Bulevirtide (Hepcludex®) is the first drug approved for the treatment of chronic hepatitis D (CHD), unlike the current off-label treatment (PEG-IFN-α), limited in clinical practice and associated with post-treatment relapses. In a hypothetical cohort of CHD patients in Spain, the study aim was to compare the efficiency of bulevirtide with PEG-IFN-α in terms of clinical events avoided and associated cost savings.

MethodsA validated economic model reflecting the natural history of the disease was used to project lifetime liver complications and costs for two hypothetical cohorts treated with bulevirtide or PEG-IFN-α. The model considered progression to complications such as decompensated cirrhosis (DCC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation (LT), and death. The efficacy rates used at 24 and 48 weeks were defined as the combined response rate for bulevirtide and undetectable HDV RNA to PEG-IFN-α. The numbers of clinic events and associated costs were evaluated from the perspective of the National Healthcare System.

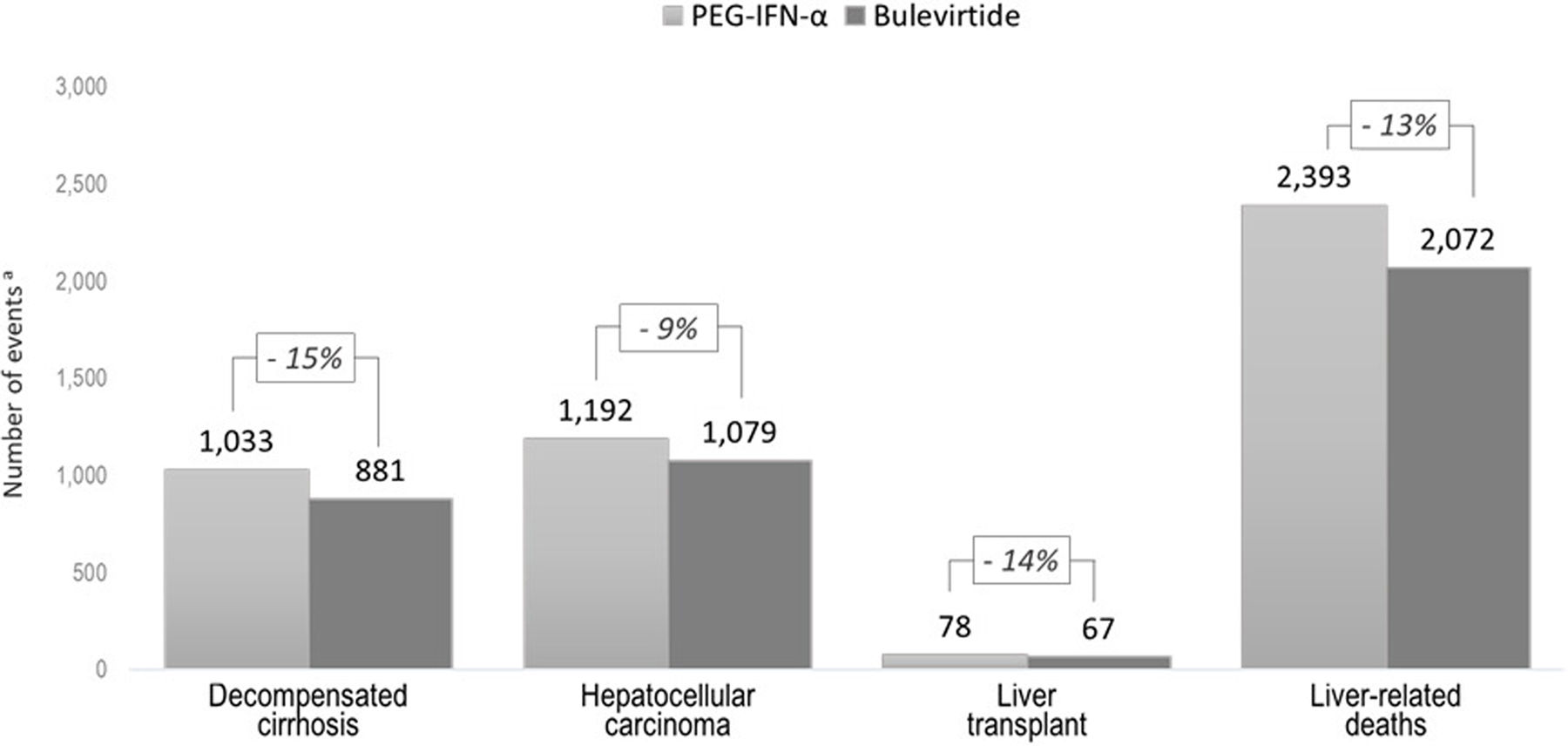

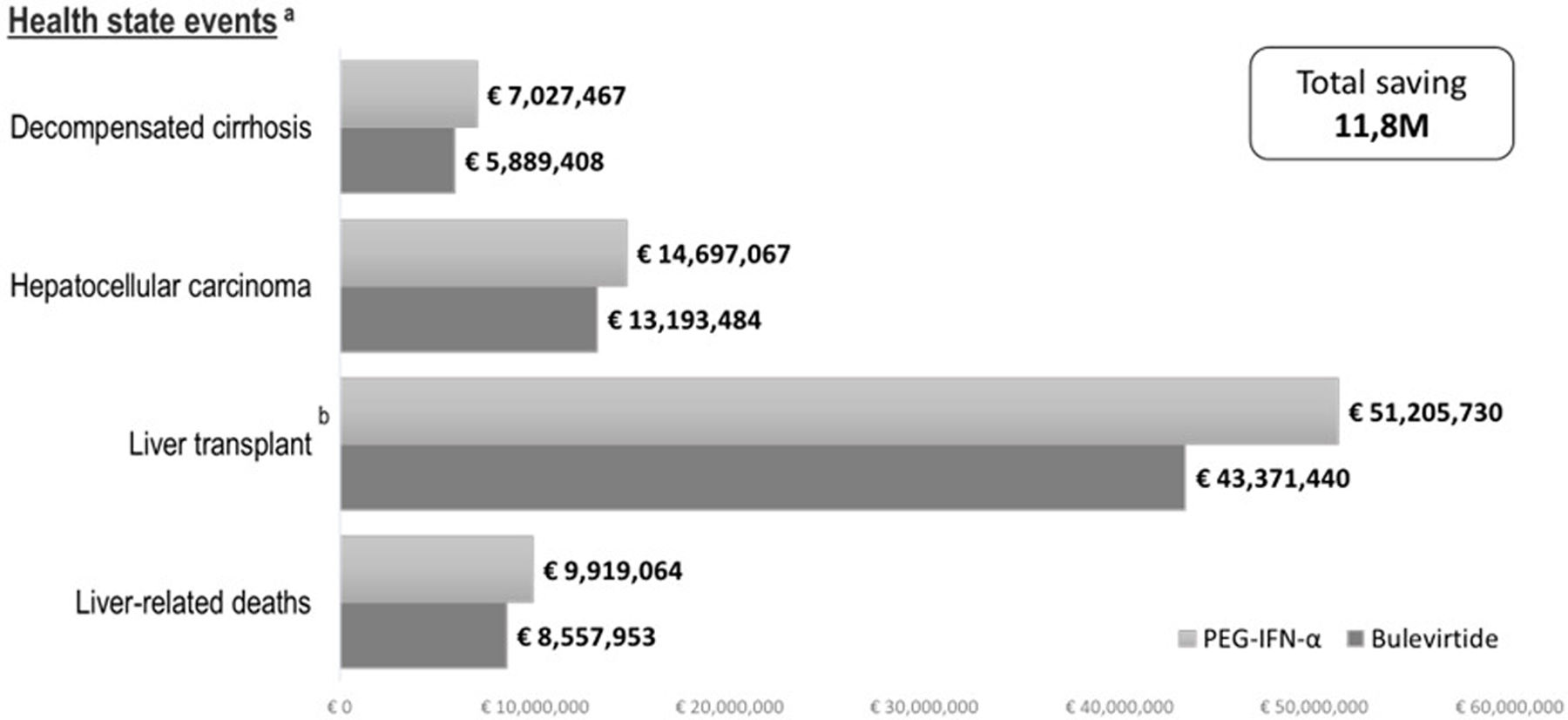

ResultsIn a hypothetical cohort of 3882 patients, bulevirtide reduced the numbers of complications events in comparison to PEG-IFN-α (152 DCC, 113 HCC, 11 LT, and 321 deaths over a lifetime). This was associated with a reduction of event-related costs of €11,837,044 (DCC €1,138,059; HCC €1,503,583; LT €7,834,291; and death €1,361,111).

ConclusionIn patients with CHD, bulevirtide could prevent a significant number of clinical events compared to PEG-IFN-α and contribute to cost savings through these reduction in liver complications. Further testing for hepatitis D virus is needed so that more patients can benefit from bulevirtide.

