This paper analyses the correlations between scores on scales assessing impairment, psychological distress, disability, and quality of life in patients with peripheral facial palsy (PFP).

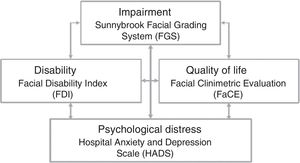

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study including 30 patients in whom PFP had not resolved completely. We used tools for assessing impairment (Sunnybrook Facial Grading System [FGS]), psychological distress (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]), disability (Facial Disability Index [FDI]), and quality of life (Facial Clinimetric Evaluation [FaCE] scale).

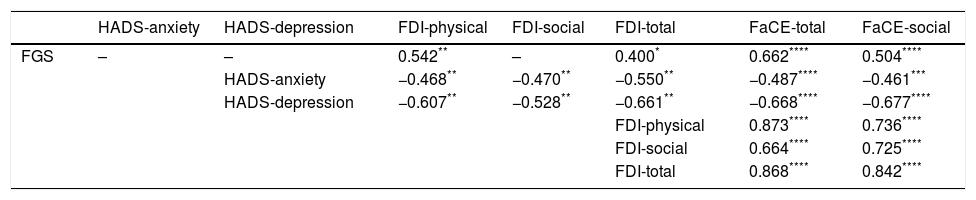

ResultsWe found no correlations between FGS and HADS scores, or between FGS and FDI social function scores. However, we did find a correlation between FGS and FDI physical function scores (r=0.54; P<.01), FDI total score (r=0.4; P<.05), FaCE total scores (ρ=0.66; P<.01), and FaCE social function scores (ρ=0.5; P<.01). We also observed a correlation between HADS Anxiety scores and FDI physical function (r=−0.47; P<.01), FDI social function (r=−0.47; P<.01), FDI total (r=−0.55; P<.01), FaCE total (ρ=−0.49; P<.01), and FaCE social scores (ρ=−0.46; P<.05). Significant correlations were also found between HADS Depression scores and FDI physical function (r=−0.61; P<.01), FDI social function (r=−0.53; P<.01), FDI total (r=−0.66; P<.01), FaCE total (ρ=−0.67; P<.01), and FaCE social scores (ρ=−0.68; P<.01), between FDI physical function scores and FaCE total scores (ρ=0.87; P<.01) and FaCE social function (ρ=0.74; P<.01), between FDI social function and FaCE total (ρ=0.66; P<.01) and FaCE social function scores (ρ=0.72; P<.01), and between FDI total scores and FaCE total (ρ=0.87; P<.01) and FaCE social function scores (ρ=0.84; P<.01).

ConclusionIn our sample, patients with more severe impairment displayed greater physical and global disability and poorer quality of life without significantly higher levels of social disability and psychological distress. Patients with more disability experienced greater psychological distress and had a poorer quality of life. Lastly, patients with more psychological distress also had a poorer quality of life.

El objetivo de este trabajo es analizar la correlación entre escalas de deficiencia, afectación psicológica, discapacidad y calidad de vida en personas que han sufrido una parálisis facial periférica (PFP).

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio transversal retrospectivo con 30 pacientes que habían presentado una PFP cuya resolución fue incompleta. Se utilizaron cuestionarios de deficiencia (Sunnybrook Facial Grading System [FGS]), afectación psicológica (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS]), discapacidad (Facial Disability Index [FDI]) y calidad de vida (Facial Clinimetric Evaluation Scale [FaCE]).

ResultadosNo encontramos correlación entre FGS y HADS, ni entre FGS y FDI Social. Existe correlación entre FGS y FDI Física (r=0,54; p<0,01), FDI total (r=0,4; p<0,05), FaCE total (ρ = 0,66; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = 0,5;p<0,01). Observamos correlación entre HADS Ansiedad y FDI Física (r=−0,47; p<0,01), FDI Social (r=−0,47; p<0,01), FDI Total (r=−0,55; p<0,01), FaCE Total (ρ = −0,49; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = −0,46; p<0,05). También entre HADS Depresión y FDI Física (r=−0,61; p<0,01), FDI Social (r=−0,53; p<0,01), FDI Total (r=−0,66; p<0,01), FaCE Total (ρ = −0,67; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = −0,68; p<0,01). Encontramos correlación entre FDI Física y FaCE Total (ρ = 0,87; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = 0,74; p<0,01), FDI Social y FaCE Total (ρ = 0,66; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = 0,72; p<0,01), y FDI Total y FaCE Total (ρ = 0,87; p<0,01) y FaCE Social (ρ = 0,84; p<0,01).

