Progressively the issues related to the end-of-life process have gained interest in the last decade in our country. From perspectives in various fields, such as political, legal, ethical or medical-legal perspective, a debate and the contribution of new concepts arise. The advances of medicine and other related sciences entail the extension or maintenance of a person's life to limits unsuspected a few years ago. This, together with the aging of the population, assistance to people with advanced chronic diseases and fragile patients, underlines the relevance of this debate.

In recent months, the political debate about dignified death has been significantly intensified in Spain. Although it is not the first time that this debate has reached the Congress of Deputies, several political parties have recently submitted motions to address the end-of-life conditions, including decriminalizing euthanasia in one of these motions.1–3

In this paper we intend to present comprehensive and coordinated ethical, medical and legal aspects in this respect, so that health professionals have the necessary updating to act according to the lex artis, in the current legislation, and to promote reflection in the profession on this matter, in anticipation of potential future changes in regulation.

Ethical issuesThe end-of-life process is a particularly complex field in technologically developed societies. The management of this process generates ethical dilemmas that require a careful and respectful look to the person's dignity.4–7 There are usually situations of great technological complexity and very emotional that require the discernment of entities of interdisciplinary deliberation, such as health care ethics committees.

It is a duty of the ethics of health professionals, doctors, nurses and the whole technical body, to accompany the patient to die with dignity, to scrupulously respect their decisions and to alleviate all manifestations of pain and suffering.

To seek a peaceful death taking into account the system of values and beliefs of the patient constitutes an ethical imperative. However, this professional duty opens a range of interpretations and practices based on the contexts, the actors involved and the beliefs and values of the professional, the patient and their family. The expression “to accompany to die with dignity” is a desideratum that shelters practices and decisions of very different nature and, sometimes, legitimizes actions located on opposite sides.8–11

We are not intending to enter into the casuistic analysis, which is part of a healthcare ethics committee. We propose to briefly outline some aspects of an ethical nature that, necessarily, must be taken into account when elucidating this final process in order to guarantee, at all times, respect for the inherent dignity of the patient and, in turn, ensure maximum quality and maximum well-being during the last phase of their lives.

Information managementIn addition to a legal obligation (Law 41/2002), informing patients in a truthful, intelligible and appropriate way about their diagnosis and prognosis is an ethical and deontological duty.12 The management of information in the process of the end of life entails some extraordinary difficulties due to the emotional impact that certain messages can cause.

Truthfulness is a basic duty of professional ethics and, in turn, is the cornerstone of patient autonomy. Only if the patient knows, in a truthful way, what his diagnosis and prognosis is, he can decide how he wishes the end-of-life process to develop. The right to information is one of the basic rights of the patient. This requires a fluent communication on the part of the professional, avoiding false expectations and providing proper adaptation to the level of understanding of the patient.13 In any case, we should not tell white lies, because, in essence, it constitutes an exercise of medical paternalism. The patient, despite his vulnerability, must be treated, always and in any circumstance, as a valid interlocutor.

The recipient of the information is the patient himself and not his family or his representative. However, sometimes, the patient, because of his vulnerability, is not able to understand or even hear such information. Therefore, the professional must communicate to his family or his representative about the situation so that they may decide consciously, respecting the patient's values and beliefs. This surrogate autonomy does not guarantee, in any case, arbitrariness, since the recipient of such autonomy has the duty to decide considering the beliefs and values of the patient, and put himself in the patient's shoes.

Respect for patient autonomyThe patient, as a subject of rights, is granted the right to decide freely and responsibly in the area involving his body and his life, provided that such decision does not cause damages to third parties. This is known as the principle of autonomy, one of the most underlined principles in the collective imagination. To this purpose, he should be able to understand the range of exiting options and, subsequently, be able to weigh and assess the consequences of each one of them.

