To describe non-relapse-related emergency consultations of patients with multiple sclerosis (MS): causes, difficulties in the diagnosis, clinical characteristics, and treatments administered.

MethodsWe performed a retrospective study of patients who attended a multiple sclerosis day hospital due to suspected relapse and received an alternative diagnosis, over a 2-year period. Demographic data, clinical characteristics, final diagnosis, and treatments administered were evaluated. Patients who were initially diagnosed with pseudo-relapse and ultimately diagnosed with true relapse were evaluated specifically. As an exploratory analysis, patients who consulted with non-inflammatory causes were compared with a randomly selected cohort of patients with true relapses who attended the centre in the same period.

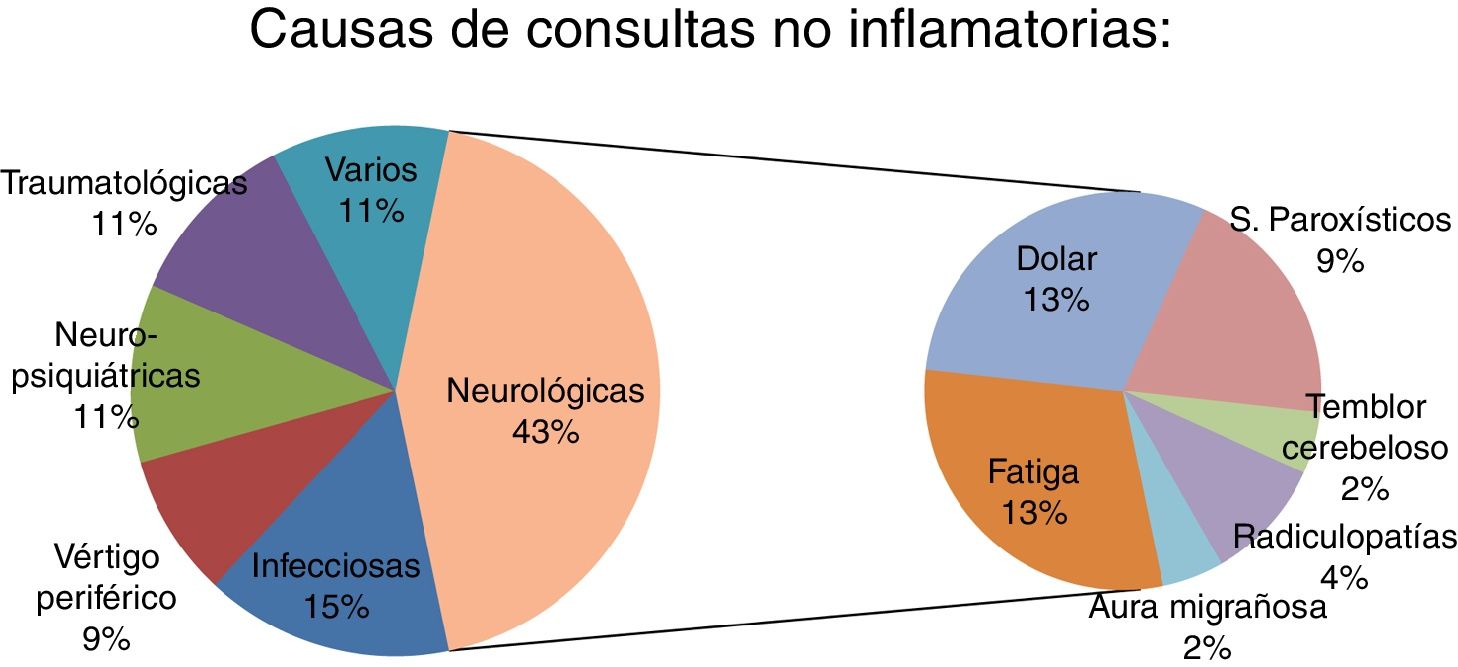

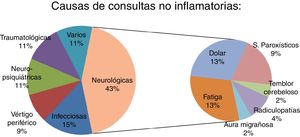

ResultsThe study included 50 patients (33 were women; mean age 41.4 ± 11.7 years). Four patients (8%) were initially diagnosed with pseudo-relapse and later diagnosed as having a true relapse. Fever and vertigo were the main confounding factors. The non-inflammatory causes of emergency consultation were: neurological, 43.5% (20 patients); infectious, 15.2% (7); psychiatric, 10.9% (5); vertigo, 8.6% (4); trauma, 10.9% (5); and miscellaneous, 10.9% (5).

ConclusionsMS-related symptoms constituted the most frequent cause of non-inflammatory emergency consultations. Close follow-up of relapse and pseudo-relapse is necessary to detect incorrect initial diagnoses, avoid unnecessary treatments, and relieve patients’ symptoms.