ConclusiónEn nuestro grupo de estudio, los pacientes con mayor déficit presentan mayor discapacidad física y global y peor calidad de vida, aunque no mayor discapacidad social ni mayor afectación psicológica. Los pacientes con mayor discapacidad presentan mayor afectación psicológica y peor calidad de vida. Los pacientes con mayor afectación psicológica presentan peor calidad de vida.

Although peripheral facial palsy (PFP) rarely has a significant impact on daily life, the experience is always traumatic. Some patients may even need to redefine their social and/or professional relationships and their own identity. This is explained by the fact that socially, the face is one of the most important parts of the body. Firstly, it is an individual's most distinctive feature.1,2 Secondly, it is central to how individuals see themselves and how they are seen by the people around them.1–4 Lastly, the face is essential to social interaction.1,4

Although PFP is a recognised cause of disability and psychological distress and reduces patients’ quality of life, the assessment instruments used in clinical practice (e.g., Sunnybrook Facial Grading System, House-Brackmann scale) focus on impairment exclusively, disregarding the disability, the impact on quality of life, and patients’ subjective perceptions regarding the condition. According to several authors, acoustic neuroma causes psychological distress5,6 and, most importantly, decreases quality of life6–10; however, other authors report no impact on the patient's psychological status11,12 or quality of life.11,13 Regarding PFP specifically, various studies report that the condition has a negative impact on psychological status14–16 and quality of life,17 although other researchers have found no such association.18

