption between 2014 and 2021, although there was a notable increase in the use of cefadroxil.

Sum of the packs dispensed of the main active substances of therapeutic group J01 in the paediatric population (2014–2021).

| Active substance | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Increase 2014−2021 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J01AA02 Doxycycline | 43 | 40 | 51 | 32 | 45 | 51 | 43 | 63 | 46.5 |

| J01CA01 Ampicillin | 318 | 405 | 141 | — | 5 | 4 | 1 | 0 | −100.0 |

| J01CA04 Amoxicillin | 44,951 | 45,148 | 44,451 | 40,680 | 37,168 | 38,536 | 14,709 | 13,265 | −70.5 |

| J01CE02 Phenoxymethylpenicillin | 3502 | 2739 | 3385 | 3702 | 2888 | 3383 | 1206 | 462 | −86.8 |

| J01CE10 Benzathine phenoxymethylpenicillin | 6243 | 4564 | 4945 | 5608 | 3691 | 4095 | 1528 | 552 | −91.2 |

| J01CF02 Cloxacillin | 107 | 65 | 135 | 115 | 117 | 105 | 61 | 31 | −71.0 |

| J01CR02 Amoxicillin and beta-lactamase inhibitors | 23,240 | 24,505 | 21,584 | 19,019 | 16,327 | 15,389 | 7022 | 5909 | −74.6 |

| J01DB05 Cefadroxil | 2 | 165 | 182 | 316 | 430 | 596 | 395 | 420 | 20,900.0 |

| J01DC02 Cefuroxime | 4701 | 1393 | 2441 | 1994 | 2430 | 2662 | 1327 | 888 | −81.1 |

| J01DC04 Cefaclor | 126 | 170 | 83 | 49 | 31 | 24 | 25 | 24 | −81.0 |

| J01DD04 Ceftriaxone | 4 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −100.0 |

| J01DD08 Cefixime | 1198 | 901 | 1776 | 1858 | 1705 | 1667 | 1270 | 1051 | −12.3 |

| J01DD14 Ceftibuten | 98 | 89 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −100.0 |

| J01EA01 Trimethoprim | 96 | 141 | 105 | 65 | 90 | 70 | 42 | 43 | −55.2 |

| J01EE01 Sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim | 693 | 738 | 683 | 512 | 552 | 592 | 558 | 571 | −17.6 |

| J01FA01 Erythromycin | 313 | 205 | 229 | 158 | 111 | 101 | 21 | 40 | −87.2 |

| J01FA07 Josamycin | 811 | 773 | 571 | 464 | 219 | 301 | 42 | 19 | −97.7 |

| J01FA09 Clarithromycin | 1757 | 1849 | 1549 | 1219 | 926 | 821 | 218 | 125 | −92.9 |

| J01FA10 Azithromycin | 12,451 | 15,320 | 14,545 | 11,417 | 11,056 | 9518 | 3922 | 3895 | −68.7 |

| J01MA02 Ciprofloxacin | 25 | 44 | 54 | 38 | 40 | 27 | 11 | 15 | −40.0 |

| J01XE01 Nitrofurantoin | 88 | 108 | 76 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 | −94.3 |

| J01XX01 Fosfomycin | 703 | 796 | 784 | 740 | 769 | 671 | 582 | 514 | −26.9 |

| General totala | 101,729 | 100,322 | 97,945 | 88,098 | 78,728 | 78,707 | 33,045 | 27,926 | −72.5 |

