The purpose of this systematic review was to examine the effect of antipsychotic medication on dysphagia based on clinical case reports.

Patients and methodsLiterature searches were performed using the electronic databases PubMed and Embase. In PubMed, we used the MeSH terms “antipsychotic agents” OR “tranquilizing agents” combined with “deglutition disorders” OR “deglutition”. In Embase, we used the Emtree terms “neuroleptic agents” combined with “swallowing” OR “dysphagia”. Two reviewers assessed the eligibility of each case independently.

ResultsA total of 1043 abstracts were retrieved, of which 36 cases met the inclusion criteria; 14 cases were related to typical antipsychotics and 22 to atypical antipsychotics. Dysphagia occurred together with extrapyramidal symptoms in half of the cases and was the only prominent symptom in the other half. The most common strategy against dysphagia was changing to another antipsychotic (n=13, 36.1%).

ConclusionsThe data from this review indicate that antipsychotics can increase the prevalence of dysphagia.

El propósito de esta revisión sistemática fue examinar el efecto de los fármacos antipsicóticos en la disfagia según los casos clínicos reportados.

Pacientes y métodosLa búsqueda bibliográfica se realizó utilizando las bases de datos electrónicas PubMed y Embase. En PubMed, utilizamos los términos MeSH «agentes antipsicóticos» o «agentes tranquilizantes» combinados con «trastornos de deglución» o «deglución». En Embase, utilizamos los términos de Emtree «agentes neurolépticos» combinados con «deglutir» o «disfagia». Dos revisores evaluaron la elegibilidad de cada caso de forma independiente.

ResultadosSe obtuvieron un total de 1.043 resúmenes, de los cuales 36 casos cumplieron los criterios de inclusión; 14 casos estuvieron relacionados con antipsicóticos típicos y 22 con antipsicóticos atípicos. La disfagia se produjo junto con síntomas extrapiramidales en la mitad de los casos, y fue el único síntoma prominente en la otra mitad. La estrategia más común contra la disfagia fue cambiar a otro antipsicótico (n=13; 36,1%).

ConclusionesLos datos de esta revisión sistemática indican que los antipsicóticos pueden aumentar la prevalencia de la disfagia.

Dysphagia is a symptom that refers to difficulty or discomfort during the progression of the alimentary bolus from the mouth to the stomach.1 From an anatomical standpoint, dysphagia may result from oropharyngeal or esophageal dysfunction and, from a pathophysiological viewpoint, from other structure-related or functional causes.1 The prevalence of oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with dementia ranges from 13% to 84%, depending on subject selection and method, and being higher in more severe phases of the disease.2–4 Its prevalence in Parkinson's disease is 52–82%; it affects up to 84% of patients with Alzheimer's disease, and more than 60% of elderly institutionalized in mental health services.5–7

Dysphagia, or swallowing impairment, can be a result of behavioral, sensory, or motor problems (or a combination).8–10 Medication can also cause dysphagia. It is particularly critical to establish the causality of drug reactions in patient groups at risk of swallowing dysfunctions, such as older people or patients with pre-existing anatomical or functional changes.11 Between medications causing dysphagia, antipsychotic drugs are often misused and overused,12 and in recent years, the inappropriate use of antipsychotics has resulted in several safety concerns.13 To determine the possible association between antipsychotics and the development of swallowing disorders is highly relevant as dysphagia may play a role in antipsychotic-induced pneumonia associated with high mortality rates.14 In recent years, several observational studies have explored the association between antipsychotic use, both typical and atypical, and the risk of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), mainly in older patients.15 Current scientific evidence supports an association between use of antipsychotics in community-dwelling older people and development of CAP in a dose-dependent manner soon after the beginning of treatment.16

Postulated mechanisms of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia include that it can occur as an extrapyramidal adverse reaction, because dopamine blockade can cause dysphagia or laryngospasm.17,18 Moreover, some patients may experience dysphagia in combination with other extrapiramidal symptoms (EPS), whereas in others dysphagia may be the only EPS experienced.17

Populations at risk of drugs causing dysphagia include individuals with neurologic degenerative diseases, dementia, stroke, Parkinson disease, myasthenia gravis and in some mental health patients.18,19 Furthermore, elderly patients may be at increased risk of dysphagia secondary to muscle atrophy, structural changes in the oropharynx, reduced esophageal peristalsis, or cognitive impairment.18–20 Although this group may be more susceptible to the complications associated with dysphagia, it can impact any age group treated with antipsychotics.

The aim of this current systematic literature review is to critically revise the current scientific evidence based on case reports concerning the relationship between antipsychotic use and occurrence of swallowing problems, presenting an overview of the different types of antipsychotics in terms of their negative effects on swallowing function.

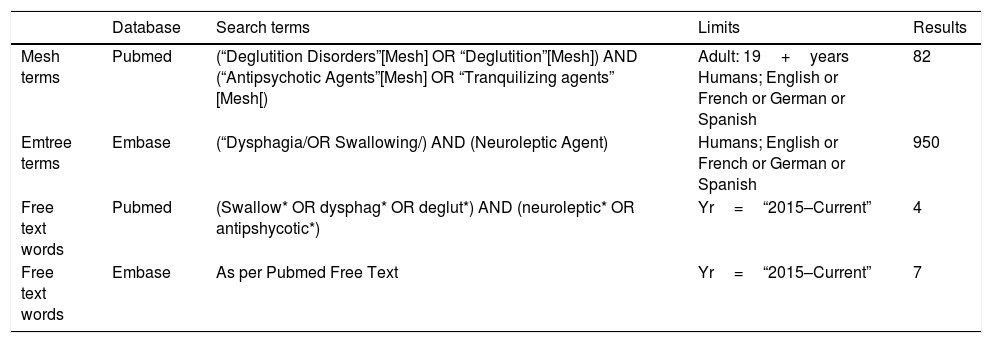

MethodsSearch strategyThe systematic review was conducted in accordance with PRISMA guideline.21 A comprehensive literature search of the electronic databases PubMed and Embase was conducted. All available inclusion studies up to the date of the review (January 2017) were obtained.