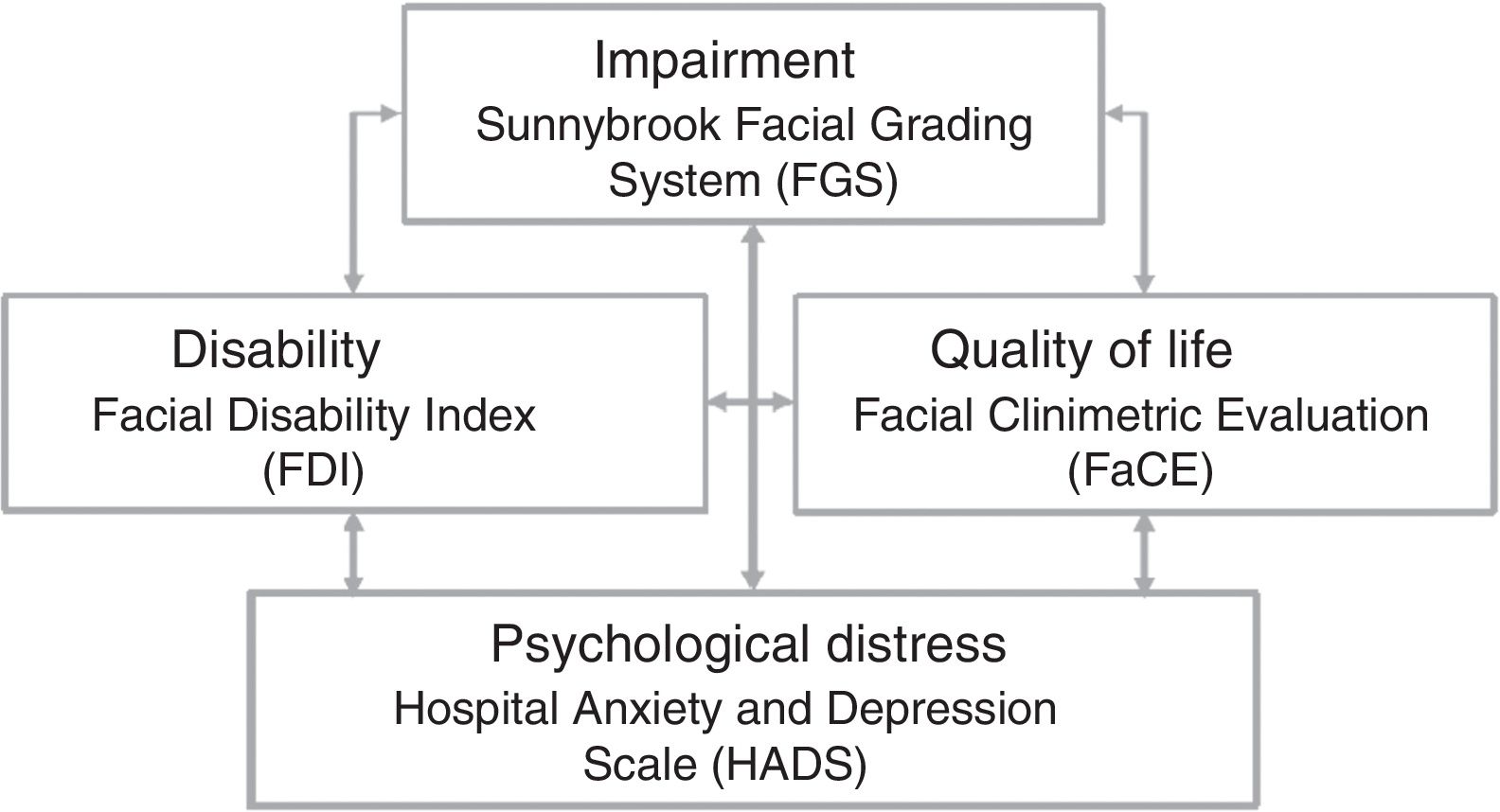

This study analyses the correlation between the results of different scales assessing impairment, psychological distress, disability, and quality of life in patients with incompletely resolved PFP (Fig. 1).

Material and methodsThis retrospective, cross-sectional study included 30 patients with incompletely resolved PFP. The sample included outpatients assessed between July 2014 and October 2015 at the rehabilitation and physical medicine department of Xarxa Sanitària i Social Santa Tecla in Tarragona (Spain). The inclusion criteria were as follows: age 18 years and above, progression time of at least 6 months, incomplete resolution of PFP, and consent to participate in the study by completing the questionnaires.

The scales and questionnaires used were:

- –

The Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (FGS): this scale measures the degree of impairment caused by PFP. Scores range from 0 to 100, with 100 points indicating normal function; the scale assesses movement, symmetry, and synkinesis.19

- –

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS): this questionnaire assesses psychological distress (anxiety and/or depression) in hospitalised patients. This is a screening rather than a diagnostic tool. It comprises 2 subscales (one for anxiety and the other for depression); both are scored from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher levels of anxiety/depression. Scores of 0 to 7 points are regarded as normal (no anxiety/depression), 8 to 10 as borderline abnormal, and 11 to 21 as abnormal (presence of anxiety/depression).20,21

- –

The Facial Disability Index (FDI): this questionnaire evaluates disability caused by PFP. The instrument includes 2 subscales for evaluating physical and social function and is scored from 0 to 100, where a score of 100 indicates normal function.22,23

- –

The Facial Clinimetric Evaluation (FaCE): this questionnaire evaluates quality of life in patients with PFP. The scale includes several domains (facial movement, facial comfort, oral function, eye comfort, lacrimal control, and social function) and is scored from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life.24

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS statistics software, version 17.0. Normal distribution was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used for parametric data and the Spearman correlation coefficient for non-parametric data. The level of statistical significance was set at P<.05.

This study was approved by the relevant clinical research ethics committee (reference no. C.I. 20/2016).

ResultsSample characteristicsThe sample included 30 patients (7 men, 23 women), with PFP affecting the left side in 12 patients and the right in 18. PFP was caused by surgery in 7 patients (4 with acoustic neuroma, 2 with otitis, one with a parotid tumour), face trauma in one, Bell's palsy in 17, herpes zoster infection in 4, and otitis in one.

Patients had a mean age of 51.1±16.02 years (range, 18-80). Mean disease progression time was 102±197.23 months (range, 6-752). Twenty-four participants underwent an electroneurography study at disease onset; the study revealed a mean amplitude loss of 70.2%±18.74% (range, 40%-100%). Eighteen participants (60%) presented normal HADS anxiety scores, 7 (23%) presented borderline abnormal scores, and 5 (17%) had anxiety; 25 patients (83%) presented normal HADS depression scores, 3 (10%) presented borderline abnormal scores, and 2 (7%) had depression.

