The population of Latin America harbors the highest incidence of gallstones and acute biliary pancreatitis, yet little is known about the initial management of acute pancreatitis in this large geographic region.

Participants and methodsWe performed a post hoc analysis of responses from physicians based in Latin America to the international multidisciplinary survey on the initial management of acute pancreatitis. The questionnaire asked about management of patients during the first 72h after admission, related to fluid therapy, prescription of prophylactic antibiotics, feeding and nutrition, and timing of cholecystectomy. Adherence to clinical guidelines in this region was compared with the rest of the world.

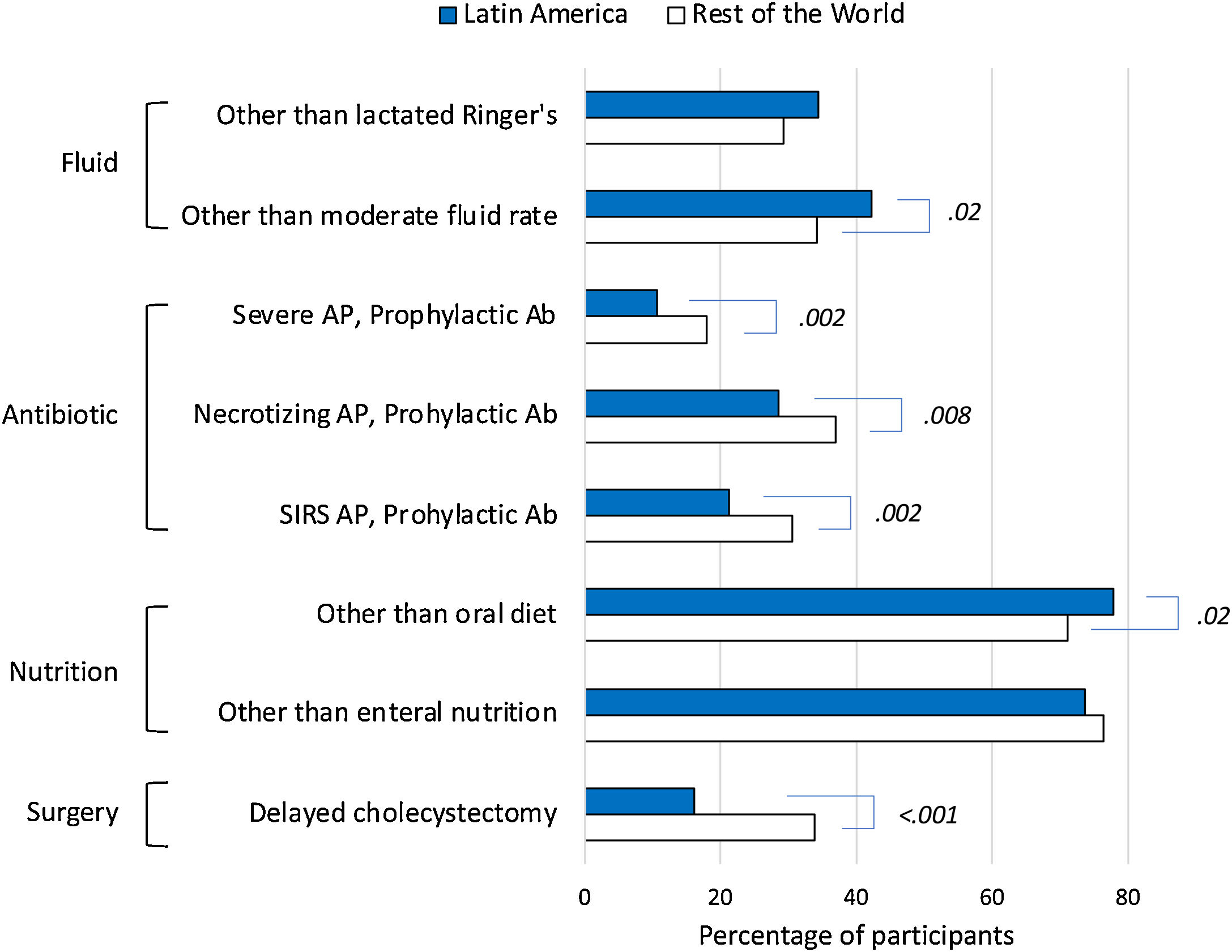

ResultsThe survey was completed by 358 participants from 19 Latin American countries (median age, 39 years [33–47]; women, 27.1%). The proportion of participants in Latin America vs. the rest of the world who chose non-compliant options with clinical guidelines were: prescription of fluid therapy rate other than moderate (42.2% vs 34.3%, P=.02); prescription of prophylactic antibiotics for severe (10.6% vs 18.0%, P=.002), necrotizing (28.5% vs 36.9%, P=.008), or systemic inflammatory response syndrome-associated (21.2% vs 30.6%, P=.002) acute pancreatitis; not starting an oral diet to patients with oral tolerance (77.9% vs 71.1%, P=.02); and delayed cholecystectomy (16.2% vs 33.8%, P<.001).

ConclusionsSurveyed physicians in Latin America are less likely to prescribe antibiotics and to delay cholecystectomy when managing patients in the initial phase of acute pancreatitis compared to physicians in the rest of the world. Feeding and nutrition appear to require the greatest improvement.

La población de América Latina alberga la mayor incidencia de cálculos biliares y pancreatitis biliar aguda, sin embargo, poco se sabe sobre el manejo inicial de la pancreatitis aguda en esta extensa región geográfica.

Participantes y métodosSe realizó un análisis post hoc de las respuestas de los médicos de América Latina a la encuesta internacional multidisciplinar sobre el tratamiento inicial de la pancreatitis aguda. En el cuestionario se preguntaba por el manejo de los pacientes durante las primeras 72 h tras el ingreso, en relación con la fluidoterapia, la prescripción de antibióticos profilácticos, la alimentación y nutrición y el momento de la colecistectomía. La adherencia a las guías clínicas en esta región se comparó con la del resto del mundo.

