ADHD symptoms begin to appear at preschool age. ADHD may have a significant negative impact on academic performance. In Spain, there are no standardised tools for detecting ADHD at preschool age, nor is there data about the incidence of this disorder.

ObjectiveTo evaluate developmental factors and learning difficulties associated with probable ADHD and to assess the impact of ADHD in school performance.

MethodsWe conducted a population-based study with a stratified multistage proportional cluster sample design.

ResultsWe found significant differences between probable ADHD and parents’ perception of difficulties in expressive language, comprehension, and fine motor skills, as well as in emotions, concentration, behaviour, and relationships. Around 34% of preschool children with probable ADHD showed global learning difficulties, mainly in patients with the inattentive type. According to the multivariate analysis, learning difficulties were significantly associated with both delayed psychomotor development during the first 3 years of life (OR: 5.57) as assessed by parents, and probable ADHD (OR: 2.34)

ConclusionsThere is a connection between probable ADHD in preschool children and parents’ perception of difficulties in several dimensions of development and learning. Early detection of ADHD at preschool ages is necessary to start prompt and effective clinical and educational interventions.

Los síntomas del TDAH emergen a partir de la edad preescolar. El TDAH en preescolares implica una importante repercusión académica posterior. En España no hay instrumentos normalizados (idioma y cultura) para la detección del TDAH en preescolares ni disponemos de datos de su impacto.

ObjetivosEvaluar factores de desarrollo y dificultades de aprendizaje asociados con probable TDAH y valorar la repercusión del probable TDAH en el ámbito escolar en niños preescolares.

MétodosEstudio poblacional en el que se aplicó un muestreo polietápico-estratificado proporcional por conglomerados.

ResultadosDetectamos diferencias significativas entre probable TDAH y percepción parental de dificultades en el desarrollo del lenguaje expresivo, comprensión y psicomotricidad fina y en el área de emociones, concentración, conducta y relaciones. El 34% de preescolares con probable TDAH presentaban dificultades en el aprendizaje global. La interferencia se manifestó predominantemente en el subtipo inatento. En el análisis multivariante, las dificultades en el aprendizaje se asociaron a la presencia de un desarrollo psicomotor retrasado en los 3 primeros años de vida (OR: 5,57) valorado por los progenitores y al probable TDAH (OR: 2,34).

ConclusionesEl probable TDAH en preescolares se ve asociado a la percepción parental de dificultades en varias dimensiones del desarrollo y el aprendizaje. Es importante realizar una detección precoz del TDAH en la época preescolar para iniciar de forma temprana intervenciones clínicas y educativas efectivas.

Clinical manifestations of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) vary throughout a patient's life. In preschool children (3 to <7 years), who are still developing such skills as attention or impulse inhibition, establishing the boundary between normal and pathological inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity is not straightforward.1,2

During the preschool years, children acquire the social, behavioural, and academic skills necessary to perform satisfactorily in school. They learn to focus their attention, interact with their peers, and follow class rules. During this period, they also acquire basic literacy skills. Starting school without these skills increases the likelihood of performing poorly at school in the future.3

It is difficult to determine whether subsequent learning disorders are due to incomplete acquisition of basic skills or rather to the persistence of ADHD symptoms over time. Between 70% and 80% of preschool children with ADHD continue to display symptoms during school age4; 59% to 67% of these children will continue to experience ADHD symptoms during adolescence.5,6 Severity of ADHD symptoms during preschool age constitutes the main predictor of ADHD persistence at older ages.7

Multiple studies support an association between ADHD symptoms and poor school performance between the ages of 6 and 12 years.8,9 However, few studies have analysed this association in preschool children, and there are substantial methodological differences between them. Several retrospective studies have reported an association between poor overall performance in reading and writing tasks and the presence of ADHD symptoms during preschool age.10–12 Longitudinal studies have found that children displaying ADHD symptoms during the preschool years perform poorly in such areas as spelling, reading, and mathematics.13–15 The association between ADHD symptoms and school problems becomes more significant as children make their way through school.16

Children with predominantly inattentive-type ADHD display poorer academic performance than those with hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. According to Pastura et al.,17 inattention seems to be the factor of ADHD which is most strongly linked to poor academic performance. Other authors have also found a direct correlation between inattention and poorer reading18 and mathematics performance19 compared to children with other ADHD subtypes and controls.

ADHD research in Spain has focused on school children, although ADHD symptoms usually appear and begin to affect children's lives at younger ages.3,20–22

In light of the above, we decided to conduct a clinical epidemiological study including preschool children (ages 3 to <7 years). In order to diagnose ADHD in its early stages, we need to establish the limits between normal and pathological behaviour in preschool children and use screening tests specifically designed for our setting. Based on the hypothesis that attention disorders may predict future academic performance, our purpose was twofold: to determine which developmental factors and learning difficulties are associated with probable ADHD in preschool children, and to assess the impact of probable ADHD on school performance.

