To understand the experiences in nursing care in the prevention and treatment of delirium in people hospitalized in intensive care units.

MethodologyHermeneutic phenomenological qualitative study. The selection of participants was by intentional sampling: seven nursing assistants and eight nurses. Theoretical saturation was achieved. The phenomenological interview was applied to collect data from a central question and the analysis was carried out following the approaches of Heidegger’s hermeneutical circle.

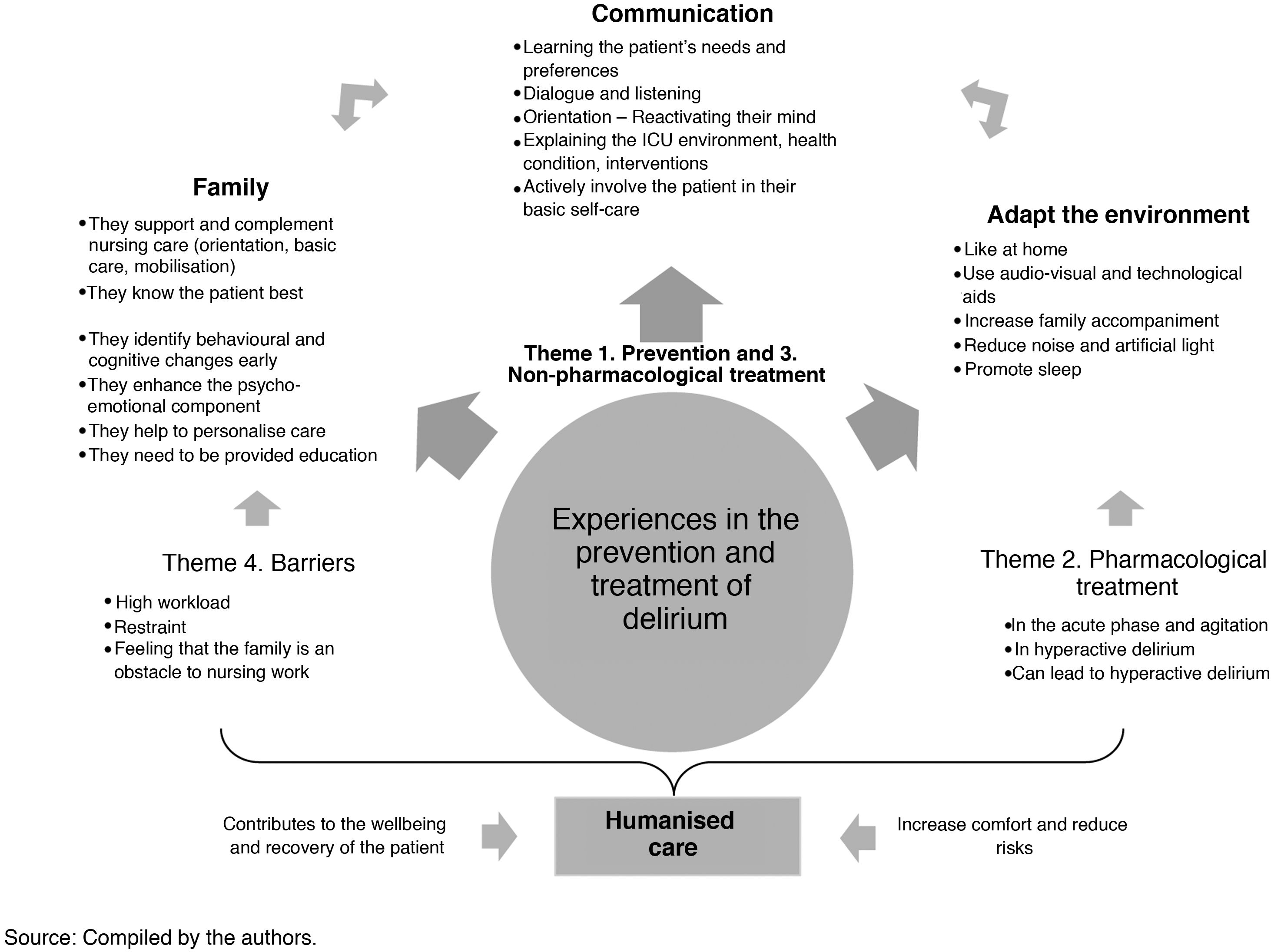

ResultsFour significant themes emerged from the analysis: (1) delirium prevention, (2) pharmacological treatment, (3) non-pharmacological treatment, and (4) barriers to non-pharmacological treatment. These themes were accompanied by 35 interrelated units of meaning: in the first theme, the most repetitive units were communication, orientation, and family bonding; in the second was the use of pharmacological treatment only in the acute phase; in the third was the modification of the environment according to the patient’s preference (where the family is a priority and strategies that provide cognitive and social stimulation can be reinforced), and in the fourth was the work overload for the nursing team.