Electronic databases were searched using the respective Thesaurus (MeSH or Emtree terms) to link the concept of dysphagia with the concepts of antipsychotics (Table 1). To identify the most recent publications not yet assigned MeSH or Emtree terms, the search was supplemented by using free-text words (truncated) in Embase and PubMed, for the period after January 2015: deglut* or swallow* or dyspha* were combined with neuroleptic* or antipsychotic* (Table 1). The reference lists of all the included articles were searched for additional literature.

Search strategy for Pubmed and Embase.

| Database | Search terms | Limits | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesh terms | Pubmed | (“Deglutition Disorders”[Mesh] OR “Deglutition”[Mesh]) AND (“Antipsychotic Agents”[Mesh] OR “Tranquilizing agents” [Mesh[) | Adult: 19+years Humans; English or French or German or Spanish | 82 |

| Emtree terms | Embase | (“Dysphagia/OR Swallowing/) AND (Neuroleptic Agent) | Humans; English or French or German or Spanish | 950 |

| Free text words | Pubmed | (Swallow* OR dysphag* OR deglut*) AND (neuroleptic* OR antipshycotic*) | Yr=“2015–Current” | 4 |

| Free text words | Embase | As per Pubmed Free Text | Yr=“2015–Current” | 7 |

The search was limited to publications dealing with human adults and in English, German, French and Spanish languages.

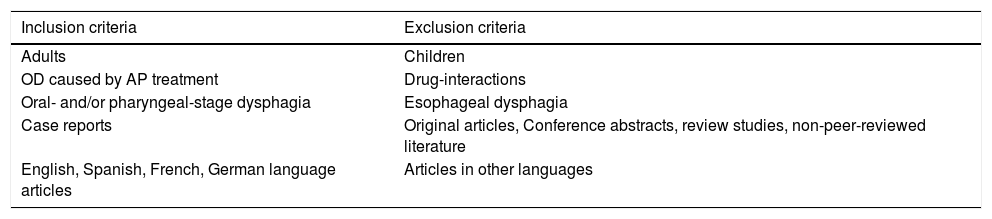

Study selectionThe two authors independently assessed the eligibility of the abstracts in accordance with the inclusion/exclusion criteria described in Table 2. Briefly, all case reports assessing the relationship between antipsychotic treatment and OD in adults and published in English, Spanish, German or French were considered. There were no limitations on disease duration, disease severity or treatment duration.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Adults | Children |

| OD caused by AP treatment | Drug-interactions |

| Oral- and/or pharyngeal-stage dysphagia | Esophageal dysphagia |

| Case reports | Original articles, Conference abstracts, review studies, non-peer-reviewed literature |

| English, Spanish, French, German language articles | Articles in other languages |

The full text of the clinical case reports considered potentially eligible was acquired and the two authors reapplied the inclusion and exclusion criteria independently.

Data extractionA data extraction form was created, piloted, and refined by the first author. The second author reviewed and confirmed extracted data. Data extracted included first author and year of publication, antipsychotic causing the swallowing impairment (including dose and route of administration), neurological and swallowing features, treatment or measures taken to solve the swallowing impairment and clinical outcome. Moreover, data was classified according to whether the antipsychotic was typical or atypical.

