To identify impairment of executive functions (EFs) in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Subjects and methodsA case-control study was performed on a sample of schoolchildren with low socioeconomic levels in Bogota, Colombia. ADHD was diagnosed using the DSM IV checklist and the Behaviour Assessment System for Children (BASC) scale. Children with cognitive deficits were excluded. We evaluated scores from six measurements of EF. We conducted a bivariate statistical analysis to compare the variables, a multivariate study controlled by sex and age, and a logistic regression analysis.

ResultsThe study sample included 119 children with ADHD and 85 controls, all aged between 6 and 12 years. Controlling by sex, age, and type of school showed that EF measurements in children with ADHD were significantly more impaired than in controls, especially for measurements of verbal and graphic fluency, Rey-Osterrieth complex figure, and cognitive flexibility. Comparison of ADHD subgroups showed that results in children with multiple deficits were similar to those in the global ADHD group. Graphic fluency impairment was the sole impairment in cases with only attention deficit or only hyperactivity-impulsivity manifestations.

ConclusionsEF measures in children with ADHD revealed more problems, particularly those having to do within planning, inhibition, working memory and cognitive control. Age and sex may affect the degree of EF impairment.

Determinar las alteraciones de las funciones ejecutivas (FE) en niños con trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad (TDAH).

Sujetos y métodosSe realizó un estudio de casos y controles con una muestra de estudiantes de colegios de Bogotá, Colombia, pertenecientes a los estratos socioeconómicos bajos. El diagnóstico de TDAH se realizó con la lista de chequeo del DSM IV y la escala multidimensional de BASC. Se descartaron los niños que presentaban trastornos cognitivos. Se evaluó el desempeño en 6 medidas de funciones ejecutivas. Se realizaron un análisis bivariado entre variables, un estudio multivariado controlado por sexo y edad, y una regresión logística condicional.

ResultadosSe estudió a 119 niños con síntomas de TDAH y 85 controles con edades comprendidas entre 6 y 13 años. Cuando se controlaron por sexo, edad y tipo de colegio, los niños con TDAH tuvieron un mayor compromiso que los controles en las medidas de FE correspondientes a fluidez verbal y gráfica, figura compleja de Rey-Osterrieth y flexibilidad cognitiva. Cuando se compararon los subgrupos de TDAH, no hubo diferencias entre el grupo mixto con el general. Los casos con inatención sola e hiperactividad-impulsividad sola presentaron dificultades en fluidez gráfica.

ConclusionesLos niños con síntomas de TDAH presentan mayores problemas en medidas de las FE especialmente en planeación, inhibición, memoria de trabajo y control cognitivo. Parece existir posiblemente una heterogeneidad entre el trastorno de las FE respecto del sexo y la edad.

Attention is the ability to select stimuli that are relevant to an individual in a concrete situation. This ability depends on the degree of maturation of the structures and functional systems that permit an alert state and filtering of information in the central nervous system, and it is therefore an important component of the basic mechanisms in learning.1 Meanwhile, executive functions (EFs) are defined as the ability to plan, direct, orient, guide, coordinate, and organise joint actions by different elements to achieve an end or goal.2

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a nosological entity with a high morbidity and prevalence. It constitutes the most common chronic disease among school-age children, and the problem it poses is complex given that the disease appears at a young age, affects the child's daily life, and may persist throughout the patient's lifetime.3–5 Many studies have shown that there is a relationship between ADHD and performance of EFs.6–8 This being the case, a child with attention deficit disorder will experience difficulty organising his motor and cognitive behaviour. This difficulty manifests as inability to follow orders and as long wait times before performing actions and tasks, which the child finally completes in a disorderly, impulsive manner.9–11

From an aetiological viewpoint, researchers often study dopamine receptors and, in general, the pathways engaging in catecholamine metabolism, which may be altered both in ADHD and in cases of certain executive dysfunctions.12

We would like to point out that ADHD may coexist with a number of disorders, such as learning, behavioural, or mood disorders, and with Tourette syndrome, to name a few. Executive dysfunction in these children may also be present without any of these comorbidities manifesting.13–15

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between ADHD and EF performance in a population of schoolchildren from Bogotá.