La bulevirtida (Hepcludex®) es el primer tratamiento aprobado para la hepatitis D crónica (HDC), a diferencia del tratamiento con PEG-IFN-α (fuera de indicación) limitado en la práctica clínica por estar asociado a recidivas tras el tratamiento. El objetivo fue comparar la eficacia de bulevirtida vs. PEG-IFN-α en términos de eventos clínicos evitados y ahorro de costes asociados en una cohorte hipotética de pacientes con HDC en España.

MétodosSe utilizó un modelo económico validado que refleja la historia natural de la enfermedad mediante la simulación de complicaciones hepáticas (cirrosis descompensada [CD], carcinoma hepatocelular [CHC], trasplante hepático [TH] y muerte) durante la vida del paciente. Se emplearon tasas de eficacia a las 24 y 48 semanas, considerando la tasa de respuesta combinada para bulevirtida y el ARN-VHD indetectable para PEG-IFN-α. Los eventos clínicos y sus costes asociados se evaluaron desde la perspectiva del Sistema Nacional de Salud.

ResultadosEn una cohorte hipotética de 3.882 pacientes, bulevirtida redujo el número de complicaciones en comparación con PEG-IFN-α (152 CD, 113 CHC, 11 TH y 321 muertes, a lo largo de la vida). Esto supuso una reducción de 11.837.044€ (1.138.059€ CD, 1.503.583€ CHC, 7.834.291€ TH y 1.361.111€ muertes hepáticas).

ConclusionesEn pacientes con CHD, bulevirtida (Hepcludex®) podría prevenir un número significativo de complicaciones clínicas en comparación con PEG-IFN-α y contribuir al ahorro de costes a través de esta reducción de las complicaciones hepáticas. Es necesario realizar más pruebas de detección del virus de la hepatitis D para que más pacientes puedan beneficiarse de bulevirtida.

Chronic hepatitis D (CHD) is the least common and considered most severe of viral hepatitis.1–3 It is caused by the hepatitis D virus (HDV).4,5 HDV is a RNA virus that requires the hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for infecting the hepatocytes.4,5 In addition, HBV/HDV infection may occur simultaneously named coinfection, or the individual may acquire HDV when already is chronically infected with HBV (superinfection).6 HBV/HDV coinfection usually is autolimited with HBsAg clearance, and less than 5% will develop chronic infection; while HBV/HDV superinfection usually progress to advanced fibrosis and cirrhosis in a short period.6

Compared to HBV monoinfection, HDV coinfection has been characterized by a rapidly progressive disease, and correlates with an increased risk of liver cirrhosis (10–15% in the first 2 years and 70–80% up to 10 years), which increases the likelihood of decompensated cirrhosis (DCC), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), liver transplantation (LT), and mortality.4,5

Worldwide, current estimates suggest that HDV has a prevalence ranging from 0.16% to 0.98% in the general population; and the prevalence of HDV among people HBsAg-positive ranges from 4.5% to 13.02%.7–9 According to data published in Spain, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis D in HBsAg carriers was estimated at 5–7.7%.10–12 In addition, patients with HDV confirmed by HDV-RNA account for about 73% of the antibody positive (anti-HDV) patients.13

Currently, there is no curative therapy for CHD. The standard of treatment is to minimize disease progression using peginterferon alfa (PEG-IFN-α) off-label, including best supportive care in cases of liver disease (fibrosing cirrhosis stages). In clinical practice, the use of PEG-IFN-α is limited to a small number of patients and the efficacy is low defined by persistent suppression of HDV RNA (10–30% after 48-week of therapy) in HDV-infected patients.14 Also, PEG-IFN-α is associated with relapses in HDV replication after treatment, as well as frequent and severe side effects that affect patients’ quality of life.15–17

The goal of treatment of chronic hepatitis delta is to prevent the development of complications of liver disease and liver disease-related death.18 Bulevirtide (Hepcludex®) is the first and only drug approved for the treatment of chronic HDV infection.19 Bulevirtide is a lipopeptide (myristoylated N-terminal and aminated C-terminal 47-amino acid) derived from HBV l-protein, that specifically binds to the HBV/HDV receptor entry (sodium taurocholate cotransporter polypeptide, NTCP), hence blocking HBV access into hepatocytes.19 The clinical efficacy of bulevirtide was investigated in an open-label, randomized, controlled Phase III clinical trial (MYR 301), as well as two open-label, randomized, controlled Phase II trials (MYR202 and MYR203).19–21 Treatment criteria efficacy was the combined virological response including HDV-RNA undetectability (log10IU/mL from baseline; and normalization of ALT values, measured at 24 and 48 weeks.20

In the national setting, data on the efficiency of bulevirtide compared to PEG-IFN-α was not available. In order to determine the potential longer-term economic benefit of bulevirtide from a Spanish perspective, the study aimed to compare the efficiency of bulevirtide versus PEG-IFN-α in terms of clinical events avoided and associated cost savings in a hypothetical cohort of patients with CHD in Spain.