ConclusionsThe experiences of the nursing team in the prevention and treatment of delirium in critically ill patients highlight that communication allows an approach to the patient as a human being immersed in a reality, with a personal history, needs and preferences. Therefore, family members must be involved in these scenarios, as they can complement and support nursing care.

Comprender las vivencias del cuidado de enfermería frente a la prevención y el tratamiento del delirium en personas hospitalizadas en unidades de cuidados intensivos.

MetodologíaEstudio cualitativo fenomenológico hermenéutico. La selección de participantes fue por muestreo intencionado: siete auxiliares de enfermería y ocho enfermeras. Se logró la saturación teórica. Se aplicó la entrevista fenomenológica para la recolección de datos a partir de una pregunta central y el análisis se realizó siguiendo los planteamientos del círculo hermenéutico de Heidegger.

ResultadosDel análisis, emergieron cuatro temas significativos: (1) prevención del delirium, (2) tratamiento farmacológico, (3) tratamiento no farmacológico y (4) barreras para el tratamiento no farmacológico. Estos temas estuvieron acompañados de 35 unidades de significado vinculadas entre sí: en el primer tema, las unidades más reiterativas fueron comunicación, orientación y vinculación de la familia; en el segundo tema fue el uso de tratamiento farmacológico sólo en fase aguda; en el tercer tema fue la modificación del ambiente según preferencia del paciente (donde la familia es prioritaria y permite reforzar estrategias que brinden una estimulación cognitiva y social), y en el cuarto tema fue la sobrecarga laboral para el equipo de enfermería.

ConclusionesLas experiencias del equipo de enfermería en la prevención y tratamiento del delirium en pacientes críticos destacan que la comunicación permite un acercamiento al paciente como ser humano inmerso en una realidad, con una historia personal, con necesidades y preferencias. Por lo tanto, en estos escenarios debe vincularse su familia, ya que puede complementar y apoyar del cuidado de enfermería.

- •

Knowledge about delirium has been enhanced through various studies, and its incidence, prevalence and associated factors are evident. Some interventions have also been tried; however, incidence of the condition remains high, and these interventions need to adapt to the realities of staff and institutions.

- •

This study contributes to the advancement of nursing knowledge on delirium because it reflects the knowledge emerging from nurses’ practical experience, analyses its convergence, and contrasts it with the available literature, finding that communication, family bonding, and adapting the ICU environment are effective in preventing and treating delirium, and form part of humanised care in the ICU.

- •

This study has a high impact for clinical practice, as it structures the knowledge on the prevention and treatment of delirium from the practical experiences of the nursing team, who are permanently with the critically ill patient and have complete leadership of non-pharmacological care.

- •

The participation of the nursing assistants lacked depth, as some responses were not very reflective and were similar in content, although they still responded to the question and the study objective. It was also rather difficult to recruit respondents as they did not have enough time and even said that they were tired or physical exhausted.

Delirium is an acute onset confusional syndrome with a fluctuating and indeterminate course, which presents in hyperactive, hypoactive, and mixed subtypes.1 This phenomenon is mainly of concern in intensive care units (ICUs), where its incidence remains high. For example, a 2017 study found a 50% incidence of delirium in a multicentre study with a sample of 520 critically ill patients,2 another 2018 study found a 19% incidence with a sample of 206 ICU patients,3 and in 2019, another study reported a 31.4% incidence of delirium in a sample of 280 patients admitted to ICUs.4 Likewise, other studies present a 44.4% prevalence of delirium in a group of 99 older adult critical patients,5 74% in 136 critical patients,6 and 80% in 230 ICU patients.7

The consequences of delirium greatly impact the quality of life of those who suffer from it, their families, ICU care professionals, and the health system in general, to the extent that it is currently considered a public health problem.8 Its main consequences include loss of factual memory (with a prevalence of delirium memories),9 increased hospital stay (especially in ICUs),2,7,10,11 increased hospital workload for the care team,11 increased days of mechanical ventilation,10,12 increased morbidity and mortality,2,7,13–15 early extubation failure,11 reduced cognitive and functional recovery,11 accelerated transition to dementia in the elderly, and reduced post-hospital physical functioning.16

These consequences require timely prevention and treatment measures17 to eliminate or minimise the highly negative impact of delirium. Nurses play a leading role in this scenario, as it has been shown that the aetiology of delirium is based not only on predisposing factors but also on precipitating factors, most of which are modifiable and associated with the care provided in the ICU, its environment, and pharmacological treatment.18,19 Thus, reducing the precipitating factors of delirium in the ICU effectively contributes to the provision of quality care centred on humanisation,20–22 an aspect promoted in the Humanisation of ICUs (HU-ICU) project, which proposes strategies that favour wellbeing,22,23 and which are part of the non-pharmacological measures for the prevention of delirium in the ICU.17

The assessment and intervention of nurses is therefore essential in the prevention and treatment of delirium, as they are leaders in clinical decision-making, have greater communication with patients and the medical team, and promptly assess the conditions of patients and their clinical outcomes.16,24–26 Thus, the aim of this study is to understand the experiences in the care provided by the nursing team in preventing and treating delirium in people hospitalised in ICUs.

