Acute pancreatitis is a frequent inflammatory gastrointestinal disorder with high mortality rates in severe forms. An early evaluation of its severity is key to identify high-risk patients. This study assessed the influence of waist circumference together with hypertriglyceridemia on the severity of acute pancreatitis.

MethodsA retrospective study was performed, which included patients admitted with acute pancreatitis from March 2014 to March 2021. Patients were classified into four phenotype groups according to their waist circumference and triglyceride levels: normal waist circumference and normal triglycerides; normal waist circumference and elevated triglycerides; enlarged waist circumference and normal triglycerides; and enlarged waist circumference and triglycerides, namely hypertriglyceridemic waist (HTGW) phenotype. Clinical outcomes were compared among the groups.

Results407 patients were included. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and intensive care unit admission were most frequent among patients in the HTGW phenotype group, at 44.9% and 8.2%, respectively. The incidence of local complications was higher in the normal waist circumference with elevated triglycerides group (27%). On multivariable analysis, an enlarged waist circumference was related to an increase of 4% and 2% in the likelihood of developing organ failure and SIRS, respectively. Hypertriglyceridemia was an independent risk factor for both organ failure and local complications.

ConclusionsHTGW phenotype was significant related to developing of SIRS. It seems that an enlarged waist circumference has a greater role than hypertriglyceridemia in the development of SIRS. Obesity and hypertriglyceridemia were both independent risk factors for organ failure. Patients with hypertriglyceridemia were more likely to develop local complications.

La pancreatitis aguda es una patología frecuente con altas tasas de mortalidad en sus formas graves. Este estudio evaluó la influencia de la circunferencia de la cintura (CC) junto con la hipertrigliceridemia en la gravedad de la pancreatitis aguda.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo que incluyó pacientes con pancreatitis aguda desde 2014 hasta 2021. Los pacientes se clasificaron en cuatro grupos fenotípicos según su CC y los niveles de triglicéridos: CC normal y triglicéridos normales, CC normal y triglicéridos elevados, CC aumentada y triglicéridos normales, y CC aumentada y triglicéridos elevados, es decir, el fenotipo cintura hipertrigliceridémica (HTGW).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 407 pacientes. El síndrome de respuesta inflamatoria sistémica (SIRS) y la admisión a la unidad de cuidados intensivos fueron más frecuentes entre los pacientes con fenotipo HTGW, en 44,9 y 8,2%, respectivamente. La incidencia de complicaciones locales fue mayor en el grupo de CC normal con triglicéridos elevados (27%). En el análisis multivariable, una CC aumentada se relacionó con un aumento de 4 y 2% en la probabilidad de desarrollar fallo orgánico y SIRS, respectivamente. La hipertrigliceridemia fue un factor de riesgo tanto para el fallo orgánico como para las complicaciones locales.

ConclusionesEl fenotipo HTGW se relacionó con el desarrollo de SIRS. Parece que una CC aumentada tiene un papel más importante que la hipertrigliceridemia en el desarrollo de SIRS. La obesidad y la hipertrigliceridemia fueron factores de riesgo independientes para el fallo orgánico. Los pacientes con hipertrigliceridemia tenían más probabilidades de desarrollar complicaciones locales.

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is one of the most frequent inflammatory gastrointestinal disorders worldwide. The global pooled incidence is reported to be 34 cases per 100,000 people per year, with North America and the Western Pacific having the highest rates.1,2 Most of the patients admitted have a mild disease and a short hospital stay.3 Nevertheless, in severe cases, the mortality rate rises to 30–50%, mainly due to its association with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and multiple organ failure.4,5 As a result, an accurate and timely assessment of the AP severity is critical for identifying high-risk patients, which improves outcomes and lowers the mortality rate.

