Informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer disease (AD) have a poor health-related quality of life (HRQOL). HRQOL is an increasingly common user-focused outcome measure. We have evaluated HRQOL longitudinally in caregivers of AD patients at baseline and at 12 months.

MethodsNinety-seven patients diagnosed with AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke, and Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association) and their 97 respective primary caregivers were included in the study. We analysed the following data at the baseline visit: sociodemographic data of both patients and carers, patients’ clinical variables, and data related to the healthcare provided to patients by carers. HRQOL of caregivers was measured with the SF-36 questionnaire at baseline and 12 months later.

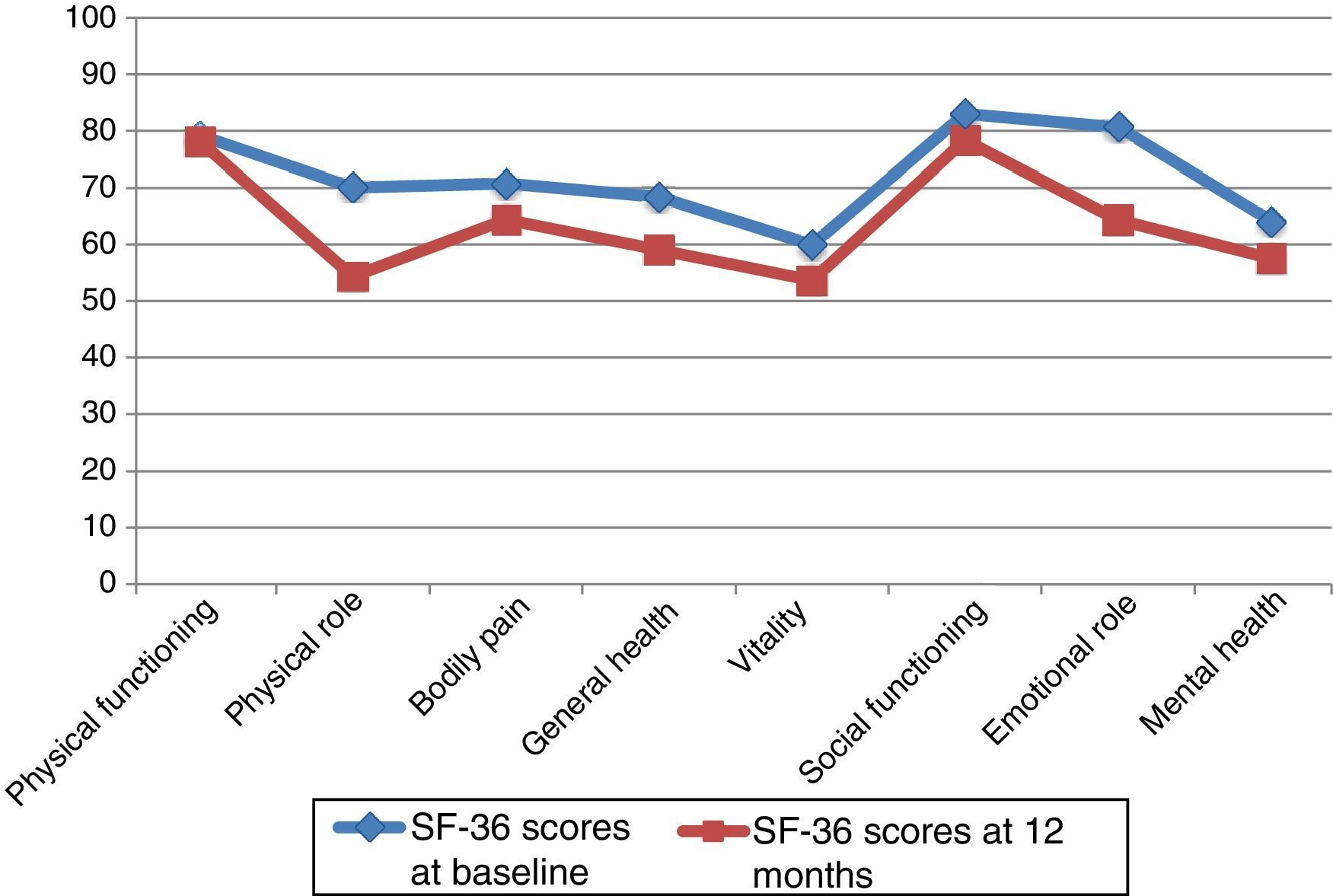

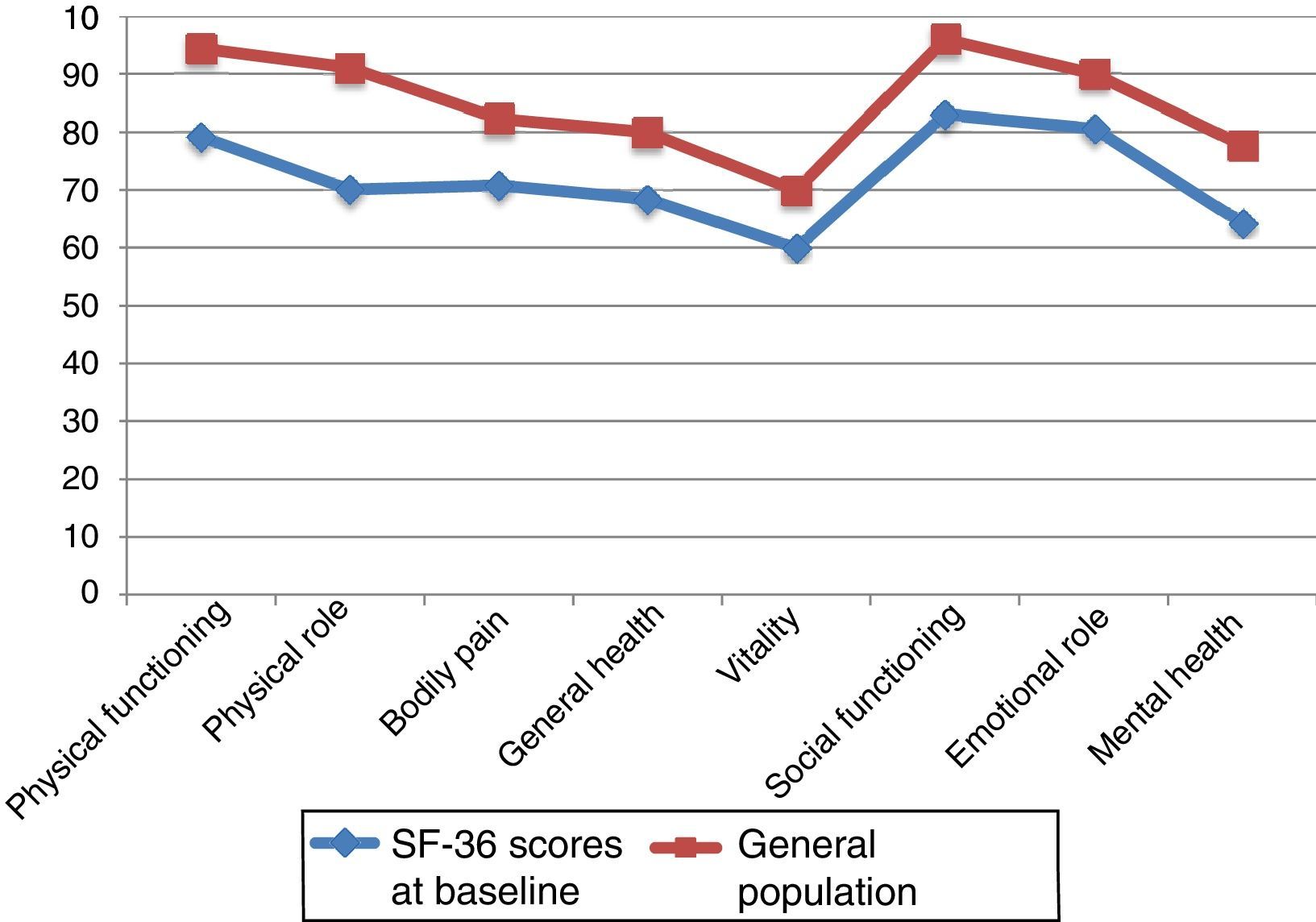

ResultsAt 12 months, primary caregivers scored lower in the 8 subscales of the SF-36 questionnaire; differences were statistically significant in all dimensions except for ‘physical function’ and ‘social function’. Baseline scores in our sample were lower than those of the general population. ‘Vitality’ is the dimension that presented the lowest scores.