Patients and methodsStudy design and sample sizeWe conducted a population-based epidemiological study including all preschool children (3 to <7 years) from the autonomous communities of Navarre and La Rioja, amounting to a total of 30647 children. During the first phase, we selected a series of schools by systematic random sampling. In the second phase, we applied stratified sampling (by grade) and conglomerate sampling (classes per grade in each school) to select the participants. We excluded children whose parents did not sign informed consent forms and those with special educational needs due to severe neurodevelopmental disorders, sensory deficits, or psychopathological disorders (including ADHD). We obtained a minimum sample size of 1404 children, assuming a prevalence of ADHD of 4% in preschool children (precision of ±1%) and an estimated drop-out rate of 12%.

Our research group included healthcare professionals from Mendillorri Healthcare Centre and Clínica Universidad de Navarra, in Pamplona, and Labradores Healthcare Centre, in Logroño.

All children received an envelope with the informed consent form, a series of questionnaires, and the Spanish-language version of the ADHD Rating Scale IV for preschool children (ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES). Children's parents had to sign the informed consent forms and complete the questionnaires and return these documents to school within 7-10 days. Teachers had to complete the ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES for each of the children included in the study.

ToolsParents and preschool teachers completed the Spanish-language version of the ADHD-RS IV for preschool children23 (ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES) (to be published). The scale includes 18 items exploring the 18 ADHD symptoms proposed by the DSM-5, arranged into 2 subscales (inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity). Responses reflected the frequency of certain behaviours during the previous 6 months. There are 2 versions of the ADHD-RS IV: one for parents and the other for teachers (both were used in order to assess symptoms in at least 2 different settings). Each item is scored from 0 to 3 points (rarely or never, sometimes, often, very often).

By transforming raw scores into percentiles, we obtained normative data according to rater (parents or teachers), sex, age group, subscale (inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity), and the total scale. Scores equal to or above the 93rd percentile in the normative data were regarded as suggestive of probable ADHD.

Parents completed an ad hoc questionnaire to assess their children's psychomotor development (PMD) during their first 3 years of life and the presence of problems in expressive language, comprehension, fine and gross motor skills, and overall learning capacities at the time of inclusion.

The impact of these alterations in the family and school settings was evaluated with the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ),24 and more specifically the parent-rated “impact supplement” to the SDQ, which was adapted and translated into Spanish. This parent-rated questionnaire enables the assessment of difficulties experienced by preschool children in several daily living activities.

Statistical analysisWe performed a descriptive analysis of the variables. The bivariate analysis used the chi-square test for categorical variables and ANOVA for quantitative variables. The multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression model, with presence of learning difficulties as the dependent variable and all the variables showing significant alterations in univariate analysis as independent variables. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software version 20.

ResultsOur study gathered a total of 1426 preschool children with a mean age of 4.70 years (95% CI, 4.65-4.74) from 23 schools (11 in Navarre and 12 in La Rioja). Our sample displayed a homogeneous sex distribution (49.6% were boys).

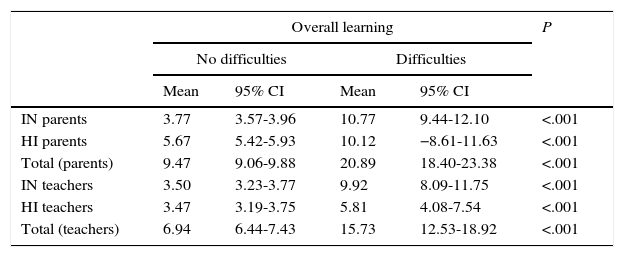

Mean scores on the ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES scale were higher in the group of children rated by their parents as having “some overall learning difficulties” than in those children with no learning difficulties. Differences were statistically significant for both subscales and for both rater categories (Table 1).

Mean ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES scores in our sample of 1426 preschool children (ages 3 to <7 years) in Navarre and La Rioja in children with and without overall learning difficulties.

| Overall learning | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No difficulties | Difficulties | ||||

| Mean | 95% CI | Mean | 95% CI | ||

| IN parents | 3.77 | 3.57-3.96 | 10.77 | 9.44-12.10 | <.001 |

| HI parents | 5.67 | 5.42-5.93 | 10.12 | −8.61-11.63 | <.001 |

| Total (parents) | 9.47 | 9.06-9.88 | 20.89 | 18.40-23.38 | <.001 |

| IN teachers | 3.50 | 3.23-3.77 | 9.92 | 8.09-11.75 | <.001 |

| HI teachers | 3.47 | 3.19-3.75 | 5.81 | 4.08-7.54 | <.001 |

| Total (teachers) | 6.94 | 6.44-7.43 | 15.73 | 12.53-18.92 | <.001 |

IN: inattention subscale; HI: hyperactivity-impulsivity subscale.

