Perhaps the most famous brain injury in history was a penetrating wound suffered by a railroad worker named Phineas Gage on September 13, 1848. Twelve years after his injury, on the 21st of May, 1860 Phineas Gage died of an epileptic seizure. In 1868 Dr. Harlow gave an outline of Gage's case history and first disclosed his remarkable personality change. One might think this report would assure Gage a permanent place in the annals of neurology, but this was not the case. There was a good reason for this neglect: hardly anyone knew about Harlow's 1868 report. Dr. David Ferrier, an early proponent of the localisation of cerebral function, rescued Gage from obscurity and used the case as the highlight of his famous 1878 Goulstonian lectures. Gage had, through a tragic natural experiment, provided proof of what Ferrier's studies showed: the pre-frontal cortex was not a “non-functional” brain area. A rod going through the prefrontal cortex of Phineas Gage signalled the beginning of the quest to understand the enigmas of this fascinating region of the brain.

Tal vez el caso de daño cerebral más famoso de la historia sea el sufrido por un trabajador del ferrocarril llamado Phineas Gage el 13 de septiembre de 1848; 12 años después, el 21 de mayo 1860, Gage muere tras una crisis comicial. En 1868 el Dr. Harlow publica el caso, describiendo por primera vez los cambios de personalidad experimentados por Gage tras la lesión. Uno pensaría que este artículo es el responsable de asegurar a Gage un lugar permanente en los anales de la neurología. Sin embargo no será así: pocas personas conocerán de la existencia de este artículo. No será hasta finales de la década de 1870 que Phineas Gage sea rescatado del olvido de la mano del Dr. David Ferrier, uno de los primeros defensores de la localización de la función cerebral. Para Ferrier Gage constituirá un trágico experimento natural que le permitirá corroborar que el córtex prefrontal no es un área no-funcional del cerebro. De tal forma, la lesión causada por una barra de hierro en el córtex prefrontal de Phineas Gage marcará los inicios de la investigación para comprender el enigma de esta fascinante región del cerebro.

“(…) the powder exploded, carrying an iron instrument through his head an inch and a fourth in circumference, and three feet and eight inches in length, which he was using at the time. The iron entered on the side of his face, shattering the upper jaw, and passing back of the left eye, and out at the top of the head. The most singular circumstances connected with this melancholy affair is, that he was alive at two o’clock this afternoon, and in full possession of his reason, and free from pain.”