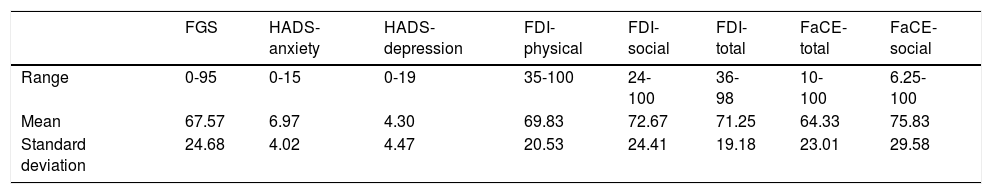

Table 1 summarises patients’ scores on the scales measuring impairment (FGS), psychological distress (HADS), disability (FDI), and quality of life (FaCE).

Patients’ scores on the scales measuring impairment, psychological distress, disability, and quality of life.

| FGS | HADS-anxiety | HADS-depression | FDI-physical | FDI-social | FDI-total | FaCE-total | FaCE-social | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | 0-95 | 0-15 | 0-19 | 35-100 | 24-100 | 36-98 | 10-100 | 6.25-100 |

| Mean | 67.57 | 6.97 | 4.30 | 69.83 | 72.67 | 71.25 | 64.33 | 75.83 |

| Standard deviation | 24.68 | 4.02 | 4.47 | 20.53 | 24.41 | 19.18 | 23.01 | 29.58 |

We found no statistically significant correlation between impairment (FGS) and psychological distress (HADS), nor between impairment (FGS) and social disability (FDI, social function). Impairment (FGS) showed a statistically significant moderate correlation with physical disability (FDI, physical function) and with global disability (total FDI). We also found a statistically significant correlation between impairment (FGS) and overall (total FaCE) and social quality of life (FaCE, social function) (Table 2).

Statistically significant correlations between impairment, psychological distress, disability, and quality of life.

| HADS-anxiety | HADS-depression | FDI-physical | FDI-social | FDI-total | FaCE-total | FaCE-social | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGS | – | – | 0.542** | – | 0.400* | 0.662**** | 0.504**** |

| HADS-anxiety | −0.468** | −0.470** | −0.550** | −0.487**** | −0.461*** | ||

| HADS-depression | −0.607** | −0.528** | −0.661** | −0.668**** | −0.677**** | ||

| FDI-physical | 0.873**** | 0.736**** | |||||

| FDI-social | 0.664**** | 0.725**** | |||||

| FDI-total | 0.868**** | 0.842**** |

Psychological distress (HADS) showed a statistically significant, moderate negative correlation with physical (FDI, physical function), social (FDI, social function), and global disability (total FDI). A statistically significant, moderate negative correlation was observed between psychological distress (HADS) and overall (total FaCE) and social quality of life (FaCE, social function).

A statistically significant positive correlation was also found between physical (FDI, physical function), social (FDI, social function), and global disability (total FDI), and overall (total FaCE) and social quality of life (FaCE, social function).

DiscussionWe observed no significant association between the level of impairment and psychological distress; this is consistent with results from previous studies.5,11,14,18 However, other researchers do report an association between PFP-related impairment and psychological distress.15

We identified a moderate positive correlation between the level of impairment and physical and global disability, but not with social disability. Results reported by van Swearingen et al.25 support our own, although those researchers did find a positive correlation between FGS scores and all FDI domains (physical function, social function, and total score).

We also observed a moderate positive correlation between level of impairment and social and overall quality of life. Some researchers report similar results to our own,24,26,27 while others did not find these correlations.11,13 Some studies have found an association between the level of impairment and overall quality or life, but not with social quality of life.9,17

We also found a moderate negative correlation between psychological distress and physical, social, and global disability, and also between psychological distress and social and overall quality of life. To our knowledge, no previous study has addressed the association between psychological distress and disability, or between psychological distress and quality of life.

Lastly, we found a strong positive correlation between physical, social, and global disability and social and overall quality of life; this is consistent with the results reported by Volk et al.17

The lack of association between impairment and psychological distress, and between impairment and social disability, may be due to the small size of our sample; however, discrepancies in the results of previous studies finding a correlation and those failing to do so are independent of sample size. Psychological distress is difficult to analyse, and the questionnaire used may have biased our results. Qualitative tools, such as an interview, may provide further data.