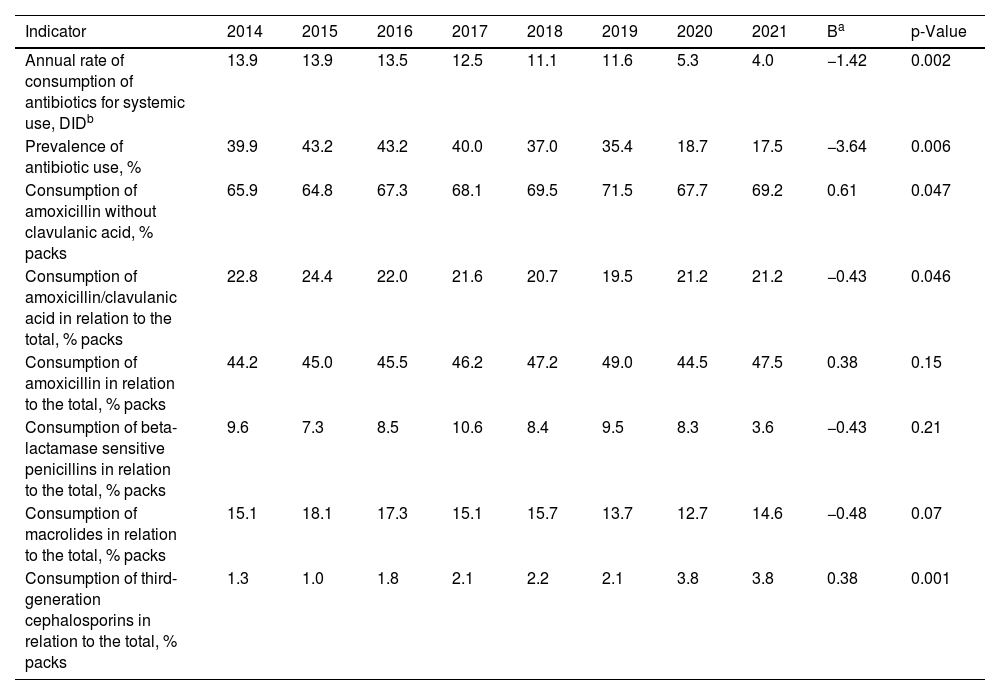

The main indicators of antibiotic consumption are shown in Table 3. In Asturias as a whole and in the PC setting, the percentage of children who consumed an antibiotic in one year compared to the total child population fell from 39.9% in 2014 to 17.5% in 2021, representing a decrease of 56.1%. The variation in the percentage of children who consumed an antibiotic compared to the total paediatric population in 2020 vs 2019 represented a decrease of 47.1%.

Changes in antibiotic consumption indicators in the paediatric population in Asturias.

| Indicator | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | Ba | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual rate of consumption of antibiotics for systemic use, DIDb | 13.9 | 13.9 | 13.5 | 12.5 | 11.1 | 11.6 | 5.3 | 4.0 | −1.42 | 0.002 |

| Prevalence of antibiotic use, % | 39.9 | 43.2 | 43.2 | 40.0 | 37.0 | 35.4 | 18.7 | 17.5 | −3.64 | 0.006 |

| Consumption of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid, % packs | 65.9 | 64.8 | 67.3 | 68.1 | 69.5 | 71.5 | 67.7 | 69.2 | 0.61 | 0.047 |

| Consumption of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid in relation to the total, % packs | 22.8 | 24.4 | 22.0 | 21.6 | 20.7 | 19.5 | 21.2 | 21.2 | −0.43 | 0.046 |

| Consumption of amoxicillin in relation to the total, % packs | 44.2 | 45.0 | 45.5 | 46.2 | 47.2 | 49.0 | 44.5 | 47.5 | 0.38 | 0.15 |

| Consumption of beta-lactamase sensitive penicillins in relation to the total, % packs | 9.6 | 7.3 | 8.5 | 10.6 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 3.6 | −0.43 | 0.21 |

| Consumption of macrolides in relation to the total, % packs | 15.1 | 18.1 | 17.3 | 15.1 | 15.7 | 13.7 | 12.7 | 14.6 | −0.48 | 0.07 |

| Consumption of third-generation cephalosporins in relation to the total, % packs | 1.3 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.1 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 0.38 | 0.001 |

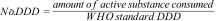

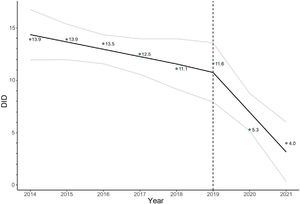

There was a considerable reduction in the annual consumption rate of antibiotics for systemic use from 13.9 DID in 2014 to 4.0 in 2021 (71.2% decrease). In the segmented regression analysis, the model that showed the best fit included a single inflection point in the year 2019 (Fig. 1). According to this model, in the first part of the time period (2014–2019) there would be a slight decrease of 0.7 DID per year (95% CI: −1.39 to −0.01), while in the second part (2019–2021) the decline would accelerate to 3.1 DID per year (95% CI: −4.8 to −1.4). On a graph, the monthly consumption rate of antibiotics during the years 2018–2021 (Fig. 2) shows a clear collapse from March 2020, which is maintained with slight oscillations until September 2021, with the usual winter peak of antibiotic consumption in previous years being lost. In 2021, a rebound can be seen from October, although on a smaller scale than in 2018 and 2019.