MethodologyType of studyThis research used a hermeneutic phenomenological methodology, with Martin Heidegger as the main philosophical reference, to explore the consciousness and experiences of the respondents.27 This made it possible to study the phenomenon of delirium as it is lived, experienced, and perceived by the ICU nursing team. Thus, we interpreted everyday events and explained the nursing team’s lived experience,28,29 generating new knowledge based on meanings.

Selection of respondentsThe respondents were nursing assistants and nurses working in an ICU. This population was selected because it is common in some ICUs in the south of Colombia for nursing assistants to be more involved (with a ratio of one assistant to 2 patients and only one nurse to 7 to 10 patients), which means that nursing assistants provide basic care (cleaning, hygiene, wellbeing, feeding, and recording of vital signs) and they spend more time with the patients. Whereas nurses, in addition to providing complex care (assessment, administering medication, performing cures, invasive procedures, transferring, and moving patients), must also perform some administrative functions such as managing procedures and organising the department.

SamplingSampling was purposive; therefore, nurses and assistants were included if they met the following inclusion criteria: at least 6 months of experience in adult intensive care, currently working in the adult ICU of the institution where the study was conducted, and freely and voluntarily agreeing to participate in the study. Potential respondents who only performed administrative activities were excluded.

To collect the information, the objectives of this project were initially presented to the target population within the framework of institutional training. Then, with those who decided to participate voluntarily, a date, place and time were agreed for the interviews. In the collection of information, theoretical saturation of the data and the convergence of the different units of meaning was achieved with a sample of 8 nurses and 7 assistants.

Data collection and central questionThe nursing team selected participated in a phenomenological interview, the recommended collection instrument for this design,30–32 which lasted from 45 to 60 min. The interview began with a central question that guided how it developed: “What have your experiences been in providing care for the prevention and treatment of delirium in ICU patients?” The interviews were conducted individually, outside working hours, in a private and quiet place within the institution (meeting room), always safeguarding the confidentiality of the answers and the independence of the investigators from the health institution. During the conversation, sufficient time was used to delve deeper into aspects that the respondents considered relevant. It should be noted that the study investigators have extensive work experience in ICU, which helped in conducting the phenomenological interview and in the administrative processes to complete the research study.

Data analysisThe interviews were transcribed in Microsoft Word® following a transcription protocol adapted from Bejarano et al.,33 taking care to maintain the fidelity and accuracy of the interviews, so as not to omit any of the respondents’ comments within their context (Table 1). Similarly, comments corresponding to the investigator’s field notes were added to the transcript.

Protocol for transcribing the interviews.

| Conventions | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| (Laughter) | Laughter |

| (Rnd:) | Laughter during the conversation. After the 2-points intervention affected by laughter |

| (Coughing) | Coughing |

| (aha, uhum, hum, mm) | Sounds of assent: like aha, uhum, hum, mm, etc. |

| (---) | Silences |

| ¡ | Exclamatory utterances |

| ? | Interrogative utterances |

| / | Minimal pause |

| // | Pause |

| (///) | Interruption in recording |

| … | Pause at the end of an unfinished utterance or with suspended intonation |

| = | Self-interruption or abandonment of utterance (the speaker does not continue with the previous idea) |

| Emphasis | Fragment with clearly emphatic utterance |

| (→) | Lengthening of sound (without spaces) |

| (C/ut wo/rd) | Cut word |

| (∼) | Hesitation; brief hesitation |

| (Unintelligible) | Unintelligible fragment |

| # | Non-prosodic pause without expressive intention (e.g., when the speaker is thinking about a word or what they are going to say) |

| Xxx | Unintelligible fragments |

| (italics) | Clarifications or input from the interviewer |

Source: Adapted from Bejarano et al.33.

Data analysis was performed manually and permanently from the first interview using Excel® tables and Heidegger’s hermeneutic circle, which comprises, in order, pre-understanding (approaching the phenomenon by reading the discourses and literature), understanding (identifying units of meaning and convergence between them), and conducting both a new reading of the discourses and the literature, and a new analysis (identifying the units of meaning and the convergence between them), as well as re-reading the discourses and creating meaningful themes), and interpretation (making sense of the units ontologically and organising the themes to structure the phenomenon).34,35

To ensure the reliability of the analysis, the investigators independently calculated the concordance index of the units of meaning using Holsti’s reliability coefficient,36,37 which resulted in a score of 75%. This calculation made it possible to assess the level of communication and interaction between investigator and respondent, to define and delimit the units of meaning, and evaluate the central question and the approximation questions. Similarly, the criteria of rigour proposed by Lincoln and Guba38 were followed in terms of credibility in the faithful processing of the data, auditability with the complete recording of methodological decisions and results, transferability with the analysis of similarities between the findings of the study and the theory, and the relationship with the interpretation of the findings from the interests of the respondents and the community in general.