Obesity (defined as a body mass index [BMI]>30kg/m2) is a probed independent risk factor for AP, which is associated with a complicated course, especially abdominal obesity (characterized by a large waist circumference [WC]). This can be explained by the fact that visceral adipose tissue leads to a hypersecretion of proinflammatory mediators such as interleukin 6 and tumor necrosis factor, increasing the inflammatory response when pancreatitis is present.6,7 In addition, hypertriglyceridemia (HTG), which is one of the most frequent lipometabolic disorders, is an independently significant risk factor for the development of organ failure in AP.8–11

The concept of hypertriglyceridemic waist (HTGW) phenotype was formulated by Lemieux et al. in 2000, which includes HTG and a large WC.12 This phenotype has been used to identify the characteristics of excessive visceral adipose tissue. Furthermore, these comorbidities have been associated with metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and hypertension. In recent years, interest in the relationship between HTGW and AP has increased.4,5 This study was aimed to assess the influence of HTG and an enlarged WC on the severity of AP.

Materials and methodsStudy designWe performed a retrospective study from a prospective database of patients diagnosed with AP who were admitted from March 2014 to March 2021 at the Gastroenterology Service of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid, Spain.

The exclusion criteria included age <18 years, recurrent pancreatitis, previous diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis, history of surgery involving the pancreas, history of cancer, pregnancy, and incomplete data in the electronic medical record.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid under the number PI-22-2850.

Data collectionData were obtained from electronic medical records at Hospital Universitario de Valladolid. Information collected included patient clinical demographic data, etiology, severity, length of stay, local complications, organ failure, systemic complications, SIRS, intensive care unit (ICU) admission, interventional procedure need, and mortality.

Study definitions and classificationsAccording to the revision of the Atlanta classification, the diagnosis of AP required at least two of the following features: abdominal pain consistent with AP, biochemical evidence of pancreatitis (amylase or lipase at least three times greater than the upper limit of normal), and/or characteristic findings on contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or transabdominal ultrasonography.13

The severity of pancreatitis was classified as mild (absence of organ failure and the absence of local or systemic complications), moderately severe (presence of transient organ failure and/or local or systemic complications within 48h), and severe (presence of persistent organ failure involving one or more organs and lasting >48h).4,13

Organ failure is defined as a score ≥2 points for one of three organs (respiratory, cardiovascular or renal system) of the modified Marshall scoring.14 Systemic complication was defined as an exacerbation of a pre-existing co-morbidity such as heart failure, coronary artery disease, chronic lung disease, or chronic kidney disease precipitated by AP.13

SIRS was defined as the presence of two or more of the following criteria: temperature >38 or <36°C, heart rate >90beats/min, respiratory rate >20breaths/minute or partial pressure of CO2 <32mmHg, leukocyte count >12,000 or <4000/microliters or >10% immature forms.13,15

Large WC was defined as ≥102.0 for males and ≥88.0cm for females.16 This measurement was made by using a measuring tape at the midpoint between the lowest rib margin and iliac crest after a normal exhale.

HTG was defined as serum triglycerides (TG) ≥1.70mmol/L.16,17 As the measurement of TG levels is not routinely performed in the emergency department, this measurement was carried out 24h after the admission to hospital. The waist triglyceride index (WTI) was calculated by using the formula: WTI=WC (cm)×TG (mmol/L).18

Heavy alcohol drinking was defined as a consumption of >4 standard drinks/day in men or >3 standard drinks/day in women, or >14 standard drinks/week in men and >7 standard drinks/week in females.19

Definition of phenotypesAccording to WC and TG, participants were divided into four phenotype groups: NWNT (normal WC+normal TG); NWET (normal WC+elevated TG); EWNT (enlarged WC+normal TG); HTGW (enlarged WC+elevated TG).4,5,17,20

Statistical analysisIn the case of a normal distribution, continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation (SD) while they were expressed as the median and interquartile range in a nonnormal distribution. Categorical variables as frequencies and proportions. For continuous variables, phenotype groups were compared by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post hoc correction or Kruskal–Wallis test according to the result normality test. For categorical data, we use the Chi-square or 2-tailed Fisher's exact test. Univariable and multivariable logistic regressions were used to calculate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) for predictors of organ failure, SIRS and local complications. The following variables were included: age, hypertension, diabetes, heavy alcohol consumption, smoking, BMI, high levels of TG, WC and WTI. Predictors that were determined to be significant by univariable analysis remained in the adjusted model. Statistical analyses were calculated using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 21.0.