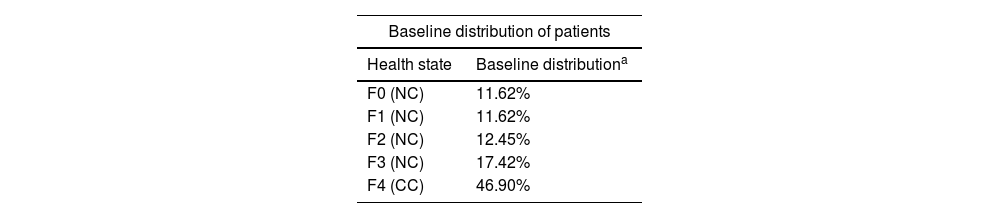

MethodsA previously validated model (decision tree followed by a Markov model developed in Microsoft Excel®) was adapted to simulate the progression of patients with CHD over their lifetime.22 The simulation considered two hypothetical identical cohorts of 3882 patients to compare two therapies, one treated with bulevirtide and the other with PEG-IFN-α. The cohort considered in the analysis refers to adult CHD patients with different degree of fibrosis and all compensated liver disease The decision tree assumed that a proportion of treated patients would achieve a response at 24 and 48 weeks, based on the combined efficacy response endpoint from the Phase III clinical trial (MYR301).20,22 The mutually exclusive health states correspond to worsening as the disease progressed: non-cirrhotic (NC) stages (F0–F3); compensated cirrhosis (CC) or stage 4 of fibrosis (F4); states with long-term liver complications (DCC, HCC, and LT); post liver transplantation (PLT) and finally death. The transition probabilities used to reflect disease progression between health states were derived from publications comparing disease progression in HDV/HBV co-infected individuals versus HBV mono-infected individuals (Table 1).22 This approach has been validated by clinical experts in pathology, due to the greater robustness of the HBV data and the well-established relationship between the faster progression of HDV/HBV compared to HBV mono-infected patients.22 As simulation results, the model estimated the number of clinical events and their respective costs associated to the health states (DCC, HCC, LT, and liver-related deaths) for the hypothetical cohort of 3882 patients treated with either bulevirtide or PEG-IFN-2α.

Parameters considered in the model.

| Baseline distribution of patients | |

|---|---|

| Health state | Baseline distributiona |

| F0 (NC) | 11.62% |

| F1 (NC) | 11.62% |

| F2 (NC) | 12.45% |

| F3 (NC) | 17.42% |

| F4 (CC) | 46.90% |

| Transition probabilities | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health state | Disease course | Responder patients | |

| From | To | Annual value | Annual value |

| Fx | Fx+1 (combined response endpoint) | 15.1%1,28,b | 3.94%44 |

| HCC | 1.4%29,30,c | 0.50%30 | |

| CC | DCC | 10.7%32,34,d | 2.50%44 |

| HCC | 6.2%30,32,e | 2.25%30 | |

| EM | 7.3%33,34,f | 0.98%44 | |

| DC | HCC | 7.8%30,32,g | 7.8%30,32,g |

| LT | 1.6%32 | 1.6%32 | |

| EM | 15.6%33 | 15.6%33 | |

| HCC | LT | 1.6%32 | 1.6%32 |

| EM | 56.0%32 | 56.0%32 | |

| LT | EM | 21.0%32 | 21.0%32 |

| PLT | EM | 5.7%32 | 5.7%32 |

| Unit cost | |

|---|---|

| Health state | Annual cost (€, 2024)37 |

| DCC | € 2034.82 |

| HCC | € 9110.78 |

| LT | € 179,007.17 |

| PLT | € 55,976.80 |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9101.61 |

CC: compensated cirrhosis; DCC: decompensated cirrhosis; EM: excess mortality; F0: fibrosis stage 0; F1: fibrosis stage 1; F2: fibrosis stage 2; F3: fibrosis stage 3; F4: compensated cirrhosis; Fx+1: fibrosis stage that achieve the combined response endpoint; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; LT: liver transplant; NC: non-cirrhotic; PLT: post-liver transplant.