Ethical aspectsWe considered the Declaration of Helsinki and the International Ethical Guidelines for Health-related Research Involving Humans of the WHO, PAHO, and CIOMS. Colombian provisions were also considered, such as Resolution 8430 of 1993, which determines that this study represents minimal risk, Law 1581 of 2012, and Decree 1377 of 2013, guaranteeing that only the investigators would process the data, it would be collected exclusively for the relevant purposes, and it would be disclosed in a scientific manner safeguarding the identity of the respondents and the institution.

For the recording process of the interviews, conducted using a voice recorder, the investigators signed the confidentiality agreement, and the respondents signed consent forms for the study. The interviews were then transcribed and reviewed to remove any information that would identify the respondents, labelled with a number to ensure anonymity, and were finally deleted from the voice recorder and computer equipment once the research work was completed. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the institution where the research was conducted, by means of act number 001-001 of 28 January 2019.

ResultsOverall, 53% of the study respondents were nurses who provided direct care in the ICU at the time of the study, while the remaining 47% were nursing assistants. In terms of demographics, the nurse respondents ranged in age from 25 to 58 years, 62.5% were male, and had ICU experience ranging from 3 to 28 years. Meanwhile, the assistants ranged in age from 23 to 43 years, 87.5% were female, and had ICU experience of between 2 and 15 years (Table 2).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

| Characteristics | Nurses n = 8 (53%) | Nursing assistants n = 7 (47%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female n (%) | 3 (37.5) | 6 (85.7) |

| Male n (%) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (14.3) |

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 34 (±13.87) | 32 (±11.82) |

| Length of experience | ||

| Years, mean (SD) | 10.33 (±7.63) | 9 (±4.53) |

SD: standard deviation, n: number of respondents.

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Analysis of the interviews helped towards an understanding as to how the ICU nursing team approaches care to prevent and manage delirium. Thus, 35 units of meaning were grouped under the following themes: (1) Prevention of delirium, (2) Pharmacological treatment of delirium, (3) Non-pharmacological treatment of delirium, and (4) Barriers to non-pharmacological treatment of delirium (Table 3).

Significant themes, units of meaning and verbatims emerging from the data.

| Themes and units of meaning | Verbatim N° |

|---|---|

| Significant theme 1: measures and strategies for preventing delirium | |

| Support with family members to prevent delirium | 008, 009, 010, 025, 026, 040, 041, 063, 137, 158 |

| Use of non-pharmacological measures to prevent delirium | 019 |

| Progressive reduction of sedatives | 059 |

| Communication with the patient | 020, 023, 144, 047, 057, 060, 113, 114, 117, 119, 121, 122, 124, 125, 136, 138, 139, 141, 144, 145, 146, 160, 174 |

| Reduce pain | 061 |

| Promote wellbeing measures | 024, 062, 112 |

| Change how we behave | 056, 151 |

| “I think that we’re an important part of that moment” In Vivo code | 120 |

| Establish a more affectionate relationship not a nurse-patient relationship, but as a friend | 085 |

| Identify in the journal all the patient’s physical, psychological, and family needs | 067 |

| “Goal-based sedation management is a challenge, an obligation and a duty” In vivo code | 058 |

| Educational intervention for the patient and their family before admission to ICU | 002, 005, 006 |

| “They have the most contact with the patients” In vivo code (nursing) | 074 |

| “Treat them with sort of more love, I don’t know more affection” In vivo code | 106 |

| Significant theme 2: pharmacological treatment | |

| Calming and relaxing effect | 037, 045, 043, 126, 167 |

| First option in the treatment of delirium in the acute phase | 007 |

| According to level of agitation | 030, 036, 107 |

| Conscious sedation | 078, 098, 104, 116 |

| Not adequate because it leads to a different type of delirium | 016 |

| Significant theme 3: non-pharmacological treatment measures | |

| Family bonding in non-pharmacological treatment | 003, 004, 011, 029, 032, 038, 039, 042, 049, 079, 082, 102, 110, 111, 130, 155, 156, 164, 171, 175 |

| Reorientate, activate their mind | 035, 054, 093, 118, 131, 135, 143, 149, 170 |

| Use of audio-visual and technological aids | 012, 080, 101, 109, 159, 161, 162, 163, 172 |

| Extend length of family accompaniment time | 017, 048, 089, 092, 099, 100, 157, 166 |

| Communication with the patient | 028, 051, 081, 108, 129, 132, 173, 176 |

| Need for nurse-patient interaction | 076, 087, 088, 134 |

| Interdisciplinary work | 066, 069, 072, 097, 115, 128, 147, 154, 015 |

| Change the environment to make them feel at home | 013, 014, 018, 050, 094, 142 |