Describir consultas urgentes de pacientes con esclerosis múltiple (EM) distintas a brotes: causas, dificultades diagnósticas, características clínicas y tratamientos empleados.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de los pacientes que acudieron a un Hospital de Día de EM en 2 años por sospecha de brote y que recibieron un diagnóstico alternativo. Se evaluaron variables demográficas, características clínicas de los pacientes, diagnósticos finales y tratamientos. Los pacientes con diagnóstico final de brote e inicialmente diagnosticados de pseudobrote se evaluaron específicamente. Con una finalidad exploratoria se compararon las características de los pacientes que consultaban por causas no inflamatorias con una cohort de pacientes aleatoriamente seleccionados que habían sufrido un brote en el mismo periodo de tiempo.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 50 pacientes inicialmente diagnosticados de pseudobrotes (33 mujeres, con edad media 41,4 ± 11,7 años). Cuatro pacientes (8% del total) fueron inicialmente diagnosticados de pseudobrote aunque posteriormente fueron diagnosticados de un verdadero brote. La fiebre y el vértigo fueron los principales factores de confusión. Las causas no inflamatorias de consulta urgente fueron: neurológicas: 43,5% (20); infecciosas: 15,2% (7); psiquiátricas: 10,9% (5); vértigo: 8,6% (4); traumatológicas: 10,9% (5), y otras: 10,9% (5).

ConclusionesLa mayor parte de las consultas urgentes no inflamatorias fueron causadas por síntomas relacionados con la EM. El seguimiento estrecho de brotes y pseudobrotes es necesario para detectar diagnósticos incorrectos, evitar tratamientos innecesarios y aliviar los síntomas de los pacientes.

The therapeutic management of multiple sclerosis (MS) involves 4 very different approaches: 1) disease-modifying treatment, 2) acute treatment of relapses, 3) symptomatic treatments aimed at alleviating symptoms and sequelae of relapses and disease progression itself, and 4) rehabilitation treatment.

The McDonald criteria define relapse as a clinicopathological episode caused by inflammatory and demyelinating MS lesions that clinically progresses with acute or subacute onset of new neurological symptoms lasting more than 24 hours, or exacerbation of existing neurological symptoms that have remained stable for at least 30 days. The definition of relapse in the 2001 McDonald criteria assumes “expert clinical assessment that the event is not a pseudoattack.” Typically, increased environmental temperature, humidity, and intercurrent diseases (Uhthoff phenomenon) may cause worsening of previous symptoms unrelated to the inflammatory activity of the disease.

In many cases, differentiating between relapse and pseudorelapse is difficult. Infectious symptoms and fever occasionally precede a true relapse. Medical and psychiatric complications (related or unrelated to MS) and treatments may also mimic a relapse. Furthermore, even in the era of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), topographical diagnosis of a new MS lesion in the central nervous system is not simple, since a precise clinical and radiological correlation is not always present; therefore, diagnosis of relapse is predominantly clinical. Furthermore, it is not always possible to perform an MRI study in the acute phase and patients are occasionally attended by emergency departments at times when it is not possible to consult their usual physicians.

Treatment of MS relapses with high doses of corticosteroids is a generalised and beneficial practice for patients, although its influence on prognosis is controversial. Furthermore, not all relapses are treated with corticosteroids, and there are situations, such as infections, in which corticosteroids may potentially be harmful. We considered emergency consultations due to non-inflammatory causes (non-inflammatory causes of consultation) to be all those consultations due to acute or subacute symptom worsening not secondary to inflammatory activity of the disease. The aim of our study is to present a series of patients who initially consulted due to suspicion of relapse but received alternative diagnoses; to describe clinical symptoms, difficulties in diagnosis, and treatment; and to analyse the differences between relapses and pseudorelapses.

We hope our study will help to improve the management of acute/subacute MS symptoms in patients attended in emergency departments or directly in day hospitals and MS rapid-access clinics by providing information on issues other than relapses.

Material and methodsThis is a retrospective descriptive study including data from a 2-year period on patients with MS who required emergency consultation at an MS day hospital due to suspicion of relapse but whose definitive diagnosis was different to the initial suspicion. We also describe in detail the subgroup of patients initially diagnosed with pseudorelapse who were subsequently diagnosed with MS relapse.

We performed an exploratory comparison between patients presenting pseudorelapses and those diagnosed with relapse who were attended during the same time period. The aim of this comparative analysis is to establish clinical or demographic differences between both groups.

Definitions and variablesDiagnosis of MS was based on the 2010 McDonald criteria. Patients diagnosed with clinically isolated syndrome at the time of the relapse or pseudorelapse were subsequently diagnosed with MS. We considered MS relapse to be the acute or subacute onset of new symptoms or the exacerbation of existing symptoms, lasting longer than 24 hours, exclusively attributable to the inflammatory and demyelinating activity of MS. Symptoms were assessed by a neurologist (L.A.R.A., M.J.A.-A.P., I.P., or C.O.G.) who initially classified patients as presenting relapse or non-inflammatory symptoms. Two neurologists who had not previously assessed the patients (I.G.C. and I.G.S.) reviewed their data.

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation were defined as clinical worsening of patients with MS that could not be attributed to the inflammatory and demyelinating activity of the disease. Paroxysmal symptoms were considered pseudorelapses rather than true relapses when their frequency was equal to or less than one episode per day and/or a causal relationship could be established with known lesions according to anatomical and temporal criteria.