Patient with CHD defined by detectable HDV RNA and compensated liver disease. The base case was obtained from the literature, with a mean age of 47 years, and a slightly higher proportion of men (59.0%), in accordance with the characteristics of the Spanish population.11,13 The initial distribution of patients by fibrosis stage was based on phase III clinical trial (MYR301) with an adjustment for stages F0–F3.20,23 Consequently, at baseline, patients were assigned to each treatment (bulevirtide or PEG-IFN-2α) with a proportion of fibrosis stages of 23%, 13%, 17%, and 46% for F0–F1, F2, F3, and F4, respectively (Table 1).

Patients were on treatment (bulevirtide or PEG-IFN-2α) in stages F0 to F4 until development of long-term complications (DCC, HCC, LT, PLT, and death). Transitions between health states depended on response or non-response to treatment (responders and non-responders). Responders to bulevirtide were defined as having met the combined response endpoint (defined as an undetectable HDV RNA or ≥2log10IU/mL decrease, and normal ALT) at 24 and 48 weeks of therapy (36.7% and 44.9%, at 24 and 48 weeks, respectively),20,24 while non-responders did not reach this criterion. Responders to PEG-IFN-2α were defined by undetectable HDV RNA at 24 and 48 weeks of therapy (30.0% and 34.0%, respectively).25 Disease progression in responder patients were more slowly than in non-responder, this progression was determined by hazard ratios (HR) of HDV-RNA undetectability and combined with the disease course transition probabilities.22 In addition, response to bulevirtide may induce regression of fibrosis (rate of 8.8% from F3 to F2)26 and cirrhosis (rate of 13.3% from F4 to F3).27 Patients continued treatment with bulevirtide as long as there was any clinical benefit, and PEG-IFN-α patients were treated up to 48 weeks.

The analysis considered treatment drop-out and discontinuation for different reasons as not achieved the combined response endpoint, achieved HBsAg seroclearance, and disease progression to long-term complications. The discontinuation rate (5.1% for bulevirtide and 33.3% for PEG-IFN-2α) was established by the hepatologist expert panel, as no discontinuations were reported in the bulevirtide clinical trials. These untreated patients progressed according to the natural course of the disease, based on publications comparing disease progression in HDV/HBV coinfected individuals versus treated HBV-only infected patients.1,28–34 The annual HBsAg seroclearance rate for both treatments, and spontaneous clearance in the untreated patient was similar (<1.13%).35 Also, overall mortality and mortality due to liver diseases were obtained from official Spanish data.36

To estimate the clinical events avoided and the economic outcome of treating patients with a chronic disease such as HDV, a lifetime horizon (60 years) was considered with a duration of each cycle of 24 weeks and a half-cycle correction.

The Spanish National Health System (NHS) perspective was applied, using an annual discount rate of 3.0% for outcomes of avoided clinical events and cost. A panel of expert hepatologists validated and approved the clinical input values according to clinical practice in the Spanish setting.

From the perspective of the analysis, direct healthcare costs, such as the cost of managing disease progression by health status of liver complications, were assessed. The annual health state costs for liver complications used are described in Table 1.37 These were applied to the proportion of responders and non-responders for each treatment. All costs were expressed in euros at January 2024 (€, 2024).

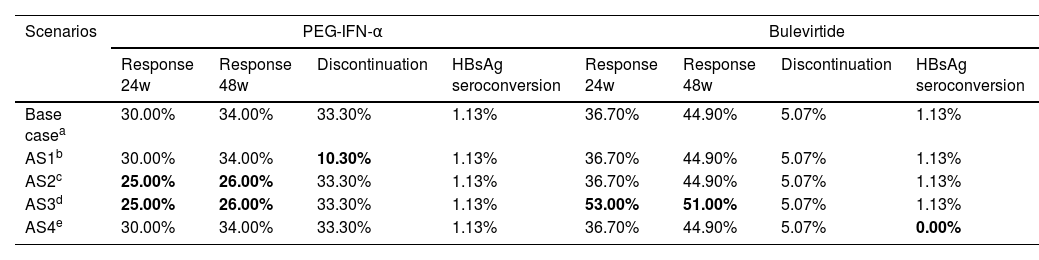

Alternatives scenariosAlternative scenario (AS) analyses were performed to assess the uncertainty associated with an annual discontinuation rate, efficacy data and HBsAg seroconversion (Table 2).