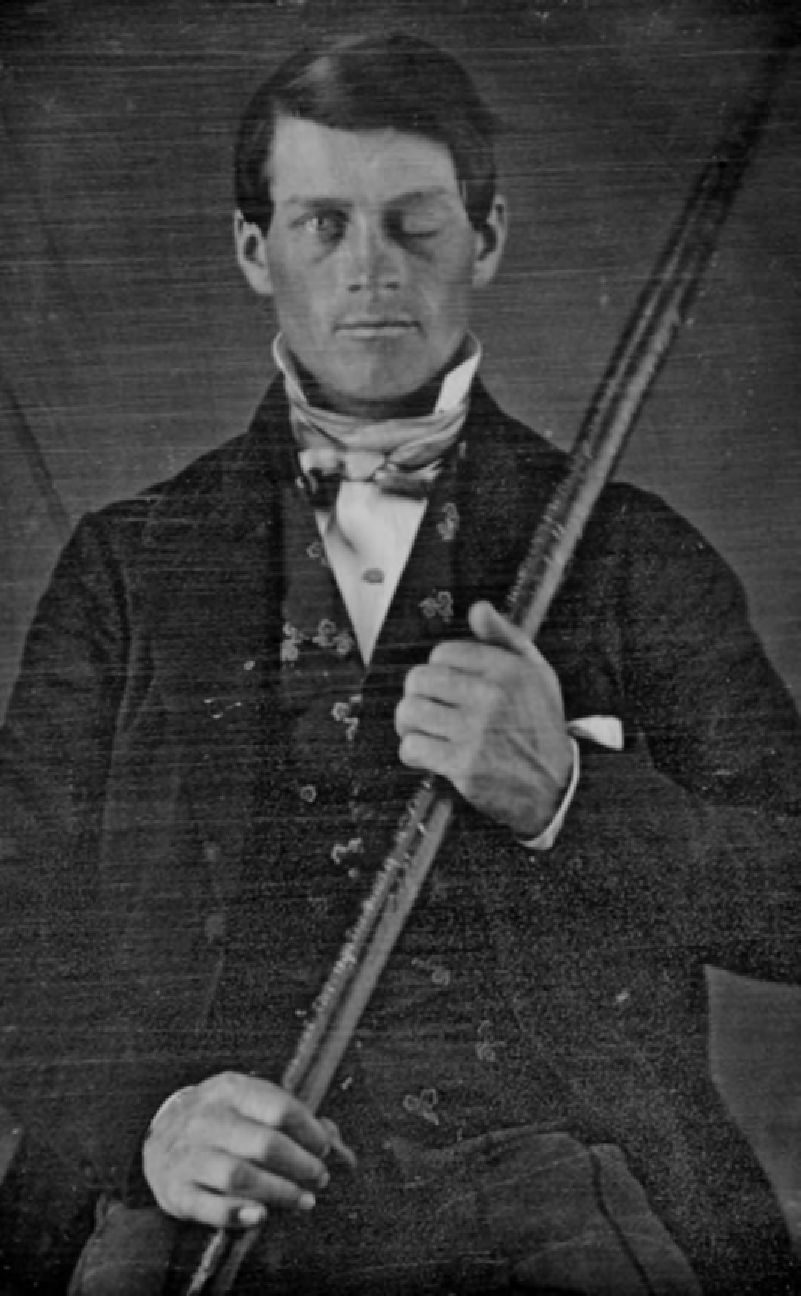

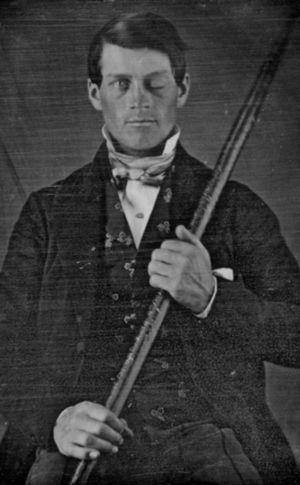

This brief news story, published in the Free Soil Union on 14 September 1848, is the first known description of the incredible accident suffered by Phineas Gage (Fig. 1). Gage, a 25-year-old foreman, was directing a group of men who were building the railway line between Rutland and Burlington in the state of Vermont in New England. They were in charge of clearing and levelling the rocky terrain along the future railway line. The fateful accident took place on 13 September 1848, at 4:30pm, near the town of Cavendish. As they had done many times before, Gage and his team drilled a deep hole in the rock, filled it with gunpowder, and packed it down with a tamping iron. However, this time the friction of the rod against the rock produced a spark, which caused an explosion. The tamping iron was ejected with great force and hit Gage in the face, entering the left cheek and passing through the frontal part of his skull.a Gage fell to the ground, but a few minutes later he started to react, to the workers’ surprise. His team took him to the hotel run by Joseph Adams in Cavendish. He got out of the cart on his own and sat down on the front steps of the house. He was conscious and able to describe the circumstances of the accident to those present. Edward Higginson Williams was the first doctor to arrive. Gage, who was seated on a chair, greeted him, saying “Doctor, here is business enough for you”. An hour later, Dr John Martyn Harlow visited the house. Under his medical care, Gage was able to survive the accident.a The doctor's first objective was to stop the abundant haemorrhage caused by the iron rod and eliminate the bone fragments remaining in the wound. In addition, Harlow facilitated drainage of the wound by elevating Gage's head. In the weeks that followed the accident, the main objective was to treat the infection that had developed in the injured region. Following the antiphlogistic principles of the early 19th century, Harlow used several emetic and cathartic agents (colchicum, rhubarb, mercury chloride, and others) in order to cleanse the organism of the “element” causing inflammation. On 18 November 1848, 65 days after the accident, Gage's condition showed clear signs of improvement; Harlow visited him for the last time in April 1849 and observed that his state of health was good. More than 17 years would pass before Harlow had any news of Gage. He would then able to reconstruct the events that took place between the spring of 1849 and Gage's death. According to Gage's mother, he had lived and worked in Valparaíso (Chile) during 8 years, but in June 1859 he decided to return to the United States, and journeyed to San Francisco. In February 1860, Gage suffered what appeared to be the first of a series of convulsions. He died on 21 May 1860 as a result of one of those convulsions.

Numerous publications report the events (real or imagined) that took place on the day of the accident. Nevertheless, there are few texts written by first-hand acquaintances of Phineas Gage. The first example, written by Dr Harlow in November 1848, is a letter addressed to the editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal2 in which he describes the circumstances surrounding the accident and the medical treatment which Gage received. Two months later, in January 1849, the same journal published a note only 5 lines long which indicated that the patient's physical and mental states were improving.3 The second text was published in the American Journal of the Medical Sciences by a young doctor from Boston, Henry J. Bigelow, a professor of surgery at Harvard University. The extraordinary case of Gage was published in several newspapers and caught Bigelow's interest. Like many other doctors and scientists of that time, he was sceptical about the authenticity of the case described by Harlow. Between November 1849 and January 1850, Bigelow examined Gage in order to shed light on this “medical curiosity”. Soon after, he published his conclusions regarding the case.4 Bigelow began his article with a list of different statements testifying to the veracity of the case, knowing that it might be called into question. As a result, the third and last direct account of the extraordinary case of Phineas Gage was published two decades after the accident.

On 3 June 1868, a Wednesday, Dr Harlow presented his case report at the annual meeting of the Massachusetts Medical Society, under the title of Recovery from the passage of an iron bar through the head. Harlow described the accident, the circumstances, the medical treatment received by the patient, and the patient's subsequent recovery. He also provided information about Gage's life after the accident and until his death. This presentation was the first occasion on which Harlow described the behavioural changes which Gage underwent after the accident.5 “The balance between his intellectual faculties and animal propensities, seems to have been destroyed. He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity (…), manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint of advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operation, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible.” (Harlow, 1868:339–40). After a favourable reception,6 the presentation was published the same year in Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society. One might think that this article would ensure Phineas Gage his place in the annals of neurology, but this was not the case. Publications of the Massachusetts Medical Society was a journal with a very low circulation; Harlow's article had little impact, and was soon forgotten. In 1878, the Phineas Gage case began to receive scrutiny. At present, 160 years after the accident, his case is famous among the scientific community. David Ferrier, one of the founders of English neurology (along with John J. Jackson, Richard Caton and William R. Gowers), won recognition for Harlow's contribution with his lecture The localisation of cerebral diseases.

The purpose of this article is to examine the case of Phineas Gage in its historical context, and in the context of how the study of the neuroanatomical basis of mental activity has evolved. We therefore include a general summary of the main changes and paradigm shifts that took place in this field of knowledge between the 18th and 19th centuries.

Franz Joseph Gall and brain physiologyThe importance of the role the cerebral cortex plays in mental activity is now universally accepted. Nevertheless, despite the contributions of authors such as Thomas Willis (1621–1675) or Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), this brain structure was thought to have no function in mental activity until the 19th century. Rather, it was thought to play a protective role, as evidenced by its name “cortex”, from Latin corticea [bark or cork]. The persistence of theories stating that brain activity takes place in the ventricular system meant that the cerebral cortex was considered a mere covering for the ventricles.7 It was not until the late 18th century that Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) linked the cerebral cortex to mental activity. Gall stated that the affective and intellectual faculties were located in the cerebral cortex. However, like his contemporaries, he still identified the striatum as the outermost limit for the motor nerve bundles, and the thalamus as the outermost limit for sensory endings. Gall's theory was that affective and intellectual faculties were located in specific regions of the cerebral cortex, and that there was a parallel between cortex development and the degree to which those faculties were expressed, as evidenced by a subject's behaviour. He initially called his doctrine Schädellehre (doctrine of the skull) before changing it to Organologie, and last of all, physiologie de cerveau. Gall never accepted the terms ‘phrenology’, ‘craniology’, or ‘cranioscopy’.8

Gall's postulates were revolutionary in that they provided the basis for the physiological study of the central nervous system and division of the cerebral cortex into different functional areas. Nevertheless, he soon found himself criticised by the academic, religious, and political spheres.9 The last Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Francis II, published a decree in 1801 forbidding Gall to organise lectures and publish manuscripts. This decree accused Gall of disseminating ideas contrary to morality and religion through his lectures. In France, Napoleon I ordered the French naturalist George Cuvier (1769–1832) to organise a committee of experts from the Académie des Sciences for the purpose of evaluating Gall's theses.8 A key figure among these experts was Marie-Jean-Pierre Flourens (1794–1867). In contrast to Gall's view of the cerebral cortex, Flourens held that this brain region was homogeneous and functioned as a whole. Between 1820 and 1840, Flourens surgically resected different parts of the brain in various animals, especially pigeons. Although he observed a certain degree of correspondence between the location of the lesion and loss of specific brain functions, the effects of destroying cerebral tissue were generally diffuse. On this basis, he concluded that all regions in the cerebral cortex take part in higher mental functions by acting as a single unit.10 Flourens’ thesis was quickly accepted by the scientific community and remained the dominant paradigm well into the second part of the 19th century. Despite the differences between the two scholars’ views about the functional organisation of the cerebral cortex, Gall and Flourens both agreed that this brain structure plays an important role in the mental activity. This replaced the theory that the cerebral cortex played only a protective function.

David Ferrier, Phineas Gage, and the functional organisation of the cerebral cortexIn 1848, when Phineas Gage suffered the accident, the cerebral cortex was still considered a homogeneous structure with no differentiated functions. Advances in the neuroanatomical understanding of this brain structure, together with detailed descriptions of symptoms in neurological patients, gradually changed the view of the cerebral cortex which Flourens had propounded. At the beginning of the 19th century, neuroanatomical knowledge of the cerebral cortex was limited. In 1807, François Chaussier divided the cerebral surface into 4 lobes: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital. The same author devised the terms ‘frontal’, ‘temporal’, and ‘occipital’ to refer to the anterior, medial-inferior and posterior areas of the brain, respectively.11 It was not until the mid 19th century that the brain convolutions would be described as they are today. Broca's contributions and Fritsch and Hitzing's experiments on brain excitability were particularly important to the study of brain function. In 1861, Paul Broca (1824–1880) presented the findings from post-mortem anatomical studies carried out in 2 patients who had suffered significant loss of expressive language. In both cases, anatomical studies showed a localised lesion in the third convolution of the left frontal lobe. This was the first evidence to be accepted by the scientific community which showed the link between a cognitive function and a specific area of the cerebral cortex. The studies on brain excitability published in 1870 by Gustav Theodor Fritsch (1838–1927) and Eduard Hitzing (1838–1907) constituted a new attack on Flourens’ paradigm. Flourens’ writings stated that the cerebral cortex was equipotential and that this part of the brain had nothing to do with motor functions. Fritsch and Hitzing showed that electric stimulation of the frontal cortex in several species of mammals causes specific muscle groups to contract. This finding demonstrated the presence of independent cerebral regions which are responsible for specific functions.11,12

Influenced by Fritsch and Hitzing's studies, the English doctor David Ferrier (1843–1928) began systematically examining the cerebral cortex in different vertebrates. His aim was to confirm his colleague John Hughlings Jackson's hypotheses regarding cortical localisation. Based on clinical observations in epileptic patients, John Hughlings Jackson had postulated that sensory and motor functions are represented in the cerebral cortex in an organised and localised way. Ferrier created a precise map of motor and sensory functions in the cortex by extirpating cerebral tissue and stimulating the brain using alternating current. In 1876, he published the results in his book The Functions of the Brain. One of his main findings was obtained by surgically removing a large part of the prefrontal cortex in 3 monkeys. None of them showed changes in their sensory, motor, or perceptual processes. Ferrier established a parallel between these findings and observations of human beings with massive frontal lobe lesions. The story of Phineas Gage is one of the cases Ferrier mentioned as an example of the limited functional consequences of frontal lobe lesions. Shortly thereafter, on 15 March 1878, Ferrier presented The localisation of cerebral diseases as part of the Gulstonian Lectures, which were organised by the Royal College of Physicians.13,14 In his presentation, Ferrier put forth his ideas regarding the link between specific cortical areas and specific functions, and stated that results obtained through animal experiments could be useful in diagnosing and treating neurological patients. In the section titled Lesions of the frontal lobes, Ferrier referred once again to the Phineas Gage case to illustrate the symptoms that result from lesions in this brain region. On this occasion, however, he stated that Gage suffered from behavioural changes as a result of the lesions he suffered in the accident.

What happened between the publication of The Functions of the Brain and the presentation of The localisation of cerebral diseases? Why did Ferrier change his mind so radically about the Phineas Gage case in only two years? In 1876, when The Functions of the Brain was published, Harlow (1848) and Bigelow (1850) were Ferrier's sources of information for the Gage case. None of them described behavioural changes in Gage after the accident. In fact, Bigelow concluded that even though a substantial part of Gage's brain was destroyed, he only experienced vision loss in the left eye, and his mental faculties appeared not to have been affected. Ferrier had probably heard of Harlow's article (1868) through secondary sources; in The Functions of the Brain he stated that Gage died 12 years after the accident, which coincides with that reported by Harlow (1868). However, Ferrier probably did not have direct access to the book in which Harlow described the behavioural changes suffered by Gage as a result of the unfortunate accident. On 12 October 1877, he wrote to Henry Pickering Bowditch, professor of physiology at Harvard University, to request further information regarding the location of Gage's lesions caused by the tamping iron.15 The French neurologist Eugene Dupuy opined that Gage did not experience any language disorders in spite of suffering “total destruction” of the left frontal lobe, clearly demonstrating the equipotentiality of the cerebral cortex. In 1868, Bowditch sent Ferrier a facsimile of the article published by Harlow. At a later date, Ferrier contacted Harlow to ask him for a copy of the texts he used to prepare his presentation before the Massachusetts Medical Society. Ferrier used them for his 1878 lecture The localisation of cerebral diseases.

Why did Dr. Harlow omit part of the information about Gage's case? Why did he not present the full report until 1868? Whatever led him to conceal Gage's changes in behaviour? Macmillan offers 2 possible explanations.1 According to this author, the theories about brain function which were dominant in 1848 would not have given credit to the reality which Harlow described in 1868. Changes in our understanding of brain function which were introduced between 1848 and 1868 permitted Harlow to describe Gage's case in more detail. The second of Macmillan's explanations suggests that Harlow concealed Gage's behavioural changes for ethical reasons. Harlow might have refrained from describing Phineas Gage in such a negative light while he was still alive (recall that he did not die until 12 years after his accident). Aside from Macmillan's explanations, Harlow may also have omitted details of the case so as to publish a more detailed article at a later time. Let us not forget that Harlow's first description of Gage was not a published article, but rather a letter sent to the editor of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal. In the closing of this letter, Harlow indicated that he had reserved some information which would be featured in a future communication. This delay in publishing the information would also have an impact on the study of the prefrontal cortex. Due to this delay, descriptions of the Phineas Gage case provided by Harlow (1848) and Bigelow (1850) were used until the early 1870s to describe this area of the brain as functionally negligible. David Ferrier's revival of the Phineas Gage case helped change this perspective.

Closing remarksIn 1868, during his presentation before the Massachusetts Medical Society, Harlow stated that Gage's lesion affected the best possible cerebral area in which to suffer injury. Although his comment seems surreal today, it reflects the concept of the prefrontal cortex that was dominant in the mid 19th century. These ideas stem from texts like those written by Sir Percivall Pott (1713–1788), the eminent 18th century English surgeon.17 After observing the effects of contusions in the anterior part of the brain, Pott wrote that lesions beneath the frontal bone have less severe consequences than those located in any other part of the brain. Systematic study of the cerebral cortex, beginning in the second half of the 19th century, made it possible to refute such beliefs and study this brain structure in depth. In 1854, Louis Pierre Gratiolet described the convolutions and fissures of the cerebral cortex.18 In 1866, William Turner defined the fissure of Rolando as the posterior limit of the frontal lobe. Two years later, Richard Owen subdivided the region along the anterior limits of the motor cortex into the following areas: superfrontal, midfrontal, subfrontal, ectofrontal and prefrontal. He was the first to use the term ‘prefrontal’.19 One direct effect of differentiating the regions of the cerebral cortex was that it became possible to run clinical studies comparing the effects of lesions located in different cortical regions, therefore enabling correlations between structures and their functions.

Between the time when the Phineas Gage case was published and the present day, many researchers have tried to solve the mysteries of the prefrontal cortex (Fig. 2). The complex idiosyncrasies of this enigmatic brain region have made this area of study a challenging one. As Hans-Lukas Teuber20 stated in his seminal article The Riddle of Frontal Lobe Function in Man, “Man's frontal lobes have always presented problems that seemed to exceed those encountered in studying other regions of his brain (…). There certainly is no other cerebral structure in which lesions can produce such a wide range of symptoms, from cruel alterations in character to mild changes in mood that seem to become undetectable in a year or two after the lesion.” (Teuber. 1964:25–26). However, progress in neuroscience in recent decades has contributed substantially to our knowledge of the different structures of the prefrontal cortex and the role it plays in behaviour modulation. Understanding the link between the structure and its processes is what allows us to shed light on the enigmas of the prefrontal cortex.

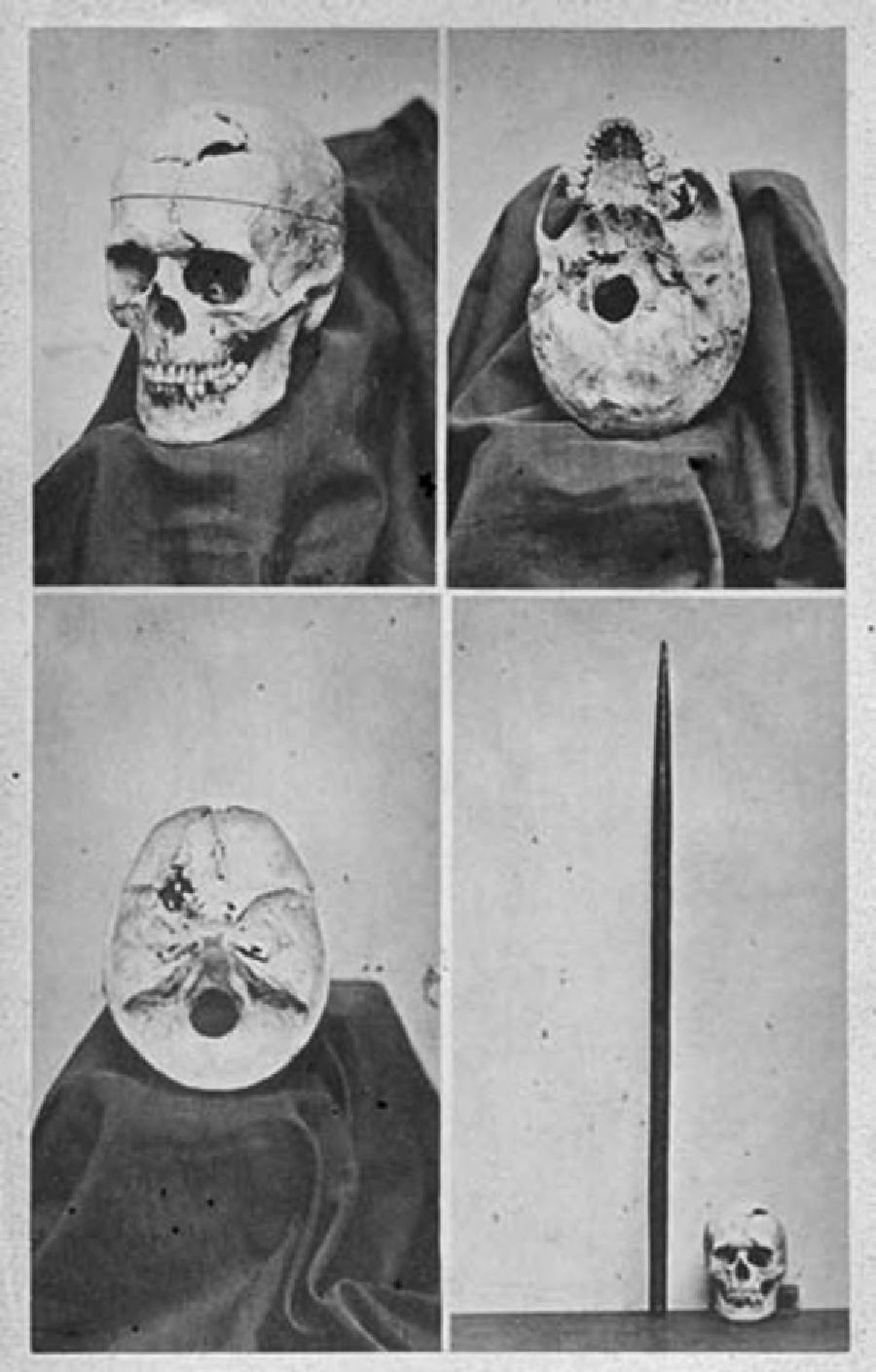

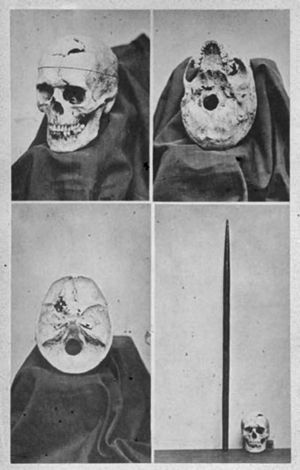

Photomontage showing 4 views of Gage's skull (a descriptive catalogue of the Warren Anatomical Museum, 1870).16

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

During the 1990s, Hanna Damasio et al. created a three-dimensional reconstruction of Gage's brain and the injury caused by the tamping iron. The image showed that the injury affected the ventromedial prefrontal region of both hemispheres. The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex remained in good condition in both hemispheres (Damasio H, Grabowski T, Frank R, Galaburda AM, Damasio AR. The return of Phineas Gage: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science. 1994;264:1102–5). In 2004, the radiology team at Hospital Brigham and Women's in Boston created a new reconstruction showing that lesions were limited to the left frontal lobe. The ventricular system and the vital vascular structures were not affected (Ratiu P, Talos IF, Haker S, Lieberman D, Everett P. The tale of Phineas Gage, digitally remastered. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:637–43).

Please cite this article as: García-Molina A. Phineas Gage y el enigma del córtex prefrontal. Neurología. 2012;27:370–5.