We analysed demographic and clinical variables. Demographic variables included age and sex; clinical variables were:

- 1

Type of MS.

- 2

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation.

- 3

Disease-modifying treatment at the time of consultation.

- 4

Disease progression time (in years) from the first symptom to the current consultation, as reported in the patient’s clinical history.

- 5

Disease progression time (in years) from diagnosis of MS to the current consultation, as reported in the patient’s clinical history.

- 6

Time to consultation (in days): from onset of relapse or pseudorelapse symptoms to the date of consultation.

- 7

Presence of anxiety, depression, or cognitive impairment: dichotomous variable (yes/no) based on the data collected from the clinical history.

- 8

Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score at the time of consultation for patients diagnosed with pseudorelapse and before the consultation in patients diagnosed with true relapse.

- 9

Number of relapses reported in the clinical history in the year prior to the current consultation.

- 10

Specific treatment of the pseudorelapse: dichotomous variable (yes/no) indicated by the neurology department.

- 11

Referral to other specialists: dichotomous variable (yes/no).

All patients had been informed by doctors and nurses from the unit about the possibility of experiencing an MS relapse or the exacerbation of MS symptoms in the context of concurrent medical processes. Patients could attend the day hospital’s MS unit freely or with an appointment and be assessed by a neurologist specialising in MS. All patients diagnosed with MS relapse or with symptoms of non-inflammatory origin were advised to contact the unit if their symptoms did not improve or if new symptoms appeared. All patients were re-assessed within 3 months. We excluded patients who did not attend follow-up assessments and those whose diagnosis was doubtful in the opinion of either of the reviewing neurologists (I.G.C. and I.G.S.). According to the judgement of the neurologists attending the patients (L.A.R.A., M.J.A.-A.P., I.P., C.O.G.), complementary examinations were performed in some patients to confirm or rule out the presence of new inflammatory activity or any concomitant condition.

Statistical analysisQualitative variables are expressed as absolute frequencies and percentages, and quantitative variables as mean with standard deviation (SD) (range), median, or mode. In the comparison between patients presenting pseudorelapse and those presenting true relapse, we considered the variables mentioned above. Qualitative variables were analysed with the chi-square test and the Fisher exact test, and quantitative variables with the t test or non-parametric tests. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05. Data were analysed using the SPSS statistical software, version 22.0 (SPSS, Inc.)

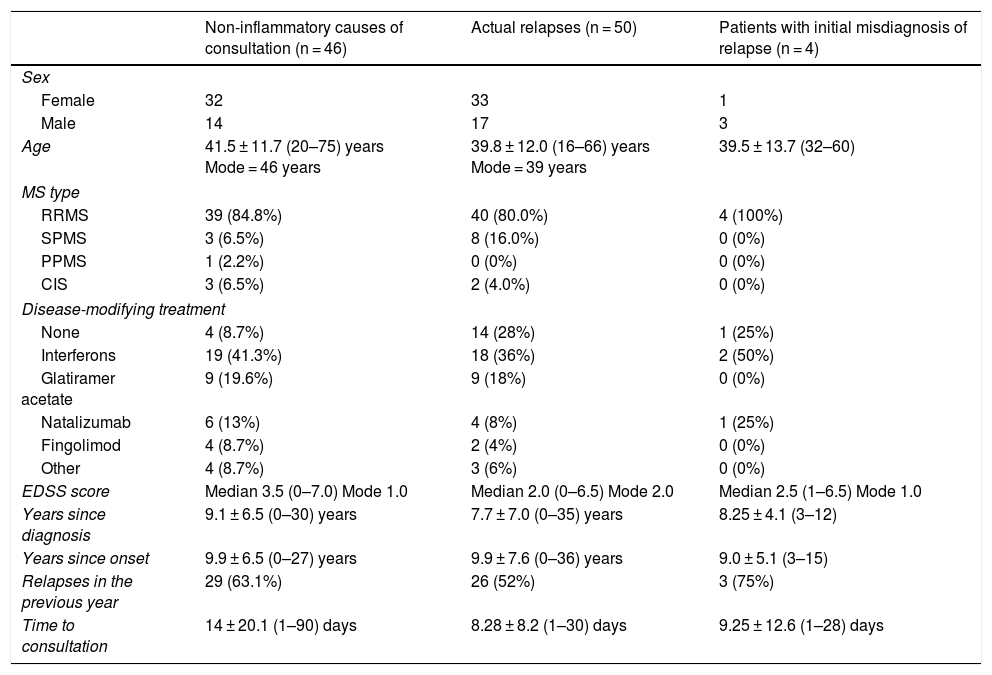

ResultsDemographic and disease data (Table 1)We initially attended 56 patients with non-inflammatory symptoms, although 6 were excluded due to the lack of follow-up (4) and doubts raised in the retrospective review of the cases (2). Therefore, we collected data from a total of 50 patients who were initially diagnosed with a non-inflammatory cause; of these, 4 were subsequently diagnosed with true MS relapse. Descriptive data of the patients consulting with non-inflammatory symptoms (n = 46), patients with relapses (n = 50), and those initially diagnosed with pseudorelapse but subsequently diagnosed with relapse (n = 4) are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in demographic variables between study groups.