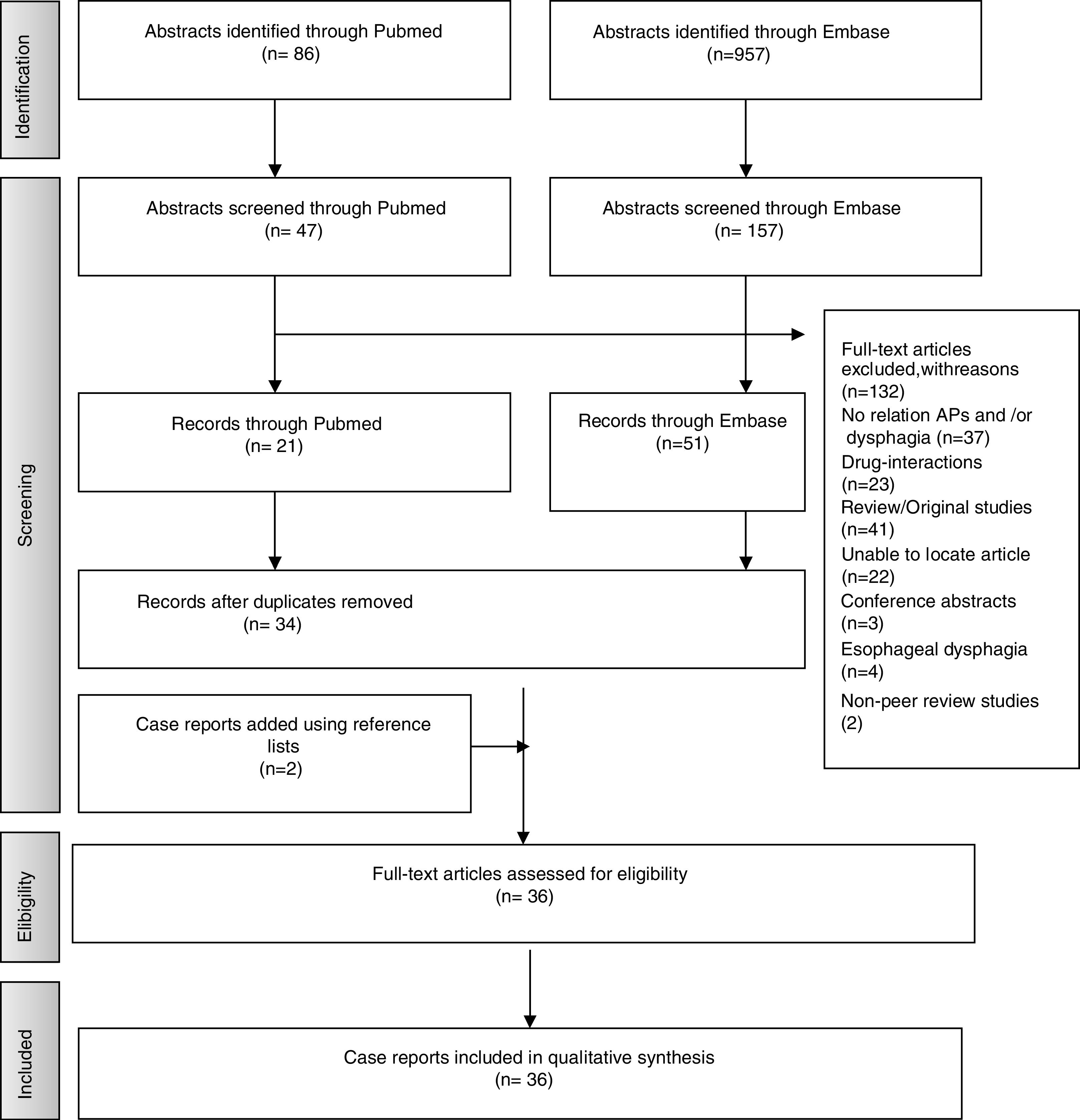

ResultsStudies SelectionA total of 957 articles were selected from Embase and 86 from PubMed. Following application of inclusion criteria regarding article titles and abstracts, consensus was reached on 114 potential articles of which 72 met the inclusion criteria following full text review. Removal of duplicate articles resulted in a total of 33. Three more case reports were added using reference lists resulting in a total of 36 articles. The rest (132) did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria, did not present enough information on study outcomes or the full text was not available. Fig. 1 presents the flow diagram of the reviewing process according to PRISMA.

An overview of the characteristics of the 36 case reports included (one of the articles include two cases) that reflect the effect of antipsychotic medication on deglutition is given in Table 3. The following data are summarized (if reported) for each case report: patient characteristics, antipsychotics causing dysphagia, neurological and dysphagia features, dysphagia assessment method, treatment and clinical outcome.

Case-reports of antipsychotic-induced dysphagia. DA: dysphagia assessment; ENT: ear, nose and throat examination; FOIS: Function Oral Intake Scale Score; MBS: modified barium swallow; NE: neurologic examination; NE: Neurological examination; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

| Author | Patient characteristics | Antipsychotics related to dysphagia | Neurological and dysphagia features | Dysphagia assessment method | Treatment | Clinical outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical antipsychotics | ||||||

| Agarwal et al.22 | 61-year-old man with insomnia | Flupenthixol 0.5mg | NE: involuntary flexion of all fingers of his left hand and developed involuntary, forceful closure of both eyes. No other focal dystonia or parkinsonism, and the rest of the neurological examination was normal. DA: involuntary orolingual movements causing slurring of speech. Intermittent opening of his mouth that cause spillage of food while eating. Difficulty in swallowing solid food. He could swallow only semi-solids or liquids. Three months later, he was completely unable to swallow solids and liquids, necessitating placement of a nasogastric tube. | Clinical assessment | Flupenthixol was tapered and discontinued over 2 weeks. Then started tetrabenazine 50mg (increased 100mg/daily over two weeks), trihexyphenidyl 10mg and clonazepam 1mg daily. | Dysphagia had reduced and he was able to swallow liquids and solids without any difficulty. Dystonia and orobucolingual dyskinesia also improved significantly. |

| Baheshree et al.23 | 28-year-old lady with psychotic symptoms | Chlorpromazine | NE: no abnormalities DA: mild difficulty in swallowing, which progressively worsened up to the point where she had sever dysphagia for both solids and liquids. | Self-reported, ENT evaluation, barium swallow test. | A dose of promethazine did not bring about any improvement. Then, she shifted to risperidone 8mg daily and trihexyphenidyl 2mg daily. | The patient slowly started taking oral fluids. After 2 weeks, she did not have any swallowing difficulty and was able to take food normally. |

| Bashford et al.24 | A 74-year-old woman with a major depressive episode. | Trifluoperazine hydrochloride 2mg twice a day on day 1, and then increased to 5mg twice a day. | NE: Parkinson's disease-like tremor. DA: bedside feeding examination: increased transit time in the oral phase of the swallow, but no delay in reflex swallowing. Normal laryngeal elevation, weak cough reflex. Videofluoroscopic evaluation: the oral phase revealed disorganized oral movements, with reduced bolus formation. Oral transit time was increased to greater than 5seconds. A significant lingual tremor was noted, which impaired this patient's oropharyngeal phase coordination and worsened with solid consistencies. Marked tongue pumping was noted at rest and during lingual propulsion. The swallow reflex was delayed, being triggered at the level of the velum and valleculae. Multiple swallows were required to clear moderate pooling in the valleculae. Pooling was also observed in the pyriform sinuses. Fluid was observed to pass into the pharynx and laryngeal vestibule during oral phase preparation before the swallow reflex was triggered. Laryngeal penetration was observed with the swallowing of puree consistencies. This resulted in silent aspiration, which was not cleared by either involuntary or voluntary cough. | Bedside feeding examination. Videofluoroscopic evaluation (modified barium swallow) | She had modification of consistencies, training in supraglottic swallow, and head positioning. Change or stopping the medication was not possible. | Not provided |