ResultadosLa encuesta fue completada por 358 participantes de 19 países latinoamericanos (mediana de edad, 39 años [33-47]; mujeres, 27,1%). La proporción de participantes de América Latina frente al resto del mundo que eligieron opciones no conformes con las guías clínicas fueron: prescripción de fluidoterapia en casos distintos de los moderados (42,2 vs. 34,3%, p = 0,02); prescripción de antibióticos profilácticos en casos graves (10,6 vs. 18%, p = 0,002); necrotizante (28,5 vs. 36,9%, p = 0,008) o asociada al síndrome de respuesta inflamatoria sistémica (21,2 vs. 30,6%, p = 0,002); no inicio de dieta oral en pacientes con tolerancia oral (77,9 vs. 71,1%, p = 0,02); y retraso de la colecistectomía (16,2 vs. 33,8%, p < 0,001).

ConclusionesLos médicos encuestados en América Latina son menos propensos a prescribir antibióticos y a retrasar la colecistectomía cuando tratan a pacientes en la fase inicial de la pancreatitis aguda, en comparación con los médicos del resto del mundo. La alimentación y la nutrición parecen requerir las mayores mejoras.

Latin America is generally understood to consist of South America, Central America, Mexico and the Caribbean, whose inhabitants speak a Romance language derived from Latin. The worldwide prevalence of gallstone disease, based on ultrasound studies and cholecystectomies, is highest in Latin America, where Indian ethnicity, female gender, obesity, and age are associated with additional risk of gallstone formation.1

The incidence of acute pancreatitis has increased in recent decades in the Western world,2 and specifically in Latin America. In the 2010s, the incidence of acute pancreatitis in Chile was between 39 and 43.7 episodes/100,000 inhabitants, although it reached 53.6 in aboriginal ethnic groups, probably associated with a higher incidence of biliary disease.3 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis4 with data from Argentina, Chile, Mexico, Jamaica and Paraguay, showed that acute biliary pancreatitis was consistently more frequent in Latin American countries than in any other world region. Specifically, biliary etiology was the cause of 42% (95% CI, 39–44) of all episodes of acute pancreatitis in the world, and increased to 68% (95% CI, 57.6–78.3) in Latin America.4 According to the APPRENTICE registry, which included data from Mexico, Paraguay and Argentina, patients with acute pancreatitis in the region were mostly young (median age 43 years, IQR 29–59) and female (67%).5 Considering all the above, it seems that the incidence, etiology and characteristics of the patients experiencing episodes of acute pancreatitis are different in the population of Latin America compared to the rest of the world.