Description of the study population.

| Non-inflammatory causes of consultation (n = 46) | Actual relapses (n = 50) | Patients with initial misdiagnosis of relapse (n = 4) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female | 32 | 33 | 1 |

| Male | 14 | 17 | 3 |

| Age | 41.5 ± 11.7 (20–75) years Mode = 46 years | 39.8 ± 12.0 (16–66) years Mode = 39 years | 39.5 ± 13.7 (32–60) |

| MS type | |||

| RRMS | 39 (84.8%) | 40 (80.0%) | 4 (100%) |

| SPMS | 3 (6.5%) | 8 (16.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| PPMS | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| CIS | 3 (6.5%) | 2 (4.0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Disease-modifying treatment | |||

| None | 4 (8.7%) | 14 (28%) | 1 (25%) |

| Interferons | 19 (41.3%) | 18 (36%) | 2 (50%) |

| Glatiramer acetate | 9 (19.6%) | 9 (18%) | 0 (0%) |

| Natalizumab | 6 (13%) | 4 (8%) | 1 (25%) |

| Fingolimod | 4 (8.7%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 4 (8.7%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| EDSS score | Median 3.5 (0–7.0) Mode 1.0 | Median 2.0 (0–6.5) Mode 2.0 | Median 2.5 (1–6.5) Mode 1.0 |

| Years since diagnosis | 9.1 ± 6.5 (0–30) years | 7.7 ± 7.0 (0–35) years | 8.25 ± 4.1 (3–12) |

| Years since onset | 9.9 ± 6.5 (0–27) years | 9.9 ± 7.6 (0–36) years | 9.0 ± 5.1 (3–15) |

| Relapses in the previous year | 29 (63.1%) | 26 (52%) | 3 (75%) |

| Time to consultation | 14 ± 20.1 (1–90) days | 8.28 ± 8.2 (1–30) days | 9.25 ± 12.6 (1–28) days |

CIS: clinically isolated syndrome; EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

The most frequent symptoms were fatigue (6 patients) and central neuropathic pain (6 patients), followed by paroxysmal phenomena (4 patients) and cerebellar tremor (one patient). In these 17 patients (37% of pseudorelapses), symptoms were directly caused by MS. A further 3 patients presented neurological symptoms not associated with MS: radiculopathies (2) and migraine auras (1).

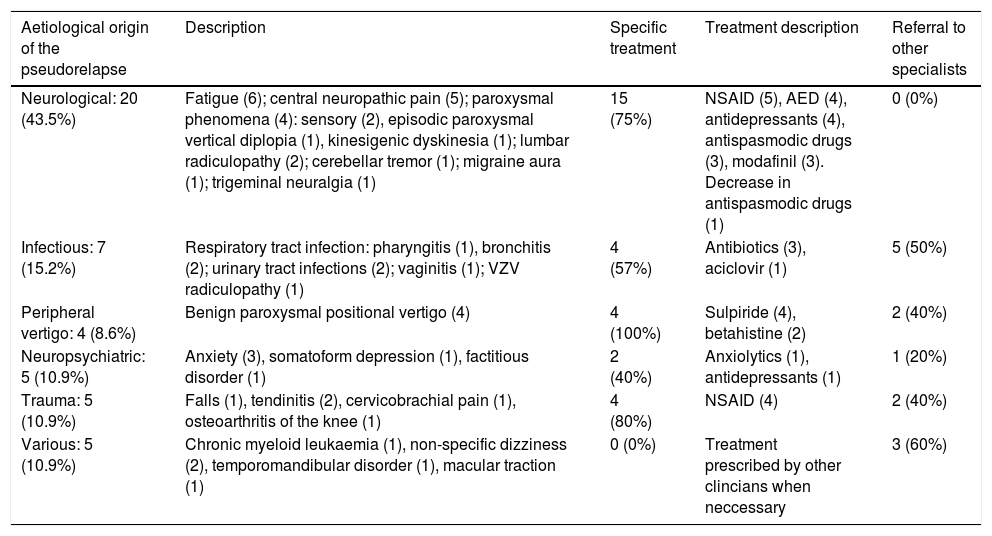

Characteristics of non-inflammatory causes of consultation.