In certain situations, the patient lacks the ethical competence to make such decisions given their delicacy. In such a case, it is necessary to inquire whether there is any previous recorded manifestation of their decision in any advance healthcare directive (AHD) or living will. As the data show, a large majority of people facing their end-of-life lack such a document,14 which, in a situation of ethical incompetence, autonomy to decide is surrogated to their family or legal representative.

This task is not easy. In certain situations there is no consensus among the family members and we can find very antagonistic opinions. Health professionals ought to adequately inform and help mediate and deliberate with the family about the best option, without violating their autonomy and always respecting their discernment process.

Caring about privacyThe right to privacy is one of the fundamental rights of the patient. Health professionals should be particularly respectful about this right in the end-of-life process.

The patient who fully assumes the end of his life, because he has been properly informed, has the right to share in privacy his farewell with his loved ones and must be able to communicate with the people he deems appropriate. This means that he must be provided with suitable spaces for it, with privacy.

The right to equityRespect for equity is a basic ethical principle in The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.15 The government must ensure that every citizen, regardless of his resources, origin and any trait of his nature, be treated with dignity and respect during their end-of-life process.

Respect for equity should not mean, in any case, a poorer assistance or equal treatment, since each human being constitutes a unique and unrepeatable entity, endowed with a biography and particular circumstances. Therefore, the assistance should be personalized, fulfilling with the needs of every human being in the final phase.

The limitation of therapeutic effortThe limitation of the therapeutic effort constitutes an ethical figure accepted by the majority of the European specialists in bioethics and in biorights. Faced with the therapeutic obstinacy and the danger of dysthanasia, it is crucial to claim the limitation of the therapeutic effort, taking into account the patient's will, diagnosis and prognosis, and simultaneously, the suffering that a medical intervention might cause to him.

The principle of nonmaleficence requires at all times to safeguard against harm. This means the willingness to mitigate and alleviate suffering, even if such a commitment results in hastening the dying process. The patient can decide how he wants his final stretch of life to be managed. If medically indicated, the patient can opt for palliative sedation, assuming the consequences that it entails. The perspective of the family should be respectful to the patient's will and, under no circumstances, should the patient be subject to coercion or emotional coercion.

Calming down emotions during the processFinally, a last issue particularly relevant in the comprehensive care of the person in the end-of-life process has to do with his emotional and spiritual care. Both health professionals and family members should actively collaborate to make this process emotionally peaceful, facilitating the farewell ritual and reconciliation processes necessary for the patient to die in peace and release his thoughts and emotions. This assistance should include spiritual needs and, in addition, if the patient wishes, the support and accompaniment from his corresponding religion.

The patient must be assisted and accompanied in his end-of-life process by the symbolic and ritual elements proper to his spiritual and religious tradition, as long as it does not cause any prejudice to third parties.16 The right to freedom of thought and belief must be specially considered in the end-of-life process. Therefore, health care centers, regardless of their mission and corporate values, must ensure that this assistance is provided, within the freedom and respect for axiological and spiritual plurality.17,18

Medical and legal issuesOur legislation includes the right to receive comprehensive and quality care and the right to the patient autonomy be respected, also in the end-of-life process. The medical paradigm of patient autonomy has profoundly modified the values of the clinical relationship and must be adapted to the concrete circumstances of the individual.19

The so-called Oviedo Convention,20 signed on 4 April 1997, stipulates in Article 5 that, in order to be able to carry out an intervention in the field of healthcare, it is essential that the persons concerned give their consent previously, freely and without any doubt. Individual autonomy is also recognized in Article 5 of the Universal Declaration on Bioethics and Human Rights, adopted on 19 October 2005 by the General Conference of Unesco.21

Law 41/2002, regulating patient autonomy and the rights and obligations in the field of information and clinical documentation,19 developed by the aforementioned Oviedo Convention20 in Spain, adequately reflects these issues. Every person or patient has the right to receive truthful information about their process and disease, to refuse treatment, to limit therapeutic effort and to choose among the available options. The principle of patient autonomy in the dying process can be articulated through appropriate informed decision making at that time or through an AHC. Various regional regulations22 have allowed its development and implementation, but it is necessary to continue advancing and improve in the advance planning of healthcare, as well as in the knowledge of the Advance Healthcare Directive Registry and its documents and accessibility, both by the citizens and by the professionals assisting them.14