Subjects and methodsWe performed an analytical observational case-control study building on an earlier cross-sectional study to determine the prevalence of neuropaediatric diseases in children representing socioeconomic levels 1 to 4 [low to middle] in public and private schools in Bogotá. Children who showed symptoms of ADHD according to the DSM IV check-list validated for Colombia16 were included. We also included a number of children suspected of having the disorder based on responses on surveys given to parents and teachers. The diagnosis was verified using the BASC scale (Behaviour Assessment System for Children).17 Since there was little concordance between assessments applied by parents and teachers, we opted to separate results on attention/hyperactivity scales completed by parents from those completed by teachers to determine the final case group. Children had to meet the following requirements for selection:

- –

Schoolchild fulfilling at least 6 of 9 criteria on the parent-applied check-list for poor attention and a percentile ≥85 on the attention domain of the BASC attention scale applied by parents or teachers; or

- –

Schoolchild meeting at least 6 of 9 criteria on the parent-applied check-list for hyperactivity and a percentile ≥85 on the attention domain of the BASC attention scale applied by parents or teachers.

All children took the WISC-R test (Weschler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised) to rule out any possible cases of cognitive deficiency; IQ<70 was considered the cut-off point. To form the control group, we evaluated children regarded as normal who were in the same years at school as children in the affected group. Controls did not meet criteria for ADHD according to DSM IV and the BASC.

In evaluating EFs, we selected and applied subtests from ENI (Evaluación Neuropsicológica Infantil) to both subjects and controls. This childhood neuropsychological assessment examines the child's ability to plan, structure, and carry out different types of tasks involving abilities related to semantics, vocabulary use, representational skills, copying figures or creating them without a model by following instructions, set learning ability, and ability to shift sets when so instructed by the examiner.18

Information was analysed using SPSS version 19.0 for Windows. All researchers received prior training to ensure data quality. During fieldwork, we stressed the importance of filling in the forms completely and ensured that at least one of the researchers was available to answer any questions that came up. During the data entry process, we took a random sample of 10% of the entries and ran a consistency check to ensure there were no inconsistencies.

Frequency distributions and percentages were used in the descriptive analysis of qualitative variables. Measures of central tendency and variability and their respective coefficients of variation were used to measure data homogeneity in quantitative variables. The association between EF findings and ADHD was assessed using the uncorrected chi-square test. Using data with probability values <0.20, we performed a conditional logistic regression analysis or a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA).

This was a no-risk study which complied with our country's legal and ethical directives as well as those stated in the latest version of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki. Families participated voluntarily and all children's parents signed an informed consent form; children also assented. The study was approved by the research ethics committee at Universidad del Rosario. All children received a report with their results. Counselling sessions were held with parents whose children scored below 70 on the IQ test to provide advice on how best to manage the situation.