To date, surveys of Latin American physicians exploring their approach to the initial management of patients with acute pancreatitis are based on the opinion of few participants from localized geographic areas. Thus, only two recent international surveys included six6 and thirteen7 physicians from Latin America, respectively, while a survey of seventy-four physicians focused on four hospitals in Veracruz, Mexico.8 In this regard, we have recently completed the largest international survey of physicians from around the world on the initial management of acute pancreatitis,9 which included participants evenly distributed from Latin American countries. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to analyze the survey data provided by these Latin American physicians, in order to guide improvement strategies on fluid therapy, antibiotics, feeding and nutrition, and timing of cholecystectomy targeted to this unique region, and to compare their performance with the rest of the world.

Participants and methodsStudy designThe present study is a post hoc secondary analysis of the data collected in the International Multidisciplinary survey on the initial management of Acute Pancreatitis (IMAP) designed to find point-of care decisions that differ from clinical guidelines recommendations.9 The questionnaire and global analysis of the data has been published elsewhere.9 Briefly, it included questions to characterize the professional profile of the participants, and the strategies they currently used to manage patients with acute pancreatitis during the first 72h after admission, related to fluid therapy, prescription of prophylactic antibiotics, feeding and nutrition, and timing of cholecystectomy. The clinical practice guidelines endorsed by the American Gastroenterological Association Institute10 and the World Society of Emergency Surgery11 were used as reference. The questionnaire was accessible on REDCap12 via the link provided through scientific societies and social media (Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn); no registration or password required. The survey was distributed online between May and August 2021. This was an anonymous survey. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante (CEIm PI2022-089) approved the study design and waived informed consent from the participants.

Data analysisDescriptive statistics was used for demographic and professional characteristics of participants. Quantitative variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR), and categorical variables as absolute and relative frequencies. Differences between groups of participants were compared using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical data, the T-test for parametric quantitative data, and the Mann–Whitney U test for quantitative non-parametric data. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression was used to determine whether there was an association between demographic and professional characteristics of participants and their answers to questions related to fluid therapy, use of prophylactic antibiotics, nutrition, and cholecystectomy. Correct responses were selected in accordance with the recommendations provided in the clinical guidelines. The characteristics corresponding to the highest proportion of participants in each domain (i.e., fully trained participants in the career domain) were selected as a reference. P values of less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using RStudio, version 1.2.5001 (Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA, USA). Planning and analysis of the study was carried out according to the AAPOR Reporting Guidelines for Survey Studies.13