| Bulling et al.25 | 76-year-old man with recurrent depression. | Haloperidol 6mg daily, lithium | NE: no involuntary movements or abnormalities of tone. DA: difficulty starting a swallow with the bolus only reaching as far as the pharynx and then causing cough and expectoration. Impaired pharyngeal peristalsis with significant pooling of barium in the vallecula and piriform fossa and subsequent gross aspiration. Endoscopy showed a non-inflamed segment of Barrett's mucosa 3cm in length and a 1cm slightly fibrotic stricture through which the scope could be easily advanced. | Videofluoroscopy Endoscopy | Cessation of all antipsychotic and antidepressant medication and naso-enteric feeding. | Re-evaluation of his swallowing three weeks after admission showed a marked improvement with no overt signs of audible aspiration. Repeat video barium swallow confirmed that considerable improvement. |

| Chaumartin et al.26 | 28-year-old man with behavioral disorder with homicide on the street. | Loxapine 300mg Increase of loxapine treatment of 450 mg/day to 700mg/day | NE: no extrapyramidal syndrome. DA: dysphagia to solids with choking and regurgitation, aggravated by the increase of loxapine dose. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy shows no anatomical lesion. | Endoscopy. No functional assessment of swallowing was done. | Treatment with loxapine was stopped, and aripiprazole 15mg daily was introduced. | The patient had a very rapid clinical improvement and dysphagia did not reoccur. |

| González et al.27 | 82-year-old woman with insomnia. | Haloperidol 2.5mg daily. | NE: normal DA: dysphagia to solids and liquids. When she attempted to swallow, the liquids would come out through her nose. Oropharyngeal exam revealed an edentulous oral cavity, with no ulcers, lesions or thrush. No gag reflex. No eliciting a response when the physician inserted his index finger and tough the glottis. | Clinical assessment | Administration of subcutaneous injection of diphenydramine 25mg. | Resolved within 30min of injection. She was able to eat bread and drink water. Continue haloperidol at the same dose with no problems since then. |

| Hugues et al.28 | 41-year-old woman with agitated depression with some psychotic features and discoid lupus. | Haloperidol 1.5mg, flupenthixol 20mg every 2 weeks. | NE: cogwheel rigidity and some bradykinesia in the limbs but no other neurological signs. DA: 8-weeks history of worsening, intermittent, painless dysphagia for solids and liquids. Complete failure of laryngeal elevation and closure, and failure of cricopharyngeal opening. Pooling occurred in the pyriform fossae and above the cricopharyngeus, and there was aspiration of contrast into the larynx and trachea. | Videofluoroscopy | Haloperidol was stopped. | Two weeks later she was able to swallow clear fluids. On discharge videofloroscopy showed normal elevation of the larynx and normal opening of the cricopharyngeus without pooling or aspiration. |

| Lee et al.29 | 55-year-old man with a history of traumatic brain injury. | Haloperidol 5mg orally every hour as needed, haloperidol 2mg intravenously every 12h, risperidone 0.25mg orally | NE: EPS, he developed mild rigidity and cogwheeling of his extremities. DA: 5 days after starting haloperidol, development of acute dysphagia, he was unable to ingest oral medications. | Not specified | Haloperidol and risperidone were discontinued, and diphenhydramine 25mg intravenously twice daily was started for extrapyramidal symptoms. | His rigidity and dysphagia improved within a few days of stopping haloperidol. |

| Leopold et al.30 | 38-year-old woman with depression. | Trifluoperazine 5mg daily (11 days treatment) | NE: alert, attentive, slowed hypophonic, monotonic, dysartric speech. Obvious parkinsonian features including moderately severe bradykinesia, akinesia, rigidity of all limbs, and slight postural instability. DA: abnormalities during the pre-esophageal stages of ingestion included a severe reduction of lip and tongue movements, minimal chewing of solids, segmented lingual transfer with moderate posterior lingual leakage for all test substance, decreased velar retraction which delayed bolus transfer, and slow vocal cord adduction with no aspiration or penetration. | Videofluoroscopy using liquids and foods of varying consistence | All medications were withdrawn. | Within 24h, slight improvement of mastication was noted. Also, a daily rapid relief of both parkinsonism and dysphagia, particularly mastication and transfer functions were observed. Three month after discharge no parkinsonism was observed. |

| Nishikawa et al.31 | 42 year-old female with schizophrenia. | Haloperidol 5mg daily. | NE: slight rigidity of her arms. No signs of parkinsonian gait or finger tremor CDA: dysphagia, difficulty in opening her mouth | Not specified | Haloperidol was reduced and an antidepressant was started. | Her EPS persisted for 45 days. Gradually, both her EPS and psychotic symptoms lessened. During 5-year follow-up, she has not shown any sign of oral dyskinesia, psychotic symptoms or parkinsonism. |

| Shinno et al.32 | 75-year old male with adenocarcinoma of the colon and delirium. | Haloperidol 5mg daily (4 days). | NE: over-sedation DA: dysphagia (no more details provided) | Not specified | Haloperidol was discontinued and quetiapine 25mg daily was prescribed. | After quetiapine treatment no adverse effects were present. |