| Aetiological origin of the pseudorelapse | Description | Specific treatment | Treatment description | Referral to other specialists |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurological: 20 (43.5%) | Fatigue (6); central neuropathic pain (5); paroxysmal phenomena (4): sensory (2), episodic paroxysmal vertical diplopia (1), kinesigenic dyskinesia (1); lumbar radiculopathy (2); cerebellar tremor (1); migraine aura (1); trigeminal neuralgia (1) | 15 (75%) | NSAID (5), AED (4), antidepressants (4), antispasmodic drugs (3), modafinil (3). Decrease in antispasmodic drugs (1) | 0 (0%) |

| Infectious: 7 (15.2%) | Respiratory tract infection: pharyngitis (1), bronchitis (2); urinary tract infections (2); vaginitis (1); VZV radiculopathy (1) | 4 (57%) | Antibiotics (3), aciclovir (1) | 5 (50%) |

| Peripheral vertigo: 4 (8.6%) | Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (4) | 4 (100%) | Sulpiride (4), betahistine (2) | 2 (40%) |

| Neuropsychiatric: 5 (10.9%) | Anxiety (3), somatoform depression (1), factitious disorder (1) | 2 (40%) | Anxiolytics (1), antidepressants (1) | 1 (20%) |

| Trauma: 5 (10.9%) | Falls (1), tendinitis (2), cervicobrachial pain (1), osteoarthritis of the knee (1) | 4 (80%) | NSAID (4) | 2 (40%) |

| Various: 5 (10.9%) | Chronic myeloid leukaemia (1), non-specific dizziness (2), temporomandibular disorder (1), macular traction (1) | 0 (0%) | Treatment prescribed by other clincians when neccessary | 3 (60%) |

AED: antiepileptic drug; NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; VZV: varicella zoster virus.

Of the patients consulting due to fatigue, only 2 had not presented relapses in the previous year. The remaining 4 had presented one relapse (2 patients) or 2 relapses (2 patients) in the previous year. Therapeutic interventions aimed at treating fatigue were introduction of treatment with antidepressants (1), reduction of treatment for spasticity (1), and introduction of treatment with modafinil (3).

Patients with pseudorelapses consisting of central pain (6) presented a range of symptoms: trigeminal neuralgia (1 patient), limb pain (3), pain in one side of the body (1), and generalised pain (1). Two patients with limb pain and the patient with hemicorporal pain had previously presented relapses affecting the painful area. We indicated analgesic treatment in all patients (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antidepressants, treatments for spasticity, and antiepileptic drugs). The patient with trigeminal neuralgia required several treatment changes to control symptoms. The patient with generalised pain presented a high EDSS score, generalised somatic pain, and significant spasticity. Half of these patients (3) had not presented relapses in the previous year, and the other half had presented one relapse.

Four patients presented paroxysmal phenomena that were not attributed to a relapse due to their low frequency. Patient 1 presented kinesigenic dyskinesia occasionally associated with exercise, and received no symptomatic treatment. Patient 2 presented episodes of binocular diplopia lasting several seconds and progressing for one week; no active lesions were detected in the MRI scan obtained during the acute phase, anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies were negative, and symptoms improved with administration of amitriptyline. Patient 3 presented occasional, painless fluctuating episodes of hypoaesthesia in the right leg and hemithorax, having experienced a severe spinal relapse 6 months before; she required no symptomatic treatment. Two months after a first episode of myelitis, patient 4 presented paroxysmal sensory symptoms that consisted of paraesthesia in the left arm, leg, and hemithorax, requiring no symptomatic treatment. Three of these patients (75%) had experienced a relapse in the previous year; it is worth mentioning that paroxysmal phenomena frequently occurred shortly after an MS relapse. This was also the case for pain onset, although in a lower percentage of cases. However, there were no statistically significant differences in the appearance of these symptoms and the presence of relapses in the previous year as compared to patients with other non-inflammatory symptoms.

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation of infectious originWe identified 7 patients with pseudorelapses of infectious origin: patient 1 presented weakness in all 4 limbs, loss of appetite, fatigue, and low-grade fever secondary to a urinary tract infection; this patient already presented severe quadriplegia due to MS. Patient 2 initially presented pain in multiple thoracic metameres, radicular pain, and a skin rash caused by herpes zoster infection (dorsal and lumbar multimetameric) while receiving treatment with azathioprine; the treatment was therefore suspended. Patient 3 had primary progressive multiple sclerosis (PPMS) and was attended due to increased difficulty walking in the context of an upper respiratory tract infection. Patient 4 was attended due to exacerbation of known ataxia and general symptoms including low-grade fever, generalised arthromyalgia, and tiredness in association with a viral infection. Patient 5 presented increased weakness in the lower limbs (she already presented paraparesis) in the context of a urinary tract infection. Patient 6 presented low-grade fever in the context of vaginitis; she reported right retro-ocular pain and transient loss of visual acuity. Patient 7 presented a respiratory tract infection that progressed with fever, coughing, and rhinorrhoea that led to an exacerbation of existing hemiparesis.

It should be noted that 5 of the 7 patients (71%, with no statistically significant differences) had presented a relapse in the previous year. Furthermore, these patients’ EDSS scores (median of 5) were considerably higher than those of the remaining patients, although no statistically significant difference was found.