Summary of data used in the alternatives scenarios.

| Scenarios | PEG-IFN-α | Bulevirtide | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response 24w | Response 48w | Discontinuation | HBsAg seroconversion | Response 24w | Response 48w | Discontinuation | HBsAg seroconversion | |

| Base casea | 30.00% | 34.00% | 33.30% | 1.13% | 36.70% | 44.90% | 5.07% | 1.13% |

| AS1b | 30.00% | 34.00% | 10.30% | 1.13% | 36.70% | 44.90% | 5.07% | 1.13% |

| AS2c | 25.00% | 26.00% | 33.30% | 1.13% | 36.70% | 44.90% | 5.07% | 1.13% |

| AS3d | 25.00% | 26.00% | 33.30% | 1.13% | 53.00% | 51.00% | 5.07% | 1.13% |

| AS4e | 30.00% | 34.00% | 33.30% | 1.13% | 36.70% | 44.90% | 5.07% | 0.00% |

The first alternative analysis (AS1) considered an annual discontinuation rate of 10.3% for patients treated with PEG-IFN-α22 (instead of 33.3% for the base case).25 As the base case assumed an undetectable HDV RNA response as the combined response for PEG-IFN-α, the second (AS2) and third (AS3) scenarios considered a variation of the PEG-IFN-α or bulevirtide efficacy data. In the AS2, PEG-IFN-α efficacy corresponded to ALT normalization, which was 25% at 24 weeks and 26% at 48 weeks25 with no change in the bulevirtide efficacy. In AS3, the efficacy corresponded to ALT normalization in both therapies, bulevirtide efficacy corresponding to ALT normalization responses of 53% at 24 weeks and 51% at 48 weeks24 and PEG-IFN-α efficacy corresponded to ALT normalization, which was 25% at 24 weeks and 26% at 48 weeks.25 In the fourth analysis (AS4), to consider a scenario reflecting a higher HBsAg negative rate with PEG-IFN-α treatment, a 0% HBsAg seroconversion rate was considered for bulevirtide.

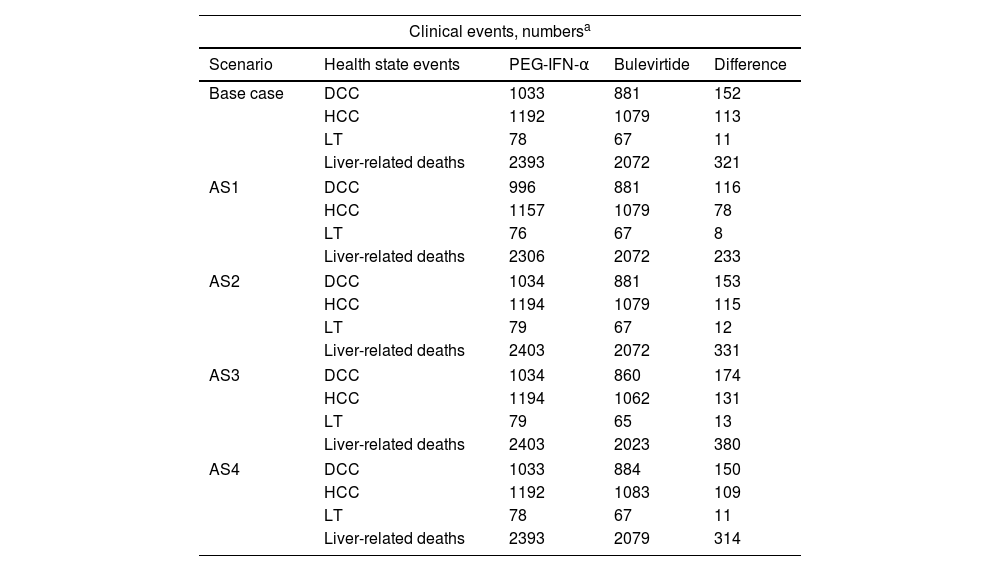

ResultsThe results of the base-case scenario analysis indicated that treatment with bulevirtide (Hepcludex®) would reduce liver complications events than PEG-IFN-α. In a hypothetical cohort of 3882 patients, treatment with bulevirtide reduced the numbers of clinical events (152 DCC and 113 HCC events) with a greater impact on the reduction of number of liver transplantation cases (11 LT) and decrease of number of liver-related deaths (321 deaths) in comparison to PEG-IFN-α (Fig. 1). In terms of cost, these results showed a reduction in costs related to DCC, HCC, LT, and death related to liver complications of €1,138,059, €1,503,583, €7,834,291, and €1,361,111, respectively. This would result in a total reduction of event-related costs of €11,837,044 (Fig. 2).

Comparison of clinical events between bulevirtide and PEG-IFN-α over patient's lifetime. (a) The discount rate was applied to calculate the number of events associated with each health condition. The hypothetical cohort established was 3882 patients for each treatment. A cost-effectiveness analysis model over a lifetime horizon was used to determine the outcomes for each cohort.