Parents reported overall learning difficulties in 34% of the children with probable ADHD vs 4.1% of the children with negative screening results for probable ADHD.

Of the preschool children with inattentive-type ADHD, 62.5% displayed overall learning difficulties according to parents’ reports; this percentage was statistically significant compared to combined-type (34.2%) and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD (0%).

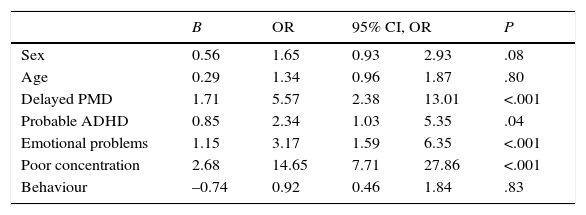

According to the multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for sex and age, learning difficulties were associated with presence of delayed PMD during the first 3 years of life (OR 5.57; 95% CI, 2.38-13.01), probable ADHD (OR 2.34; 95% CI, 1.03-5.35), emotional problems (OR 3.17; 95% CI, 1.59-6.35), and trouble concentrating (OR 14.65; 95% CI, 7.71-27.86) (Table 2).

Factors associated with learning difficulties in a sample of 1426 preschool children (ages 3 to <7) in Navarre and La Rioja.

| B | OR | 95% CI, OR | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.56 | 1.65 | 0.93 | 2.93 | .08 |

| Age | 0.29 | 1.34 | 0.96 | 1.87 | .80 |

| Delayed PMD | 1.71 | 5.57 | 2.38 | 13.01 | <.001 |

| Probable ADHD | 0.85 | 2.34 | 1.03 | 5.35 | .04 |

| Emotional problems | 1.15 | 3.17 | 1.59 | 6.35 | <.001 |

| Poor concentration | 2.68 | 14.65 | 7.71 | 27.86 | <.001 |

| Behaviour | –0.74 | 0.92 | 0.46 | 1.84 | .83 |

PMD: psychomotor development during the first 3 years of life; OR: odds ratio; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

We also observed differences in presence of probable ADHD and parent-reported delayed PMD during the first 3 years of life. According to parents’ reports, children with probable ADHD displayed delayed PMD compared to their peers (17.6% vs 3.1% of children without probable ADHD) (P<.05).

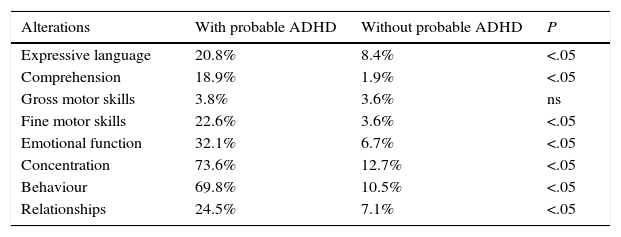

We also found a statistically significant association between probable ADHD and difficulties in expressive language, comprehension, and fine motor skills (Table 3). Parents reported expressive language difficulties in 20.8% of the children with probable ADHD vs 8.4% of those without and comprehension difficulties in 18.9% of the children with probable ADHD vs 1.9% of those without. Children with and without probable ADHD displayed no significant differences in gross motor skills (running, jumping, balance); however, they did show differences in fine motor skills (drawing, using a pair of scissors, writing). Poor fine motor skills were present in 22.6% of children with probable ADHD vs 3.6% of those without. According to parents’ reports, children with probable ADHD displayed more difficulties than those without in the following areas: emotional functioning (32.1% vs 6.7%), concentration (73.6% vs 12.7%), behaviour (69.8% vs 10.5%), and relationships with their peers (24.5% vs 7.1%) (P<.05).

Presence of alterations in emotional function, concentration, behaviour, personal relationships, and different areas of psychomotor development in preschool children with and without probable ADHD according to the SDQ.

| Alterations | With probable ADHD | Without probable ADHD | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expressive language | 20.8% | 8.4% | <.05 |

| Comprehension | 18.9% | 1.9% | <.05 |

| Gross motor skills | 3.8% | 3.6% | ns |

| Fine motor skills | 22.6% | 3.6% | <.05 |

| Emotional function | 32.1% | 6.7% | <.05 |

| Concentration | 73.6% | 12.7% | <.05 |

| Behaviour | 69.8% | 10.5% | <.05 |

| Relationships | 24.5% | 7.1% | <.05 |

ns: not significant; ADHD: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

We used the SDQ to assess the functional impact of ADHD on school performance. Difficulties were experienced in the family and school settings by 88.9% of the children with probable ADHD vs 31.1% of those without. Severity of these difficulties was higher in the group of children with probable ADHD; 65.9% of these children had marked or severe difficulties. In 85.5% of the cases, these problems were already present over 12 months prior to inclusion in the study. These alterations significantly affect these children's relationships with their peers in 28.3% of cases and their school performance in 48.9% of cases.

