This study aimed to investigate the role and prognosis of Alzheimer disease biomarkers in patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at a memory clinic in Latin America.

MethodsWe studied 89 patients with MCI, 43 with Alzheimer-type dementia, and 18 healthy controls (matched for age, sex, and educational level) at our memory clinic (Instituto FLENI) in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Patients and controls underwent an extensive demographic, neurological, and neuropsychological assessment. All subjects underwent a brain MRI scan; FDG-PET scan; amyloid PET scan; apolipoprotein E genotyping; and cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of Aβ1-42, tau, and phosphorylated tau. Patients were categorised as positive or negative for the presence of amyloid pathology and neurodegeneration.

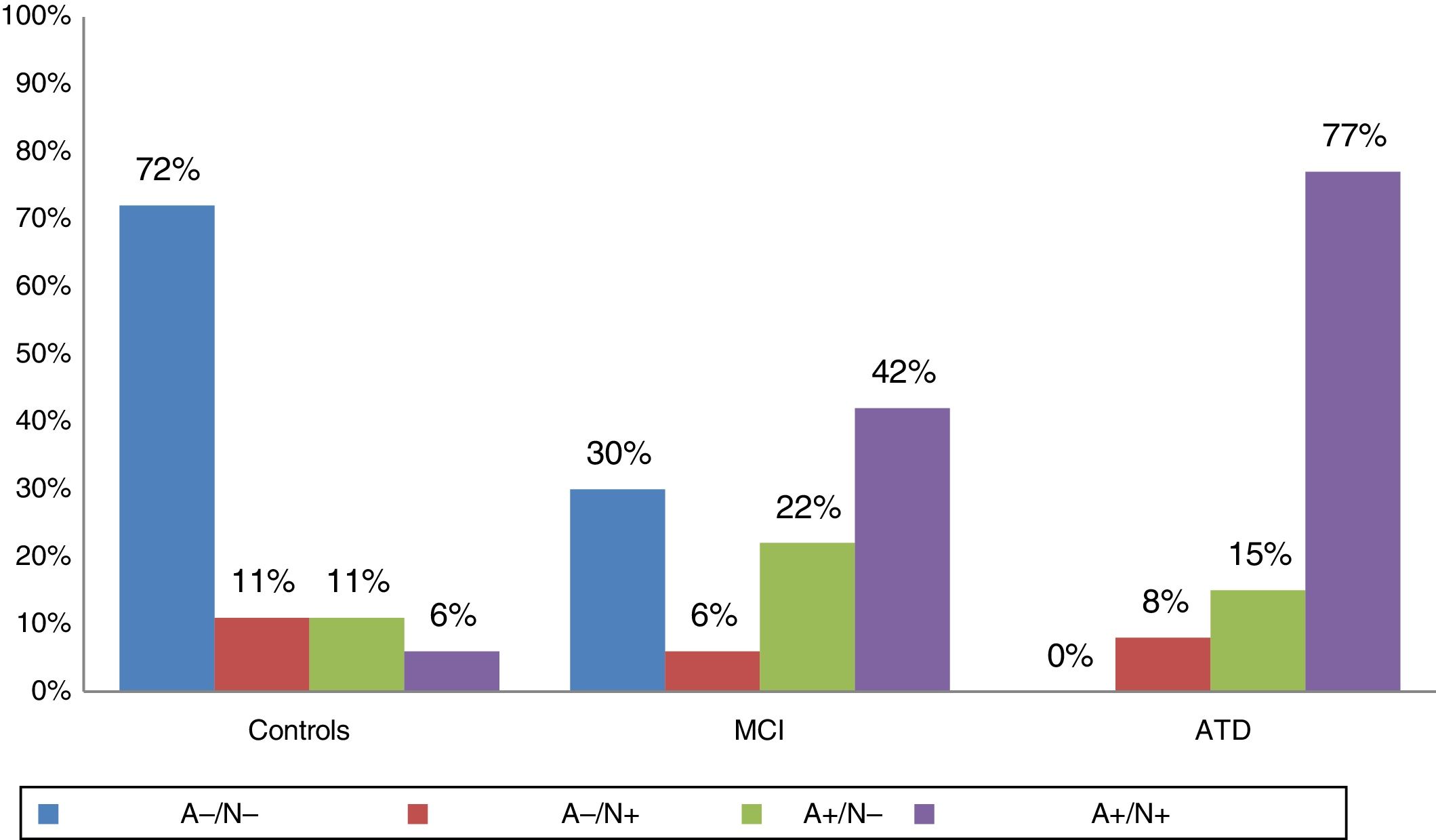

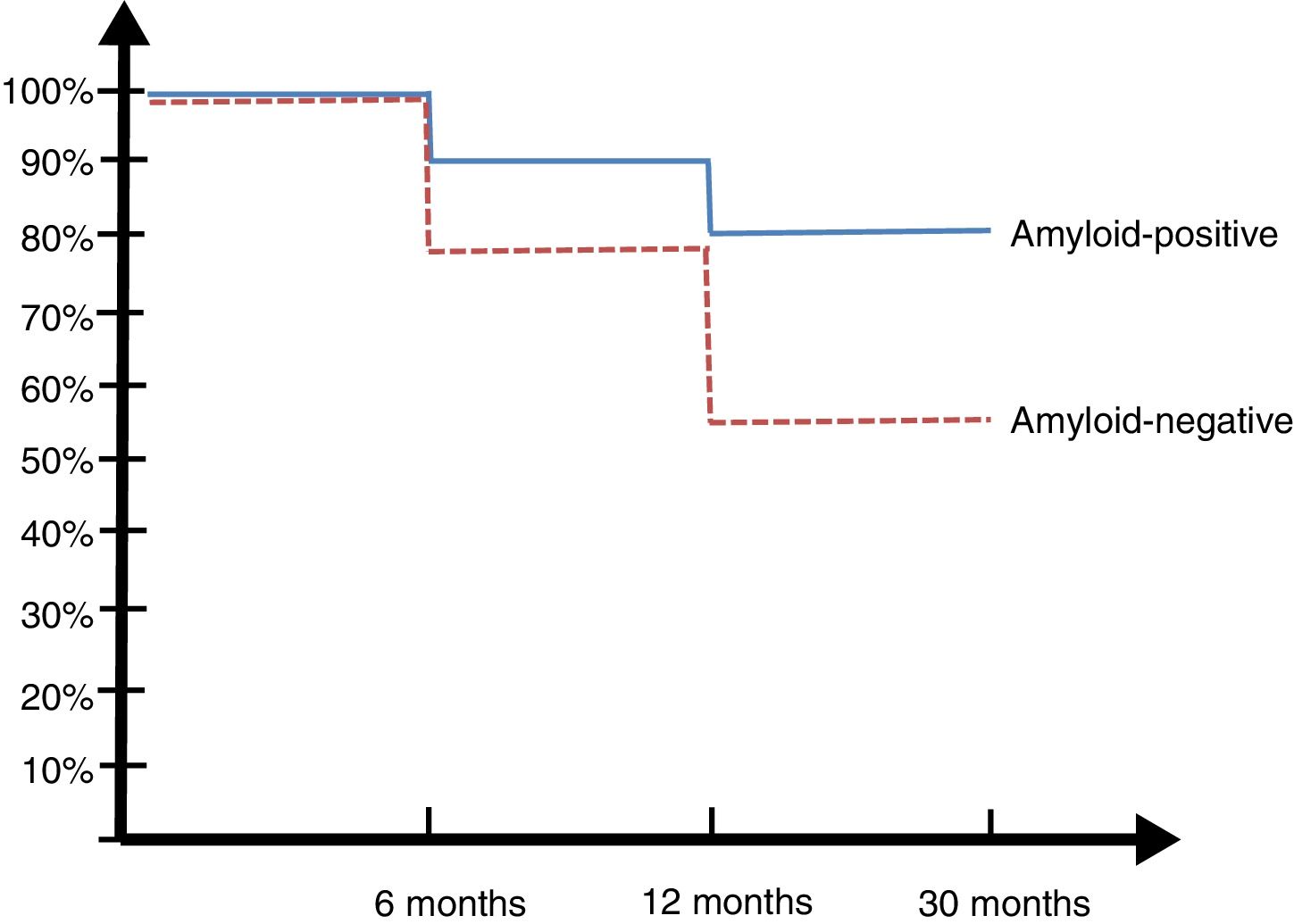

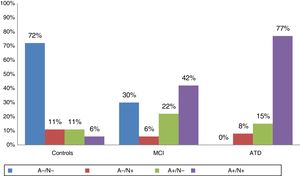

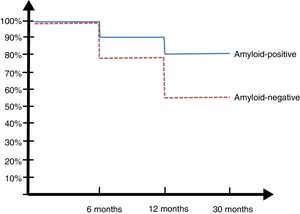

ResultsAmyloid pathology was observed in cerebrospinal fluid results in 18% of controls, 64% of patients with MCI, and 92% of patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Suspected non-Alzheimer disease pathophysiology was found in 11% of controls, 6% of patients with MCI, and 8% of patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. At 30 months of follow-up, 45% of amyloid-positive patients with MCI and 20% of amyloid-negative patients with MCI showed progression to dementia.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates biomarker-based MCI prognosis and supports its role in clinical decision-making in daily practice.