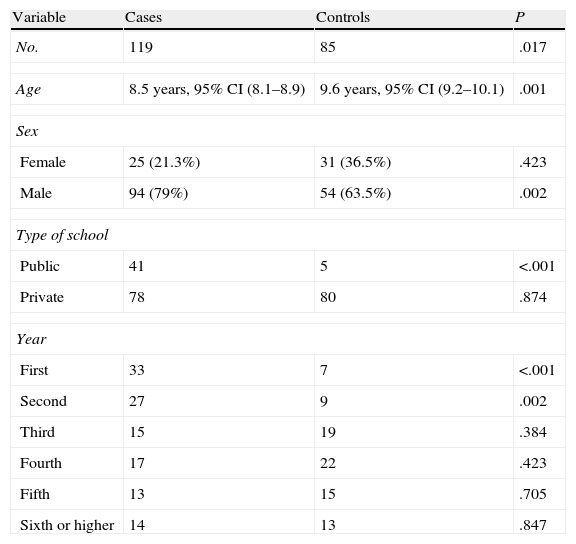

ResultsSigned consent forms were obtained for 250 children. Of this number, 35 were excluded due to data being incomplete or inconclusive for ADHD; 1 due to the child being under six; and 10 due to having an IQ below 70. The final sample was composed of 119 cases and 85 controls, including 148 males and 56 females (2.6:1) (Table 1). The case–control ratio in males showed a significantly higher number of cases (P=.002), which was not found among females.

Demographic variables.

| Variable | Cases | Controls | P |

| No. | 119 | 85 | .017 |

| Age | 8.5 years, 95% CI (8.1–8.9) | 9.6 years, 95% CI (9.2–10.1) | .001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 25 (21.3%) | 31 (36.5%) | .423 |

| Male | 94 (79%) | 54 (63.5%) | .002 |

| Type of school | |||

| Public | 41 | 5 | <.001 |

| Private | 78 | 80 | .874 |

| Year | |||

| First | 33 | 7 | <.001 |

| Second | 27 | 9 | .002 |

| Third | 15 | 19 | .384 |

| Fourth | 17 | 22 | .423 |

| Fifth | 13 | 15 | .705 |

| Sixth or higher | 14 | 13 | .847 |

ADHD subgroup classifications could be applied in 107 cases: 35 (29.9%) were inattentive type, 11 (9.4%) were hyperactive/impulsive type, and 63 (52.9%) were combined type. Incongruous results meant that 10 cases could not be categorised. We studied children representing every year of primary school and found a difference in the case–control ratio among the youngest children, but this did not create problems when it came time to run analyses.

Mean age±standard deviation was 9±2.26 years (6–15). Results showed that controls were an average of 1.11 years older (0.49–1.72) than cases (P<.001) (Table 1). Regarding age distribution in the sample, we found that controls displayed a normal curve (P=.13) while the cases demonstrated a deviation towards the youngest children (P=.006).

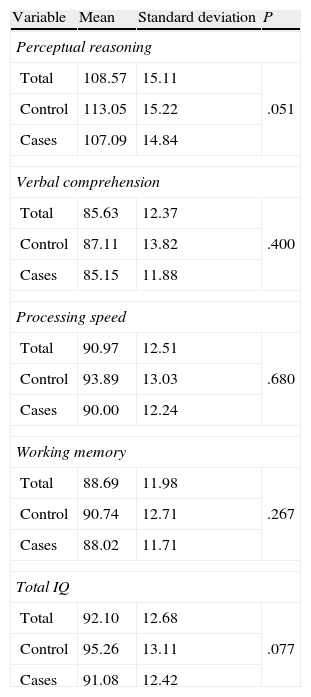

The WISC score in the study group was 92.1, which was in the average range. We found that cases had lower scores than controls but differences were not statistically significant (Table 2).

Scores on the WISC test.