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation of neuropsychiatric originA total of 5 patients consulted due to symptoms of neuropsychiatric origin. The first patient presented generalised tremor in the context of anxiety associated with existing previous postural tremor in the right arm, a sequela of her condition. A second patient reported poorer motor skills and transient paraesthesia in the right arm at specific times of high work stress. The third patient attended due to binocular vision loss lasting several seconds, associated with an anxiety attack. The fourth patient consulted due to multiple somatic symptoms (eye irritation, knee pain, constipation, chest pain), fatigue, exacerbation of motor sequelae, and depressed mood secondary to the recent discontinuation of antidepressants due to poor tolerance; treatment with another antidepressant was started, which improved mood. The fifth patient reported severe binocular loss of visual acuity of subacute onset, generalised tiredness, and headache. The examination found that symptoms caused mild functional impairment and severely impaired visual acuity (0.05). Results of an optical coherence tomography and consultation with an ophthalmologist revealed no signs of optic neuritis. Symptoms resolved spontaneously within a week. The patient had history of atypical symptoms that could not be explained by organic pathology.

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation of traumatic originFive patients consulted due to symptoms of traumatic origin: one patient due to contusions in both knees following a fall, 2 patients due to mechanical lower limb pain as a consequence of tendinitis, one patient due to cervicobrachial pain of mechanical origin, and one patient due to osteoarthritis of the knee. In all these cases, the extensive location of pain, the functional involvement of the limbs, and pain duration led the patients to request a consultation, suspecting a relapse. Four patients (80%) were treated with anti-inflammatory drugs and 2 (40%) were referred to the traumatology department.

Non-inflammatory causes of consultation of vestibular originFour patients presented benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. All patients were prescribed specific treatment with sulpiride (4) or betahistine (2). Patients diagnosed with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo had presented fewer relapses in the previous years (only one patient, 25%) than other patients, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Other non-inflammatory causes of consultationFour patients received other diagnoses as the origin of their non-inflammatory symptoms. Patient 1 presented pain and decreased visual acuity of subacute onset in the right eye. She reported that pain was mild, describing it as a feeling of heaviness that did not change with eye movements. Ophthalmological examination revealed macular traction. Patient 2 consulted due to left paroxysmal maxillary and mandibular pain of 3 weeks’ duration that worsened when chewing and was accompanied by a clicking sound; the physical examination revealed neurological stability and asymmetric bite and the patient was diagnosed with dysfunction of the left temporomandibular joint. Patient 3 presented a 3-week history of dizziness and showed changes with regard to her previous neurological examination. Patient 4 also reported a sensation of occasional transient instability progressing for one month, with no changes detected in the neurological examination. Both patients were diagnosed with non-specific dizziness, which resolved spontaneously.

A fifth patient, who was receiving treatment with interferon and with a history of flu-like reaction, consulted due to increased weakness (existing mild quadriparesis) and fever. The neurological examination ruled out an MS relapse. A blood test revealed severe leukocytosis, and the patient was finally diagnosed with Philadelphia chromosome–negative chronic myelogenous leukaemia. The patient progressed satisfactorily.

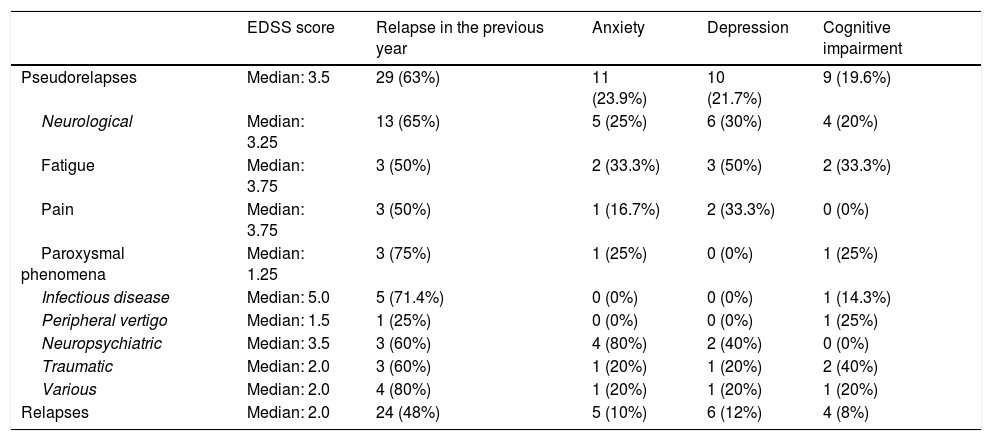

Influence of anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in patients with non-inflammatory symptoms (Table 3)Patients with fatigue (6) presented such comorbidities as anxiety (2 patients), depression (3), and cognitive impairment (2). Two patients reporting fatigue also presented anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment. We observed a statistically significant association between presence of depression and fatigue (P < .05) with regard to the control group (Table 3).

Role of EDSS score, anxiety, depression, and cognitive impairment in the different pseudorelapses.

| EDSS score | Relapse in the previous year | Anxiety | Depression | Cognitive impairment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudorelapses | Median: 3.5 | 29 (63%) | 11 (23.9%) | 10 (21.7%) | 9 (19.6%) |

| Neurological | Median: 3.25 | 13 (65%) | 5 (25%) | 6 (30%) | 4 (20%) |

| Fatigue | Median: 3.75 | 3 (50%) | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (50%) | 2 (33.3%) |

| Pain | Median: 3.75 | 3 (50%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Paroxysmal phenomena | Median: 1.25 | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| Infectious disease | Median: 5.0 | 5 (71.4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (14.3%) |

| Peripheral vertigo | Median: 1.5 | 1 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (25%) |

| Neuropsychiatric | Median: 3.5 | 3 (60%) | 4 (80%) | 2 (40%) | 0 (0%) |

| Traumatic | Median: 2.0 | 3 (60%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 2 (40%) |

| Various | Median: 2.0 | 4 (80%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) | 1 (20%) |

| Relapses | Median: 2.0 | 24 (48%) | 5 (10%) | 6 (12%) | 4 (8%) |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale.