ConclusionHRQOL in caregivers of patients with AD deteriorates over time and is poorer than that of the age- and sex-matched general population.

Los cuidadores de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer (EA) tienen un deterioro de su calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS). La CVRS es una medida de resultado centrada en el usuario cada vez más usada. Evaluamos de forma longitudinal la CVRS en cuidadores de pacientes con EA, antes y después, durante un periodo de 12 meses.

MétodosSe incluyó en el estudio a 97 pacientes diagnosticados de EA según criterios NINCDS-ADRDA (Instituto Nacional de Trastornos Neurológicos y de la Comunicación y Accidente Cerebrovascular y Asociación de Enfermedad de Alzheimer y Trastornos relacionados) y sus respectivos 97 cuidadores principales. Se analizaron datos sociodemográficas de ambos, clínicos de los pacientes, y datos en relación con el cuidado en la visita basal. La CVRS se midió con el cuestionario SF-36 en la visita basal y a los 12 meses.

ResultadosLas 8 dimensiones de la escala SF-36 en los cuidadores principales empeoraron de forma significativa a los 12 meses, salvo las dimensiones «Función física» y «Función social», que lo hicieron de forma no significativa. Las puntuaciones en la visita basal fueron menores que las correspondientes a la población general. La dimensión que presentó peor puntuación fue «Vitalidad».

ConclusionesLa CVRS en cuidadores de pacientes con EA empeora a lo largo de la evolución de esta y es peor que la de la población general, para su edad y género.

There is growing interest in the concept of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), especially in the context of chronic diseases, given that these conditions have no cure and survival is neither the only nor the most important outcome for these patients.1,2 This is the case with Alzheimer disease (AD), whose long duration requires us to consider not only the opinions and preferences of these patients but also those of caregivers, who bear a significant burden.3,4

HRQoL is an abstract, subjective, culture-dependent and multidimensional concept which considers quality of life from the point of view of health.5 The dimensions most strongly associated with HRQoL are physical, emotional, and social functioning; functional role; cognitive function; perception of general health; and well-being.6 Although HRQoL was originally linked to physical functioning, increasing emphasis has been placed in recent years on the subjective and emotional aspects of health; in fact, HRQoL is sometimes used as a synonym for perceived health.7 The importance of HRQoL resides in its conception of patients as the central focus of healthcare.8

Assessing HRQoL involves evaluating the impact of a disease and its treatment on patients’ perception of their satisfaction and physical, psychological, social, and spiritual well-being. Measuring HRQoL is necessary for delivering objective, comparable results. HRQoL provides data on patients’ perceived health states and constitutes a patient-centred outcome measure in research studies of interventions for a number of conditions. The measure is increasingly used in clinical research studies, epidemiological studies, cost-effectiveness studies of certain interventions,2 and even as one of the main variables in clinical trials.9

Certain psychometric properties must be met to confirm the usefulness of questionnaires assessing HRQoL.10–12 In the context of AD, HRQoL may be assessed not only in patients (patient- or caregiver-reported HRQoL) but also in caregivers, who also bear a substantial burden.13 The need to assess HRQoL in caregivers of patients with AD is explained by their role as co-therapists and the risk of caregiving burden throughout the course of the disease. Presence of psychological alterations in caregivers results in faster disease progression in their patients.14,15 Furthermore, caregivers are the people who best know patients’ needs; they assume caregiving costs, and their decision to stop caring for their relatives frequently results in institutionalisation.16–18

Few studies have addressed HRQoL in caregivers of AD patients in our setting; longitudinal studies are even rarer.19,20 No significant changes in HRQoL are generally seen over the course of one year.21 The purpose of our study was to analyse the progression of HRQoL in primary caregivers (PC) of patients with AD over a 12-month period using the 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).22

Patients and methodsWe conducted a longitudinal paired-sample study including 97 patients diagnosed with AD plus their PCs (n=97).