| Variable | Mean | Standard deviation | P |

| Perceptual reasoning | |||

| Total | 108.57 | 15.11 | .051 |

| Control | 113.05 | 15.22 | |

| Cases | 107.09 | 14.84 | |

| Verbal comprehension | |||

| Total | 85.63 | 12.37 | .400 |

| Control | 87.11 | 13.82 | |

| Cases | 85.15 | 11.88 | |

| Processing speed | |||

| Total | 90.97 | 12.51 | .680 |

| Control | 93.89 | 13.03 | |

| Cases | 90.00 | 12.24 | |

| Working memory | |||

| Total | 88.69 | 11.98 | .267 |

| Control | 90.74 | 12.71 | |

| Cases | 88.02 | 11.71 | |

| Total IQ | |||

| Total | 92.10 | 12.68 | .077 |

| Control | 95.26 | 13.11 | |

| Cases | 91.08 | 12.42 | |

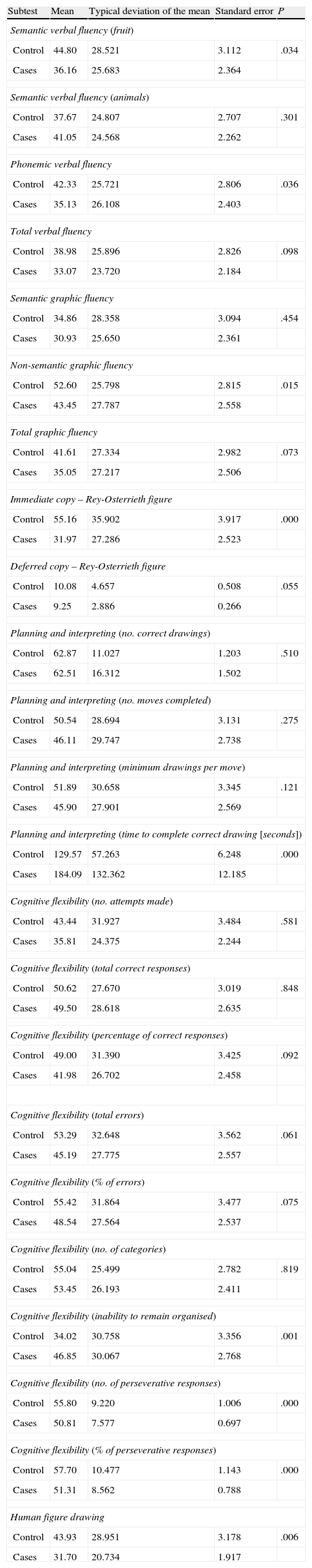

A decrease in percentiles on EF test scores was also observed among cases except for the semantic verbal fluency test (animal naming). This difference was significant for semantic verbal fluency (types of fruit) and phonemic verbal fluency; non-semantic graphic fluency; Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test; planning and interpretation time in seconds to complete the drawing correctly; cognitive flexibility (inability to remain organised, perseverative responses), and human figure drawing (Table 3).

Evaluation of executive function tests in ADHD cases and controls.