El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar el rol y pronóstico de los biomarcadores de enfermedad de Alzheimer en pacientes con diagnóstico clínico de deterioro cognitivo leve (DCL) en una clínica de memoria de Latinoamérica.

MétodoOchenta y nueve pacientes con DCL, 43 con demencia tipo Alzheimer y 18 controles normales apareados por edad, sexo y escolaridad fueron estudiados con un extenso protocolo demográfico, neurológico y neuropsicológico en la clínica de memoria del Instituto FLENI de Buenos Aires. Todos completaron una RM cerebral, una PET con FDG, una PET con estudios amiloideo (PIB), genotipificación de APOE y estudio de Aβ1-42, tau and f-tau de líquido cefalorraquídeo. Basado en la presencia/ausencia de patología amiloidea y neurodegeneración los pacientes fueron categorizados como A+/A− y N+/N− respectivamente.

ResultadosEn el estudio de líquido cefalorraquídeo el 18% de los controles, el 64% de los DCL y el 92% de las demencia tipo Alzheimer tenían patología amiloidea; y un 11% de los controles, el 6% de los DCL y el 8% de las DTA eran sospechosos de fisiopatología no Alzheimer. En el seguimiento a los 30 meses el 45% de los DCL con amiloide positivo y el 20% de los que presentaron amiloide negativo progresaron a demencia.

ConclusionesEste estudio muestra el pronóstico de los DCL basado en los biomarcadores, y respalda su importancia en la toma de decisiones en la práctica diaria.

Alzheimer disease (AD) is characterised by extracellular amyloid-β and hyperphosphorylated tau aggregation in the context of neurofibrillary degeneration. These neuropathological alterations may be identified directly with an amyloid PET scan of the brain1,2 or indirectly by detecting decreased Aβ1-42 levels and increased total tau and phosphorylated tau levels in the CSF.3 Based on the use of these biomarkers, the National Institute of Aging and the Alzheimer's Association established a series of recommendations for the diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) secondary to AD4 and preclinical AD.5 Among the patients studied, some individuals tested negative for both biomarkers (amyloid-negative [A−] and neurodegeneration-negative [N−]), others tested positive for both biomarkers (A+/N+; Alzheimer-profile), and others either tested positive for amyloid but not for degeneration (A+/N−), or vice versa (A−/N+; suspected non-AD pathophysiology [SNAP]).6 This classification of preclinical AD is based on both biomarkers and cognitive criteria: stage 1 is characterised by asymptomatic cerebral amyloidosis (A+/N−), stage 2 involves amyloidosis plus neurodegeneration (A+/N+), and stage 3 includes amyloidosis, neurodegeneration, and subtle cognitive alterations (A+/N+/c+).5

Patients with MCI have classically been considered to present a high risk of dementia; amyloid deposition is attributed to AD, whereas lack of amyloid deposition is considered to indicate a non-Alzheimer neurodegenerative process.

The purpose of this study was to describe the results of a study of AD biomarkers in patients with MCI from a memory clinic in Latin America, and to analyse the involvement of these markers in disease progression in an Argentinian cohort from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI).

Patients and methodsOur analysis included 150 patients from the memory clinic at Instituto de Investigaciones Neurológicas Dr. Raúl Carrea (FLENI), in Buenos Aires, Argentina: 40 patients were gathered from the Argentinian ADNI cohort and 110 from the FLENI database. The sample included 89 patients with MCI, 43 with Alzheimer-type dementia (ATD), and 18 age-, sex-, and education-matched healthy controls. All participants were assessed by an experienced cognitive neurologist (PCM, MJR, JC, or RFA) at the FLENI memory clinic. The initial assessment included a structured interview with patients and relatives, laboratory analyses, and structural and molecular neuroimaging tests. We followed a standardised diagnostic procedure described elsewhere.1 Team members reviewed the results and established a diagnosis for each patient by consensus. MCI was diagnosed according to the criteria established by Petersen and Morris7 and ATD was diagnosed according to the criteria put forward by McKhann et al.8,9 and the DSM-IV criteria for dementia.10 Using the latter set of criteria, dementia may be classified as “clinically probable AD.”