Patients were recruited consecutively from the dementia unit of the neurology department at Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Victoria from January 2014 to May 2014. All participants were followed up for 12 months. Our study ended in May 2015. Inclusion criteria were as follows: having a diagnosis of AD according to the NINCDS-ADRDA diagnostic criteria (National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association), and displaying mild-to-moderate AD according to the Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST; stages 6c or lower). We excluded patients with other types of dementia and those at severe stages of AD (FAST stages 6d or higher). All the included patients had visited the neurology department at our hospital on at least 2 occasions and were receiving symptomatic treatment for AD. All patients had an identifiable PC. We excluded patients living in geriatric residences and those patients or caregivers who may have been unable to undergo follow-up assessments in the following 12 months.

All PCs were informed verbally and in writing about the study and signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the province of Málaga and complies with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patients and caregivers meeting all the inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria were included in the study after visiting the dementia unit.

Patients’ and caregivers’ sociodemographic characteristics were recorded at the baseline visit. We also recorded data on patients’ clinical and care-related variables. All these variables were gathered from interviews and from patients’ medical histories. Additionally, all PCs completed the SF-36 survey. The questionnaire was self-administered in most cases; in some cases, however, it had to be administered by a third party due to issues with sight or literacy. All PCs completed the same survey a second time at 12 months during consultation at the dementia unit.

SF-36 is a generic questionnaire consisting of 36 items grouped into 8 dimensions providing information on physical functioning (PF), physical role (PR), bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), vitality (VT), social functioning (SF), emotional role (ER), and mental health (MH).23–25 This questionnaire is not designed to generate a global index; however, physical and mental health summary scores have been proposed as indicators of physical and mental health. For each item, responses are scored 0 (worst health state for that item) to 100 (best health state for that item). The mean score of all items in each dimension is calculated to give a dimension global score. For each item, the distance between contiguous categories is assumed always to be the same. Furthermore, each item in each of the 8 dimensions has the same weight on the global score of that dimension.26

Data were recorded in a notebook with an identifying code. All data were masked and analysed using SPSS statistical software version 20.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of patients’ and caregivers’ sociodemographic, clinical, and caregiving variables. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute and relative frequencies and continuous variables as means±SD and minimum and maximum values, with a 95% confidence interval.

We recorded scores on each of the 8 dimensions of the SF-36 survey at baseline and at 12 months and compared them using the paired samples t test with a significance level of α=0.05 and assuming BP and SF to be the SF-36 dimensions which would require the greatest number of participants in order to detect any differences.27,28

ResultsOur sample included 97 patient-PC dyads; 11 PCs were lost to follow-up (11.34%) and 86 PCs were assessed at 12 months. Losses to follow-up were due to death (n=5), institutionalisation (n=3), failure to attend several medical appointments and/or telephone calls (n=2), and admission to hospital (n=1).

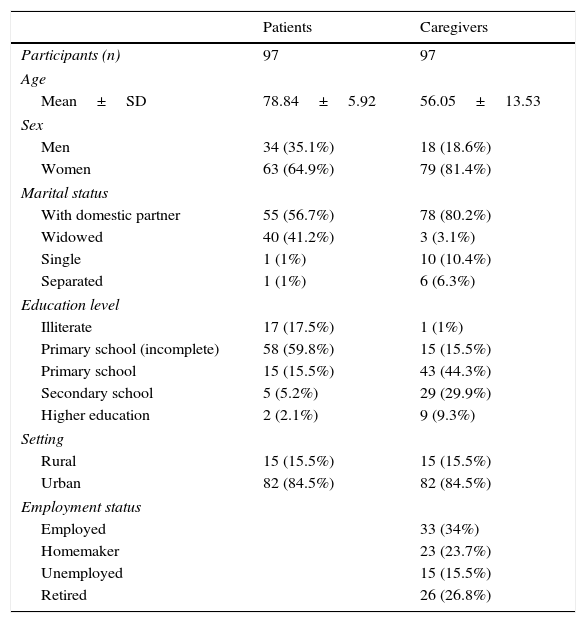

Mean age of our patients was 78.84 years (range, 62–89); 64.9% were women. Patients lived with their partners or were widowed; other marital statuses were rare. Around 77.3% of patients had not completed primary school. Most patients came from urban environments (84.5%) (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of patients and primary caregivers.