| Subtest | Mean | Typical deviation of the mean | Standard error | P |

| Semantic verbal fluency (fruit) | ||||

| Control | 44.80 | 28.521 | 3.112 | .034 |

| Cases | 36.16 | 25.683 | 2.364 | |

| Semantic verbal fluency (animals) | ||||

| Control | 37.67 | 24.807 | 2.707 | .301 |

| Cases | 41.05 | 24.568 | 2.262 | |

| Phonemic verbal fluency | ||||

| Control | 42.33 | 25.721 | 2.806 | .036 |

| Cases | 35.13 | 26.108 | 2.403 | |

| Total verbal fluency | ||||

| Control | 38.98 | 25.896 | 2.826 | .098 |

| Cases | 33.07 | 23.720 | 2.184 | |

| Semantic graphic fluency | ||||

| Control | 34.86 | 28.358 | 3.094 | .454 |

| Cases | 30.93 | 25.650 | 2.361 | |

| Non-semantic graphic fluency | ||||

| Control | 52.60 | 25.798 | 2.815 | .015 |

| Cases | 43.45 | 27.787 | 2.558 | |

| Total graphic fluency | ||||

| Control | 41.61 | 27.334 | 2.982 | .073 |

| Cases | 35.05 | 27.217 | 2.506 | |

| Immediate copy – Rey-Osterrieth figure | ||||

| Control | 55.16 | 35.902 | 3.917 | .000 |

| Cases | 31.97 | 27.286 | 2.523 | |

| Deferred copy – Rey-Osterrieth figure | ||||

| Control | 10.08 | 4.657 | 0.508 | .055 |

| Cases | 9.25 | 2.886 | 0.266 | |

| Planning and interpreting (no. correct drawings) | ||||

| Control | 62.87 | 11.027 | 1.203 | .510 |

| Cases | 62.51 | 16.312 | 1.502 | |

| Planning and interpreting (no. moves completed) | ||||

| Control | 50.54 | 28.694 | 3.131 | .275 |

| Cases | 46.11 | 29.747 | 2.738 | |

| Planning and interpreting (minimum drawings per move) | ||||

| Control | 51.89 | 30.658 | 3.345 | .121 |

| Cases | 45.90 | 27.901 | 2.569 | |

| Planning and interpreting (time to complete correct drawing [seconds]) | ||||

| Control | 129.57 | 57.263 | 6.248 | .000 |

| Cases | 184.09 | 132.362 | 12.185 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (no. attempts made) | ||||

| Control | 43.44 | 31.927 | 3.484 | .581 |

| Cases | 35.81 | 24.375 | 2.244 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (total correct responses) | ||||

| Control | 50.62 | 27.670 | 3.019 | .848 |

| Cases | 49.50 | 28.618 | 2.635 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (percentage of correct responses) | ||||

| Control | 49.00 | 31.390 | 3.425 | .092 |

| Cases | 41.98 | 26.702 | 2.458 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (total errors) | ||||

| Control | 53.29 | 32.648 | 3.562 | .061 |

| Cases | 45.19 | 27.775 | 2.557 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (% of errors) | ||||

| Control | 55.42 | 31.864 | 3.477 | .075 |

| Cases | 48.54 | 27.564 | 2.537 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (no. of categories) | ||||

| Control | 55.04 | 25.499 | 2.782 | .819 |

| Cases | 53.45 | 26.193 | 2.411 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (inability to remain organised) | ||||

| Control | 34.02 | 30.758 | 3.356 | .001 |

| Cases | 46.85 | 30.067 | 2.768 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (no. of perseverative responses) | ||||

| Control | 55.80 | 9.220 | 1.006 | .000 |

| Cases | 50.81 | 7.577 | 0.697 | |

| Cognitive flexibility (% of perseverative responses) | ||||

| Control | 57.70 | 10.477 | 1.143 | .000 |

| Cases | 51.31 | 8.562 | 0.788 | |

| Human figure drawing | ||||

| Control | 43.93 | 28.951 | 3.178 | .006 |

| Cases | 31.70 | 20.734 | 1.917 | |

Upon categorising EF percentile scores as either above or below the 10th percentile (the low end), we found statistically significant differences for phonemic verbal fluency (P=.044); non-semantic graphic fluency (P=.05); total graphic fluency (P=.04); and inability to remain organised (P=.01).

Examination of each group reveals that children with the inattentive type of ADHD experienced the most difficulty with non-semantic graphic fluency (P=.05) and total graphic fluency tasks (P=.01). For children with the hyperactive type, the only significantly different component was total graphic fluency (P=.03). In the combined-type group, we found changes in non-semantic and total graphic fluency (P=.038) and (P=.042); immediate copy of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure (P=.04); and in cognitive flexibility (P=.018).

Evaluating the groups by sex revealed that males showed significant differences in the immediate copy of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure (P<.001) and percentage of perseverative responses (P=.037). Females with ADHD differed from the control group in the areas of phonemic verbal fluency (P=.040), non-semantic graphic fluency (P=.036), immediate copy (P=.002) and delayed copy (P=.050) of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure, human figure drawing (P=.000), different aspects of cognitive flexibility including perseverative responses (P=.000), and inability to remain organised (P=.000). Comparing males with females did not reveal any significant differences in performance.

The multivariate analysis (MANCOVA) of EFs that were grouped and controlled by age and type of school did not show any significant differences between cases with ADHD and controls.