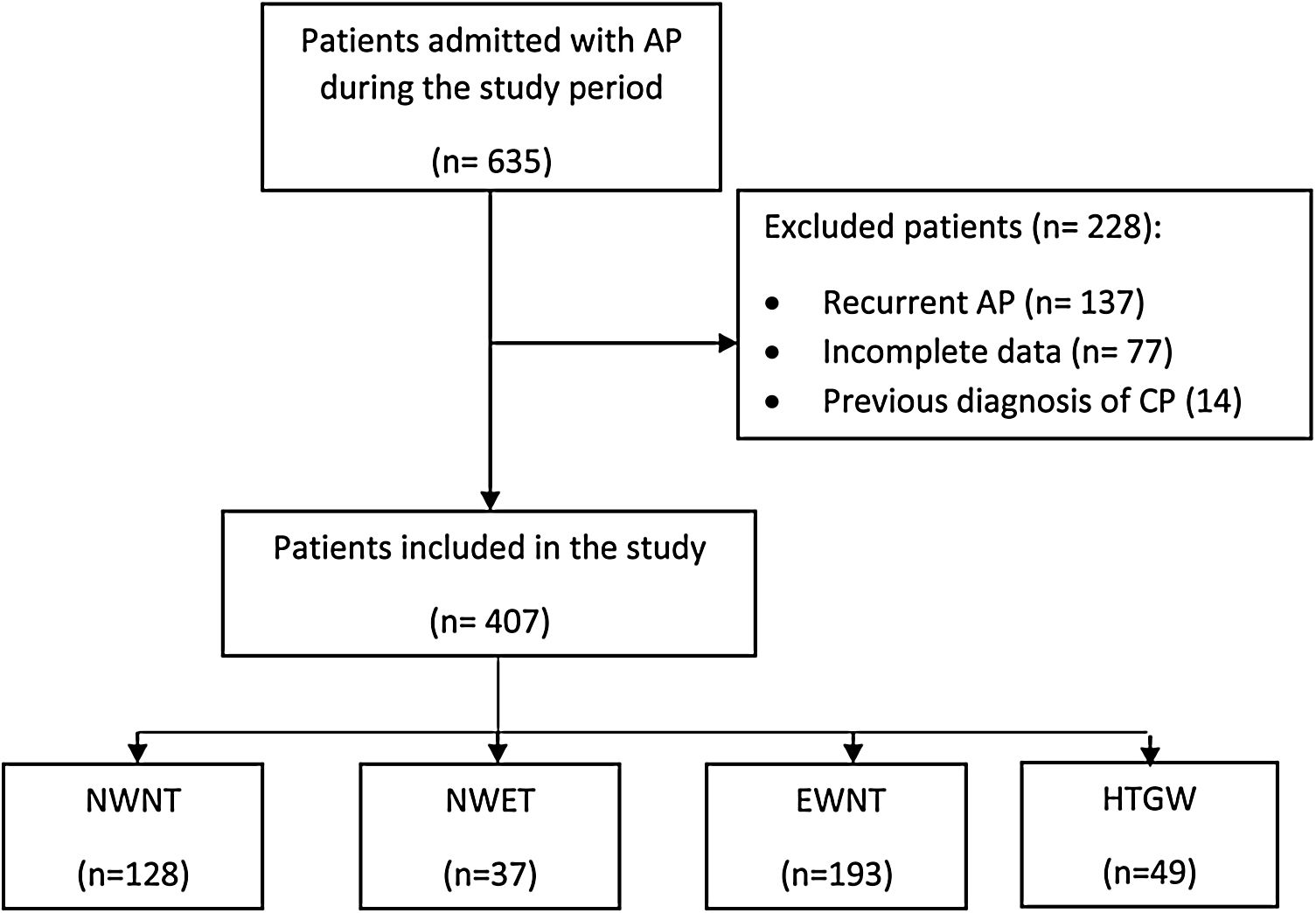

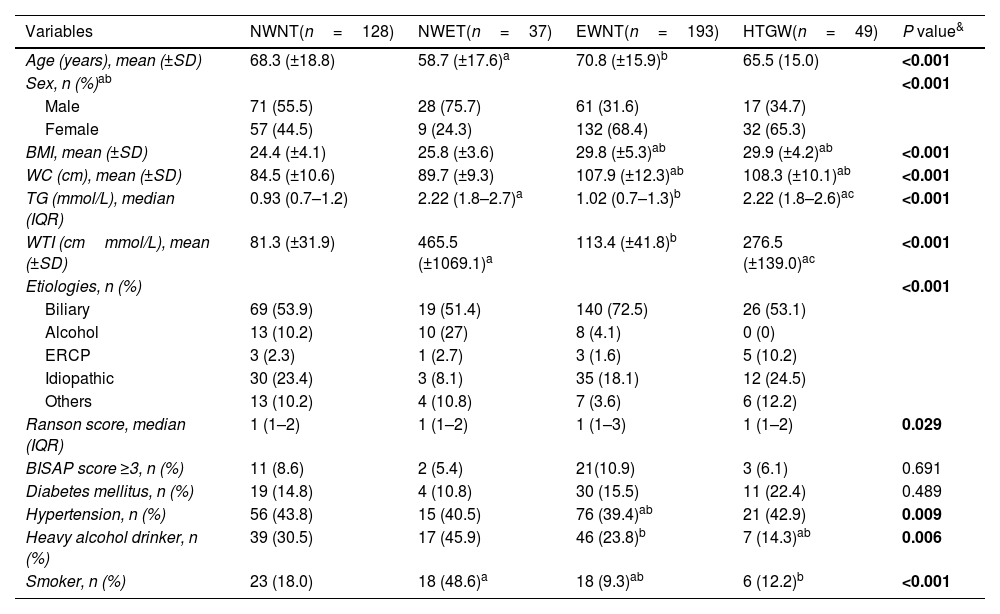

ResultsAmong the 635 patients diagnosed with AP throughout the study period, 407 (64.0%) met the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). Two hundred seven (56.5%) were female. The mean age was 68.3±17.0 years. Regarding lifestyle habits, 16% were smokers and 27.8% drank alcohol. Among the previous chronic diseases, 53.1% had hypertension and 15.7% had diabetes. The most frequent cause of AP among the different phenotypes was biliary (62.4%). Baseline patient and admission characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection. AP: acute pancreatitis; CP: chronic pancreatitis; NWNT: normal waist circumference+normal triglycerides; NWET: normal waist circumference+elevated triglycerides; EWNT: enlarged waist circumference+normal triglycerides; HTGW, enlarged waist circumference+triglycerides.

Patient baseline and clinical characteristics at admission in four phenotypes groups.

