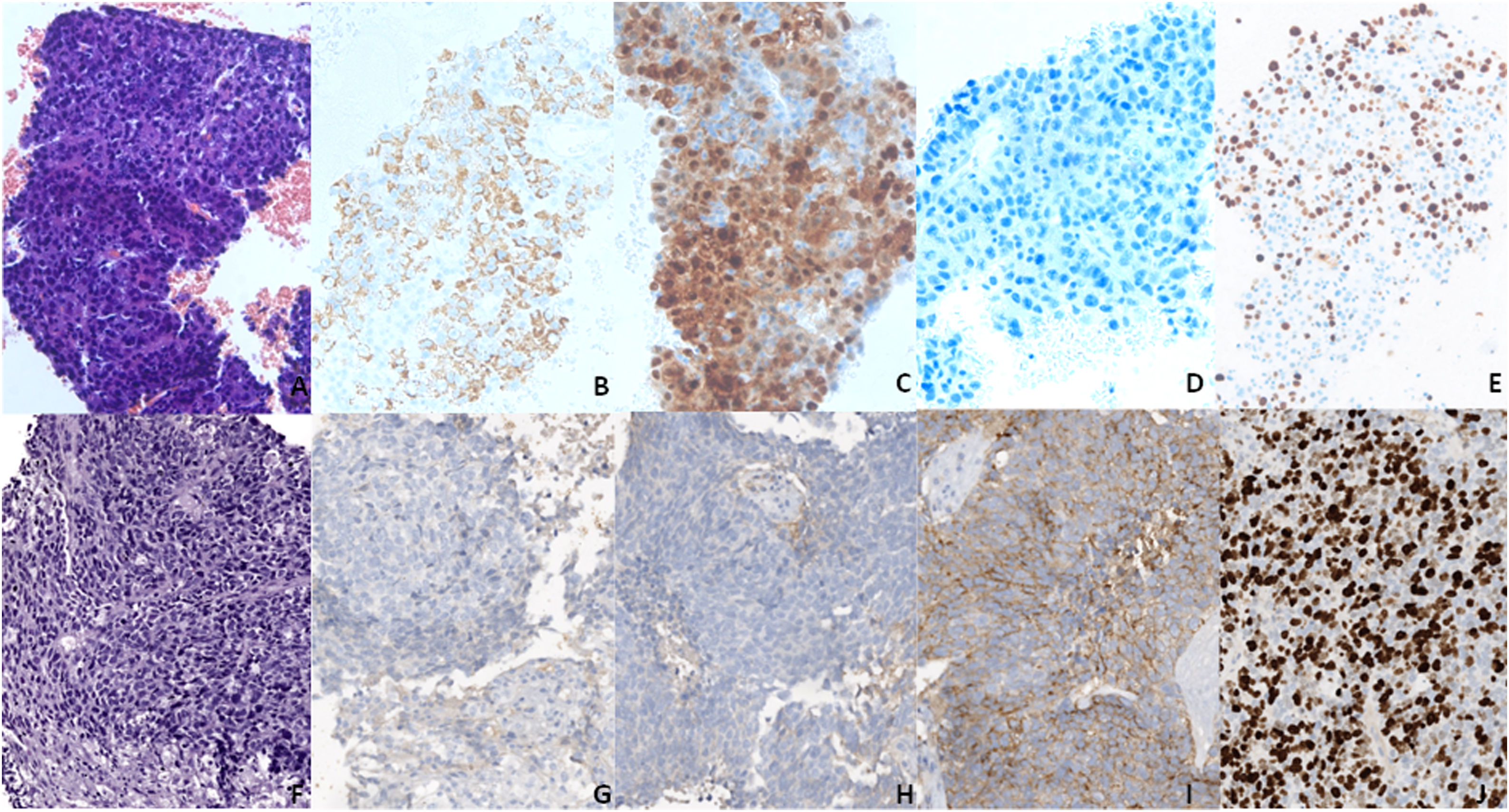

A 75-years old male with history of arterial hypertension, hyperuricemia and liver cirrhosis due to hepatitis C virus infection was successfully treated in 2015 with direct antiviral agents. On October 2018 he was diagnosed by biopsy with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) of 60mm in size in segment VIII. This was associated with vascular invasion of the right and medium hepatic veins (Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage C1) and the patient was included in a randomized controlled first line phase III trial receiving one dose of tremelimumab (anti-CTLA-4) followed by durvalumab (anti-PD-L1) every 4 weeks (NCT03298451). Image assessment at 6 months documented partial response according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours v.1.1 due to size reduction in the target lesion (nadir of 34mm, at month 21) and disappearance of vascular invasion. Furthermore, alpha-fetoprotein decreased from >5000 to 30ng/mL at that time-point. At month 30, progressive disease due to size increase in the target lesion (63mm in size) with invasion of inferior vena cava and of portal vein was observed. Treatment was interrupted and the patient was evaluated for a Second-Line Clinical Trial. Screening included tumor biopsy and the sample was reported as neuroendocrine carcinoma. A second biopsy was undertaken to obtain two tissue samples from two different parts of the nodule. Both tumor biopsies showed similar changes, consistent with an atypical epithelial proliferation arranged in solid nests and with focal central necrosis. The neoplastic cells showed conspicuous atypia, with abundant mitotic figures. Immunohistochemistry showed expression of broad-spectrum cytokeratin as well as neuroendocrine markers (chromogranin, synaptophysin and CD56), with a cell proliferation index (Ki67) of more than 80%. Hepatocytic markers were negative. Thus, the diagnosis of neuroendocrine carcinoma was unequivocally confirmed (Fig. 1). The fine needle biopsy performed in 2018 was also reviewed and the baseline diagnosis of HCC was confirmed, without evidence of neuroendocrine differentiation.