In the other indicators analysed (Table 3), a downward trend was found in the percentage of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid consumption compared to the total (β=−0.43; p=0.046) and, conversely, a relative increase in the consumption of amoxicillin without clavulanic acid (β=0.61; p=0.047) and third-generation cephalosporins (β=0.38; p=0.001). By far the most prescribed third-generation cephalosporin, at 11,426 packs, was cefixime.

DiscussionMonitoring changes in antibiotic use indicators provides important information for identifying areas for improvement in prescribing, implementing the necessary interventions in the different healthcare system areas and guiding awareness campaigns aimed at the general population.

According to the national data provided by the PRAN for the total population in the community setting, the consumption rate of antibiotics for systemic use has gradually decreased in Spain in recent years.10 In 2020, there was a notable decrease in DID to 18.2 from 23.3 in 2019 (−21.9%).

In Asturias, considering only the population aged 14 or over, the decrease in 2020 was of a similar magnitude, from 16.6 to 12.2 DID (−23.6%).11 Our study shows that in the paediatric population, the decrease in antibiotic consumption was even more radical, with a drop of 54.3% from 2019 to 2020, and annual figures showing that this continued in 2021.

The decrease was more pronounced from March 2020, coinciding with the measures adopted by the Spanish Government during the state of alarm decreed on 14 March for the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. These measures included the closure of educational establishments, businesses and non-essential activities, lockdowns and restricted mobility, and the mandatory use of a mask for people aged six and over. In Asturias, educational centres had no face-to-face activity from 13 March to 22 September 2020.

As in our study, the curve published by the PRAN10 shows that the greatest year-on-year decreases in the rate of antibiotic consumption occur in the months of April and May 2020, coinciding with the first wave of the pandemic, and from October to November, where the characteristic winter peak did not happen. There are several factors that may have influenced this huge decline. One would be the difficulties in accessing PC as first contact had to be by telephone. The figures provided by the Health Observatory in Asturias, which do not distinguish between face-to-face and telephone consultations, show that from March 2020 to February 2021 total paediatric PC consultations decreased by only 10.9%, with an increase from August to December 2020 compared to the previous year.12 Published data from one health area in Asturias show that telephone consultations were predominant during this period.13 However, a notable reduction was also found in visits to paediatric hospital Accident and Emergency departments, where there were no restrictions to accessing face-to-face care.14 Therefore, rather than an actual limitation in accessibility to healthcare, the above would suggest there was less demand from families. This decrease in demand could partly be due to a reduction in the incidence of infectious diseases as a result of the measures applied against COVID-19. It is also possible that the pandemic has brought about a change in the way the population perceives infections. People may now be accepting of the fact that they are predominantly caused by viruses and of the ineffectiveness of antibiotics in the vast majority of paediatric infections. There may also be a greater awareness of the rational use of healthcare resources. Balaguer Martínez et al.15 associated frequent PC attendance with a higher rate of antibiotic prescribing in all paediatric age groups. It may also be the case that the availability of telephone appointments and for patient follow-up and the implementation of the electronic prescription have often made it easier for paediatric PC practitioners to defer the prescription of antibiotics. The way antibiotic use evolves in the coming years will show us whether or not any element of these changes is maintained over time.

It was difficult to access national data on the consumption of antibiotics for systemic use in the community in relation to the paediatric population to compare our results, as the PRAN publishes aggregate data for all ages. We believe that further studies are required, in addition to the development of indicators, which are both feasible and enable us to obtain homogeneous data for all the autonomous regions here in Spain.

Recently, using a methodology very similar to ours, Calle-Miguel et al.16 analysed changes in antibiotic use in the out-of-hospital setting in Asturias in the period 2005–2018. The DIDs they obtained were slightly higher than ours in the coinciding years (2014–2018), probably because their study included antibiotic prescriptions issued both in the PC setting and in hospital outpatient settings (for example, Accident and Emergency and outpatient clinics). Our study only included prescriptions issued in PC paediatric clinics and continuing care.