| Variables | NWNT(n=128) | NWET(n=37) | EWNT(n=193) | HTGW(n=49) | P value& |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 68.3 (±18.8) | 58.7 (±17.6)a | 70.8 (±15.9)b | 65.5 (15.0) | <0.001 |

| Sex, n (%)ab | <0.001 | ||||

| Male | 71 (55.5) | 28 (75.7) | 61 (31.6) | 17 (34.7) | |

| Female | 57 (44.5) | 9 (24.3) | 132 (68.4) | 32 (65.3) | |

| BMI, mean (±SD) | 24.4 (±4.1) | 25.8 (±3.6) | 29.8 (±5.3)ab | 29.9 (±4.2)ab | <0.001 |

| WC (cm), mean (±SD) | 84.5 (±10.6) | 89.7 (±9.3) | 107.9 (±12.3)ab | 108.3 (±10.1)ab | <0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 0.93 (0.7–1.2) | 2.22 (1.8–2.7)a | 1.02 (0.7–1.3)b | 2.22 (1.8–2.6)ac | <0.001 |

| WTI (cmmmol/L), mean (±SD) | 81.3 (±31.9) | 465.5 (±1069.1)a | 113.4 (±41.8)b | 276.5 (±139.0)ac | <0.001 |

| Etiologies, n (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Biliary | 69 (53.9) | 19 (51.4) | 140 (72.5) | 26 (53.1) | |