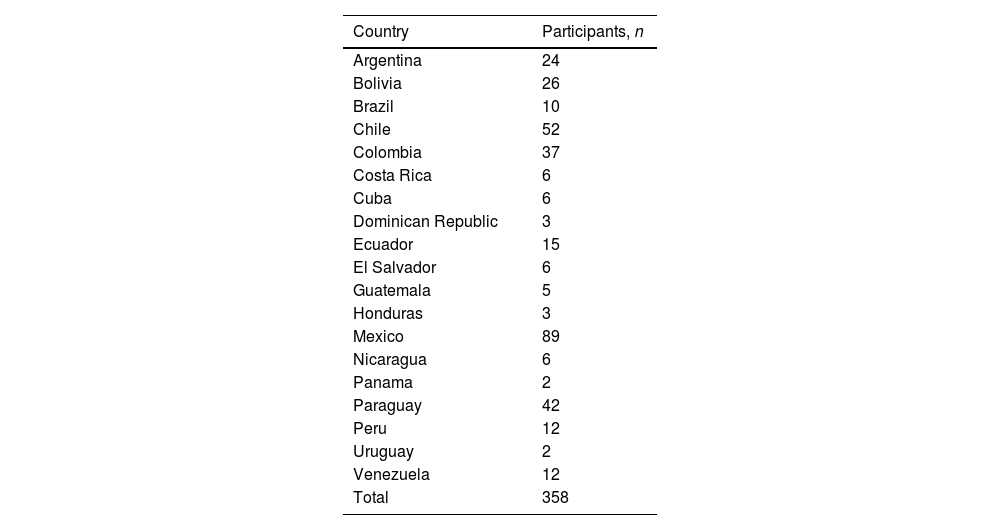

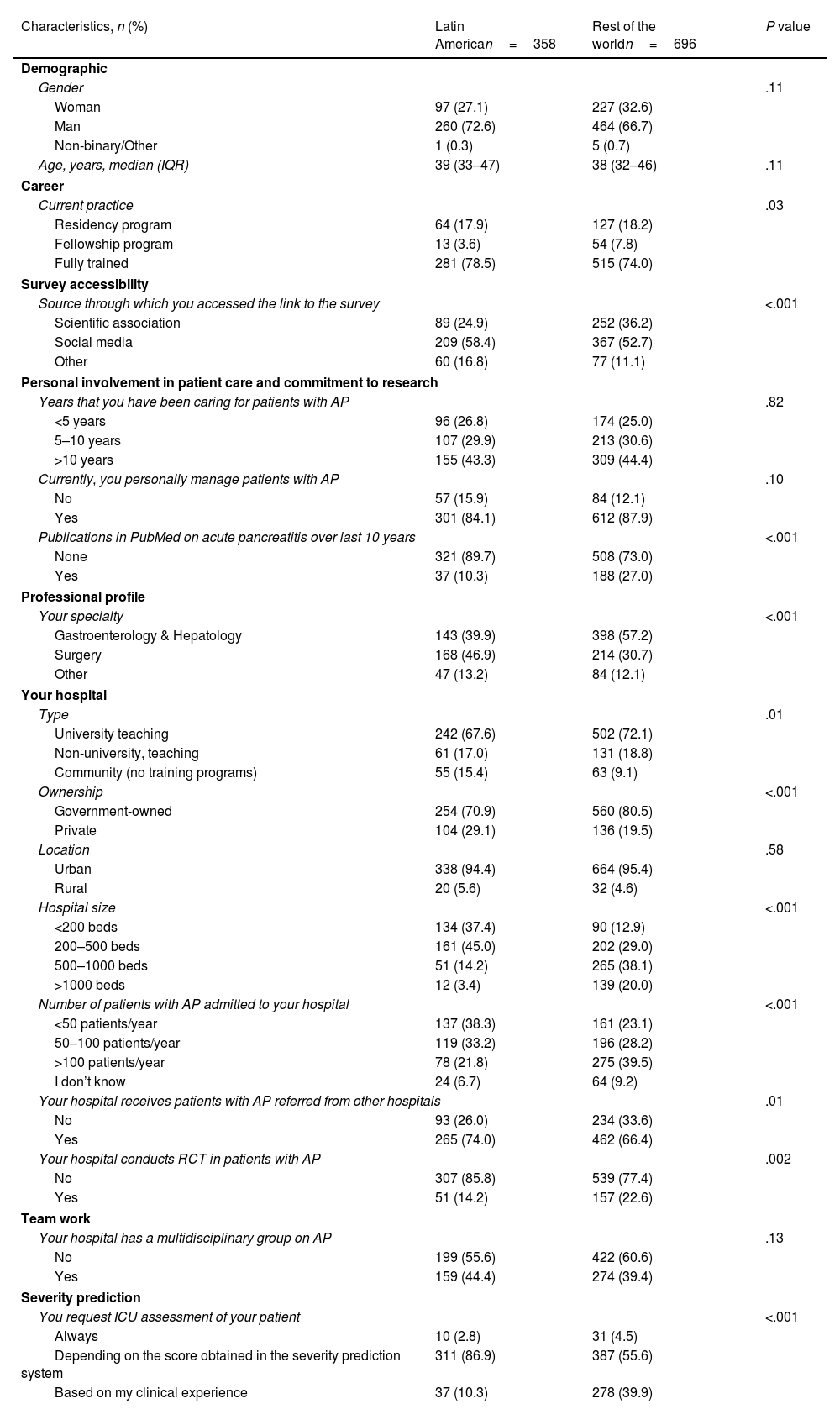

ResultsDemographic and professional characteristics of participantsA total of 358 participants from 19 Latin American countries (median of 10 participants/country, IQR 5–25) and 696 participants from the rest of the world completed the survey (Table 1). Median age of participants from Latin America was 39 years (33–47), women 27.1%; median age of participants from the rest of the world was 38 years (32–46), women 32.6% (P=.11). Aside from demographics, participants from Latin America differed from those from the rest of the world (Table 2). More participants from Latin American countries accessed the survey through social media (58.4% vs 52.7%, P<.001), were surgeons (46.9% vs 30.7%, P<.001), and fully trained (78.5% vs 74.0%, P=.03). In contrast, fewer participants had PubMed publications (10.3% vs 27.0%, P<.001). On the other hand, more participants practiced their profession in community hospitals (15.4% vs 9.1%, P=.01), private hospitals (29.1% vs 19.5%, P<.001), hospitals with fewer beds (P<.001), hospitals that admitted fewer patients with acute pancreatitis per year (P<.001), and hospitals that received more patients with acute pancreatitis referred from other hospitals (74.0% vs 66.4%, P<0.1). However, fewer hospitals were conducting randomized controlled trials (14.2% vs 22.6%, P=.002). Lastly, a higher proportion of participants requested ICU assessment depending on the severity prediction system (86.9% vs 55.6%, P<.001). Additional characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Participants who completed the survey by Latin American country.

| Country | Participants, n |

|---|---|

| Argentina | 24 |

| Bolivia | 26 |

| Brazil | 10 |

| Chile | 52 |

| Colombia | 37 |

| Costa Rica | 6 |

| Cuba | 6 |

| Dominican Republic | 3 |

| Ecuador | 15 |

| El Salvador | 6 |

| Guatemala | 5 |

| Honduras | 3 |

| Mexico | 89 |

| Nicaragua | 6 |

| Panama | 2 |

| Paraguay | 42 |

| Peru | 12 |

| Uruguay | 2 |

| Venezuela | 12 |

| Total | 358 |

Demographic and professional characteristics of participants in Latin America and rest of the world.

| Characteristics, n (%) | Latin American=358 | Rest of the worldn=696 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Gender | .11 | ||