Another limitation of our study is the fact that the FaCE scale is not validated in Spanish; the correlations between quality of life and impairment, psychological distress, and disability should therefore be analysed with caution. A validated Spanish-language version of the FaCE scale would constitute a significant advance in the study of quality of life in patients with PFP. The external validity of our study may be biased by the fact that all participants were outpatients of the rehabilitation department. Patients with more severe psychological distress, greater disability, and poorer quality of life tend to seek medical care more frequently.

A number of factors may influence psychological distress, functional ability, and quality of life in patients with PFP. There is controversy in the literature as to the relevance of these factors. Although PFP severity is perceived as an important factor, both our results and those of other studies show that this is not always the case.5,11,13,18 The same is true of age: several authors have found age to be associated with psychological distress and quality of life,4 while others have failed to find such an association.9,14 Some studies report an association between sex and psychological distress and quality of life,5,14–16,27 while others do not.9,26 Kleiss et al.27 found an association between progression time and quality of life, whereas most studies report no such association.5,9,16,18

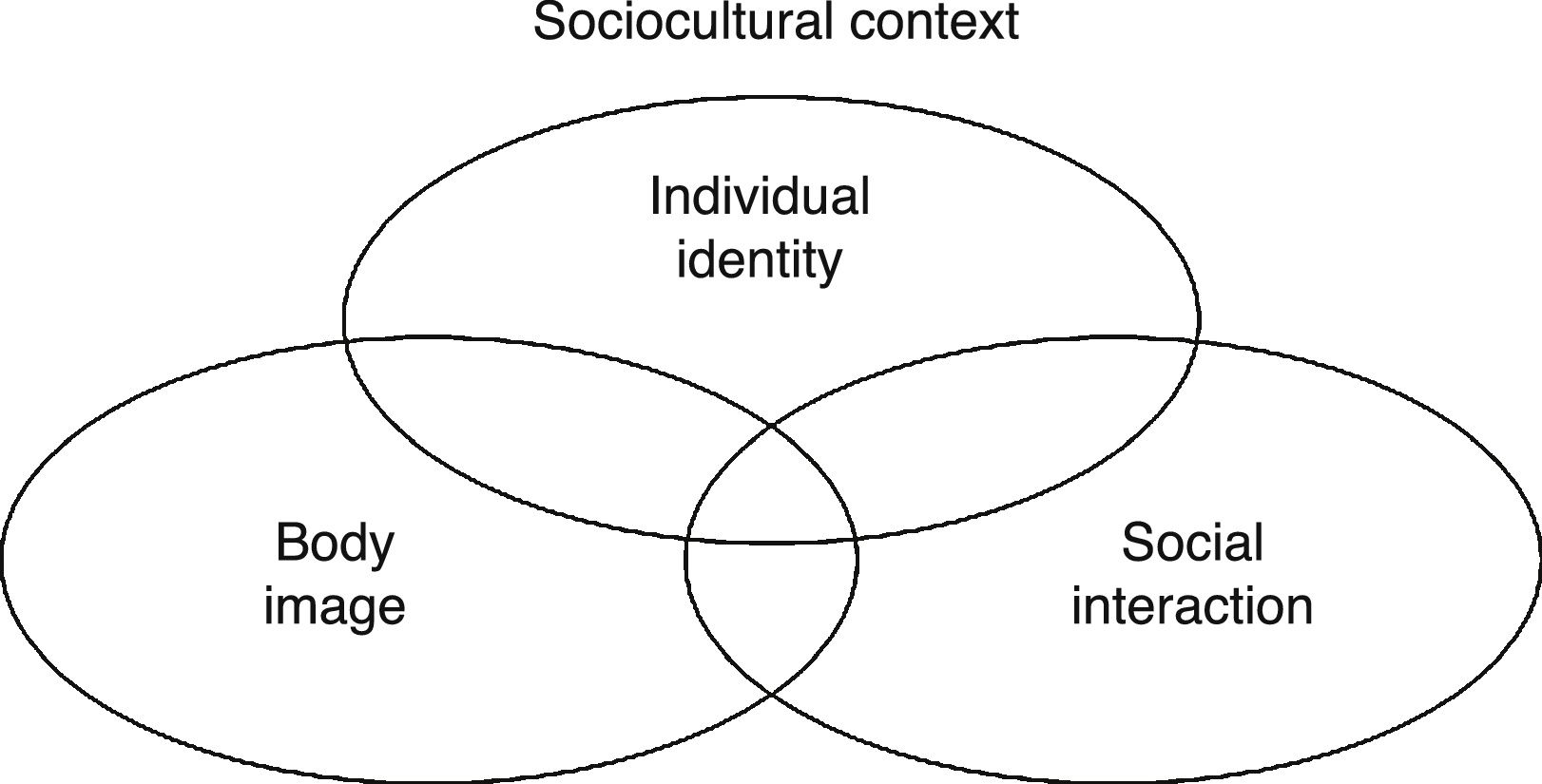

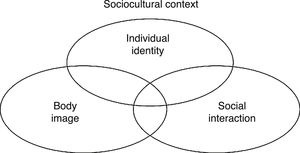

Although these variables strongly influence psychological distress, functional ability, and quality of life, perhaps the key aspect of PFP is the fact that the face is one of the most important parts of the body socially. PFP influences social dimensions including identity,1,2 body image (both self-image and how others see us),1–4 and social interaction and communication.1,3 These dimensions are interrelated and framed within a specific sociocultural context (Fig. 2). Facial disfigurement is not a disability since it does not affect an individual's competence, although it may be regarded as such in that it hinders socialisation (social disability).2

In an individualistic society, the face is the body part that most identifies us as individuals, since it is sufficiently powerful and variable to differentiate one person from another. The value of the face as an element of identity increases in parallel with the societal importance of individuality. The level of social disability caused by PFP depends on the level of individualism within a person's social group and the importance they place on their face as a part of their identity. PFP is perceived as an event that threatens a person's identity, as a deprivation of being.1,2