| Ensure there is more staff | 090 |

| Reduce noise, light, and promote sleep | 055, 168, 169 |

| Be patient with and understand them | 034, 148, 152 |

| Mobilise early | 070, 133, 165 |

| Involve the patient in their basic self-care | 068, 071 |

| Significant theme 4: barriers to non-pharmacological treatment | |

| A high workload restricts non-pharmacological treatment | 065, 083, 084, 105 |

| Made uncomfortable due to the permanent presence of the family | 044, 103 |

| Technology can distance the patient | 075 |

| Lack of knowledge or not using scales to diagnose delirium | 064, 140 |

| Restraint as a control measure | 001, 027, 046, 052, 077, 091, 095, 096, 127, 150, 153 |

| “Families do now recognise our work” In Vivo code | 043 |

Source: Compiled by the authors.

The unit of meaning mentioned most frequently was communication between the nurse (or nursing assistant) and the patient. This strategy makes it possible to meet the basic need of human beings to interact through speaking and listening, to obtain basic information that helps guide care and create greater trust between these two actors. Several respondents agreed that introducing the team at the beginning of the shift is of great value, as it helps patients to get to know the unfamiliar people who will oversee their care during their stay in the unit: “Em, it’s important to talk to the patient, to keep them informed about the time, the date, that it’s daytime, and it’s very important to do this at every change of shift… To always keep the patient oriented. Not introducing yourself… nursing staff being present and that they will be accompanying the patient during the shift, and all of that, I think this is important to prevent it” (NURSE 3, #047)

Likewise, they express that physiological conditions such as hearing, which continue to be active despite sedation during mechanical ventilation, should not go unnoticed: “And bearing in mind that we are caring for socially active people who need to communicate, and that in some cases despite the fact that they are ventilated, they are actually listening to us” (NURSE 4, #057).

In addition to the above, it is possible to interpret from the respondents’ accounts that, despite their health condition, patients have concerns about the outside world, as they are human beings with feelings and emotions. In this regard, the nursing team needs to maintain a closer and more conversational relationship with the patient, which goes beyond procedural care that is limited to routine tasks, and which focuses on care that includes concern for the whole person (not only their physical but also their emotional state).

Similarly, family support was highly valued by the respondents, as visits from their loved ones provided spaces for interaction where they could share different situations, such as giving affection, talking about routine life, or news from home, talking about events in the region and the world, among others. According to the nurses, this scenario helps patients to remain immersed in their social role and, above all, feel surrounded with affection: “So, the family, what I was saying is that they are closer to them, supporting them, telling them about the normal things that have happened in the home… Showing them the reality of the news, which is, well, not so pleasant, but yes, the reality of the day, so that they are not so lost from the outside world” (NURSE 8, #025)

Likewise, some respondents referred to examples of successful strategies for the prevention of delirium in other institutions based on flexible visiting hours and increasing family accompaniment, which increases the well-being of the patient and benefits them in their multiple human dimensions, indirectly helping them to recover their health: “[The strategy of] open-door ICU […], yes, so longer visiting hours have been arranged so that the patient can spend more time with their family, especially the patient who is fully oriented, to avoid delirium and the patient with delirium or who is coming out of prolonged sedation so that this change can be mitigated” (NURSE 2, #041)

In addition to the above, educating the patient and family about events and risks that can occur during the ICU stay is highly valued as a preventive measure. The respondents stated that it is of great importance to allow the use of items such as books, tablets, or other means of distraction to keep patients adequately cognitively stimulated: “So that they don’t feel that it is so cold, so grey, that they don’t, no, they don’t have to do anything, so they lose ideas…” (NURSE 8, #019).

It is also noteworthy that among the interventions to prevent delirium, one nurse mentioned the importance of using goal-directed sedation, describing it as follows (imbued with a noteworthy sense of obligation): “The management of goal-directed sedation is a challenge, an obligation, and a duty” (NURSE 4, #058).

To conclude this theme, the respondents acknowledged the contribution of emotional care to the wellbeing of patients in the ICU, described as a factor that positively influences early discharge from the unit. In this regard, the role of nurses is considered really important for the recovery of the patient’s health as they exercise an altruistic role: “So, we try to be like psychologists with them and talk to them and tell them, look, we have to try to be calm so that you get out of here faster, so I think we are an important part at that moment” (ASSISTANT 1, #120)

When exploring the pharmacological management of delirium, the respondents identified that administering drugs with a calming and relaxing effect was usually the first option for the treatment of delirium during the acute phase: “Medication, well, that helps, well, like, the acute part, in the moment of agitation when the patient gets out of control” (NURSE 1, #007). Other respondents highlighted medication as a second option after non-pharmacological treatment: “It is no longer just, mmm, you could say non-pharmacological treatment, but you have to start using drugs” (NURSE 2, #036). For other respondents, however, the patient’s level or degree of agitation indicated to the treating doctor the need or otherwise to use drugs: “Yes, sometimes they [doctors] say that when patients are very agitated, they say that they should be started on dexmedetomidine to calm them down” (ASSISTANT 1, #116).