In other studies carried out in countries outside and within our setting,17–23 the same trend can be seen towards reduction in the rate of antibiotic consumption during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study by Magalhães Silva et al.,17 carried out in Portugal in the PC setting, shows a notable decrease in the prescribing of antibiotics, particularly in the months of April and May and from October to November 2020, with decreases of around 50% compared to the average monthly prescribing in 2018/2019. In the Canadian study by Knight et al.19 carried out at a community level, a 26.5% reduction was found in the rate of antibiotic use from March to October 2020 compared to the same period the previous year, with a 72% reduction in children and adolescents up to 18 years of age. In the United States, Chua et al.21 found that antibiotic dispensing to children decreased by 55.6% from April to December 2020 compared to April to December 2019.

Despite the decrease in the rate of antibiotic consumption and in the prevalence of use in the paediatric population, we found some variability in the results by therapeutic subgroups, although the differences were not generally very significant. A statistically significant decrease in the consumption of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was found compared to antibiotics for systemic use overall, coinciding with the aim to improve the indicator. Use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid continues to be lower than that of amoxicillin without a beta-lactamase inhibitor, maintaining the trend shown in another study carried out in the region of Asturias in the period 2005–2018.16

The relative decrease in the use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid could to a certain extent be due to a shift in its prescribing following the reintroduction on the market in 2015 of cefadroxil oral suspension, a first-generation cephalosporin particularly used in soft tissue infections and as an alternative in pharyngotonsillitis, the marketing of which had been suspended in 2013. This would also explain the progressive increase in cefadroxil use from 2015 on. Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid should only be used when the probable aetiological agent is a beta-lactamase producer, as a high percentage of PC infections are caused by microorganisms which do not produce beta-lactamases (such as pneumococcus or S. pyogenes). In addition, its use is associated with an increased risk of C. difficile infection and acute liver toxicity.24 Interestingly, unlike in the adult population here in Asturias,11 in the paediatric population, use of amoxicillin/clavulanic acid was notably lower than that of amoxicillin.

Another significant variation was the relative increase in the consumption of third-generation cephalosporins, particularly cefixime, both before and after the pandemic, including an increase in absolute terms between 2015 and 2018. Given its broad spectrum of action, cefixime should be reserved for highly justified uses in the outpatient setting, such as the empirical treatment of paediatric pyelonephritis.25 No increase in the use of cefixime was found in the adult population,11 and so it was probably due to the fact that there were shortages of the oral suspension format in Spain26 in 2014 and 2015, which would also explain the prescribing of other third-generation cephalosporins, such as ceftibuten or ceftriaxone during that same period.

A significant decrease was found in the proportion of macrolide use compared to antibiotics overall, with no such findings in the previously cited Asturian studies on the paediatric population16 or adult population.11 Macrolides are not first-line antibiotics in PC and should be reserved for specific cases (allergies to beta-lactams, respiratory infections due to atypical germs or B. pertussis infection).27 The trend of macrolide use does not seem to have been altered by the inclusion of azithromycin as a possible option for the treatment of COVID-19 in the early weeks of the pandemic.28

This study has some limitations, such as not including figures for prescriptions issued through health insurance companies or private practices. However, in 2021 Asturias recorded the second fewest visits per inhabitant to private specialist doctors of all the autonomous regions in Spain.29 We also did not include hospital consumption, which, apart from being much lower than community consumption,16 was also likely to decrease considering the drop in paediatric Accident and Emergency visits for infectious conditions in 2020.14 Another limitation is that we did not gather information on the indication for each prescription to better analyse changes in the consumption of certain antibiotics. The study design did not enable us to establish which factors most influenced the changes we detected. In Asturias, Programmes for the Optimisation of the Use of Antibiotics (PROA) have been in place in all health areas since 2018, but no actions specifically aimed at paediatric PC had been implemented until 2021, making it very difficult to estimate any impact they might have had on the changes observed.

In conclusion, after a slight downward trend in antibiotic use in the paediatric population in PC from 2014 to 2019, there was a drastic reduction from 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, which doubled that recorded in the adult population. Monitoring of these indicators will help determine to what extent these are temporary changes or whether they are sustained in the medium and long term. Additional, more detailed studies are needed to assess which factors have had more weight to be able to design more effective strategies to reduce the use of antibiotics.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.