| Woman | 97 (27.1) | 227 (32.6) | |

| Man | 260 (72.6) | 464 (66.7) | |

| Non-binary/Other | 1 (0.3) | 5 (0.7) | |

| Age, years, median (IQR) | 39 (33–47) | 38 (32–46) | .11 |

| Career | |||

| Current practice | .03 | ||

| Residency program | 64 (17.9) | 127 (18.2) | |

| Fellowship program | 13 (3.6) | 54 (7.8) | |

| Fully trained | 281 (78.5) | 515 (74.0) | |

| Survey accessibility | |||

| Source through which you accessed the link to the survey | <.001 | ||

| Scientific association | 89 (24.9) | 252 (36.2) | |

| Social media | 209 (58.4) | 367 (52.7) | |

| Other | 60 (16.8) | 77 (11.1) | |

| Personal involvement in patient care and commitment to research | |||

| Years that you have been caring for patients with AP | .82 | ||

| <5 years | 96 (26.8) | 174 (25.0) | |

| 5–10 years | 107 (29.9) | 213 (30.6) | |

| >10 years | 155 (43.3) | 309 (44.4) | |

| Currently, you personally manage patients with AP | .10 | ||

| No | 57 (15.9) | 84 (12.1) | |

| Yes | 301 (84.1) | 612 (87.9) | |

| Publications in PubMed on acute pancreatitis over last 10 years | <.001 | ||

| None | 321 (89.7) | 508 (73.0) | |

| Yes | 37 (10.3) | 188 (27.0) | |

| Professional profile | |||

| Your specialty | <.001 | ||

| Gastroenterology & Hepatology | 143 (39.9) | 398 (57.2) | |

| Surgery | 168 (46.9) | 214 (30.7) | |

| Other | 47 (13.2) | 84 (12.1) | |

| Your hospital | |||

| Type | .01 | ||

| University teaching | 242 (67.6) | 502 (72.1) | |

| Non-university, teaching | 61 (17.0) | 131 (18.8) | |

| Community (no training programs) | 55 (15.4) | 63 (9.1) | |

| Ownership | <.001 | ||

| Government-owned | 254 (70.9) | 560 (80.5) | |

| Private | 104 (29.1) | 136 (19.5) | |

| Location | .58 | ||

| Urban | 338 (94.4) | 664 (95.4) | |

| Rural | 20 (5.6) | 32 (4.6) | |

| Hospital size | <.001 | ||

| <200 beds | 134 (37.4) | 90 (12.9) | |

| 200–500 beds | 161 (45.0) | 202 (29.0) | |

| 500–1000 beds | 51 (14.2) | 265 (38.1) | |

| >1000 beds | 12 (3.4) | 139 (20.0) | |

| Number of patients with AP admitted to your hospital | <.001 | ||

| <50 patients/year | 137 (38.3) | 161 (23.1) | |

| 50–100 patients/year | 119 (33.2) | 196 (28.2) | |

| >100 patients/year | 78 (21.8) | 275 (39.5) | |

| I don’t know | 24 (6.7) | 64 (9.2) | |

| Your hospital receives patients with AP referred from other hospitals | .01 | ||

| No | 93 (26.0) | 234 (33.6) | |

| Yes | 265 (74.0) | 462 (66.4) | |

| Your hospital conducts RCT in patients with AP | .002 | ||

| No | 307 (85.8) | 539 (77.4) | |

| Yes | 51 (14.2) | 157 (22.6) | |

| Team work | |||

| Your hospital has a multidisciplinary group on AP | .13 | ||

| No | 199 (55.6) | 422 (60.6) | |

| Yes | 159 (44.4) | 274 (39.4) | |

| Severity prediction | |||

| You request ICU assessment of your patient | <.001 | ||

| Always | 10 (2.8) | 31 (4.5) | |

| Depending on the score obtained in the severity prediction system | 311 (86.9) | 387 (55.6) | |

| Based on my clinical experience | 37 (10.3) | 278 (39.9) | |

The responses of the participants from Latin America are presented in Fig. 1. The correct responses according to the guidelines are indicated in the Supplementary Table 5. A third of participants (34.4%) would use a fluid other than lactated Ringer's, and a higher proportion of participants (42.2%) would prescribe a rate other than moderate for initial fluid resuscitation. Faced with a patient with severe acute pancreatitis, acute necrotizing pancreatitis, or acute pancreatitis associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), 10.6%, 28.5%, and 21.2% of participants, respectively, would choose to prescribe prophylactic antibiotics. Most of the participants would not start an oral diet in a patient with oral tolerance (77.9%), or an enteral diet in a patient with oral intolerance (73.7%). In contrast, only a minority of participants (16.2%) would delay cholecystectomy or recommend it after a second episode of acute pancreatitis. Additional data is detailed in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6, and Supplementary Fig. 1.

Sunburst chart: responses of Latin American participants to questions raised in clinical cases. Dark colors on each slice indicate the percentages of responses for each item that were non-compliant with the guideline recommendations. Forest plots: Multivariable analysis of demographic and professional characteristics associated with responses of participants to questions raised in clinical cases. No associations were found in responses related to oral intolerance. AP: acute pancreatitis. Ab: antibiotics. SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome. EN: enteral nutrition.

The survey detected differences in the responses to clinical management questions of participants from Latin America and the rest of the world (Fig. 2). The proportion of participants who would prescribe a fluid therapy rate other than moderate was higher in Latin America (42.2% vs 34.3%, P=.02). In contrast, the proportion of participants who would prescribe prophylactic antibiotics was consistently lower in Latin America for severe acute pancreatitis (10.6% vs 18.0%, P=.002), acute necrotizing pancreatitis (28.5% vs 36.9%, P=.008), and acute pancreatitis with SIRS (21.2% vs 30.6%, P=.002). However, a higher proportion of participants would not recommend starting an oral diet to a patient who has oral tolerance (77.9% vs 71.1%, P=.02). Interestingly, a much smaller proportion of participants would delay cholecystectomy (16.2% vs 33.8%, P<.001).