| Sokoloff et al.33 | 79-year-old man with Alzheimer disease. | Loxapine 5mg two times daily (1 week). | NE: not provided DA: chocking on medication. Wet voice. Moderate to severe oral-pharyngeal dysphagia characterized by reduced chewing ability, tongue pumping, defective tongue movements, and reduced base of tongue movement (reduced oral control). Delay in initiating a swallow, pooling of residue in the valleculae and pyriform sinuses, penetration of residue and silent aspiration of thin liquid. | Clinical assessment and Videoflouroscopy | Loxapine was discontinued and chlorpromazine was given in a dose of 10mg every 8h. | One week later a second clinical evaluation indicated an improvement in swallowing with no significant signs of oral or pharyngeal dysphagia. A second videofluoroscopic evaluation one month later, indicated improvement in both the oral and pharyngeal phases. |

| Stones et al.34 | 89-year-old woman with dementia | Fluspirilene 3mg weekly (two months) | NE: left hemiparesis DA: one day of absolute dysphagia. Choking on saliva. | Not specified | Benztropine 2mg intravenously | There was a sustained improvement in her dysphagia. Two months later there had been no recurrence. |

| Tang et al.35 | 46-year-old man with schizophrenia | Flupentixol 20mg intramuscular injection every 2 weeks (for 4 years). | NE: severe involuntary movement such as lateral jaw movement, tongue twisting and limbs tremor and athetoid movement, especially over upper limbs. DA: difficulty in swallowing liquid food initially, and then solid. Episodes of sudden asphyxia at eating. Abnormal bolus holding, piecemeal swallowing, abnormal epiglotic movement, delayed oral transit time in paste barium meal and delayed pharyngeal transit time in all kinds of barium meals, all of which resulted in frequent silent aspirations. | Clinical assessment and Videofluoroscopy | Biperiden 2mg/3 times day was prescribed for a month but achieved no improvement. Amantadine 100mg and Baclofen 5mg daily were prescribed. | Nineteen days later his dysphagia improved much in ingestion of solid foods, but was still present with fluid. Follow-up videofluoroscopy revealed improved paste barium meal oral transit time and aspiration. Baclofen was increased to 5mg twice daily, and both dysphagia and involuntary movement improved 8 days later. |

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||||||

| Armstrong et al.36 | 31-year old woman schizoaffective disorder | Quetiapine 750mg for 2 years. | NE: no evidence of any noticeable extrapyramidal side effects. DA: swallowing difficulty and choking while eating. | Not specified | Stopped medication and changed to aripiprazole 5mg daily. | Swallowing difficulties remitted within 24–48h after stopping quetiapine. Swallowing difficulties have not emerged for the last 10 months. |

| Bhattacharjee et al.37 | 25-year-old male with history of schizophrenia | Olanzapine 10mg daily (3 weeks). | NE: tardive dystonia. DA: difficulty in swallowing intermittently when he attempted to eat solid food. He had no problem in taking liquid. MBS was normal. Lack of normal propulsive activity in pharynx and upper esophagus. Significant residues in the pharynx post-swallow. | Videofluoroscopy | Carbamazepine was started, 200mg three times a day. | After 2 weeks of stating treatment, patient's symptoms improved and he was able to chew and eat solid food without any problem. |

| Brahm et al.38 | 46-year-old woman with dementia due to lithium toxicity and profound mental retardation | Risperidone 2mg daily (increase from 1.5mg to 2mg the previous month), clozapine 500mg. | NE: not provided DA: increase in drooling, difficulty swallowing and gurgling sounds. | Not specified | Risperidone was decreased to 1.5mg daily. | On follow-up 3 days later, drooling and swallowing difficulties were resolving. |

| Duggal et al.39 | 35-year-old woman with paranoid schizophrenia. | Risperidone 4mg daily. | NE: no abnormalities, and no other abnormal movements or extrapyramidal signs. DA: difficulty in swallowing solid and semi-solid food. No difficulty in swallowing liquids, but other kinds of food would tend to get stuck in her throat. Endoscopy and barium swallow study were unremarkable. | Clinical assessment, endoscopy and barium swallow study. | Risperidone was discontinued and she started clozapine 25mg daily, which was increased to 75mg daily over 3 weeks. | She had complete resolution of dysphagia without any additional medications. |

| Kobayashi et al.40 | 68-year-old man with impairment of consciousness. | Quetiapine 50mg daily and amantadine 75mg. | NE: EPS, including “lead pipe” and rigidity. NMS. DA: dysphagia | Not specified | Quetiapine and amantadine were discontinued and dantrolene sodium 20mg daily intravenously and bromocritine 5mg daily were started. | NMS was resolved. |

| Kohen et al.41 | 66-year-old female with bipolar disorder. | Quetiapine 200mg | NE: residual cerebellar symptoms of dysmetria, dysarthria and ataxia DA: Delayed transfer of puree and fluids with aspiration of thick fluids. | Videofluoroscopy | Quetiapine was tapered off. | 1 month later she had a repeat MBS which showed patient improvement. |

| Lin et al.42 | 54-year-old male who presented ritual behavior, irregular life pattern, social withdrawal, self-talking, and poor personal care. | Aripiprazole 10mg daily initially, titrated to 30mg daily within 3 weeks. | NE: no other signs of extrapyramidal symptom, except slight salivary drooling. DA: difficulty in swallowing on the third day of aripiprazole – both solid and semisolid food got stuck in his throat and he could eat only by means of drinking. The function oral intake scale (FOIS) score was four points. | Clinical assessment FOIS | Aripiprazole was tapered to 20mg daily, and trihexyphenidyl 4mg daily was added but swallowing disturbance persisted, so the treatment was changed to paliperidone 6mg daily. | Two days later, he could eat cooked solid foods without difficulty, and his FOIS score progressed to six points. |