Some of the respondents acknowledged that conscious sedation could help prevent delirium and stated that they preferred its use over benzodiazepines: “The doctor is also told to please prescribe drugs that try to prevent delirium, for example, conscious sedation medication such as dexmedetomidine, which, well, helps a little bit to control the patient’s perception during the stay in the unit” (NURSE 5, #098)

It is also important to highlight that the respondents reported their experience of an imminent risk when opting to use drugs, because they do not cure delirium but rather favour the transition between the hyperactive and hypoactive subtypes: “That’s another thing that can really present itself when you use drugs to try to control the hyperactive effect, it ends up leading to a hypoactive one then there you start a, it’s… it’s… it’s… mixed, it becomes a mixed delirium…” (NURSE 1, #016)

This theme comprises 13 units of meaning, within which family bonding in non-pharmacological treatment was the most constant, expressed in 19 fragments by 10 respondents. This unit is associated with other units called “extension of visiting time” and “psychological and emotional recovery of patients”. It should be noted, as presented below, that the nurses recognise the great contribution of the family, which may facilitate the move to an open-door ICU focused on humanised care: “They are told to come, accompany them, but also tell them things about the home… Eh… how he feels… eh, the dog, the cat, the birds… everything that they, that, that, that the patient generally finds in their daily routine, well because they start again sort of, re-establish their life […]. The family does play a very, very important role in patient recovery, that is, feeling loved, loved, accompanied, that… that kind of reassures them a lot, a lot, a lot” (NURSE 5, #115)

The next unit under this theme was reorientation, a measure that reactivates the patients’ cognition by orienting them in time, place, condition, and reality: “One always tries to intervene and tell the patients […] what the situation is like, where they are and that nothing of what they are seeing is real” (NURSE 3, #054). Likewise, the use of audio-visual and technological aids (television, radio or that preferred by the patient) is considered a strategy that helps the patient remain in a social and cultural reality: “Providing the patient with other types of distraction, not just reading, something like that, but many patients like to watch the news, those things, so we should add this type of audio-visual aid to an ICU” (NURSE 7, #080).

Other units of meaning emerging under this third theme were patient communication and interdisciplinary work. Communication extends from prevention and now as a treatment measure to encourage interaction and maintenance of personal reality. On the other hand, with interdisciplinary work, the need was highlighted for the entire care team to help treat delirium through their specific functions: “Everyone must help to treat delirium, so in relation to the doctor, they guide the treatment accompanied by the other professionals we support, taking into account sedation, analgesia, we also work hand in hand in therapies, specifically physical and respiratory therapies” (NURSE 4, #069)

The respondents also stressed that nurses can adapt the environment to make the patient feel at home. This helps towards a deep understanding of the patient as a human being with a history, with preferences, with needs and with a family, who deserves personalised care to help reduce delirium. This is achieved through adequate communication, anticipation, and interpretation of the patient’s non-verbal expressions: “It would be very good, for example, to play a game of chess or a crossword puzzle with the patient, something for the patient to say well, I am no longer here simply because of my heart failure, they come, they put me on medication and that’s it, they leave. No, we need to make them feel at home” (NURSE 7, #088)

Likewise, the respondents indicated that measures in the ICU environment should be adjusted, such as reducing noise and light to promote the patient’s sleep and thus reduce delirium, an aspect for which there is also evidence as a preventive and therapeutic intervention for delirium. Similarly, the unit of meaning “be patient and understand them” shows that the nursing team is empathetic with the patients, in such a way that they understand the cognitive disturbance that causes aggressive behaviour: “Try to be patient with them all the time, because that’s a matter of patience, eh, you can’t start to argue with them or fight them” (ASSISTANT 5, #148).

The last 2 units of meaning were “mobilise early” and “involve the patient in basic self-care”. These units allowed patients to be protagonists and participate in their recovery, because they are no longer conceived as passive subjects receiving care, but are understood as active human beings who are part of the process to speed up their recovery and reduce events such as delirium: “Muscle stimulation is very good, they should move from the bed to a chair as soon as possible, yes? That as soon as they have, physically, they have extra dynamic mobility they can be taken to the bathroom, that’s very good […]. Patients should be able to wash in the shower, see to their physiological needs in a bathroom and not be scared there in bed, good” (NURSE 4, #071)

This theme comprised 6 units of meaning, of which the most frequent was “restraint as a control measure applied by the nursing assistants”, as they are afraid that delirium may lead to the patient suffering an adverse event that puts their safety at risk: “Especially restraining them, because by immobilising them carrying out restraint measures, they prevent things from being removed, for example, patients who are intubated, who have catheters” (NURSE 5, #096). In addition to the above, the use of restraint was also described as necessary to guarantee the workers’ own safety, which is why a feeling of fear for their own safety is evident: “It was necessary to restrain him, he became aggressive with all the staff and also [with] the family, so it was like a risk to my life with this patient, being so big and so strong” (NURSE 7, #091). In this regard, one of the respondents also acknowledged that immobilisation has a negative effect on patients: “We often have to restrain them, so that sometimes causes more, more anxiety for them” (ASSISTANT 5, #150).