Our study was approved by FLENI's ethics committee and complies with the Argentinian good clinical practice guidelines and the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants and/or their legal representatives gave informed consent.

Follow-up periodWe conducted a supplementary analysis of the Argentinian ADNI cohort (n=40); patients with MCI were followed up during the study period and evaluated at 6, 12, and 30 months. We conducted a survival analysis with a dichotomous outcome variable (transition from MCI to dementia during follow-up); the time of analysis was 30 months (follow-up period).

Neuropsychological test batteryPatients were evaluated with the Mini−Mental State Examination (MMSE),11 the Wechsler Memory Scale,12 the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT),13 the Boston Naming Test,14 phonological and semantic verbal fluency tasks,15 the Trail Making Test,16 the Clinical Dementia Rating scale,17 the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI),18 the Geriatric Depression Scale,19 and the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ).20

Brain MRI findingsAll participants underwent brain MRI studies in a 3T scanner (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, FLAIR, gradient-echo, and diffusion-weighted sequences). Images were stored using the Kodak Carestream system. Hippocampal reconstruction and volumetric segmentation was performed with the Freesurfer image analysis suite, version 4.3 (http://surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu/).

APOE genotypingAll participants underwent APOE genotyping, as in the ADNI studies.1 Patients carrying at least one ɛ4 allele were considered positive carriers.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkersCSF samples were collected by lumbar puncture at L3-L4 to L4-L5, in accordance with the ADNI standards. Samples were collected in polypropylene tubes and stored at −80–°C. Biomarkers were measured at the FLENI molecular biology laboratory using Innogenetics ELISA kits. This laboratory is accredited by the ADNI quality control programme.1 Patients were categorised as positive or negative for amyloidosis (A+ or A−) and neurodegeneration (N+ or N−).

Statistical analysis of dataData were analysed with the SPSS statistical software, version 19.0 (SPSS Inc., IL, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as means (standard deviation [SD]) and categorical variables as frequencies (%). The chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for normal distribution. Homogeneity of variance was evaluated using the Levene test. Continuous variables were compared with ANOVA when the sample followed a normal distribution, or with the Kruskal-Wallis test for non-normally distributed data. We used the Bonferroni post hoc test, and calculated the conversion rate. P-values below .05 were regarded as statistically significant.