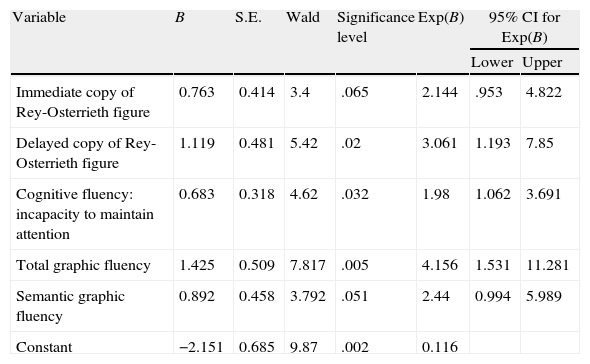

Logistic regression analysis showed that EFs related to planning and organisation, working memory, graphic fluency, and inhibition were the most compromised in patients with ADHD symptoms (Cox and Snell R2=26.5) when the model was controlled by age and type of school (Table 4).

Logistic regression analysis of executive functions.

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | Significance level | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| Immediate copy of Rey-Osterrieth figure | 0.763 | 0.414 | 3.4 | .065 | 2.144 | .953 | 4.822 |

| Delayed copy of Rey-Osterrieth figure | 1.119 | 0.481 | 5.42 | .02 | 3.061 | 1.193 | 7.85 |

| Cognitive fluency: incapacity to maintain attention | 0.683 | 0.318 | 4.62 | .032 | 1.98 | 1.062 | 3.691 |

| Total graphic fluency | 1.425 | 0.509 | 7.817 | .005 | 4.156 | 1.531 | 11.281 |

| Semantic graphic fluency | 0.892 | 0.458 | 3.792 | .051 | 2.44 | 0.994 | 5.989 |

| Constant | −2.151 | 0.685 | 9.87 | .002 | 0.116 | ||

S.E.: standard error; Exp(B): odds ratio.

Considering the discrepancies in the scores assigned by parents and teachers using the DSM IV check-list and the BASC scale, and after analysing the effect of those scores on the make-up of the definitive sample, we opted to include all children with a positive score on both scales, regardless of who categorised the child as having signs of ADHD. The researchers are aware that this decision lessens the homogeneity of the group, and that children may have been included who only show symptoms in specific situations, or who display attention deficit or hyperactivity as secondary traits. The differences in children's behaviour as perceived by either parents or teachers may be due to multiple reasons, including levels of tolerance and strictness regarding behaviour and academic performance, the course load, and ethnic, cultural, and social factors. It is important to stress the asymmetry with respect to age existing in children aged 6 to 8 who are completing their first years at school. These results are associated with factors relating to maturation, motivation, and parents’ and teachers’ expectations, as was mentioned in an earlier study.19 The marked predominance of male subjects in the study was due to the higher prevalence of ADHD in males than in females.20,21

The WISC test performed 2 functions in this study. Firstly, it excluded children whose cognitive abilities were below the normal range (IQ<70), a situation which might compromise these children's performance on other tests and be mistaken for attention deficit disorder. Secondly, it was used to gauge differences in performance between cases and controls for the total scale and for various subtests, some of which are associated with EFs. Although none of the differences were significant, we can observe that children with ADHD symptoms had lower average scores than control-group children for all subscales. In the study by Romero-Ayuso et al. which evaluated several WISC subtests in children with ADHD, children with inattentive or combined ADHD performed less well than healthy controls on tests related to working memory.22 Lambek et al. reported similar findings based on a comparison of the digit span between children with ADHD and normal controls.23