| Alcohol | 13 (10.2) | 10 (27) | 8 (4.1) | 0 (0) | |

| ERCP | 3 (2.3) | 1 (2.7) | 3 (1.6) | 5 (10.2) | |

| Idiopathic | 30 (23.4) | 3 (8.1) | 35 (18.1) | 12 (24.5) | |

| Others | 13 (10.2) | 4 (10.8) | 7 (3.6) | 6 (12.2) | |

| Ranson score, median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–3) | 1 (1–2) | 0.029 |

| BISAP score ≥3, n (%) | 11 (8.6) | 2 (5.4) | 21(10.9) | 3 (6.1) | 0.691 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 19 (14.8) | 4 (10.8) | 30 (15.5) | 11 (22.4) | 0.489 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 56 (43.8) | 15 (40.5) | 76 (39.4)ab | 21 (42.9) | 0.009 |

| Heavy alcohol drinker, n (%) | 39 (30.5) | 17 (45.9) | 46 (23.8)b | 7 (14.3)ab | 0.006 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 23 (18.0) | 18 (48.6)a | 18 (9.3)ab | 6 (12.2)b | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: NWNT, normal waist circumference+normal triglycerides; NWET, normal waist circumference+elevated triglycerides; EWNT, enlarged waist circumference+normal triglycerides; HTGW, enlarged waist circumference+triglycerides; BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; TG, triglycerides; WTI, waist triglyceride index; IQR, interquartile range; BISAP, Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis.

The significance for pairwise comparisons was calculated using the Bonferroni adjustment. aP<0.05, compared with NWNT; bP<0.05, compared with the NWET; cP<0.05, compared with EWNT.

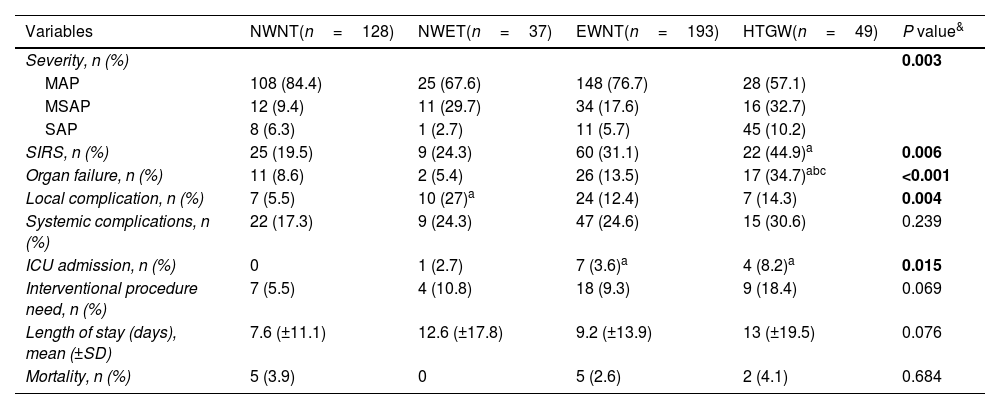

Clinical outcome comparison among phenotype groups is shown in Table 2. Regarding severity of AP, 75.9% presented with mild acute pancreatitis (MAP), 17.9% with moderately severe acute pancreatitis (MSAP), and 6.1% with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP). There was a significant difference in the severity of AP among the phenotype groups. MSAP (32.7%) and SAP (10.2%) were most frequent in the HTGW group. The overall incidence of organ failure was 13.8%, being higher in the HTGW group (34.7%). Forty-eight patients (11.8%) developed local complications, and their incidence was higher in the NWET group. Overall, SIRS developed in 116 (28.5%) patients and was most common among patients in the HTGW group (44.9%). ICU care was required most frequently among patients in the HTGW group (8.2%). There were no significant differences among the groups in terms of systemic complications (P=0.23), interventional procedure need (P=0.07), length of stay (P=0.07) or mortality (P=0.68).