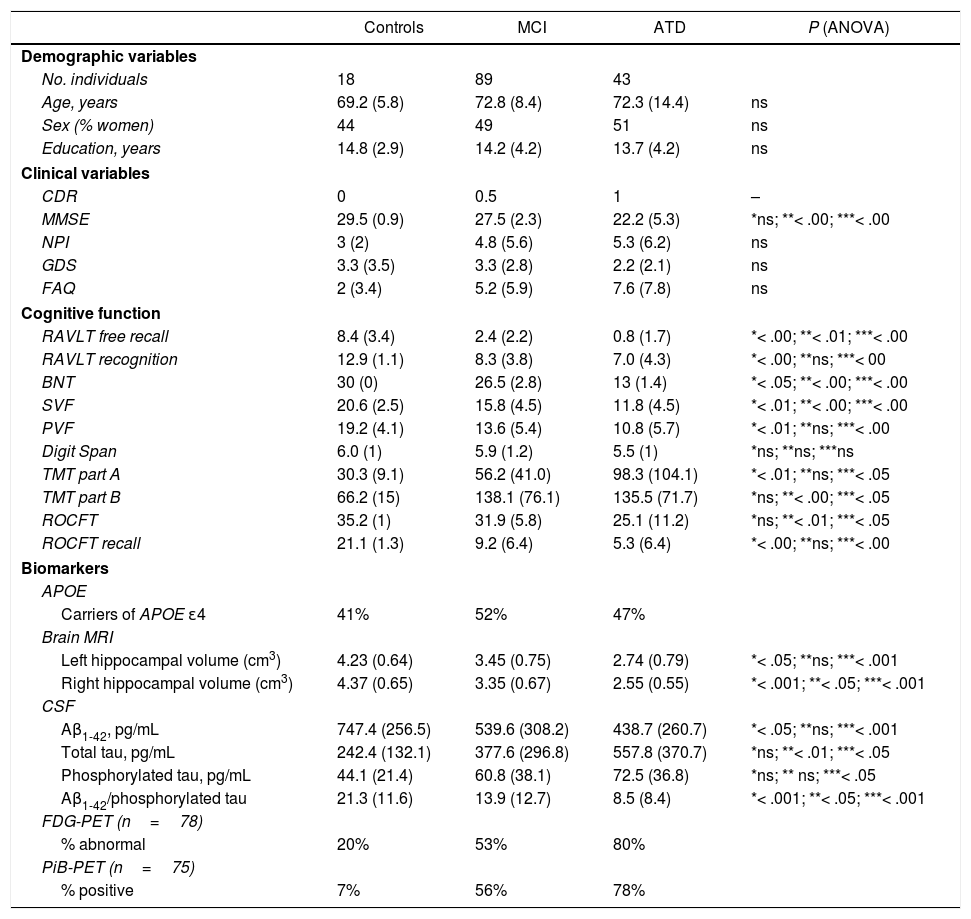

ResultsBaseline characteristics of the participantsBaseline demographic, clinical, cognitive, and biomarker data are summarised in Table 1.

Data on demographic and clinical variables, cognitive function, and CSF biomarkers in our sample.

| Controls | MCI | ATD | P (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | ||||

| No. individuals | 18 | 89 | 43 | |

| Age, years | 69.2 (5.8) | 72.8 (8.4) | 72.3 (14.4) | ns |

| Sex (% women) | 44 | 49 | 51 | ns |

| Education, years | 14.8 (2.9) | 14.2 (4.2) | 13.7 (4.2) | ns |

| Clinical variables | ||||

| CDR | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | – |

| MMSE | 29.5 (0.9) | 27.5 (2.3) | 22.2 (5.3) | *ns; **< .00; ***< .00 |

| NPI | 3 (2) | 4.8 (5.6) | 5.3 (6.2) | ns |

| GDS | 3.3 (3.5) | 3.3 (2.8) | 2.2 (2.1) | ns |

| FAQ | 2 (3.4) | 5.2 (5.9) | 7.6 (7.8) | ns |

| Cognitive function | ||||

| RAVLT free recall | 8.4 (3.4) | 2.4 (2.2) | 0.8 (1.7) | *< .00; **< .01; ***< .00 |

| RAVLT recognition | 12.9 (1.1) | 8.3 (3.8) | 7.0 (4.3) | *< .00; **ns; ***< 00 |

| BNT | 30 (0) | 26.5 (2.8) | 13 (1.4) | *< .05; **< .00; ***< .00 |

| SVF | 20.6 (2.5) | 15.8 (4.5) | 11.8 (4.5) | *< .01; **< .00; ***< .00 |

| PVF | 19.2 (4.1) | 13.6 (5.4) | 10.8 (5.7) | *< .01; **ns; ***< .00 |

| Digit Span | 6.0 (1) | 5.9 (1.2) | 5.5 (1) | *ns; **ns; ***ns |

| TMT part A | 30.3 (9.1) | 56.2 (41.0) | 98.3 (104.1) | *< .01; **ns; ***< .05 |

| TMT part B | 66.2 (15) | 138.1 (76.1) | 135.5 (71.7) | *ns; **< .00; ***< .05 |

| ROCFT | 35.2 (1) | 31.9 (5.8) | 25.1 (11.2) | *ns; **< .01; ***< .05 |

| ROCFT recall | 21.1 (1.3) | 9.2 (6.4) | 5.3 (6.4) | *< .00; **ns; ***< .00 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| APOE | ||||

| Carriers of APOE ɛ4 | 41% | 52% | 47% | |

| Brain MRI | ||||

| Left hippocampal volume (cm3) | 4.23 (0.64) | 3.45 (0.75) | 2.74 (0.79) | *< .05; **ns; ***< .001 |

| Right hippocampal volume (cm3) | 4.37 (0.65) | 3.35 (0.67) | 2.55 (0.55) | *< .001; **< .05; ***< .001 |

| CSF | ||||

| Aβ1-42, pg/mL | 747.4 (256.5) | 539.6 (308.2) | 438.7 (260.7) | *< .05; **ns; ***< .001 |

| Total tau, pg/mL | 242.4 (132.1) | 377.6 (296.8) | 557.8 (370.7) | *ns; **< .01; ***< .05 |

| Phosphorylated tau, pg/mL | 44.1 (21.4) | 60.8 (38.1) | 72.5 (36.8) | *ns; ** ns; ***< .05 |

| Aβ1-42/phosphorylated tau | 21.3 (11.6) | 13.9 (12.7) | 8.5 (8.4) | *< .001; **< .05; ***< .001 |

| FDG-PET (n=78) | ||||

| % abnormal | 20% | 53% | 80% | |

| PiB-PET (n=75) | ||||

| % positive | 7% | 56% | 78% | |

ATD: Alzheimer-type dementia; BNT: Boston Naming Test; CDR: Clinical Dementia Rating scale; FAQ: Functional Activities Questionnaire; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; MCI: mild cognitive impairment; MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; ns: not significant; PVF: phonological verbal fluency (letter “p”); RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; ROCFT: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; SVF: semantic verbal fluency (animals); TMT: Trail Making Test.