Comparison of cost of clinical events between bulevirtide and PEG-IFN-α. (a) The discount rate was applied to calculate the cost associated with each health condition. (b) The costs of liver transplantation include the costs of liver transplantation and post-liver transplantation.

In the AS1, by varying the annual discontinuation rate of 10.3% for patients treated with PEG-IFN-α, the estimated number of events over the time horizon decreased to 116 DCC, 78 HCC and 8 LT related to liver complications, and 233 liver-related deaths in favor of bulevirtida, representing a total cost reduction of €8,702,165.

The AS2 showed that bulevirtide reduced 153 DCC, 115 HCC, 12 LT, and 331 deaths from liver complications versus PEG-IFN-α, resulting in a total cost saving of €12,331,898. The AS3 results estimated a case number difference of 174 DCC, 131 HCC, 13 LT, and 380 liver-related deaths in favor of bulevirtide, leading to a total cost saving of €14,225,775 versus PEG-IFN-α.

In AS4, when the HBsAg seroclearance rate was varied to 0% in patients treated with bulevirtide, the estimated number of events over the period was reduced to 150 DCCs, 109 HCCs and 11 LTs related to liver complications and 314 liver-related deaths in favor of bulevirtide, for a total cost reduction of €11,597,742.

All numbers of liver complications events and their respective cost were showed in Table 3.

Alternatives scenarios results (hypothetical cohort of 3882 patients).

| Clinical events, numbersa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Health state events | PEG-IFN-α | Bulevirtide | Difference |

| Base case | DCC | 1033 | 881 | 152 |

| HCC | 1192 | 1079 | 113 | |

| LT | 78 | 67 | 11 | |

| Liver-related deaths | 2393 | 2072 | 321 | |

| AS1 | DCC | 996 | 881 | 116 |

| HCC | 1157 | 1079 | 78 | |

| LT | 76 | 67 | 8 | |

| Liver-related deaths | 2306 | 2072 | 233 | |

| AS2 | DCC | 1034 | 881 | 153 |

| HCC | 1194 | 1079 | 115 | |

| LT | 79 | 67 | 12 | |

| Liver-related deaths | 2403 | 2072 | 331 | |

| AS3 | DCC | 1034 | 860 | 174 |

| HCC | 1194 | 1062 | 131 | |

| LT | 79 | 65 | 13 | |

| Liver-related deaths | 2403 | 2023 | 380 | |

| AS4 | DCC | 1033 | 884 | 150 |

| HCC | 1192 | 1083 | 109 | |

| LT | 78 | 67 | 11 | |

| Liver-related deaths | 2393 | 2079 | 314 | |

| Clinical events, cost associateda | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scenario | Health state events | PEG-IFN-α | Bulevirtide | Difference |

| Base case | DCC | € 7,027,467 | € 5,889,408 | € 1,138,059 |

| HCC | € 14,697,067 | € 13,193,484 | € 1,503,583 | |

| LT | € 51,205,730 | € 43,371,439 | € 7,834,291 | |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9,919,064 | € 8,557,953 | € 1,361,111 | |

| AS1 | DCC | € 6,760,878 | € 5,889,408 | € 871,470 |

| HCC | € 14,247,794 | € 13,193,484 | € 1,054,311 | |

| LT | € 49,152,336 | € 43,371,439 | € 5,780,896 | |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9,553,442 | € 8,557,953 | € 995,489 | |

| AS2 | DCC | € 7,069,527 | € 5,889,408 | € 1,180,119 |

| HCC | € 14,765,962 | € 13,193,484 | € 1,572,478 | |

| LT | € 51,532,210 | € 43,371,439 | € 8,160,770 | |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9,976,483 | € 8,557,953 | € 1,418,530 | |

| AS3 | DCC | € 7,069,527 | € 5,710,509 | € 1,359,018 |

| HCC | € 14,765,962 | € 12,949,431 | € 1,816,531 | |

| LT | € 51,532,210 | € 42,118,585 | € 9,413,625 | |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9,976,483 | € 8,339,883 | € 1,636,601 | |

| AS4 | DCC | € 7,027,467 | € 5,908,393 | € 1,119,074 |

| HCC | € 14,697,067 | € 13,242,632 | € 1,454,434 | |

| LT | € 51,205,730 | € 43,513,221 | € 7,692,509 | |

| Liver-related deaths | € 9,919,064 | € 8,587,340 | € 1,331,724 | |

AS: alternative scenario; DCC: decompensated cirrhosis; HCC: hepatocellular carcinoma; LT: liver transplant.