| Patients | Caregivers | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 97 | 97 |

| Age | ||

| Mean±SD | 78.84±5.92 | 56.05±13.53 |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 34 (35.1%) | 18 (18.6%) |

| Women | 63 (64.9%) | 79 (81.4%) |

| Marital status | ||

| With domestic partner | 55 (56.7%) | 78 (80.2%) |

| Widowed | 40 (41.2%) | 3 (3.1%) |

| Single | 1 (1%) | 10 (10.4%) |

| Separated | 1 (1%) | 6 (6.3%) |

| Education level | ||

| Illiterate | 17 (17.5%) | 1 (1%) |

| Primary school (incomplete) | 58 (59.8%) | 15 (15.5%) |

| Primary school | 15 (15.5%) | 43 (44.3%) |

| Secondary school | 5 (5.2%) | 29 (29.9%) |

| Higher education | 2 (2.1%) | 9 (9.3%) |

| Setting | ||

| Rural | 15 (15.5%) | 15 (15.5%) |

| Urban | 82 (84.5%) | 82 (84.5%) |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 33 (34%) | |

| Homemaker | 23 (23.7%) | |

| Unemployed | 15 (15.5%) | |

| Retired | 26 (26.8%) | |

SD: standard deviation; n: sample size.

PCs had a mean age of 56.05 years (range, 26–87). PCs were classified according to whether or not they were the same age as their patients; mean age was 72.9 years in the first group and 48.9 in the second. Of all PCs, 81.4% were women. Most PCs lived with their partners (80.2%). Only 16.5% of PCs (n=16) had not completed primary education; these PCs were the same age as their patients. Employment status varied greatly; most PCs were active workers (34%), but 15.5% were unemployed. Nearly half of all non-coetaneous PCs were active workers (Table 1).

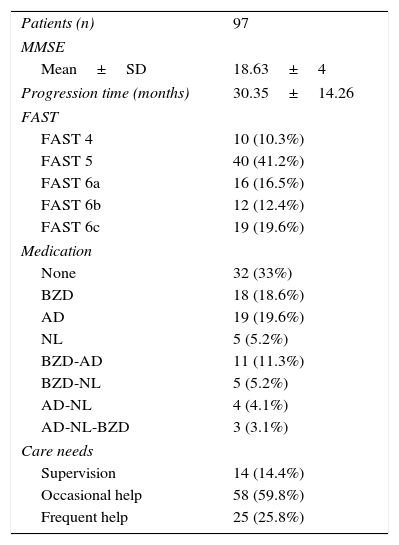

Caregiver-reported time of dementia progression from symptom onset was 2 years and a half (30.35 months). The mean MMSE score was 18.63 points; most patients required help only occasionally (patients with severe AD were not included in the study). Thirty-three percent of the patients were not receiving psychoactive drugs and 38.2% were being treated with benzodiazepines alone or in combination with another psychoactive drug (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics of our patient sample.

| Patients (n) | 97 |

| MMSE | |

| Mean±SD | 18.63±4 |

| Progression time (months) | 30.35±14.26 |

| FAST | |

| FAST 4 | 10 (10.3%) |

| FAST 5 | 40 (41.2%) |

| FAST 6a | 16 (16.5%) |

| FAST 6b | 12 (12.4%) |

| FAST 6c | 19 (19.6%) |

| Medication | |

| None | 32 (33%) |

| BZD | 18 (18.6%) |

| AD | 19 (19.6%) |

| NL | 5 (5.2%) |

| BZD-AD | 11 (11.3%) |

| BZD-NL | 5 (5.2%) |

| AD-NL | 4 (4.1%) |

| AD-NL-BZD | 3 (3.1%) |

| Care needs | |

| Supervision | 14 (14.4%) |

| Occasional help | 58 (59.8%) |

| Frequent help | 25 (25.8%) |

AD: antidepressants; BZD: benzodiazepines; SD: standard deviation; FAST: Functional Assessment Staging Test; n: sample size; MMSE: Mini–Mental State Examination; NL: neuroleptics.

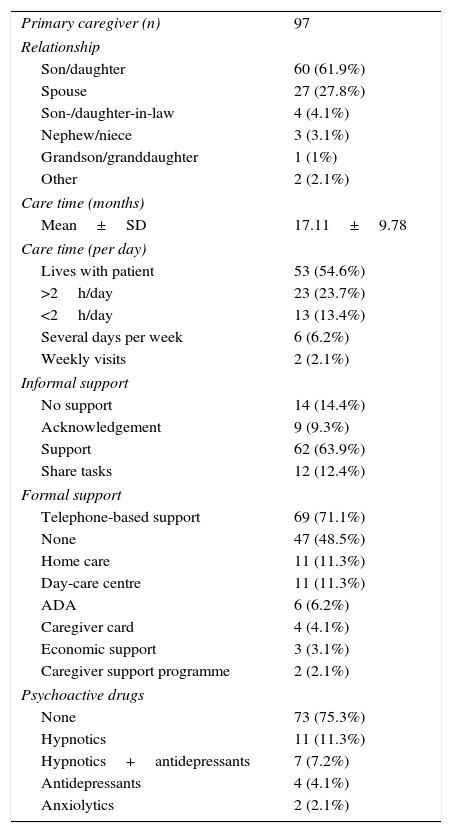

Caregiver-reported mean time of informal care was nearly one year and a half (17.11 months). Most PCs were patients’ sons/daughters (61.9%) or spouses (27.8%). In the group of non-coetaneous PCs, 4 were children-in-law, 3 were nephews/nieces, and one was a grand-daughter. The group of coetaneous PCs included one sister and one friend. Most PCs were women: 86.7% of children and 70.4% of spouses. The patient's sex also determined their relationship with the PC: male patients were usually cared for by their wives and female patients by their children. Over half of PCs (54.6%) lived with their patients. Patients whose PCs lived with them received significantly more drugs. Around 73.2% of PCs felt acknowledged or were helped by their relatives. Task sharing was reported in 12 cases; only 2 of these patients rotated between relatives’ homes (Table 3).

Variables related to patient care.

| Primary caregiver (n) | 97 |

| Relationship | |

| Son/daughter | 60 (61.9%) |

| Spouse | 27 (27.8%) |

| Son-/daughter-in-law | 4 (4.1%) |

| Nephew/niece | 3 (3.1%) |

| Grandson/granddaughter | 1 (1%) |

| Other | 2 (2.1%) |

| Care time (months) | |

| Mean±SD | 17.11±9.78 |

| Care time (per day) | |

| Lives with patient | 53 (54.6%) |

| >2h/day | 23 (23.7%) |

| <2h/day | 13 (13.4%) |

| Several days per week | 6 (6.2%) |

| Weekly visits | 2 (2.1%) |

| Informal support | |

| No support | 14 (14.4%) |

| Acknowledgement | 9 (9.3%) |

| Support | 62 (63.9%) |

| Share tasks | 12 (12.4%) |

| Formal support | |

| Telephone-based support | 69 (71.1%) |

| None | 47 (48.5%) |

| Home care | 11 (11.3%) |

| Day-care centre | 11 (11.3%) |

| ADA | 6 (6.2%) |

| Caregiver card | 4 (4.1%) |

| Economic support | 3 (3.1%) |

| Caregiver support programme | 2 (2.1%) |

| Psychoactive drugs | |

| None | 73 (75.3%) |

| Hypnotics | 11 (11.3%) |

| Hypnotics+antidepressants | 7 (7.2%) |

| Antidepressants | 4 (4.1%) |

| Anxiolytics | 2 (2.1%) |

ADA: Alzheimer disease association; SD: standard deviation.

Formal support reported by PCs at baseline was mainly telephone-based support (51.5%) and, to a much lesser extent, day-care centres and home care (11.3% in both cases). Nearly half of the patient-PC dyads (48.5%) received no external support (whether economic or through services). Of all PCs, 6.2% had contacted an AD association and 2.1% had participated in a caregiver support programme. In our sample, there were 87 instances of formal support, corresponding to a mean of 0.9 formal support actions per patient-PC dyad. However, formal care was actually provided to 50 dyads (mean of 1.74 formal support actions per dyad receiving formal care). Of all PCs, 75.3% were not taking any psychoactive drugs; the most frequently used were hypnotics (18.5%), either alone or in combination with antidepressants.

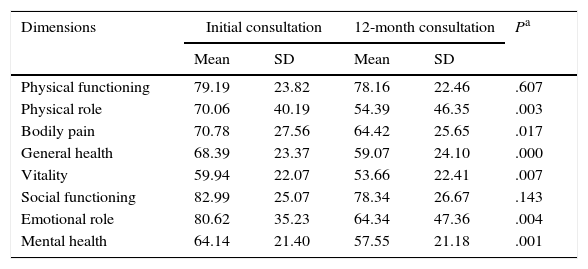

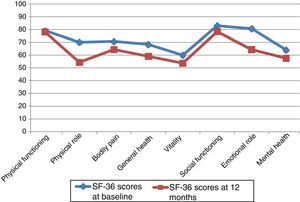

At 12 months, the SF-36 survey was completed by 86 PCs; 11 PCs were lost to follow-up. The dimensions with the highest scores, both at baseline and at 12 months, were PF and SF. The lowest scores corresponded to MH and VT. The most pronounced drops at 12 months affected PR and ER, although in both cases standard deviations nearly doubled those of the other dimensions. The 2 remaining dimensions, BP and GH, had intermediate scores (Table 4).

SF-36 scores at baseline and at 12 months.

| Dimensions | Initial consultation | 12-month consultation | Pa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Physical functioning | 79.19 | 23.82 | 78.16 | 22.46 | .607 |

| Physical role | 70.06 | 40.19 | 54.39 | 46.35 | .003 |

| Bodily pain | 70.78 | 27.56 | 64.42 | 25.65 | .017 |

| General health | 68.39 | 23.37 | 59.07 | 24.10 | .000 |

| Vitality | 59.94 | 22.07 | 53.66 | 22.41 | .007 |

| Social functioning | 82.99 | 25.07 | 78.34 | 26.67 | .143 |

| Emotional role | 80.62 | 35.23 | 64.34 | 47.36 | .004 |

| Mental health | 64.14 | 21.40 | 57.55 | 21.18 | .001 |

SD: standard deviation.

Neither PF nor SF displayed significant differences between baseline and 12-month follow-up scores, although they did worsen throughout the study period. Scores worsened significantly in the remaining 6 dimensions, with a significance level of P<.05, or P≤.001 in the case of MH and GH. Fig. 1 displays baseline and 12-month follow-up scores for the 8 dimensions. The subgroups of PCs who were women or sons/daughters scored significantly lower in all 8 dimensions except for PF and SF. However, the subgroup of sons/daughters scored higher on PF and BP than the general group of PCs.

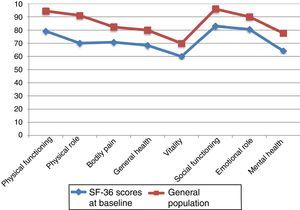

Fig. 2 compares baseline scores on the 8 dimensions in our sample and in the general population, adjusted for age and sex.29,30 We observed differences greater than 10 points in all 8 dimensions; in all cases, scores were lower in our sample of PCs than in the general population. Both groups displayed the highest scores in PF and SF and the lowest scores in VT.

DiscussionOur results show a worsening in the HRQoL of caregivers of patients with AD. Our sample was reasonably homogeneous in terms of dementia aetiology (all patients were diagnosed with AD after several consultations); patients with severe AD were excluded. These characteristics, in addition to the paired-sample design of our study, minimise the risk of selection bias (participants were not randomly selected).

Although our study was conducted in the hospital setting, we feel that our sample is representative of the general population in our health district, given that healthcare is universal in our setting and that the slowly progressive course of AD requires specialised treatment.

Only 11.34% of PCs were lost to follow-up, a rather low rate for a study of AD treatment; these studies usually report considerably higher drop-out rates in the control group and even in the patient group.31

SF-36 is a widely used tool for measuring HRQoL; it has been validated in Spain and previous studies have confirmed its validity and reliability.32 It is a generic scale, enabling us to compare results.

Our patients’ sociodemographic characteristics are similar to those seen in other studies.30,33–35 Regarding caregivers’ education level, a high percentage of non-coetaneous PCs were literate. The rate of psychoactive drug use in our sample (67%) is similar to that reported by Olazarán et al.36 in a large sample of patients living in geriatric residences.

Identifying the PC at baseline was not easy in some cases, especially when patients were men and were cared for both by their wives and by their daughters. In these cases, daughters indicated which one of the 2 relatives was most involved in caregiving; in general terms, wives were usually responsible for the patient in the initial stages of AD whereas daughters cared for the patients in more advanced stages of the disease. However, being identified as PC should not result in stigmatisation or increased burden for caregivers; rather, it provides information on the patients’ family setting and informal care (secondary caregivers, absent caregivers). In our sample, only 2 patients rotated between relatives’ homes (sons and daughters); other studies in our setting report a considerably higher rotation rate.35,37 This may partially be explained by the fact that elderly patients usually own their homes whereas non-coetaneous caregivers have been affected by the economic crisis.

The percentage of female PCs was slightly higher in our sample than in other studies,19,31,33,38–43 unlike in most countries in northern Europe and the United States, where the proportions of male and female PCs are more balanced. In our study, the percentage of PCs who lived with the patient was lower than those reported in other studies conducted in our setting.19,40

In our sample, PCs were mostly daughters in their fifth or sixth decade of life who lived with their partners and had completed at least their primary education.

Very few PCs in our sample received formal support; this finding, however, is in line with the results of a study conducted in Germany.44 In the context of the law for dependent people in our region, we should highlight the limited economic resources allocated to the families of dependent people (only 36.50%). Surprisingly, both in our sample and in the general population of Andalusia, the aforementioned law does not allocate any resources either to preventing dependence and promoting personal autonomy or to economic assistance for personal support (according to data from the Spanish institute for social services and the elderly [IMSERSO] from June 2015). The services and economic resources noted in other studies are variable and heterogeneous; this may partially be explained by the origin of the sample.

Scores did not decrease as markedly in PF and SF as in the rest of dimensions. In the case of PF, this may be explained by the moderate correlation between physical functioning and caregiving/caregiving burden. In the case of SF, this is more difficult to explain clinically; however, from a statistical viewpoint, SF is the dimension with the lowest internal consistency (Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.45).45 Likewise, the marked decrease in the scores of both roles (PR and ER) should be interpreted with caution, given that these 2 dimensions include few levels (4 in ER and 5 in PR), resulting in a rather discrete distribution with large standard deviations in both cases.28 As in other studies (Yıkılkan et al.46), the lowest scores correspond to ER, PR, and VT.

Baseline and 12-month follow-up scores for the 8 SF-36 dimensions are similar to those reported by Molinuevo and Hernández,33 although differences are not significant for any of the dimensions. Our study reports better scores on all dimensions than the study by Molinuevo and Hernández, which may be attributed to the fact that all patients in that study were non-responders to specific symptomatic treatment for AD. In the study conducted by Martín-Carrasco et al.20, 115 caregivers participated in a 4-month moderate-intensity psychoeducational intervention programme. At 10 months, their scores improved in all dimensions. Baseline scores were very low, however; this may partially be explained by the fact that the included caregivers performed caregiving activities for at least 4 hours per day. The fact that spouses and women scored higher on SF may be explained by the expectations these groups have about caring for their family members.

Our study provides data about HRQoL in PCs of patients with AD in our healthcare district; our results may be extrapolated to areas that are similar in terms of sociocultural characteristics and local development. Furthermore, HRQoL may serve as an outcome measure in intervention studies, helping physicians and healthcare administrators choose the most appropriate treatment strategy for each patient.

FundingThe authors have received no funding for this research study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Garzón-Maldonado FJ, Gutiérrez-Bedmar M, García-Casares N, Pérez-Errázquin F, Gallardo-Tur A, Martínez-Valle Torres MD. Calidad de vida relacionada con la salud en cuidadores de pacientes con enfermedad de Alzheimer. Neurología. 2017;32:508–515.

Part of this study was presented at the SEN's Annual Meeting in November 2014.