Data are expressed as means (standard deviation), unless indicated otherwise. P (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc test.

The 3 groups (MCI, ATD, and controls) were matched for age, sex, and education. All participants were white and were native Spanish speakers. Baseline cognitive assessment scores, hippocampal volume, and CSF biomarker values were significantly different in controls. All 3 groups showed a similar percentage of APOE ɛ4 carriers. Hypometabolism was observed on FDG-PET images in 80% of patients with ATD, 53% of patients with MCI, and 20% of controls. The PiB-PET scan showed positive results in 78% of patients with ATD, 56% of patients with MCI, and 7% of controls.

According to the results of the study of CSF biomarkers, individuals were categorised as A−/N−, A+/N−, A−/N+, or A+/N+. Fig. 1 shows the distribution of biomarkers in each group; 92% of patients with ATD, 64% of patients with MCI, and 18% of controls were amyloid-positive. SNAP was recorded in 11% of controls, 8% of patients with ATD, and 6% of patients with MCI.

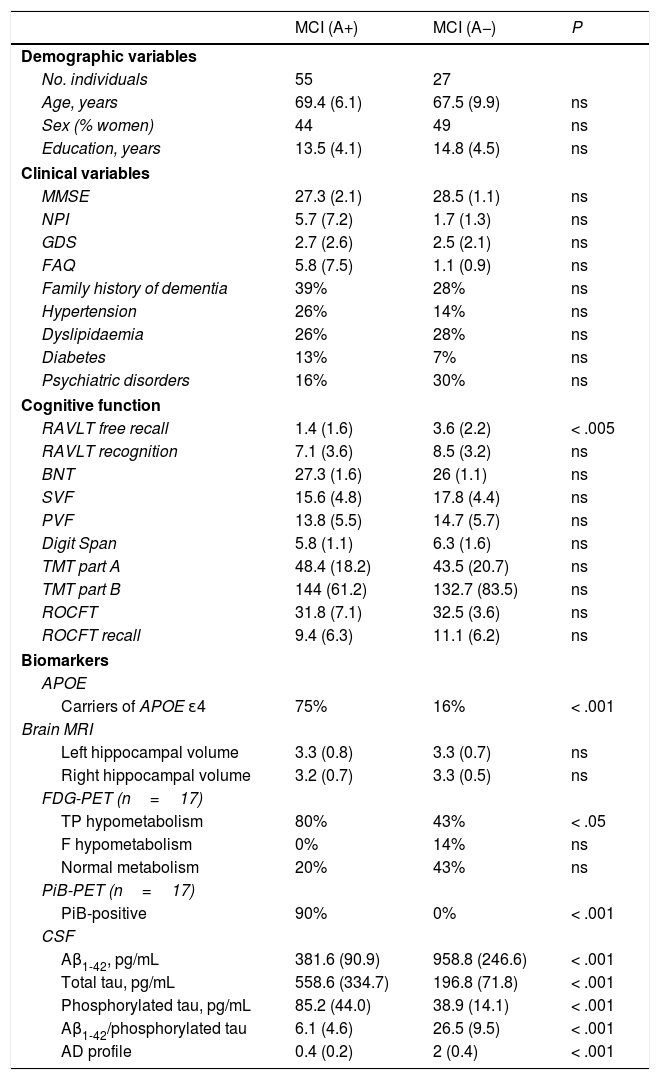

Patients with MCI were classified as either A+ (n=55) or A− (n=27). Both groups were age-, sex-, and education-matched, and showed no differences in global cognitive function (MMSE), neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI), or functional ability (FAQ) (Table 2).