Comparison of clinical outcomes in four phenotypes groups.

| Variables | NWNT(n=128) | NWET(n=37) | EWNT(n=193) | HTGW(n=49) | P value& |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity, n (%) | 0.003 | ||||

| MAP | 108 (84.4) | 25 (67.6) | 148 (76.7) | 28 (57.1) | |

| MSAP | 12 (9.4) | 11 (29.7) | 34 (17.6) | 16 (32.7) | |

| SAP | 8 (6.3) | 1 (2.7) | 11 (5.7) | 45 (10.2) | |

| SIRS, n (%) | 25 (19.5) | 9 (24.3) | 60 (31.1) | 22 (44.9)a | 0.006 |

| Organ failure, n (%) | 11 (8.6) | 2 (5.4) | 26 (13.5) | 17 (34.7)abc | <0.001 |

| Local complication, n (%) | 7 (5.5) | 10 (27)a | 24 (12.4) | 7 (14.3) | 0.004 |

| Systemic complications, n (%) | 22 (17.3) | 9 (24.3) | 47 (24.6) | 15 (30.6) | 0.239 |

| ICU admission, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 7 (3.6)a | 4 (8.2)a | 0.015 |

| Interventional procedure need, n (%) | 7 (5.5) | 4 (10.8) | 18 (9.3) | 9 (18.4) | 0.069 |

| Length of stay (days), mean (±SD) | 7.6 (±11.1) | 12.6 (±17.8) | 9.2 (±13.9) | 13 (±19.5) | 0.076 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 5 (3.9) | 0 | 5 (2.6) | 2 (4.1) | 0.684 |

Abbreviations: NWNT, normal waist circumference+normal triglycerides; NWET, normal waist circumference+elevated triglycerides; EWNT, enlarged waist circumference+normal triglycerides; HTGW, enlarged waist circumference+triglycerides; MAP, mild acute pancreatitis; MSAP, moderately severe acute pancreatitis; SAP, sever acute pancreatitis; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit.

The significance for pairwise comparisons was calculated using the Bonferroni adjustment. aP<0.05, compared with NWNT; bP<0.05, compared with the NWET; cP<0.05, compared with EWNT.

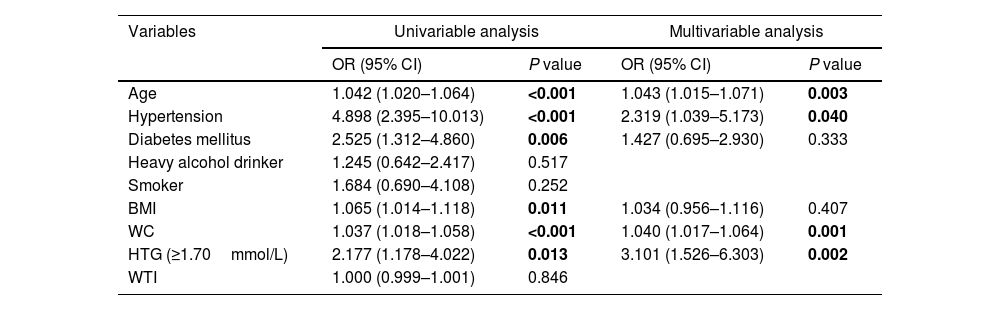

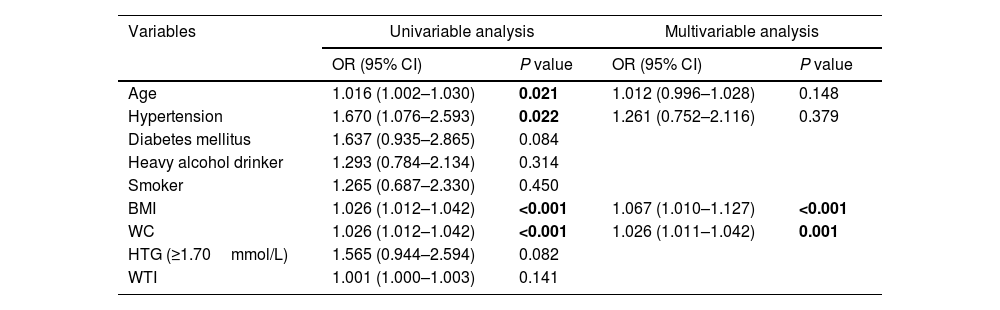

Univariable regression analysis showed that age, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, BMI, WC and HTG were associated with organ failure, and all of them except diabetes and HTG were related to SIRS. On multivariable logistic regression analysis, WC remained a significant predictor, increasing by 4% and 2% the likelihood of developing organ failure (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.06) and SIRS (OR 1.02; 95% CI 1.01–1.04), respectively, for each 1-cm increase in WC. BMI was found to be a risk factor for SIRS (OR 1.06; 95% CI 1.01–1.12). HTG (OR 3.10; 95% CI 1.52–6.30), age (OR 1.04; 95% CI 1.01–1.07) and hypertension (OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.03–5.17) were also predictors of organ failure. The results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of proposed predictors of organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.042 (1.020–1.064) | <0.001 | 1.043 (1.015–1.071) | 0.003 |