The results of the analysis showed that bulevirtide was more efficient than PEG-IFN-α, as measured by the number of events avoided and the costs associated with those events. The base case results and AS remark the benefit of using bulevirtide (Hepcludex®) treatment versus PEG-IFN-α, showing a reduction in liver complications (base case reduction range of 9–15%). This benefit was also reflected in the costs of the health states generating a total saving of €11.8 million. It was difficult to find comparisons with other studies because, to our knowledge, this is the first study of the number of events avoided and their associated costs, by therapies evaluated in the Spanish setting.

Nowadays, emerging clinical and economic evidence supports bulevirtide use. The clinical evidence results from national studies and economic evidence showed that introduction of bulevirtide could modify the healthcare resource consumption and costs in patients with HDV compared to HBV.

The literature suggests that patients with hepatitis delta progress more rapidly than monoinfected patients, develop more liver complications, require more medical care, and represent a greater cost burden than HBV alone.35,38 This highlights the need for improved detection and treatment of all stages of fibrosis, including cirrhosis, in accordance with clinical guidelines.39 The model used established a relationship between the efficacy of the treatments assessed through the combined response endpoint considering the slowing of disease progression which, in turn, leads to changes in disease management.22 So, the decrease in disease complication events was correlated to slower disease progression due to bulevirtide treatment. This is an important finding based on the fact that hepatitis D impacts significantly on liver morbidity and mortality.40

Limitations of the analysis include firstly that the model includes efficacy at 48 weeks, although longer-term results (144 weeks) have been available. In this sense, we wanted to be conservative, as the model has been previously validated with results at 48 weeks.22 A second limitation was the efficacy data of the therapies used, although the efficacy data came from different trials, the scenarios analyzed with other efficacy hypotheses showed that bulevirtide always had benefits in terms of avoided events and costs. Another limitation is that the bulevirtide data is based on clinical data that lacks external validity in real-world settings and that the hypothetical cohort of CHD patients may not necessarily reflect the characteristics of CHD patients in Spain and may affect the results; to better address this issue, future research should be conducted with real-world data.

Given that disease events occur over the long term, there is currently an emphasis on the need for the measurement of short-term clinical outcomes to be linked to long-term clinical outcomes.41 In this regard, bulevirtide has been shown to be safe and effective in real-world settings, including in patients with advanced compensated cirrhosis.41 Emerging therapies for the treatment of HBV infection may involve the elimination of HDV due to its dependence on HBV.42 And therefore, during the course of the disease, we need to leverage the possibilities of opportunistic intervention, identifying patients in a prompt manner, and as a consequence reducing the number of patients with complications. This also has a positive impact on reducing the cost to the healthcare system.43

ConclusionTreatment with bulevirtide for CHD could avoid a significant number of clinical complications and liver mortality compared to PEG-IFN-α, leading to a slower disease progression and cost savings originated by the reduction in the number of liver-related events.

Based on these data and the benefit of bulevirtide, we believe that the clinical and economic benefit of treatment would be greater if population screening were also carried out with the involvement of national and regional health authorities in Spain.

FinancingThis work has been funded by Gilead Sciences Spain.

AuthorshipMB, JLC, MAR, HC, RDH and MAC contributed to the conception and design of the study. RDH, NEC and HC contributed to data collection from the scientific literature. MB, JLC and MAR validated the model inputs and provided information on the management of hepatitis D patients in Spain. RDH, NEC and MAC carried out the adaptation of the analytical model. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, writing of the manuscript, critical revision of the intellectual content and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of interestMaría Buti received consultancy and speaking fees from Gilead Sciences, Janssen Cilag and Abbvie.

José Luis Calleja has received consultancy and advisory fees from Gilead Sciences, Abbvie and MSD.

Miguel Ángel Rodríguez has carried out remunerated activities for Abbvie, Astellas, Advanz, Astellas, Amgen, Astra Zeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Ever Pharma, Galapagos, Gilead, GSK, Intercept, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lundbeck, Manapharma, MerckSerono, MSD, Novartis, Roche, Sandoz, Serono, Tesaro, UCB, Vertex and ViiV.

Helena Cantero is an employee of Gilead Sciences Spain.

Raquel Domínguez-Hernadez, Nataly Espinoza-Cámac, and Miguel Ángel Casado are employees of PORIB and received fees from Gilead Sciences for their consultancy services in relation to the development of this work.

Artificial intelligence (AI)No artificial intelligence assisted technology was used in the preparation of this manuscript.