In the 5 patients who attended due to non-inflammatory symptoms of neuropsychiatric origin (5 patients), history of anxiety (4 patients, 80%) was significantly more frequent (P = .003) than in the remaining patients with relapses (P = .002) or non-inflammatory symptoms (P = .009). No significant differences were observed in history of depression (2 patients, 40%) or cognitive impairment (0 patients, 0%) in the comparison against patients with relapses and non-inflammatory symptoms.

In patients consulting due to pain, paroxysmal phenomena, infection, traumatic injury, vertigo, or other causes, we observed no significant differences with regard to presence of these comorbidities.

Management of non-inflammatory symptoms (Table 2)Twenty-nine of the 46 patients (63%) who consulted due to non-inflammatory symptoms received some kind of pharmacological treatment prescribed by the day hospital to alleviate symptoms. Thirteen patients (28%) were referred to other specialties (rehabilitation, traumatology, otorhinolaryngology, psychiatry, internal medicine, and haematology).

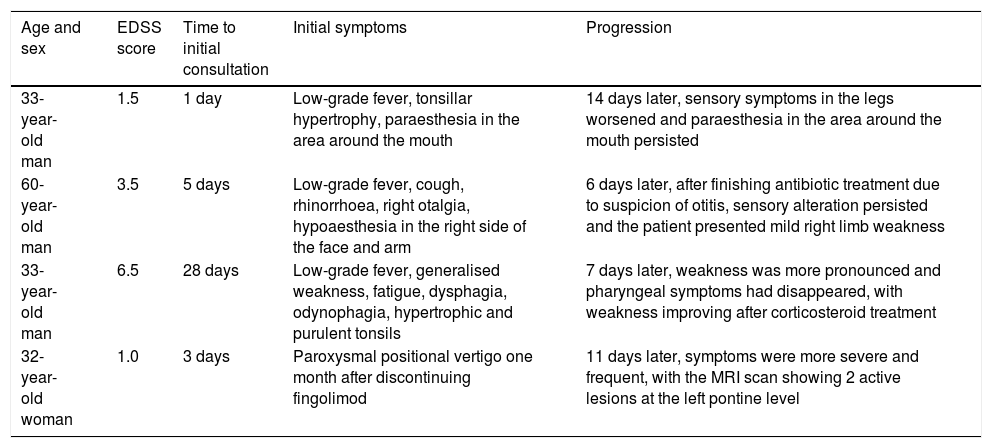

Patients initially misdiagnosed with pseudorelapseOf the total of 50 patients with an initial diagnosis of pseudorelapse, 4 (8%) were eventually diagnosed with a relapse (Table 4).

Patients with initial misdiagnosis of relapse.

| Age and sex | EDSS score | Time to initial consultation | Initial symptoms | Progression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33-year-old man | 1.5 | 1 day | Low-grade fever, tonsillar hypertrophy, paraesthesia in the area around the mouth | 14 days later, sensory symptoms in the legs worsened and paraesthesia in the area around the mouth persisted |

| 60-year-old man | 3.5 | 5 days | Low-grade fever, cough, rhinorrhoea, right otalgia, hypoaesthesia in the right side of the face and arm | 6 days later, after finishing antibiotic treatment due to suspicion of otitis, sensory alteration persisted and the patient presented mild right limb weakness |

| 33-year-old man | 6.5 | 28 days | Low-grade fever, generalised weakness, fatigue, dysphagia, odynophagia, hypertrophic and purulent tonsils | 7 days later, weakness was more pronounced and pharyngeal symptoms had disappeared, with weakness improving after corticosteroid treatment |

| 32-year-old woman | 1.0 | 3 days | Paroxysmal positional vertigo one month after discontinuing fingolimod | 11 days later, symptoms were more severe and frequent, with the MRI scan showing 2 active lesions at the left pontine level |

EDSS: Expanded Disability Status Scale; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Time from symptom onset to emergency department consultation was shorter when the patient presented a true relapse rather than a non-inflammatory symptom, although differences were not statistically significant. We also observed that the time to consultation was shorter in patients initially misdiagnosed with pseudorelapse than in patients with actual non-inflammatory symptoms. Time to consultation of patients with non-inflammatory symptoms of neurological origin (fatigue, pain, and paroxysmal phenomena) was significantly higher than in those with non-inflammatory symptoms of other origins, and significantly higher than in patients with true relapses. No relevant differences were observed in the remaining parameters.