| Hypertension | 4.898 (2.395–10.013) | <0.001 | 2.319 (1.039–5.173) | 0.040 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2.525 (1.312–4.860) | 0.006 | 1.427 (0.695–2.930) | 0.333 |

| Heavy alcohol drinker | 1.245 (0.642–2.417) | 0.517 | ||

| Smoker | 1.684 (0.690–4.108) | 0.252 | ||

| BMI | 1.065 (1.014–1.118) | 0.011 | 1.034 (0.956–1.116) | 0.407 |

| WC | 1.037 (1.018–1.058) | <0.001 | 1.040 (1.017–1.064) | 0.001 |

| HTG (≥1.70mmol/L) | 2.177 (1.178–4.022) | 0.013 | 3.101 (1.526–6.303) | 0.002 |

| WTI | 1.000 (0.999–1.001) | 0.846 | ||

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HTG, hypertriglyceridemia; WTI, waist triglyceride index.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of proposed predictors of SIRS in patients with acute pancreatitis.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 1.016 (1.002–1.030) | 0.021 | 1.012 (0.996–1.028) | 0.148 |

| Hypertension | 1.670 (1.076–2.593) | 0.022 | 1.261 (0.752–2.116) | 0.379 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.637 (0.935–2.865) | 0.084 | ||

| Heavy alcohol drinker | 1.293 (0.784–2.134) | 0.314 | ||

| Smoker | 1.265 (0.687–2.330) | 0.450 | ||

| BMI | 1.026 (1.012–1.042) | <0.001 | 1.067 (1.010–1.127) | <0.001 |

| WC | 1.026 (1.012–1.042) | <0.001 | 1.026 (1.011–1.042) | 0.001 |

| HTG (≥1.70mmol/L) | 1.565 (0.944–2.594) | 0.082 | ||

| WTI | 1.001 (1.000–1.003) | 0.141 | ||

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HTG, hypertriglyceridemia; WTI, waist triglyceride index.

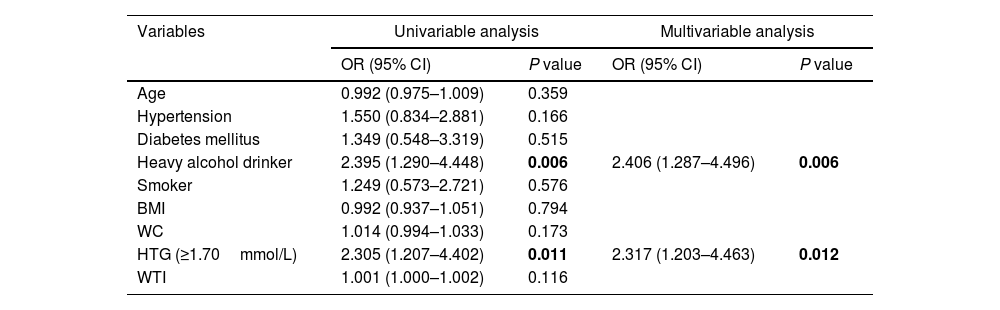

With regard to local complications, HTG (OR 2.31; 95% CI 1.20–4.46) as well as alcoholism (OR 2.40; 95% CI 1.28–4.49) remained independent risk factors for local complications on the multivariable logistic regression analysis (Table 5).

Univariable and multivariable analysis of proposed predictors of local complications in patients with acute pancreatitis.

| Variables | Univariable analysis | Multivariable analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age | 0.992 (0.975–1.009) | 0.359 | ||

| Hypertension | 1.550 (0.834–2.881) | 0.166 | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.349 (0.548–3.319) | 0.515 | ||

| Heavy alcohol drinker | 2.395 (1.290–4.448) | 0.006 | 2.406 (1.287–4.496) | 0.006 |

| Smoker | 1.249 (0.573–2.721) | 0.576 | ||

| BMI | 0.992 (0.937–1.051) | 0.794 | ||

| WC | 1.014 (0.994–1.033) | 0.173 | ||

| HTG (≥1.70mmol/L) | 2.305 (1.207–4.402) | 0.011 | 2.317 (1.203–4.463) | 0.012 |

| WTI | 1.001 (1.000–1.002) | 0.116 | ||

Bold indicates statistical significance.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; WC, waist circumference; HTG, hypertriglyceridemia; WTI, waist triglyceride index.

In our research from a prospective database, it was investigated the effects of WC and HTG on AP severity. The present study demonstrated that the isolated HTG phenotype exhibited the most significant association with local complications. On the other hand, a significantly high incidence of SIRS was linked with both the HTGW and EWNT groups. Nevertheless, this relationship was more significant for the HTGW group. In addition, ICU need was most frequent in the HTGW (8.2%).

Several studies have reported that HTG is related to a high incidence of SAP. This can be explained by the fact that in the setting of AP, high levels of TG are hydrolyzed into free fatty acids by pancreatic lipase, which exceeds the capacity of the regulatory mechanisms. The excess of free fatty acids causes direct tissue injury (lipotoxicity) and pancreatic capillary damage. In addition, an upregulation of cytokines induced by high levels of TG leads to an intense inflammatory response causing multiple organ failure.8,21–23

The current study found that the incidence of SIRS was higher in the HTGW, which is in line with the study from Ding et al.4 However, TG levels had no statistical significance in the multivariable analysis, which suggests that the enlarged WC is what could be related to SIRS in this group of patients instead of high levels of TG. On the other hand, we found that patients with HTG had higher incidences of organ failure and local complications. These findings are consistent with those of Hidalgo et al. and Kiss et al., who reported that high levels of TG were independently associated with pancreatic necrosis and organ failure.24,25

This study has shown that the enlarge WC remained a significant predictor of organ failure and SIRS in the adjusted model. These findings were consistent with two previous studies conducted at Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición “Salvador Zubiran” in Mexico, which demonstrated that abdominal adiposity according to WC is associated with an increased risk of multiple organ failure.7,26 WC is the most accurate surrogate marker of visceral adiposity and an easy index to obtain.27 Low levels of adiponectin, which inhibits macrophage production of tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6, have been linked to visceral adiposity. Consequently, the high levels of these cytokines lead to an amplified inflammatory response, increasing the severity of AP.6

There are several limitations in the current study that need to be considered. First, there might be potential confounders that were not measured but may influence the present associations. Second, this study was carried out in a single center, and most of the patients came from the same geographical area. Therefore, caution should be taken at the moment of generalizing the present results to other populations. Third, TG levels were measured 24h after admission since this measurement is not routinely performed at emergency room. This delay in the measurement might lead to bias because most patients with AP are treated by fasting during the first hours of hospitalization, resulting in a fall in TG levels. This fact has been observed in previous studies.25,28–30 Due to those limitations, we suggest carrying out multicenter, prospective studies in order to corroborate the results of the present study.

In summary, our retrospective study found that HTGW and isolated enlarged WC phenotypes were significantly related to the development of SIRS. It seems that an enlarged WC has a greater role than HTG in the development of SIRS in these patients. The need for admission to the ICU was higher in the HTGW phenotype. Moreover, an enlarged WC and HTG were independent risk factors for organ failure. Patients with HTG were more likely to develop local complications. The previous findings suggest that the measurement of WC and TG levels seems to be helpful in identifying high-risk patients with AP on admission.

Authors’ contributionsInvolved in the conception, analysis of data and draft of the manuscript: JFPG and RCZI. Involved in the acquisition of data: MLRR and MARR. Revised manuscript critically for important intellectual content: MLRR and LFS. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

FundingNone declared.

Conflict of interestNo potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.