Comparison between patients with mild cognitive impairment with and without amyloidosis.

| MCI (A+) | MCI (A−) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic variables | |||

| No. individuals | 55 | 27 | |

| Age, years | 69.4 (6.1) | 67.5 (9.9) | ns |

| Sex (% women) | 44 | 49 | ns |

| Education, years | 13.5 (4.1) | 14.8 (4.5) | ns |

| Clinical variables | |||

| MMSE | 27.3 (2.1) | 28.5 (1.1) | ns |

| NPI | 5.7 (7.2) | 1.7 (1.3) | ns |

| GDS | 2.7 (2.6) | 2.5 (2.1) | ns |

| FAQ | 5.8 (7.5) | 1.1 (0.9) | ns |

| Family history of dementia | 39% | 28% | ns |

| Hypertension | 26% | 14% | ns |

| Dyslipidaemia | 26% | 28% | ns |

| Diabetes | 13% | 7% | ns |

| Psychiatric disorders | 16% | 30% | ns |

| Cognitive function | |||

| RAVLT free recall | 1.4 (1.6) | 3.6 (2.2) | < .005 |

| RAVLT recognition | 7.1 (3.6) | 8.5 (3.2) | ns |

| BNT | 27.3 (1.6) | 26 (1.1) | ns |

| SVF | 15.6 (4.8) | 17.8 (4.4) | ns |

| PVF | 13.8 (5.5) | 14.7 (5.7) | ns |

| Digit Span | 5.8 (1.1) | 6.3 (1.6) | ns |

| TMT part A | 48.4 (18.2) | 43.5 (20.7) | ns |

| TMT part B | 144 (61.2) | 132.7 (83.5) | ns |

| ROCFT | 31.8 (7.1) | 32.5 (3.6) | ns |

| ROCFT recall | 9.4 (6.3) | 11.1 (6.2) | ns |

| Biomarkers | |||

| APOE | |||

| Carriers of APOE ɛ4 | 75% | 16% | < .001 |

| Brain MRI | |||

| Left hippocampal volume | 3.3 (0.8) | 3.3 (0.7) | ns |

| Right hippocampal volume | 3.2 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.5) | ns |

| FDG-PET (n=17) | |||

| TP hypometabolism | 80% | 43% | < .05 |

| F hypometabolism | 0% | 14% | ns |

| Normal metabolism | 20% | 43% | ns |

| PiB-PET (n=17) | |||

| PiB-positive | 90% | 0% | < .001 |

| CSF | |||

| Aβ1-42, pg/mL | 381.6 (90.9) | 958.8 (246.6) | < .001 |

| Total tau, pg/mL | 558.6 (334.7) | 196.8 (71.8) | < .001 |

| Phosphorylated tau, pg/mL | 85.2 (44.0) | 38.9 (14.1) | < .001 |

| Aβ1-42/phosphorylated tau | 6.1 (4.6) | 26.5 (9.5) | < .001 |

| AD profile | 0.4 (0.2) | 2 (0.4) | < .001 |

BNT: Boston Naming Test; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; F: frontal; FAQ: Functional Activities Questionnaire; GDS: Geriatric Depression Scale; MCI (A+): patients with mild cognitive impairment and amyloidosis; MCI (A−): patients with mild cognitive impairment and no amyloidosis; MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; NPI: Neuropsychiatric Inventory; ns: not significant; PVF: phonological verbal fluency (letter “p”); RAVLT: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test; ROCFT: Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; SVF: semantic verbal fluency (animals); TMT: Trail Making Test; TP: temporoparietal.

Data are expressed as means (standard deviation), unless indicated otherwise. P (ANOVA) and Bonferroni post hoc test.

No differences were observed in any cognitive domain, except for delayed recall (RAVLT free recall; p<.005), or in hippocampal volume. Seventy-five percent of A+ patients with MCI had at least one APOE ɛ4 allele, compared to 16% of A− patients with MCI. Significantly more patients with amyloidosis showed temporoparietal hypometabolism, typical of AD, on FDG-PET images (80%, vs 43% in patients without amyloidosis). Ninety percent of patients with amyloidosis were also PiB-positive.

30-month follow-upPatients from the Argentinian ADNI cohort were evaluated at 6, 12, and 30 months (Fig. 2).

Only one of the 14 controls (7%) developed MCI at 2 years. Eight of the 23 patients with MCI (34.7%) developed ATD: 6 of the 13 A+ patients (45%) and 2 of the 10 A− patients (20%) (SNAP).