Body image (both self-image and how others see us) is determined by the beauty standards of a specific sociocultural environment. In our society, the predominant canon of beauty establishes that a body must be perfect, beautiful, and healthy; this is particularly the case for women, who are under greater pressure to meet these standards.1,2 According to the ideal of beauty, the face should be well-balanced and proportionate.28 PFP alters these characteristics, representing an attack on the prevailing model of beauty and affecting body image. The impact of PFP depends on the prevalent ideal of beauty in a person's social setting and how internalised that ideal is in the individual. Although women and young people are thought to show greater psychological distress, more severe disability, and poorer quality of life, the impact of PFP is neither sex- nor age-dependent; rather, the impact of the condition depends on the degree of internalisation of the beauty canon, which tends to be higher among these groups.

Regarding social interaction, the face constitutes an essential element in any society. Day-to-day social activity involves face-to-face interaction, with the face becoming a stage that displays emotions and generates mutual recognition.1,4 The face is also a fundamental tool in communication, with facial expression complementing, preceding, or even contradicting words.1,4 Patients with PFP experience changes or difficulties in social interaction that may lead to social disability. The condition may become a stigma, a “deeply discrediting” attribute29 that pervades face-to-face interaction. Stigmatised individuals develop such social strategies as disguising, concealing, or exhibiting the condition, or even withdrawing from society.1,2,29

As mentioned previously, the tools used in clinical practice measure impairment exclusively, disregarding the impact of PFP on a patient's quality of life or psychological status. We observed no correlation between impairment and psychological distress or between impairment and social disability. Furthermore, although we did detect an association between impairment and quality of life, other studies seem to contradict this correlation, at least partially.9,11,13,17 We recommend using complementary tools, such as the FaCE, for quality of life; low FaCE scores are strongly correlated with impairment, disability, and psychological distress, although the scale is yet to be validated in Spanish.

ConclusionIn our sample, patients with more severe PFP showed more severe physical and global disability and poorer social and overall quality of life. However, these patients did not show greater social disability or psychological distress (anxiety or depression). Furthermore, patients with more severe physical, social, and global disability showed higher levels of psychological distress in the form of anxiety or depression, and poorer social and overall quality of life. Patients with greater psychological distress had poorer social and overall quality of life.

Impairment caused by PFP may cause difficulties in several social dimensions, particularly in a person's sense of identity, body image, and social interaction, with consequences for functional ability, psychological status, and quality of life. Assessment should therefore focus on domains other than impairment, both in clinical practice and in research.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Díaz-Aristizabal U, Valdés-Vilches M, Fernández-Ferreras TR, Calero-Muñoz E, Bienzobas-Allué E, Moracén-Naranjo T. Correlación entre deficiencia, afectación psicológica, discapacidad y calidad de vida en la parálisis facial periférica. Neurología. 2019;34:423–428.