Evaluation of EFs showed overall differences in performance between cases and controls, with the latter performing more effectively. Lambek et al. found that scores for children with ADHD were statistically lower than those of children with no ADHD symptoms on every one of the tests employed.23 In China, Shuai et al. found the same results in a study of 375 boys with ADHD and 125 controls with ages ranging from 6 to 15 years.24 In our study, these differences are significant, especially in certain types of tasks requiring better planning ability and working memory. This can be seen in the verbal fluency test, requiring recall of previously acquired vocabulary that must be organised according to semantic and phonemic criteria. Such was also the case for the non-semantic graphic fluency test, the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure, and drawing a human figure, all of which require planning, attention, working memory, and programming the processes of creating drawings and complex copies. Additional significant differences were detected for set shifting, inhibitory processes, and cognitive flexibility. We should mention the study by López Campos which found that the factor structure to best explain variance in both the ADHD and the control groups consisted of the following items: categorisation, verbal fluency and sustained attention, and cognitive flexibility. These abilities were impaired in patients evaluated by our study.25 Scheres et al. found that children with ADHD showed deficits on tests of impulse control, inhibition, planning, and verbal fluency.9 However, these differences disappeared after controlling for age and sex. Lambek also determined that no sex effect was present after adjusting for age; in contrast, that study found an age effect upon controlling for sex.23 Meanwhile, Seidman observed EF impairment in association with ADHD that was independent from age and sex.7 According to the above, EFs vary with age and sex in children with ADHD. Sarkis, for example, indicates that when applying the Tower of London test, older children take less time to plan their strategies and make fewer mistakes. Regarding sex, males finish tasks more quickly than females, which may be due either to increased impulsiveness or to determining solutions more quickly.26 Our study found some sex-related differences when children with ADHD symptoms were analysed separately from controls; in the ADHD group only, performance on tests was similar between males and females.

As is common in our population, and in other countries as well, cases of combined-type ADHD predominated over the hyperactivity and inattention subtypes.14,27 When these subgroups were analysed for EF performance, we found that the combined-type subgroup's results were similar to those for the entire group. However, the inattentive and hyperactivity subgroups only showed alterations in more specific areas, especially planning ability for creating abstract figures (graphic fluency). The Chinese study by Shaui et al. reported that the combined and inattentive subtypes demonstrated impairment on multiple tasks involving inhibition, set shifting, verbal fluency, and theory of mind, while the hyperactive subtype showed greater impairment for tasks related only to visual memory and theory of mind.24 Other authors found no differences between ADHD subtypes and EF measures.28,29

Based on findings from the multivariate analysis, it is possible to infer that functions related to planning and organisation, working memory, graphic fluency, and (in part) inhibition have the greatest impact on patients with ADHD symptoms.

EFs are complex processes representing emerging abilities that are linked to age and the individual's development at the time of evaluation. This being the case, they are directly associated with the environmental stimuli in which the child has been immersed since birth. Unfortunately, there are no clear or standard guidelines for how to evaluate children in a uniform manner. Each author uses different types of tests according to a certain conceptual framework, making it difficult to compare findings from different studies. Results also show disparities when children are compared without controlling by age and sex. However, in the case of children with ADHD, findings are consistent regarding the presence of more errors in tasks related to planning, inhibition, and working memory. These factors may affect the child's learning process, and they will have to be evaluated when framing an appropriate management approach. In a study of preschoolers diagnosed with ADHD compared to a control group, Papazian et al. demonstrated that early training of EFs produces a decrease in the incidence and intensity of attention deficit and its associated learning disorders.30 It is therefore recommendable that children at risk for ADHD be screened early. Their families and schools should work together in a treatment plan aimed at developing executive abilities.

FundingThis study was completed as part of the line of research in cognitive neurosciences and partially financed by Fondo de Investigaciones de la Universidad del Rosario (Bogotá), and by Fundación para la Promoción de la Investigación y la Tecnología del Banco de la República.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Magola Delgado, director of the Formal Education division at Caja de Compensación de Colsubsidio, and to the headmasters and headmistresses of the primary schools for letting us evaluate the children.

Please cite this article as: Vélez-van-Meerbeke A, et al. Evaluación de la función ejecutiva en una población escolar con síntomas de déficit de atención e hiperactividad. Neurología.2013;28:348–55