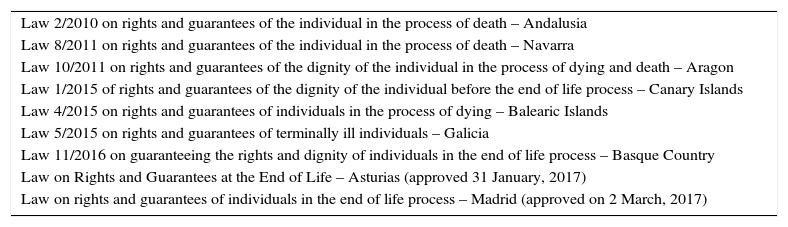

In general, the state legislation can be considered insufficient to guarantee the freedom of the person in the end of life process and certain autonomous communities have decided to legislate this issue specifically. Andalusia was a pioneer with Law 2/2010, of rights and guarantees on the dignity of the person in the end-of-life process,23 and 8 communities have followed it up to date (Table 1).24–31

Current legislation on end-of-life process.

| Law 2/2010 on rights and guarantees of the individual in the process of death – Andalusia |

| Law 8/2011 on rights and guarantees of the individual in the process of death – Navarra |

| Law 10/2011 on rights and guarantees of the dignity of the individual in the process of dying and death – Aragon |

| Law 1/2015 of rights and guarantees of the dignity of the individual before the end of life process – Canary Islands |

| Law 4/2015 on rights and guarantees of individuals in the process of dying – Balearic Islands |

| Law 5/2015 on rights and guarantees of terminally ill individuals – Galicia |

| Law 11/2016 on guaranteeing the rights and dignity of individuals in the end of life process – Basque Country |

| Law on Rights and Guarantees at the End of Life – Asturias (approved 31 January, 2017) |

| Law on rights and guarantees of individuals in the end of life process – Madrid (approved on 2 March, 2017) |

In general terms, these autonomic laws extend what has already been provided in the Law of Patient Autonomy, reinforcing it. These laws provide and develop the rights that assist the patient in this situation and the duties of the healthcare personnel during this process, and provide a set of obligations to public or private social and health institutions in order to guarantee them.

They define a series of concepts related to the assistance to the dying process, such as: limitation of therapeutic effort, therapeutic obstinacy, futility of treatment, end-of-life individuals, advance care planning or palliative and terminal sedation, and others. They also specifically include as rights of individuals in the end-of-life process and related duties: the duty to always promote their participation in decision-making; the right to clinical information, the right to refuse it or to inform third parties; the right to informed decision making, either directly or through the granting of an AHC, following a process of communication and conversation and that these are fulfilled; the obligation of oral or written informed consent, in the cases provided by law; the right to refuse interventions and this to be respected; the right to adequate means of care and means of life support, especially in terms of alleviating suffering, alleviating pain or other symptoms and making the end of life process more dignifying and endurable; the consent by representation appropriate to the circumstances and providing the requirements to be attended, indicating who will be appointed as representative according to the circumstances, together with the obligation of the representative to act in the best interest and respect for the dignity and will of the represented person; the right to quality comprehensive palliative care and to choose where to receive them; and the right to privacy and confidentiality. In this regard, we should outline the right in some communities to have a single room and the company of relatives in that moment of maximum privacy. There are also specific references to the special situation of the disabled patients and the assessment of their competence, to patients legally incapacitated and to minors, urging to review the particular judicial decision. Finally, the legislation provides that health centers and institutions should offer guarantees regarding all of the aforementioned, as well as support for families or caregivers and access to those who provide them with spiritual support.

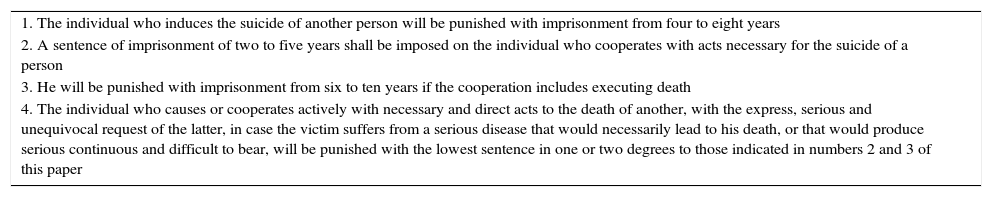

Some of these laws make explicit reference to the difference of regulated procedures on the end of life process with the concept popularly identified as euthanasia. Thus, article 143 of the current Penal Code32 penalizes assisted suicide. The limitation of therapeutic effort against the futility of treatment and the irreversibility of a disease, allowing death by withdrawal or non-initiation of life support, is not penalized. The criminal offenses in this regard, according to the current Penal Code, are shown in Table 2, deserving special mention the expected reduction of the sentence in the cases of article 143.4.

Criminal offenses in relation to suicide (article 143, Criminal Code).

| 1. The individual who induces the suicide of another person will be punished with imprisonment from four to eight years |

| 2. A sentence of imprisonment of two to five years shall be imposed on the individual who cooperates with acts necessary for the suicide of a person |

| 3. He will be punished with imprisonment from six to ten years if the cooperation includes executing death |

| 4. The individual who causes or cooperates actively with necessary and direct acts to the death of another, with the express, serious and unequivocal request of the latter, in case the victim suffers from a serious disease that would necessarily lead to his death, or that would produce serious continuous and difficult to bear, will be punished with the lowest sentence in one or two degrees to those indicated in numbers 2 and 3 of this paper |

Many countries around the world have specific legislation on the end of life process, and some of them have legislated even on euthanasia and have medically assisted suicide. We should highlight the laws of Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Switzerland, Canada and some US states (Eg, Oregon, Washington, and California).

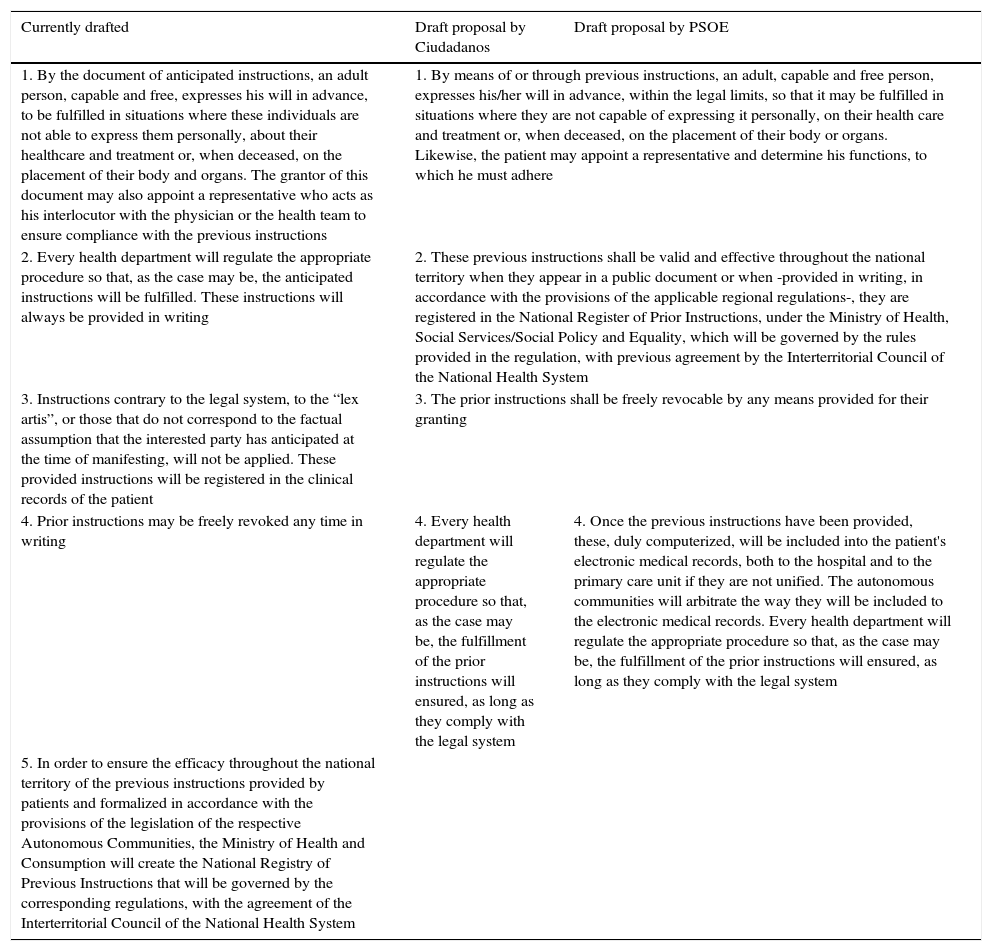

In Spain, there are currently 3 different drafts of Organic Law presented by various parliamentary groups, on the end of life process. The parliamentary group of Ciudadanos has presented the “Draft law of rights and guarantees on the dignity of an individual before the end of life process”, while the Socialist parliamentary group has presented the “Draft law regulating the rights of an individual before the end of life process.” Both Draft laws coincide essentially with what has been regulated in the autonomies, considering palliative sedation in agony and including non-universal nuances such as the obligation of professionals to consult the Advance Directive Registry before an incapacitated patient or the right to a single room and the family support and spiritual support. Most prominently, they include the suppression of point 3 of article 11 of the Law of Patient Autonomy (Table 3), thus omitting mention of the lex artis and, in the case of Ciudadanos, they add the right of professionals to conscientious objection to the legal obligation to respect the patient's will, values, beliefs and preferences in clinical decision-making (Article 15). Both characteristics are controversial and count with the disagreement of the End-of-Life Medical Care Group of the Medical Organization and the Spanish Society of Palliative Care (SECPAL). To obviate lex artis, which is the true guarantee of good medical practice, would mean to modify its foundations based on scientific knowledge, ethical bases and legal regulations.

Amendment proposal of article 11 of the Autonomy Law.

| Currently drafted | Draft proposal by Ciudadanos | Draft proposal by PSOE |

|---|---|---|

| 1. By the document of anticipated instructions, an adult person, capable and free, expresses his will in advance, to be fulfilled in situations where these individuals are not able to express them personally, about their healthcare and treatment or, when deceased, on the placement of their body and organs. The grantor of this document may also appoint a representative who acts as his interlocutor with the physician or the health team to ensure compliance with the previous instructions | 1. By means of or through previous instructions, an adult, capable and free person, expresses his/her will in advance, within the legal limits, so that it may be fulfilled in situations where they are not capable of expressing it personally, on their health care and treatment or, when deceased, on the placement of their body or organs. Likewise, the patient may appoint a representative and determine his functions, to which he must adhere | |

| 2. Every health department will regulate the appropriate procedure so that, as the case may be, the anticipated instructions will be fulfilled. These instructions will always be provided in writing | 2. These previous instructions shall be valid and effective throughout the national territory when they appear in a public document or when -provided in writing, in accordance with the provisions of the applicable regional regulations-, they are registered in the National Register of Prior Instructions, under the Ministry of Health, Social Services/Social Policy and Equality, which will be governed by the rules provided in the regulation, with previous agreement by the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System | |

| 3. Instructions contrary to the legal system, to the “lex artis”, or those that do not correspond to the factual assumption that the interested party has anticipated at the time of manifesting, will not be applied. These provided instructions will be registered in the clinical records of the patient | 3. The prior instructions shall be freely revocable by any means provided for their granting | |

| 4. Prior instructions may be freely revoked any time in writing | 4. Every health department will regulate the appropriate procedure so that, as the case may be, the fulfillment of the prior instructions will ensured, as long as they comply with the legal system | 4. Once the previous instructions have been provided, these, duly computerized, will be included into the patient's electronic medical records, both to the hospital and to the primary care unit if they are not unified. The autonomous communities will arbitrate the way they will be included to the electronic medical records. Every health department will regulate the appropriate procedure so that, as the case may be, the fulfillment of the prior instructions will ensured, as long as they comply with the legal system |

| 5. In order to ensure the efficacy throughout the national territory of the previous instructions provided by patients and formalized in accordance with the provisions of the legislation of the respective Autonomous Communities, the Ministry of Health and Consumption will create the National Registry of Previous Instructions that will be governed by the corresponding regulations, with the agreement of the Interterritorial Council of the National Health System | ||

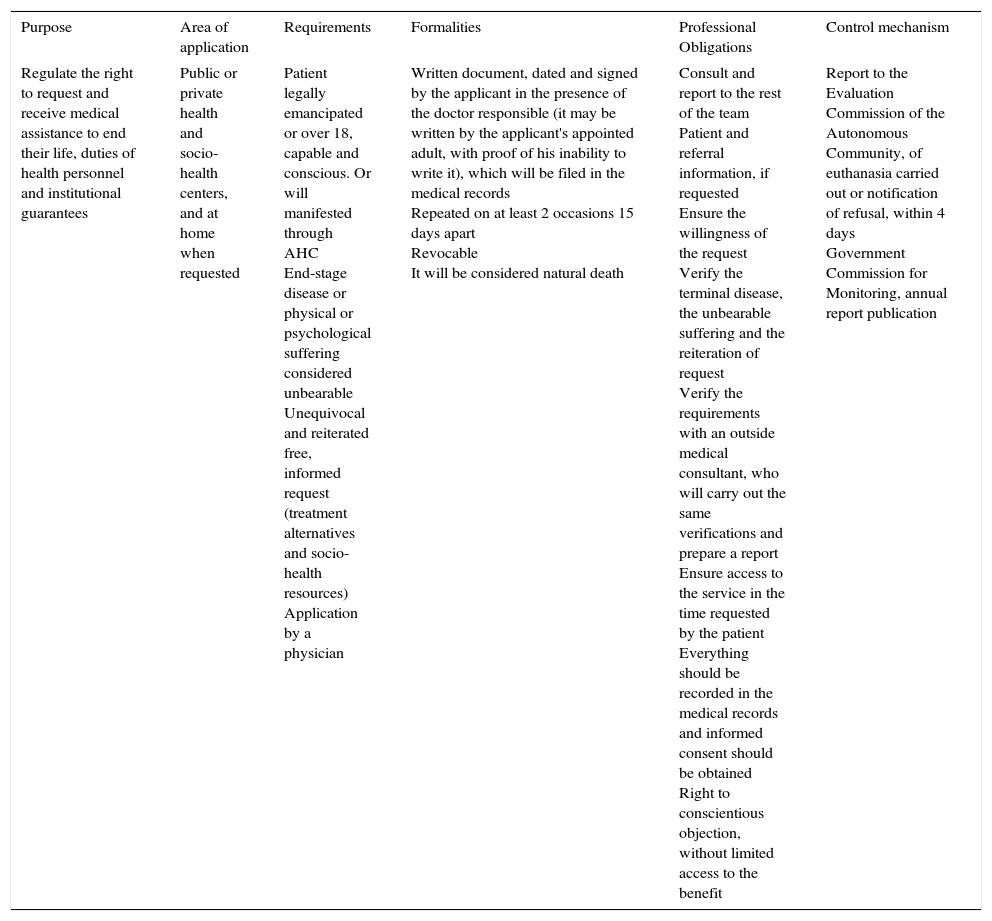

Finally, the Draft Law proposed by the parliamentary group Podemos, which was rejected at the end of March by the Congress of Deputies – 86 deputies in favor, 132 against and 122 abstentions – is the only one that refers directly to euthanasia and includes a Draft Amendment to article 143.4 of the Criminal Code: “The conduct of one who cooperates with necessary and direct acts or causes the death of an individual will not be punishable when this individual has expressly, unequivocally and repeatedly requested it in accordance with what is provided in the specific legislation”. The applicant must be a person with a serious disease that necessarily leads to his death or who suffers physical or mental suffering that he considers unbearable. The concrete characteristics of this Draft are shown in Table 4.

Draft organic law on euthanasia of the parliamentary group Podemos (rejected by Congress in March 2017).

| Purpose | Area of application | Requirements | Formalities | Professional Obligations | Control mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regulate the right to request and receive medical assistance to end their life, duties of health personnel and institutional guarantees | Public or private health and socio-health centers, and at home when requested | Patient legally emancipated or over 18, capable and conscious. Or will manifested through AHC End-stage disease or physical or psychological suffering considered unbearable Unequivocal and reiterated free, informed request (treatment alternatives and socio-health resources) Application by a physician | Written document, dated and signed by the applicant in the presence of the doctor responsible (it may be written by the applicant's appointed adult, with proof of his inability to write it), which will be filed in the medical records Repeated on at least 2 occasions 15 days apart Revocable It will be considered natural death | Consult and report to the rest of the team Patient and referral information, if requested Ensure the willingness of the request Verify the terminal disease, the unbearable suffering and the reiteration of request Verify the requirements with an outside medical consultant, who will carry out the same verifications and prepare a report Ensure access to the service in the time requested by the patient Everything should be recorded in the medical records and informed consent should be obtained Right to conscientious objection, without limited access to the benefit | Report to the Evaluation Commission of the Autonomous Community, of euthanasia carried out or notification of refusal, within 4 days Government Commission for Monitoring, annual report publication |

AHC: advance healthcare directive.

The subject of discussion is not at all simple. The concept of euthanasia can be misleading and responds to subjective interpretations, currently polarizing society. However, it is urgent to establish as a priority and to protocol end-of-life care, guaranteeing the universalization of palliative care to all segments of the population. Comprehensive healthcare should be reinforced in this situation, maximizing well-being levels, which can potentially have a direct influence on decision making. Concepts such as limitation of therapeutic effort, therapeutic futility or proportionality of care must be addressed jointly and empathically by health professionals, patients and relatives, respecting the patient autonomy. From the public institutions and health institutions, pedagogy should be promoted on the tools about decision making, rarely used, hekping their incorporation as a tool of clinical safety to the lex artis, also increasing the legal security of professionals.

The current debate on helping ending life can be demagogic and superficial if it does not take into account all the actors involved in the process. The proposed decriminalization of article 143, i.e. the decriminalization of euthanasia and assisted suicide, should consider the associated risks, such as those resulting from a potential impairment of decision-making competence in situations at the end of life, and the protocols on this issue should be agreed and performed adequately. Generalizations cannot be included and the debate is not considered viable without previous ethical and medical-legal reflection, involving the professionals and patients directly involved.

According to the latest data provided by the SECPAL, in Spain only half of the patients who need specialized palliative care receive it. This means that around 60,000 people die every year with intense, avoidable suffering because they do not receive proper care. An advanced country must have resources to alleviate human suffering, other than ending the life of the suffering. The debate on euthanasia should be based on extensive experience on comprehensive and adequate care for the end of life process that might involve social opinion regarding the need for a potential legislative modification.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arimany-Manso J, Torralba F, Gómez-Sancho M, Gómez-Durán EL. Aspectos éticos, médico-legales y jurídicos del proceso del final de la vida. Med Clin (Barc). 2017;149:217–222.