DiscussionAD has traditionally been diagnosed according to the 1984 criteria established by McKhann et al.8 However, the emergence of CSF biomarkers of the disease has changed this.21 Petersen and Morris7 attempted to define criteria for early diagnosis of AD, and defined the criteria for MCI as a construct of increased risk. However, the wide range of disorders and prognoses led to confusion in the literature.21,22 The National Institute of Aging and the Alzheimer's Association made new recommendations for diagnosing MCI due to AD, based on AD biomarkers.4 It is widely accepted that novel treatments under development will be particularly beneficial for patients with mild (MCI) or preclinical forms of the disease.23 Thus, biomarkers significantly improve diagnostic accuracy and allow close monitoring of treatment.24 Our study, conducted at a memory clinic in Latin America, explores the clinical applicability of AD biomarkers in our setting. The 3 patient profiles (controls, MCI, and ATD) effectively reflect this population and are easily differentiated based on the neuropsychological characteristics of the classic cortical profile of AD, with more marked involvement in ATD despite the lack of significant differences in MMSE scores between patients with MCI and controls.1,21 Hippocampal volumetry shows progression of bilateral atrophy in patients with MCI, and particularly in those with ATD, as has been reported consistently in the literature.25 CSF Aβ1-42 levels were similar in patients with MCI and in those with ATD, although significant differences were observed between controls and the 2 patient groups. These findings have previously been reported by Sperling et al.,5 who observed a dramatic drop in CSF Aβ1-42 levels in the early stages, which subsequently stabilised between MCI and ATD. This is not the case with total tau and phosphorylated tau levels, which increase with disease progression.5 In our study, 18% of controls, 64% of patients with MCI, and 92% of patients with ATD were A+; this is consistent with the literature.26 Neurodegeneration without amyloidosis, which suggests non-AD pathophysiology, has been described as SNAP6 and was found in 11% of controls, 6% of patients with MCI, and 8% of those with ATD in our sample. These findings are consistent with those of the ADNI study,27 which reported SNAP in 17% of patients with MCI and in 7% of those with ATD. According to some authors,28 MCI due to AD is indistinguishable from MCI associated with SNAP in terms of clinical characteristics, risk factors, and prognosis. Depending on whether amyloidosis was present, we divided our sample into 2 groups: patients with MCI due to AD (A+) and patients without AD (A−); both groups were similar in terms of age, education level, sex distribution, and global cognitive function (MMSE) at baseline. In line with the findings reported by Caroli et al.,28 no differences were observed in neuropsychiatric symptoms, functional ability, or global cognitive function, except for delayed recall. Likewise, we found no differences in hippocampal volume.

Seventy-five percent of patients with amyloidosis carried at least one APOE ɛ4 allele, compared to only 16% of those without amyloidosis. These results are similar to those of the ADNI study,29 which reports that 70.6% of A+ patients were carriers, compared to 18.7% among A− patients. Approximately 10% of patients with abnormally low CSF Aβ1-42 levels show normal amyloid PET results. This contrast has been explained by the fact that these 2 methods detect amyloid deposition at different stages: according to the literature, low CSF Aβ1-42 levels are detected before amyloid PET results become abnormal.30 During the 30-month follow-up, MCI progressed to dementia in 34.7% of patients, with considerable differences between A+ and A− patients: progression to dementia was observed in 45% patients with amyloidosis (MCI due to AD) vs 20% of those without. Although nearly half of all A+ patients developed dementia, the rate of progression to dementia in patients with MCI not due to AD was significantly higher than that of controls, as reported in other studies.27,28 This is especially relevant in clinical practice: amyloidosis in a patient with MCI is suggestive of AD, but absence of amyloidosis does not rule out disease; rather, it suggests other non-AD conditions, as reported by some authors31 who have proposed the term “primary age-related tauopathy” (PART). According to Duyckaerts et al.,32 there is no evidence that PART and AD are 2 discrete entities. Further research is needed to resolve this controversy.

Our study has several limitations, including the short follow-up period (30 months) and a small sample of patients (the 40 patients of the Argentinian ADNI cohort1). However, the lack of data from our region confers validity to our preliminary results, pending further studies with larger samples.

ConclusionsAD biomarkers are improving our understanding of the pathophysiology of AD, and probably constitute the cornerstone of future treatment for the condition. Gathering data from Latin America will allow us to compare the situation of AD in our setting to that of developed countries, increasing our knowledge of the disease for clinical practice.

FundingThis study received funding from the FLENI Foundation (Buenos Aires, Argentina).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Allegri RF, Chrem Mendez P, Russo MJ, Cohen G, Calandri I, Campos J, et al. Biomarcadores de enfermedad de Alzheimer en deterioro cognitivo leve: experiencia en una clínica de memoria de Latinoamérica. Neurología. 2021;36:201–208.