DiscussionDiagnosis of an MS relapse is based on the medical history and physical examination of the patient. We analysed patients’ emergency consultations due to suspicion of relapse and assessed the symptoms that, in our opinion, were not caused by inflammatory activity of the disease. There is no clear definition of pseudorelapse in the literature, although the term is frequently used.1 The term pseudorelapse is not included in the latest MS diagnostic criteria2 but was included in the 2001 criteria,3 exclusively referring to symptoms caused by increased temperature or infection. However, the term pseudorelapse has also been used in the literature to describe other situations that may be confused for relapses of the disease but are not necessarily caused by an increase in temperature or infection.4 In our study, we use the term “symptoms of non-inflammatory origin” for any diagnosis other than relapse, whether or not they were caused by infections or increased temperature.

Our main contribution is the observation that neurological symptoms due to MS were the main reason for emergency consultation due to suspicion of MS relapse; the most frequently reported in our study were fatigue and pain. Furthermore, and contrary to expectations, increased temperature and infectious aetiologies were a less frequent non-inflammatory cause for consultation. We were also able to quantify the percentage of patients with relapses that were not identified at the first consultation (8%). With regard to this, we should underscore that there are no similar data in the literature against which to compare. Factors potentially motivating the delay in the diagnosis of relapse and the subsequent treatment were mainly the presence of concurrent infectious symptoms and, to a lesser degree (one case), paroxysmal vestibular symptoms.

Some studies report increased inflammatory activity secondary to respiratory and urinary tract infections5–8; therefore, it is important to inform patients with MS and infectious symptoms of this possibility. Regarding vertigo, the most frequent cause for consultation in patients with MS presenting vertigo symptoms and no other neurological signs is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo,9 although numerous cases have been described of true vestibular pseudoneuritis caused by lesions around the fourth ventricle, vestibular nuclei and vestibular nerve entry zone, and cerebellum.10,11

In other clinical contexts, doubts may also arise as to whether or not patients’ symptoms are due to the inflammatory activity of the disease: the literature reports a relapse manifesting exclusively as fatigue.12 However, fatigue is generally considered to be caused not by demyelinating or acute inflammatory lesions but by neuroendocrine alterations,13,14 with a dysruption of the cortico-subcortical circuits being responsible for the lesions.15 These theories may also explain the presence of such other comorbidites as depression, which are frequently associated with fatigue,16 as observed in our study. Regarding pain, in the case of trigeminal and other neuralgias, there is evidence that these conditions may be caused by acute lesions.17 In the case of our patient with trigeminal neuralgia, we believe he presented a pseudorelapse, as he had previously manifested similar symptoms in the absence of MS inflammatory activity. In any case, interruption of the spinothalamic tracts by either acute or old lesions, mixed pain, or spasticity may be the cause of pain.18,19 Paroxysmal phenomena may also be due to acute or old lesions20–24 that interrupt ephaptic transmission in the spinothalamic or thalamocortical tracts.25 In general, they are considered to be caused by a new attack when the symptom is repeated several times for more than 24 hours; occasionally, they occur very frequently.21,23 Paroxysmal symptoms may take several forms: dysarthria,22–27 ataxia,26,27 dyskinesia,20,21 dystonia,28 and other movement disorders; motor symptoms; paroxysmal sensory symptoms29; and even paroxysmal hypothermia30 have been described in association with MS lesions. Patients in our series presented mild paroxysmal symptoms, and only half required symptomatic treatment. In summary, where symptoms are atypical or of limited value for localising the lesion, it is difficult to determine whether they are caused by a new or an old lesion. The generalised use of MRI and the validation of new biomarkers may improve the management of these patients.

In a series of 371 patients with MS who attended emergency consultations, Tallantyre et al.31 observed that 58% consulted due to relapses and 31% (99 patients) consulted due to poor symptom control. The percentages of fatigue and pain were similar; it is therefore surprising that in our series only one patient consulted due to pain plus spasticity. This may be due to the lower EDSS scores in our patients. We should also highlight that some final diagnoses were severe, particularly in our series: a patient attended due to generalised weakness and fever was finally diagnosed with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Tallantyre et al.31 treated a patient with pulmonary thromboembolism and another with thyrotoxicosis. Given these examples, we should be conscious of multiple aetiologies and promote rapid access to other specialties for these patients, when necessary.

Our study presents some limitations, including a selection bias, as we only considered cases of patients who attended emergency consultations and not patients with acute- or subacute-onset symptoms which due to their lack of severity or other causes, did not lead to an emergency consultation. As it is mainly descriptive, our study does not include any blinded rater. We did not conduct statistical corrections for the multiple variables analysed: any inferential consideration should be interpreted with caution as this was not the primary endpoint of the study and statistics were calculated merely for exploratory purposes.

In short, there are numerous reasons besides relapses for emergency consultations for multiple sclerosis. Facilitating rapid access to MS units and reassessing patients who have experienced relapses and pseudorelapses may improve patient care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez de Antonio L.A., García Castañón I., Aguilar-Amat Prior M.J., Puertas I., González Suárez I., Oreja Guevara C. Causas no inflamatorias de consulta urgente en esclerosis multiple. Neurología. 2021;36:403–411.