Percentage of participants who would not meet clinical guideline recommendations for fluid therapy, antibiotic use, diet and nutrition, and timing of cholecystectomy in Latin America compared to the rest of the world. AP, acute pancreatitis; Ab, antibiotics; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Absence of P value label means differences were not statistically significant.

However, there was no difference when all items were considered as a whole. The degree of compliance was good/excellent (meaning 5–8 matching responses) in 65.4% of participants from Latin America and in 60.6% of participants from the rest of the world. It was poor/moderate (0–4 matching responses) in the remaining 34.6% of participants from Latin America and 39.4% of participants from the rest of the world (P=.15).

Characteristics associated with non-compliance with clinical guidelinesMultivariable analysis identified demographic and professional characteristics associated with noncompliance with clinical guideline recommendations (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 7–15). Participants from hospitals with>500 beds, and hospitals not receiving referrals from other centers were associated with 113% and 84% increased odds, respectively, of administering a fluid other than lactated Ringer's. Participants with less than 5 years caring for patients with acute pancreatitis, gastroenterologists and hepatologists were associated with 49% and 61% increased odds, respectively, of prescribing a fluid rate other than moderate. Female participants and residents were associated with 121% and 147% increased odds, respectively, of prescribing prophylactic antibiotics in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. Similarly, female participants and residents were associated with 92% and 119% increased odds, respectively, of prescribing prophylactic antibiotics in necrotizing acute pancreatitis. Participants who did not personally care for patients were associated with 229% increased odds of prescribing prophylactic antibiotics in patients with SIRS. Participants>39 years of age were associated with 141% increased odds of choosing nil per os or parenteral nutrition. Participants in training as residents, and those in a multidisciplinary group were associated with 135% and 113% increased odds, respectively, of recommending delayed cholecystectomy or after a second episode of acute pancreatitis.

DiscussionIn summary, when responses to all patient management items were considered together, the degree of compliance with clinical guidelines was poor and similar for participants from Latin America and the rest of the world. However, when items were considered individually, participants from Latin America would use fewer prophylactic antibiotics regardless of the modality of acute pancreatitis (severe, necrotizing, or associated with SIRS), but were less likely than participants from the rest of the world to start an oral diet in a patient with oral tolerance. Undoubtedly, where the participants from Latin America showed better adherence to the clinical guidelines than the rest of the world was in the timing of cholecystectomy. Finally, the findings of the multivariable analysis served as a guide to further improve adherence to clinical guidelines in Latin America.

We searched for studies written in English, Spanish and Portuguese on acute pancreatitis, conducted in Latin America, and cited in PubMed during the last decade to evaluate how these results compare with those published in the literature. There are few published data on fluid type and rate of administration in the early phase of acute pancreatitis coming from Latin America. According to the APPRENTICE registry, the amount of fluid administered during the first 24hours to patients with AP ranged 3–3.2L, and lactated Ringer's appeared to be rarely administered (7%) since it was not widely available.5 A survey in Veracruz, Mexico, found that nearly all participants favored generous fluid replacement.8 Data from our survey regarding fluid therapy showed that participants from Latin America would select similar fluids than participants from the rest of the world, but would perform worse in fluid administration rate. It appears, therefore, that both the type and rate of fluid administration are amenable to improvement. Specifically in Latin America, awareness campaigns should ensure that physicians from large hospitals, or those who do not receive patients referred from other centers, use more Ringer's lactate; and that physicians with few years of practice, gastroenterologists and hepatologists use a moderate rate of fluid administration.