The high workload was also recognised as a barrier to non-pharmacological treatment, as it restricts it. In this sense, it was perceived that the nursing team is aware of the great importance of direct care of critically ill patients, yet, in many cases, they must give priority to administrative activities: “It’s true that we sometimes have very limited time, we have a high, a high workload, because it’s not only the care but also the administrative workload, then sometimes direct contact and direct care is limited […], then we put it aside” (ENF 4, #065)

Another barrier to implementing non-pharmacological measures was not knowing about or using scales that diagnose delirium: “There are people who are unaware that these types of scales exist, and those who are aware of them do not dedicate time to them” (NURSE 4, #064). One respondent even indicated that technology could take the nursing team away from the patient, specifically referring to central monitoring, which results in assistants not keeping an eye on the patient. This experience raises concerns, as it reduces the possibility of communication with the patient and early detection of signs of delirium, while increasing the risk of adverse events.

We describe above that of the non-pharmacological interventions the importance of the family was highly valued. However, two respondents reported feeling uncomfortable with the constant presence of the patient’s loved ones: “With family members it is different because we have to do procedures, give medication, so it is a bit uncomfortable, but we try to do everything the best we can” (NURSE 5, #103). One nurse even stated that “the family does not recognise our work” (NURSE 2, #043), which is why it is necessary to educate both family members and the nursing team so that they become facilitators and participants in care.

Convergence of themes and units of meaningThe experiences of the ICU nursing team centred on the themes identified; however we found several convergences on an interpretative re-reading of these and of the units of meaning that emerged (Fig. 1); 4 essential elements stand out within these that are linked and described in the following statement: communication is an essential element in the development of the care of the ICU patient, as it allows us to approach them as a human being immersed in a reality which is not only determined by a pathological situation, but is also mediated by their personal history, needs and preferences. This communication process requires a permanent dialogue between the various actors involved in care, in which the family plays a special leading role by complementing and supporting nursing care. Therefore, families must be educated beforehand so that their actions can enhance and favour care.

In addition to communication and family support, the ICU environment itself is a highly valued element involved in preventing delirium and in care, thus directly affecting the patient’s wellbeing throughout their hospital stay. In this sense, this environment needs to be adjusted so that it becomes an adjuvant to recovery.

There are also noteworthy barriers that limit the implementation of non-pharmacological treatment, such as the high workload due to the number of patients and the functions assigned to the nursing team. These barriers hinder the possibilities of providing the patient quality care and affection, as evidenced by the limited interaction time, an aspect that can directly or indirectly influence the patient’s progress. However, this problem of high workload, a consequence of the local health system, cannot become an excuse for health professionals, and in particular nursing teams, not to develop actions and strategies for comprehensive and humanised care.

DiscussionWhen analysing the results of the present study with respect to the literature, similarities and complementarities were found in most cases. Initially, the units of communication and family bonding were constant in both the first and third themes of this research. In this regard, Martínez et al.,39 through a multicomponent intervention that included the family, achieved 24%–38% reduction in the incidence of delirium. Similarly, Barnes-Daly et al.,40 in their study, state that communication with the family is adequate if simple, specific language is used and if sufficient time is devoted.

Other authors mention various strategies with the family, such as involving them in medical rounds,41–44 or holding conferences where they are given adequate information about the equipment, diagnosis, and treatment.40,41,43,44 Likewise, Marra et al.45 add that the family should become an active partner or ally in decision-making and multi-professional care, Prescott and Costa46 state that loved ones can be involved in treatment plans, and Leblanc et al.47 mention that emotional and educational interventions can be delivered, as their presence creates a sense of familiarity and security for patients.48

Despite the above, the respondents in the present study expressed the need to educate the patients’ relatives, as they stated that they could even become “another patient” if they did not have adequate information about delirium, because this caused them stress and anguish when they saw the behavioural changes in their loved one. This coincides with the findings of Martínez et al.,39 who, through a qualitative phenomenological study, found that family members were unaware of delirium and considered its symptoms to be a natural consequence of a critical illness.

In turn, within the first theme of prevention strategies, the respondents stated other interventions such as extending visiting hours or enabling open-door ICUs. This is like Morandi et al.49 who suggest that visits should be for more than 5h per day when there is no open-door ICU. This study also found similarity in the recommendations related to the use of goal-guided sedation,40,41,44,45,50 with the central aim of keeping the patient in a calm and alert state.44 Additionally, the emotional care of the patient to avoid delirium was highlighted in the present research study, which is consistent with the influence of psychological antecedents associated with delirium such as dementia and depression.51

The second theme was pharmacological treatment, which the respondents described as necessary only in agitation or hyperactive delirium, although from their experiences they stated that this did not improve the patients’ condition, but also led to hypoactive delirium. In this respect, Zamoscik et al.8 found similar results, as in their research the participants indicated that the drugs available to treat delirium were ineffective and even exacerbated it. In contrast, Marra et al.45 suggest using pharmacological treatment only after correcting modifiable deliriogenic factors. However, this study suggested the use of conscious sedation with dexmedetomidine to prevent delirium instead of traditional sedation with benzodiazepines. This aspect has also been identified by other authors, who add that the former may reduce the incidence of delirium and days of mechanical ventilation.45,52

The third theme, non-pharmacological treatment, was the most developed by the respondents in this study. In addition to strategies aimed at family bonding and communication, other units of importance were found, such as reorientation, an aspect highlighted in other studies as very useful for treating delirium,50,53,54 or help with cognitive stimulation.54,55 In addition, Reznik and Slooter52 suggest employing various strategies such as providing a clock for each patient, orienting them in place and time, memory stimulation and the use of pre-recorded messages for patients to listen to family guidance if they cannot be present in the ICU. The need for interaction, dialogue and listening to the patient, learning about their reality, being patient and understanding them was also highlighted. In relation to this aspect, Marra et al.41 and Sweeney42 confirm that knowing the patient helps to understand them as a person and to make them more comfortable.

The third theme also recognised the importance of adapting the ICU environment to patients’ realities, tastes, and preferences. This is like that recommended in the guidelines for the management of agitation, pain and delirium56 and in several research studies,41,42,44–46,49,52,57 that indicate that environmental interventions on noise and artificial light can be made to improve sleep hygiene. Along the same lines, there are other interventions related to comfort especially when bathing, changing position,47 and resting by providing devices such as hearing aids and glasses.44

Other units in this theme were like the findings of various studies, such as the interdisciplinary work described by Weber et al.58 as essential for the care of the critically ill patient and recommended in interventions such as the ABCDEF package, in which nurses, physicians, intensivists, and physical and occupational therapy professionals develop preventive and treatment measures for delirium.59 In this vein, the use of audio-visual and technological aids to provide wellbeing was covered in the study by Munro et al.53 and is recommended as a measure that favours humanised care in the ICU.23 Similarly, early mobilisation is widely recommended by multiple studies, which insist that it should be initiated as early as possible.42,44,46,57

However, in the fourth and final theme on barriers to the development of non-pharmacological treatment, it was found that, although physical restraint was necessary to ensure patient safety, it could also increase patient anxiety. This was like the findings of Freeman et al.60 who found that the use of restraint helped to keep patients safe. Likewise, the findings of Pan et al.61 corroborate that these practices progressively generate a risk for delirium in patients depending on how often they are used.

In addition, the high workload was considered a barrier to non-pharmacological treatment, like that reported by Zamoscik et al.,8 who found that the numerous responsibilities in ICUs and the prioritisation of medical treatment generally prevent nurses from concentrating on patients’ psychological needs. The lack of knowledge of or not using scales that diagnose delirium was also identified as hindering its detection and timely intervention, an aspect confirmed by Truman et al.43 and Mart et al.,44 who recommend that these instruments should be applied several times or at least more than twice a day.

Finally, the interviews showed that the family was considered an obstacle to nursing work. This is consistent with the findings of Mitchell et al.,14 who, after an intervention with the family to prevent delirium in the ICU, interviewed the nurses to assess their acceptability. They identified that nurses were sometimes afraid of families or felt uncomfortable, overwhelmed, or stressed.

ConclusionsIn this study, understanding nurses’ care experience involved developing communication strategies with the patient, the family, and the work team, to promote humanised care that could adapt the ICU environment to the patient’s preferences, needs, wellbeing and comfort. This allows interventions for the prevention and treatment of delirium, especially those that favour sleep, adaptation, and the active participation of the patient in their recovery.

Likewise, the family is a key actor in the patient’s care, as they know the patient best and therefore can promptly identify and report behavioural and cognitive changes. Family members can also help provide reassurance, security, comfort, companionship and guidance, measures that are effective in the prevention and treatment of delirium. Therefore, the family is an essential ally of nursing care, particularly when educated about delirium and the patient’s conditions.

Finally, it is striking that none of the respondents mentioned interventions focused on the spiritual wellbeing of critically ill patients, nor was there any mention of post-intensive care syndrome. Therefore, the nursing team should be educated about the variety of non-pharmacological interventions that include addressing patients’ spiritual needs, which can have a positive impact on preventing delirium and post-intensive care syndrome, which has short- and long-term consequences on the quality of life of patients and their families.

FundingThis paper has received no funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

The authors would like to thank the respondents in this study, nurses from an intensive care unit in Colombia, whose participation enabled the development of this research.