A–E (20×) Block cell from the baseline FNB showing an HCC in H&E (A), with positivity for hepatocyte markers (B, C) and negativity for synaptophysin (D). F–J (20×) Second liver biopsy showing a neuroendocrine carcinoma in H&E (F), with negativity for hepatocyte markers (G, H) and positivity for synaptophysin (I). (E and J) Ki67, showing a proliferation rate above 80% in the biopsy (J), much higher than in FNB (E).

Upon diagnosis establishment the patient was scheduled for systemic therapy with carboplatin plus etoposide for neuroendocrine carcinoma and at the first image assessment a decrease in tumor size was observed.

DiscussionCancer lineage plasticity is a known phenomenon in the oncology realm. It reflects the capacity of a cell to transit into a new and different histological subtype.2 Once it occurs, tumor plasticity generates intra-tumoral heterogeneity, thus playing a crucial role in therapy resistance and in metastatic dissemination.3 In particular, the neuroendocrine transition represents the most known pathway of lineage plasticity in cancer and usually includes the adaptation of adenocarcinomas to more aggressive neuroendocrine phenotypes under therapy.2 Around 5% of EGFR-mutant lung adenocarcinomas, and more than 20% of prostate adenocarcinomas treated with targeted therapies indeed present the transformation into the more aggressive neuroendocrine phenotype.4,5 The current hypothesis of this transition suggests that genetic and epigenetic events promote lineage plasticity and trigger the intra-tumoral heterogeneity.2 Subsequently a plasticity-permissive microenvironment, together with the treatment-exerted selective pressure prime the stem-cell phenotype acquisition and subsequently the transition into the new predominant histological clones.2 Although the pre-treatment presence of scattered neuroendocrine cells into prostate cancer under androgen deprivation therapy has been reported to correlate with poor prognosis, the potential origin of neuroendocrine transition from these cells remains uncertain.

It could be argued that our patient suffered from a false positive result of the initial tumor biopsy, but this is extremely unlikely. First, primary hepatic neuroendocrine tumors and neuroendocrine carcinomas of the liver are rare and HCC with neuroendocrine component are exceptionally rare. Second, in our case the tumor was well represented with the first biopsy so different parts of the nodule were assessed and if the neuroendocrine component would have existed, it could have been detected in the first biopsy.

In conclusion, this case represents the first documented event of neuroendocrine transition in the setting of HCC. This observation is of utmost relevance considering that an immunotherapy-based regimens is included in the current standard of care for the systemic treatment of patients with HCC since 2020 and that the combination of tremelimumab with durvalumab has recently been announced to be superior in comparison to sorafenib in first-line (NCT03298451). Both combinations obtain high rate of objective responses, but upon progression and consideration for Second-Line option, it seems worth to consider a new biopsy to rule out a major change in tumor phenotype that may mandate a completely different treatment approach. Accordingly, we strongly endorse recent tumor biopsy before starting a subsequent line of systemic therapy and even more, when patients are considered for recruitment into research trials.

Ethical considerationsThe study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

FundingMSZ: received grant support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (FI19/00222).

CFA: received grant support from Contractes Clínic de Recerca “Emili Letang-Josep Font” 2020, granted by Hospital Clínic de Barcelona.

JB: received grant support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI18/00768), the Spanish Health Ministry (National Strategic Plan against Hepatitis C), AECC (PI044031) and WCR (AICR) 16-0026.

MR: received grant support from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI15/00145 and PI18/0358) and from the Spanish Health Ministry (National Strategic Plan against Hepatitis C).

CIBERehd: is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.

Conflict of interestMSZ: received speaker fees from Bayer and travel grants from Bayer, BTG and Eisai; JB: has consulted for Arqule, Bayer-Shering Pharma, Novartis, BMS, BTG-Biocompatibles, Eisai, Kowa, Terumo, Gilead, Bio-Alliance, Roche, AbbVie, MSD, Sirtex, Ipsen, Astra-Medimmune, Incyte, Quirem, Adaptimmune, Lilly, Basilea, Nerviano, Sanofi; and received research/educational grants from Bayer, and lecture fees from Bayer-Shering Pharma, BTG-Biocompatibles, Eisai, Terumo, Sirtex, Ipsen; MR: received consultancy fees and/or travel support from Bayer, BMS, Roche, Ipsen, AstraZeneca and Lilly, lecture fees from Bayer, BMS, Gilead, and Lilly and research grants from Bayer and Ipsen; AD: speaker fees from Bayer and travel grants from Bayer.