Regarding the use of prophylactic antibiotics, the available evidence in Latin America comes from a single-center study and two multicenter studies carried out in the last two decades. In the late 2000s, antibiotic prophylaxis was regularly given to patients with severe AP in a Mexican hospital.14 In the 2010s, no patient with mild AP received antibiotic prophylaxis in a multicenter study in Argentina, compared to 22% of patients with severe AP.15 Finally, antibiotic prophylaxis was given to 35.7% of patients with biliary AP in a Chilean multicenter study.16 According to a recent survey of physicians from four hospitals in Veracruz, Mexico, 15% of participants prescribed antibiotic prophylaxis to patients with AP.8 In contrast, our survey included a few hundreds of physicians from most Latin American countries. Participants in our survey would prescribe prophylactic antibiotics to patients with severe (10.6%), necrotizing (28.5%), and SIRS-associated acute pancreatitis (21.2%), respectively. Although these percentages were significantly lower in Latin America than in the rest of the world, the survey analysis also provided participant-focused avenues for improvement. Specifically, residents-in-training and female physicians should further decrease the use of prophylactic antibiotics.

According to our survey, feeding and nutrition was by far the domain in which point-of-care practice deviated the most from guideline recommendations and is therefore most in need of improvement. That is why it becomes relevant that a multicenter study in Chile16 revealed that early oral refeeding was standard in mild episodes, and a recent randomized study in Mexico showed that immediate oral feeding was well tolerated, safe, and reduced hospital stays.17 Despite this, our survey showed that – similar to the rest of the world – three quarters of physicians in Latin America would not prescribe an oral diet to patients with oral tolerance. Multivariable analysis specifically identified that physicians over 39 years of age should devote additional effort to this improvement. Similarly, our survey found that three quarters of physicians would not use the enteral route to feed patients with oral intolerance, a finding that would be in line with the APPRENTICE registry, according to which enteral nutrition was lower (15.3%) in Latin America than the world average (25.0%).5 In contrast, parenteral or enteral feeding, alone or mixed, was used in moderate-severe and severe episodes in a Chilean study.16 In summary, the survey found that compliance with clinical guidelines regarding feeding and nutrition needs to be greatly improved.

On the contrary, the timing of cholecystectomy was the item with the highest adherence to clinical guidelines in Latin America, where this practice has improved in recent decades. According to a study in the late 2000s, cholecystectomy was performed during index admission in 20.9% of patients with acute pancreatitis in a Chilean hospital.18 A figure that increased to 54% in a multicenter study conducted in Argentina during the 2010s15 and to 60% in Latin America (vs 15% worldwide) according to the APPRENTICE registry.5 In a recent multicenter study in Chile, most cholecystectomies in patients with acute pancreatitis were performed during the index admission.16 Considering these data altogether, an upward trend of physicians in some Latin America countries in favor of early cholecystectomy for patients with acute pancreatitis is observed. Eighty-three percent of participants in our survey recommended cholecystectomy during, or within days of, index admission in patients with mild acute biliary pancreatitis. Only 16.2% of Latin American participants would postpone cholecystectomy compared to 33.8% in the rest of the world. This halving is unlikely to be due to the higher proportion of patients with acute biliary pancreatitis in Latin America, as the survey question specifically referred to a patient who had a mild episode of acute biliary pancreatitis. Moreover, the multivariable analysis identified that the survey participants who were in training as residents, and those who had a multidisciplinary group were potential candidates to further improve this percentage.

Although the number of participants was not in scale with the total population of each country, this survey was a snapshot that included a fairly balanced representation of physicians from Latin America. The anonymous nature of the survey did not quantify the response rate, nor did it prevent possible duplicities or the participation of general people. However, access through both scientific associations and social media may have brought on board a diversity of skilled professionals who rarely contribute to these surveys. On the other hand, the similarity of answers in both accesses suggested that an anomalous use of the questionnaire was unlikely. This is a post hoc study that has its methodological and statistical limitations, so the results should be considered with caution. In any case, the results obtained can serve to generate hypotheses and propose new studies and interventions.

ConclusionsIn Latin America, as in the rest of the world, feeding and nutrition appear to require the greatest improvement when making point-of-care decisions in the initial management of patients with acute pancreatitis. Professionals in Latin America perform better than the rest of the world regarding the prophylactic administration of antibiotics and early cholecystectomy. The adoption of clinical guideline recommendations aims to avoid complications and reduce mortality in a prevalent disease that still lacks a specific treatment.

Ethical considerationsThe Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis, Alicante (CEIm PI2022-089) approved the study design and waived informed consent from the participants.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestNone.