Epilepsy is especially prevalent in developing countries: incidence and prevalence rates are at least twice as high as in our setting. Epilepsy is also highly stigmatised, and few resources are available for its management.

Material and methodsWe performed a descriptive observational study in December 2016, distributing a questionnaire on epilepsy management to healthcare professionals from 3 different hospitals in Cameroon. Data are presented as means or percentages.

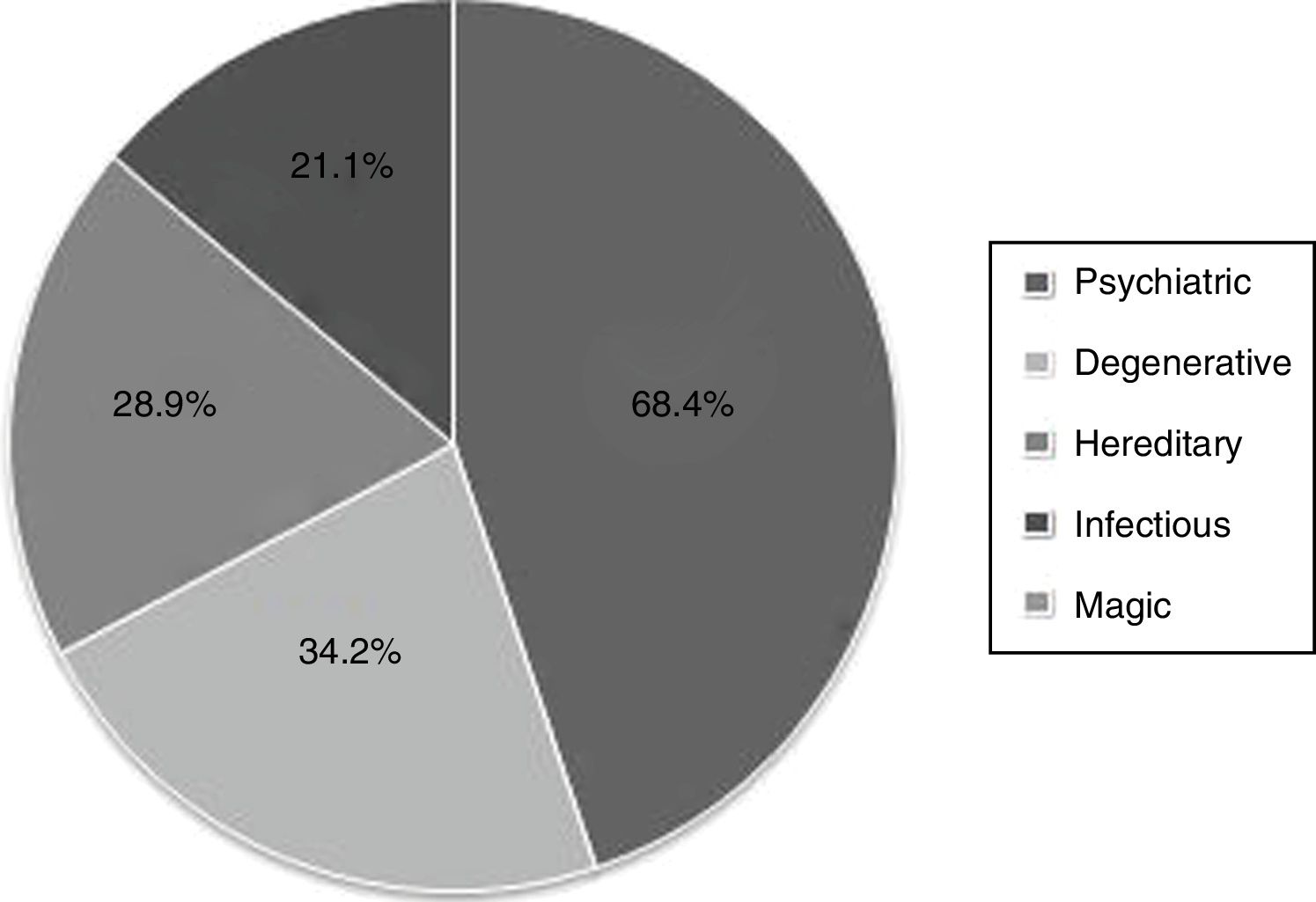

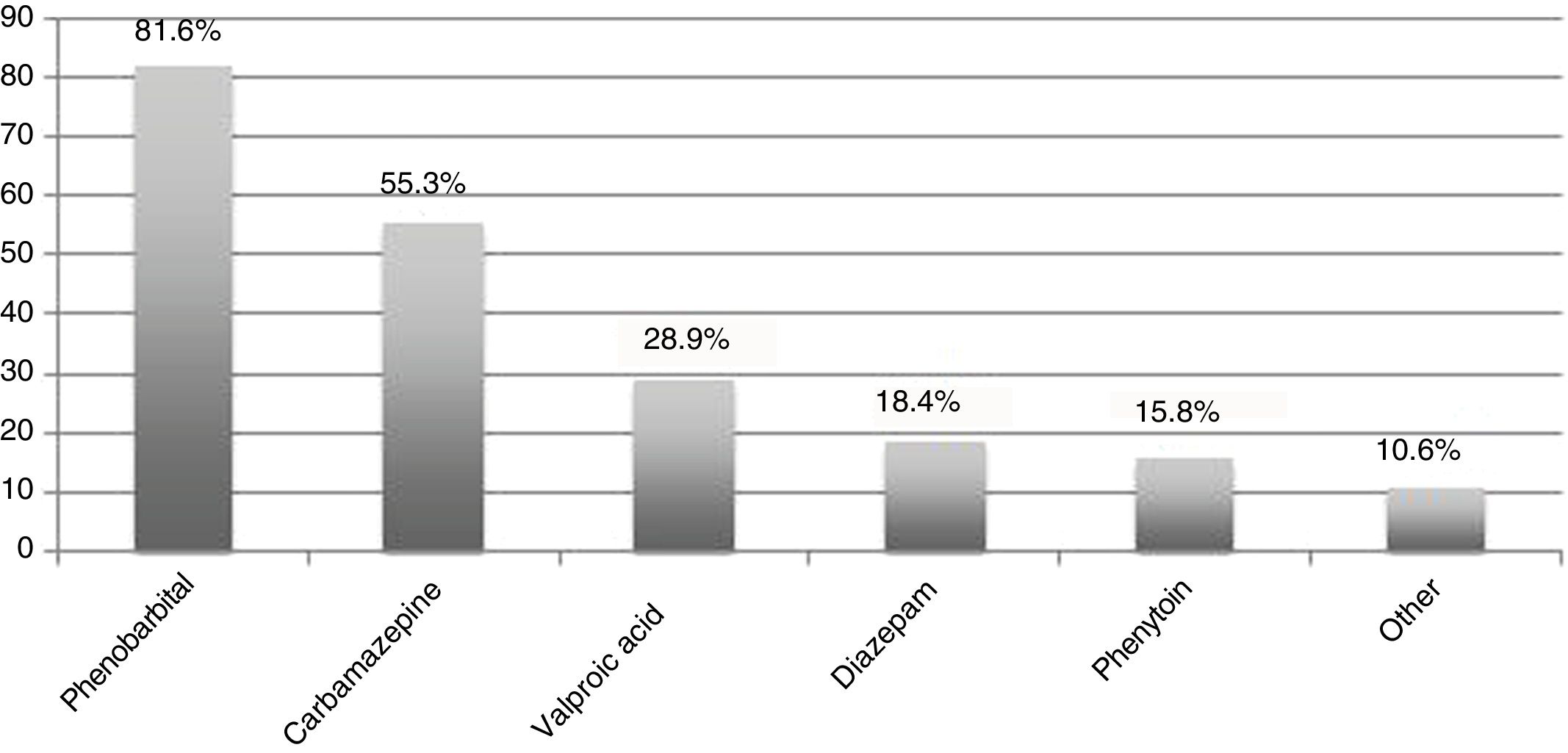

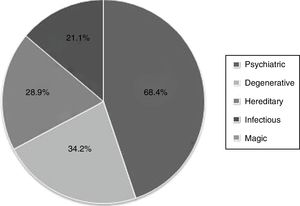

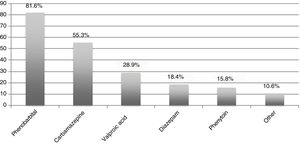

ResultsThirty-eight healthcare providers participated in the survey; 42.1% were female and mean age was 40.1 years (range, 22-62). Regarding the causes of epilepsy, 68.4% considered it a psychiatric condition, 34.2% a degenerative disease, 28.9% a hereditary condition, and 21.1% secondary to infection. In terms of management, 23.7% considered that thorough clinical history is sufficient to establish a diagnosis. Only 60.5% considered the clinical interview to be important for diagnosis, 52.6% considered EEG to be necessary, and 28.9% considered laboratory analyses to be important. Only 13.2% mentioned neuroimaging. In the treatment of pregnant women, 36.8% recommended folic acid supplementation, 65.8% believed antiepileptic treatment should be maintained, and only 39.5% recommended breastfeeding. Concerning treatment, the participants knew a mean of 2 antiepileptic drugs: phenobarbital was the best known (81.6%), followed by carbamazepine (55.3%) and valproic acid (28.9%).

ConclusionsThere is a need among healthcare professionals for education and information on the disease, its diagnosis, and management options, in order to optimise management and consequently improve patients’ quality of life.

La epilepsia es una enfermedad prevalente en países en vías de desarrollo debido al mayor número de causas que pueden producirla, al menos duplicándose tanto incidencia como prevalencia en comparación con nuestro medio. Además, existe una gran estigmatización y los medios para su manejo son limitados.

Material y métodosEstudio observacional descriptivo mediante la realización de un cuestionario a profesionales sanitarios de 3 hospitales de Camerún, interrogando sobre factores relacionados con el manejo de la epilepsia, en diciembre de 2016. Se presentan los datos como media o porcentaje.

ResultadosParticiparon 38 profesionales sanitarios, de los cuales 42,1% eran mujeres, con una edad media de 40,1 años (rango 22-62). Respecto a la causa de la enfermedad, un 68,4% la considera psiquiátrica, 34,2% degenerativa, 28,9% hereditaria y 21,1% secundaria a una infección. En cuanto al manejo, un 23,7% consideraba suficiente la anamnesis para llegar al diagnóstico. Sólo un 60,5% consideraba la historia importante en el diagnóstico, 52,6% consideraba necesario un EEG, un 28,9% creía importantes las pruebas de laboratorio y un 13,2% la neuroimagen. Durante el embarazo, sólo un 36,8% considera importante asociar ácido fólico, sólo el 65,8% cree que hay que mantener el tratamiento y sólo un 39,5% creía recomendable la lactancia. Acerca del conocimiento de antiepilépticos, el número medio de fármacos conocido era de 2, siendo el más conocido el fenobarbital (81,6%) seguido de carbamacepina (55,3%) y ácido valproico (28,9%).

ConclusionesLa educación y la mejor información sobre la enfermedad, su diagnóstico y las opciones de manejo son necesarias en los profesionales sanitarios para optimizar el manejo y con ello la calidad de vida de los pacientes.

Epilepsy is well known across the world and throughout history, with some written descriptions dating from 4000 BCE.1 According to World Health Organization reports, approximately 50 million people worldwide have the disease, with 80%-90% of these living in developing countries.2 A recent meta-analysis estimated the global prevalence of epilepsy in Sub-Saharan Africa at 9.39 cases/1000 population, with a median rate of 14.2 cases/1000 population,3 clearly higher than estimates for more developed countries. In Spain, for example, the 2015 EPIBERIA study estimated prevalence at 5.76 cases/1000 population. Incidence is estimated at 81.7 cases/100 000 person-years in developing countries and 45.0 cases/100 000 person-years in developed countries.3

Despite methodological differences, the available studies into epilepsy indicate that Cameroon is one of the countries with the highest prevalence rates, with an estimated 58.42 cases/1000 population.3,4 These differences may be explained by increased risk of infections affecting the nervous system, such as malaria, meningitis, or neurocysticercosis; higher prevalence of head trauma or perinatal complications; and reduced access to medical care. Several studies report higher prevalence in endemic areas for onchocerciasis (“river blindness”),5,6 with epilepsy prevalence increasing by 0.4% for every 10% increase in the prevalence of this disease.7 Information on epilepsy in these countries is often lacking, despite the high prevalence of the condition. Cameroon is a Central African country with a population of 23 439 189, with the majority of the population working in the agricultural sector. Various studies performed as part of the National Epilepsy Control Programme have analysed views of epilepsy in the general population and among healthcare professionals8–17; while most interviewees were aware of the disease (ils qui tombent), many had misconceptions about it, attributing it to curses or considering it to be communicable or hereditary. This gives rise to stigma about the disease, which has a considerable negative impact for patients, who have difficulties with social integration and even accessing healthcare.18–21

This study aims to assess the understanding of epilepsy in a group of healthcare professionals in Cameroon in order to identify the main areas of improvement for future training programmes.

Material and methodsWe conducted a cross-sectional, observational, descriptive study. In December 2016, 2 neurologists and an internist visited several healthcare centres in Cameroon as part of an international cooperation project run by the Recover Foundation. A written questionnaire was administered on an anonymous basis to all healthcare staff at 3 centres in the west of the country, in Batcham, Dschang, and Semto. We collected demographic data (age, sex), care-related data (number of patients with epilepsy attended per week), and clinical data (causes of epilepsy, diagnostic approach, therapeutic management with known drugs, management of pregnant patients, causes of seizures, and issues related to social stigma). Data are presented as percentages or as median and range. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software (version 20.0); the chi-square test was used to analyse associations between qualitative variables. All healthcare centres and staff gave their explicit consent to participate in the study.

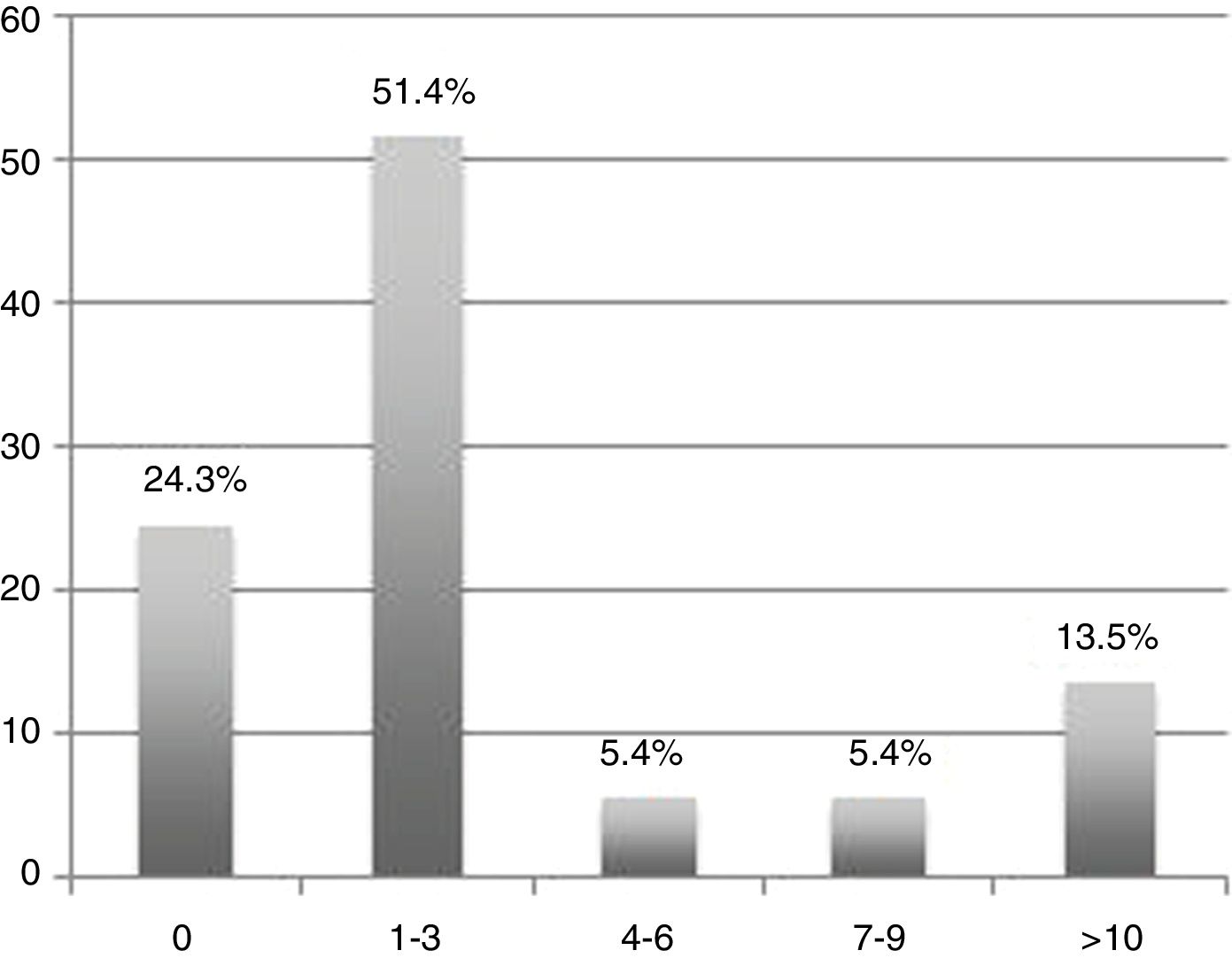

ResultsA total of 38 healthcare professionals participated, 42.1% of whom were women. Median age was 40.5 years (range, 22-62). Most participants (75.7%) attended patients with epilepsy every week, with some seeing as many as 10 patients per week (Fig. 1).