| Matsuda et al.43 | 23-year-old woman with auditory hallucinations for 9 years | Aripiprazol 3mg daily initially and then 18mg daily | NE: slurred speech. Gait disturbance. No focal neurological deficit or major abnormality except for postural tremor in her hands. DA: mild dysphagia. Tardive dystonia in the larynx. | Not specified | Aripiprazole was stopped and started quetiapine at 200mg daily, which was titrated to 400mg and maintained. | Her vocal symptoms began to improve a few weeks after admission, continuing thereafter until her vocal and gait disturbance had almost disappeared. After 1 year with quetiapine at 400mg daily her functioning returned to normal. |

| Mellacheruvu et al.44 | 51-year old man with a history of bipolar disorder 21-year-old African American man with acute psychosis and a familiarly history of schizophrenia. | 30mg of ziprasidone intramuscular (IM). 20mg of ziprasidone IM | NE: not provided DA: difficulty speaking and swallowing, and was noted to have stridor. some pooled secretions but no laryngeal edema or macroglossia. NE: not provided DA: he developed trouble swallowing and worsening stridor. | Laryngoscopy Not specified | He was administered 50mg of diphenhydramine hydrochloride IM. He was administered 2mg of cogentin (benztropine) IM. | Within 5min the symptoms had resolved. Later, he was continued on 40mg of oral ziprasidone twice daily and 50mg of oral diphenhydramine hydrochloride twice daily and no further problems were reported. Within several minutes, his symptoms resolved. He was continued on oral ziprasidone of up to 80mg twice daily and 2mg of oral congentin twice daily. The cogentin was tapered over the course of 2 weeks without recurrence of the laryngeal symptoms. |

| Mendhekar et al.45 | 18-year-old man with schizophrenia (DSM-IV-TR criteria), history of being suspicious, irritable, withdrawn, muttering to self, and having grandiose ideas and disturbed biological functions for a duration of 1 year. | Paliperidone 6mg daily, After taking only two doses of paliperidone and within 12h of his last dose, he noted signs of dysphagia | NE: No evidence of organic illness, and no abnormal movements on other parts of the body. DA: chocking sensation in his throat if he tried to ingest any solid or semisolid food and made gurgling sounds. He had little difficulty taking liquids, but solid food would stick in his throat. | Clinical assessment | He was given intramuscular promethazine 50mg and he showed remarkable recovery in swallowing. Paliperidone was replaced by clozapine 200mg daily. | He had no further recurrence of dysphagia. |

| Montañés-Pauls et al.46 | 30-year old woman with severe mental retardation | Risperidone 3mg/daily increased to 6mg/daily. | NE: not provided DA: 5 months after dose increase, difficulty swallowing solid foods and liquids. | Not specified | Not improvement with biperiden 1mg/8h. Stopped risperidone and changed to quetiapine 400mg daily. | The patient improved. |

| Moreno et al.47 | 43 year-old male with Huntington's Disease | Olanzapine 10mg daily. | NE: NMS with severe parkinsonism DA: dysphagia | Not specified | Olanzapine was discontinued. | The patient presented a gradual improvement and two weeks later remained in his basal clinical situation. |

| Nair et al.48 | 35-year old man with schizophrenic relapse. | Risperidone 4mg daily. | NE: not provided DA: difficulty in swallowing. Physical examination revealed remarkable swelling of the uvula without fever. | Self-reported and physical exam. | Risperidone was discontinued. Benztropine 2mg intramuscularly was given. | Within 2h dysphagia disappeared, and there was a dramatic normalization in the size of the uvula. |

| Pearlman et al.49 | 42-year-old man with schizoaffective disorder unresponsive to other APs. | Clozapine 660mg daily (3 months treatment). | NE: not provided DA: hypersalivation and disturbance of swallowing. Normal elevation of the pharynx but retained barium in the vallecular and piriform sinuses, which cleared after several swallows and which suggested decreased pharyngeal peristalsis. | Videofluoroscopy | Benzotropine 2mg was administered and instruction in swallowing two or three times without inhaling were given. | Benztropine had not effect but the instructions in swallowing alleviated the sensation of choking without affecting the sialorrhea. After 9 months, the sialorrhea had abated, despite a dose increase to 900mg/day. |

| Sagar et al.50 | 25-year-old man with bipolar affective disorder. | Olanzapine 20mg | NE: no focal neurologic deficits or signs of parkinsonism. CDA: increased salivation and difficulty in swallowing his saliva and in taking food orally or drinking water. | Not specified | Olanzapine dose was reduced to 10mg daily and was stopped over the next 5 days and the patient was continued on sodium valproate 1000mg and clonazepam 4mg daily. | The dysphagia resolved over the next week. |

| Sico et al.51 | 58-year-old man with psychotic disorder | Risperidone 5mg daily. | NE: intact mental status with no emotional liability. Electromyography/nerve conduction studies showed no evidence of neuropathy, myophaty or motor neuron disease. DA: severe oropharyngeal hypomotility with resultant poor oropharyngeal clearance after swallowing and aspiration. laryngeal aspiration. | Videofluoroscopy | Discontinuation of risperidone | After 9 days he was able to tolerate a soft diet. His bulbar symptoms improved, including return of the gag reflex. One month later, his facial diplegia and dysphagia completely resolved. |

| Stewart52 | 71-year-old man with paranoid schizophrenia. | Intramuscular injection of fluphenazin decanoate 37.5mg and oral fluphenazin up to 20mg daily; dysphagia onset after 4 days. | NE: no parkinsonism DA: normal oral phase, aspiration of thin and thick liquids; pooling of residues in the pyriform sinus. | Videofluoroscopy | Fluphenazin decanoate reduced to 25mg biweekly without additional oral dose. | Normal videofluoroscopy was found after 10 weeks |

| Stewart53 | 76-year-old man with Alzheimer's disease and aggressive behavior | Risperidone 1.5mg daily; dysphagia and parkinsonism noted after 3 months | NE: Mild parkinsonism (mild rigidity, decrement in stride length) DA: poor bolus control; delayed initiation of the pharyngeal phase, decreased and slowed laryngeal elevation, poor laryngeal closure. | Videofluoroscopy | Treatment changed to olanzapine 2.5mg daily. | Parkinsonism resolved within 10 days and normal videofluoroscopy was found after 6 months |

| Varghese et al.54 | 38-year-old man with schizophrenia. | Risperidone 4mg daily (6 months). | NE: no signs of parkinsonism. CDA: difficulty in swallowing food and water. | Self-reported | Reduction of the Risperidone dose from 4mg to 3mg | The patient had significant reduction in his dysphagia. |

| Vohra et al.55 | 40-year old female with bipolar affective disorder and moderate to severe learning disability. | Quetiapine 300mg daily increased to 750mg daily | NE: not provided CDA: symptoms of dysphagia after two weeks of dose increment. | Clinical assessment and videofluoroscopy | Quetiapine was gradually substituted with olanzapine. | Dysphagia disappeared completely and has not reoccurred since then. |

| Yamashita et al.56 | 50-year-old man with a 21-year history of chronic schizophrenia | Risperidone long-acting injection 37.5mg every 2 weeks, levomepromazine 30mg daily. | NE: NMS CDA: difficulty in swallowing, decreasing his oral intake. | Self-reported | Oral biperiden, 2mg, was given, but NMS did not improve, then dantrolene 40mg daily was initiated but risperidone was maintained. | After 11 month after discharge the patient did not experience NMS relapse. |

CDA: clinical dysphagia assessment; DA: dysphagia assessment; ENT: ear, nose and throat examination; FOIS: Function Oral Intake Scale Score; MBS: modified barium swallow; NE: neurological examination; NMS: neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Age range of cases included was 18–89 years, with a mean age of 48±19.48 years.

Antipsychotic-related dysphagia was reported in patients with psychiatric disorders (9 in patients with schizophrenia,31,35,37,39,45,48,52,54,56 4 in patients with bipolar disorder41,44,50,55 4 in patients with depression,24,25,28,30 3 in patients with psychosis,23,44,51 2 in patients with schizoaffective disorder,36,49 2 in patients with behavioral disorder26,42 and 1 in a patient with delirium),42 in patients with dementia (2 in patients with Alzheimer disease33,53 and 3 in other dementia disorders),34,38,53 in 2 patients with insomnia,22,27 in 1 patient with Huntington's disease47 and in 1 with severe mental retardation.46

Antipsychotic drugs related to dysphagiaWe found 14 cases of OD related to typical antipsychotics and 22 related to atypical.

Among typical antipsychotics, in 6 of the cases OD was considered related with haloperidol,25,27–29,31,32 2 with flupenthixol,22,35 2 with trifluoperazine,24,30 2 with loxapine,26,33 1 with chlorpromazine,23 1 with fluspirilene34 and 1 with fluphenazin;52 and, among atypical antipsychotics, 9 of the cases of OD were considered related with risperidone38,39,46,48,51–54,56 but also with quetiapine,36,40,41,55 olanzapine,37,43,50 aripiprazole,42,43 ziprasidone (two cases),44 paliperidone45 and clozapine.49

Neurological and dysphagia featuresDysphagia occurred together with other parkinsonian features in 14 of the cases24,28–31,34,35,37,40,41,44,47,53,56 while it was the only prominent manifestation of EPS in other 14 13,23,25–27,32,36,39,42,45,50–52,54 The onset of symptoms after initiation of antipsychotic drug was variable and ranged from a few days to three months, with the majority of patients (65%) complaining of disturbed swallowing within the first month.

As in patients with Parkinson's disease, EPS-related dysphagia affected all stages of swallowing. Thus, in the majority of patients reported so far, oral dysfunction and pharyngeal dysfunction were observed, and aspiration, the most dangerous consequence of dysphagia, was reported in 8 of the cases.24,25,28,33,35,41,51,52

Dysphagia assessment methodIn eight of the cases included, the authors assessed OD by means of clinical bedside assessment,22,23,27,33,35,42,45,56 in thirteen other cases instrumental assessment was used to assess dysphagia,25,26,28,30,32,35,37,41,44,49,51–53 in six cases both clinical bedside and instrumental assessment were used,23,24,33,35,39,55 in three cases patients by self-reporting swallowing symptoms,48,54,56 and the other twelve case reports did not specify the method of dysphagia assessment.

TreatmentSeveral strategies to resolve dysphagia were reported: changing to another antipsychotic,23,26,32,33,36,39,42,43,45,46,53,55 changing to a nonantipsychotic drug,37,41,50,60 discontinuing antipsychotic therapy or lowering the dose,25,28,30,31,38,41,47,51,52,54 continuing with the same treatment after administering a drug that reversed the effect,22,27,34,35,44,49,56 stopping the treatment and administering a drug that reversed the effect,29,40,44,48 and swallowing training.24

Clinical outcomeAll patients resolved dysphagia after the treatment (within 5min, in the cases where a drug was used to resolve the symptoms, to 11 months).