No respondent attributed the aetiology of the disease to curses or magic, although 68.4% considered it to be a psychiatric condition, followed by (in descending order of frequency) degenerative, hereditary, and infectious causes (Fig. 2). Only 23.7% of participants considered medical history to be sufficient to establish a diagnosis of epilepsy. This belief was more frequent among participants who attended more patients with epilepsy (P=.05). Regarding the tests considered necessary or useful for diagnosis, only 60.5% considered medical history to be important, 52.6% considered electroencephalography studies to be necessary, 28.9% considered laboratory studies important, and 13.2% considered neuroimaging studies to be necessary.

In terms of treatment, 86.8% of participants thought it possible to live a normal life with proper treatment, 5.3% believed no efficacious treatment existed, and 5.3% believed that medication is never sufficient to control the disease. Participants named a mean of 2.08 antiepileptic drugs (median, 2; range, 0–6). A total of 13.2% of participants could name none of these drugs, and 7.9% mentioned drugs with no anticonvulsant properties. Fig. 3 shows the most commonly mentioned drugs; the best known was phenobarbital, which was mentioned by 81.6% of participants. Regarding epilepsy management during pregnancy, only 36.8% considered it important to add folic acid to the patient’s treatment schedule, 65.8% said antiepileptic treatment should be maintained, and only 39.5% considered breastfeeding to be advisable. Regarding possible seizure trigger factors, 94.7% of participants mentioned missed doses of antiepileptic drugs, 44.7% mentioned alcohol consumption, 28.9% considered sleep alterations to be a trigger factor, and 23.7% mentioned stress as a possible cause. With respect to the management of seizures, 68.4% of participants considered it important to place the patient in the lateral decubitus position, 63.2% said the head should be protected, 39.4% said the mouth should be examined after a seizure, 13.2% thought it was important to restrain the patient, and 7.9% said fingers should be placed in the patient’s mouth to prevent asphyxia due to swallowing the tongue.

DiscussionWhile healthcare professionals at the centres where the study was conducted frequently attend patients with epilepsy, our findings suggest that there remain significant areas for improvement in the management of these patients. Regarding aetiology, we found a lower prevalence of magical beliefs about epilepsy than reported in other studies of the general population8,9,12,13 or healthcare professionals,10,15,16 although a large majority of participants considered it to be a psychiatric condition, and almost one-third believed it was hereditary.

Regarding diagnosis, our findings suggest that, despite the limited resources available, most respondents considered complementary testing to be fundamental in diagnosing epilepsy, and placed less weight on the importance of medical history interviews as the main tool. The current International League Against Epilepsy criteria consider medical history to be sufficient for the diagnosis of epilepsy.22 Although EEG presents poor sensitivity, our survey respondents attributed high negative predictive value to the technique, and considered it highly important in the diagnosis of epilepsy, despite limited access to complementary tests due to questions of availability and economic resources. One striking finding was the low mean number of drugs that respondents were able to name, with phenobarbital being the most used in daily practice, despite the relatively good availability of such other antiepileptic drugs as phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproic acid, and some benzodiazepines. None of the participants mentioned lamotrigine, which is unavailable in Cameroon despite being included on the World Health Organization’s list of essential medicines. A particularly interesting issue is the management of epilepsy in pregnant patients. Given the high birth rate in Cameroon (36.84%, vs 8.8% in Spain), proper management of these patients is of great importance. We observed a lack of knowledge on how to proceed with these patients: many participants advocated the complete suspension of treatment, which may give rise to significant risks to both mother and baby. Some participants also advised against breastfeeding, which is an important source of nutrition in the first months of life, especially in countries with limited resources. Furthermore, the poor variety of treatments available forces physicians to use potentially teratogenic drugs, hence the vital importance of prescribing folic acid. The limitations of the study include the fact that we did not specifically evaluate the participants’ level of education, and took into account the number of patients habitually attended. We only surveyed staff from 3 centres in Cameroon; the sample therefore may not be representative of other regions of the country or continent.

ConclusionsWhile epilepsy is common in everyday clinical practice in Cameroon, understanding of the disease is limited; this is especially true of its diagnosis and management, particularly in pregnant patients. In the light of our findings, we consider that training on epilepsy for healthcare staff could substantially improve the situation of these patients, without requiring excessive resources.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: C. Delgado-Suárez, García-Azorín D, Monje MHG, Molina-Sánchez M, Gómez Iglesias P, Kurtis MM, et al. Identificando puntos de mejoría en el manejo de la epilepsia en países en vías de desarrollo: experiencia de neurocooperación en Camerún. Neurología. 2021;36:29–33.

Part of this study was presented as an oral communication at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Spanish Society of Neurology, Valencia, November 2017.