The characteristics of the clinical cases reported in the literature of patients with dysphagia following antipsychotics regarding the type of antipsychotic are summarized in Table 4.

Summarize of the characteristics of the clinical cases reported in patients with dysphagia following antipsychotics.

| Typical antipsychotics | Atypical antipsychotics | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of clinical cases reported (%) | 14 (38.8%) | 22 (61.1%) |

| Age and sex of the patients | 58.1±21.0 years | 43.0±17.1 years |

| 50% man | 68.2% man | |

| Other manifestations of EPS (yes/no) | ||

| Yes | 9 (64.3%) | 5 (22.7%) |

| No | 4 (28.6%) | 10 (45.4%) |

| Not provided | 1 (7.1%) | 7 (31.8%) |

| Dysphagia assessment method (N, %) | ||

| Clinical bedside assessment Instrumental assessment | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| 5 (35.7%) | 8 (36.4%) | |

| Bedside and instrumental assessment | 4 (28.6%) | 2 (9.1%) |

| Self-reporting swallowing symptoms | 3 (21.4%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| Not specified | 0 (0%) | 8 (36.4%) |

| Treatment strategy (N, %) | ||

| Change to another antipsychotic | 4 (28.6%) | 8 (36.4%) |

| Change to a nonantipsychotic drug | 2 (14.3%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| Dose reduction | 4 (28.6%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| Administering a drug that reversed the effect | 5 (35.7%) | 6 (27.3%) |

| Swallowing training | 1 (7.1%) | 0 (0%) |

EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms.

Antipsychotic-associated dysphagia is a clinically relevant issue, as consistently documented in several case reports in patients of all ages. This systematic review offers an overview of the various case reports dealing with antipsychotic drugs and their impact on swallowing function. The first conclusion we can draw is that the level of evidence on the effect of antipsychotic medication on the swallowing function is scarce as most of the information comes from case reports, but it is frequently reported.

Older patients are at increased risk for extrapyramidal adverse effects of these medications.57 It is worth noting that the demographic characteristics of the cases included in this study suggested that antipsychotic-related dysphagia, although more common in older people, may occur in patients of all ages, and generally in dementia people and those institutionalized in mental health services.

We found 14 cases of dysphagia related to typical antipsychotics and 22 cases of dysphagia related to atypical antipsychotics. Even though this difference could be attributed to a publication bias, we have to emphasize again the capacity of atypical antipsychotics to be associated with OD, an issue sometimes neglected by clinicians. Dopaminergic neurons are felt to play a role in the homeostasis of the extrapyramidal system, which is thought to modulate and regulate motor neurons resulting in coordination of complex muscle movements such as swallowing.58 In half the cases, dysphagia occurred together with other parkinsonian features but in the other half, OD was present as an isolated symptom. From a clinical point of view, isolated symptom cases present a difficult challenge as the relationship between OD and antipsychotics may go unnoticed.

Antipsychotic-associated swallowing disorders have been commonly attributed to the blockage of dopamine D2 receptors in the nigrostriatal pathway, causing EPS and tardive dyskinesia. Antipsychotic-related dysphagia has been reported to affect both the oral and the pharyngeal stages of swallowing due to the complex neuromodulatory control of coordinated movement in these phases.57

There is not a definitive and unique solution for antipsychotic related dysphagia and various actions were taken to resolve the swallowing affectation of the cases reported: changing to another antipsychotic, discontinuing antipsychotic therapy, lowering the dose, administering a drug that reversed the effect or performing swallowing therapy. While the swallowing problems was resolved positively in all cases, indicating the reversible effect of antipsychotic-related dysphagia, when changing to other antipsychotics it is important to remember that atypical antipsychotics may also affect swallowing function.

Our systematic review has several strengths; we conducted extensive literature searches, did not impose restrictions according to time of publication, assessed the reported cases according to predefined criteria and tried to exclude bias where we could. We were able to include more case reports than any previous review has done. However, our systematic review also has a number of important limitations, which pertain to the potential incompleteness of the evidence. Antipsychotics related OD is likely to be underreported; therefore, the number of cases summarized here is less meaningful than the fact that such incidents exist at all. Moreover, a systematic review does not allow to draw conclusions about the theorical more incidence of dysphagia following typical in comparison with atypical antipsychotics, since dysphagia related to atypical antipsychotics may be more reported than with typical antipsychotics. The often-low quality of the primary reports further limits the conclusiveness of our findings. Several reports lacked sufficient detail, which renders the interpretation of their findings problematic. Given such limitations, a cause-effect relationship between the antipsychotics and OD is frequently difficult to establish. We did not include systematic reviews, clinical trials, surveys and cohort studies in our review. A previous systematic review of our team consisting of randomized clinical trials and observational studies also concluded that OD could be considered as an adverse effect of antipsychotic medication.59

In conclusion, several case reports of adverse effects regarding both typical and atypical antipsychotics have been published and some of them had serious consequences, even being reversible. Clinicians should be aware of this potential highlighting risk associated with antipsychotics.

Authorship statementGuarantor of article: Marta Miarons.

Specific author contributions: MM and LR: designed, coordinated the study, performed the research and drafted the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial supportNone of the authors have any conflict of interest nor have received any funding related to the present study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

We thank Jane Lewis for reviewing the English of the manuscript. This work has been conducted within the framework of a doctoral thesis in medicine from the Autonomous University of Barcelona.