DiscussionVery few studies have addressed the association between ADHD in preschool children and school performance, probably due to a lack of diagnostic and screening tools specifically designed for this population. This is the first population-based study into the epidemiology and impact of ADHD in preschool children to be conducted in Spain. Our study used the ADHD-RS-IV-P, which has been shown to have good psychometric properties,23 to detect ADHD in preschool children; we created a Spanish-language version of the tool (ADHD-RS-IV-P-ES) for our study.

An association was observed between probable ADHD and parent-reported overall learning difficulties, which were already present in the children at school age; these findings are consistent with the results of previous studies reporting a significantly higher prevalence of learning disorders in children with ADHD than in the general population.25

According to our findings and to those reported by other researchers, we should focus on detecting impaired acquisition of basic literacy skills in preschool children. These skills are developmental precursors to reading and writing and strong predictors of subsequent school performance.26 Several prospective studies have shown an association between incomplete acquisition of basic skills and subsequent poor school performance in children with ADHD.14,15,18 Retrospective studies also report an association between the presence of ADHD symptoms during preschool and poorer reading and writing skills at older ages.10–12 Other studies report conflicting results, however. Montiel-Nava et al.,27 for example, conclude that children with ADHD have normal reading and writing skills for their age and school grade. Velting and Whitehurst28 found no strong correlation between basic literacy skills and presence of ADHD in preschool children. These discrepancies may be due to small sample size, as in the first of these studies (N=394), or the excessive emphasis placed on hyperactivity symptoms over inattention, as in the second study.

Preschool children with probable ADHD and learning difficulties in our sample mainly had inattentive-type ADHD (62.5%); our findings are in line with those reported by Hannah,29 who found that 70% of children with inattentive-type ADHD had academic difficulties. This supports the hypothesis that inattention alone may be the main factor in ADHD responsible for poor school performance.17 However, these results should be interpreted with caution, since very few children with inattentive-type ADHD are identified at preschool age. Most of these cases go undetected or are misdiagnosed.30

The parents of children with probable ADHD reported delayed PMD during the first 3 years of life compared to other children of the same age. Based on parent-reported data, Vaquerizo-Madrid31 concluded that delayed PMD is normal in children diagnosed with ADHD. However, the questionnaire used by this researcher is applicable to a wider population than ours (first 5 years of life vs first 3 years). Differences may be more marked during the first years and normalise thereafter; in any case, this is an interesting topic for future research.

In our sample, one in every 5 children with probable ADHD displayed alterations in expressive language at the time of the study; a similar proportion was observed in comprehension (18.9%). This may be due to the fact that linguistic tasks require a certain level of attention and inhibitory control, which are severely affected in ADHD. These children may be missing a great deal of verbal information due to this executive dysfunction. According to the literature, children with ADHD are more likely to perform poorly at school, especially in reading and writing tasks.32 In line with the findings reported by Artigas-Pallarés32 and Shaywitz et al.,33 our results indicate that language problems may play a crucial role in early detection of ADHD. However, further research is necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

In our sample, one in every 4 preschool children with probable ADHD displayed difficulties with fine motor skills; similarly, children with ADHD in the study by Poeta and Rosa-Neto34 exhibited normal to poor fine motor skills. According to Vaquerizo-Madrid,31 poor motor function is one of the main alterations associated with ADHD; the author goes on to suggest that quality of motor function during the first 5 to 6 years of life may act as a predictor of ADHD symptoms. Poor fine motor skills may be due to a lack of adequate concentration and inhibitory control, much in the same way as poor language function requires a certain level of inhibitory control.

The SDQ revealed that our sample of children with ADHD had difficulties relating with their peers and problems affecting school performance. According to Rodríguez-Salinas et al.,35 children with ADHD display not only learning difficulties but also emotional problems manifesting particularly in the school setting and affecting their quality of life. The studies by August et al.36 and DuPaul et al.37 detected integration problems in addition to academic difficulties. The above shows that social problems associated with ADHD are already present at preschool ages.

One of the limitations of our study is the fact that we did not analyse such other factors as the family's socioeconomic level and the parents’ education level. Given the population-based randomised design of our study, we assume that our sample includes children from all socioeconomic levels. Furthermore, we have not specifically addressed immigration, although we assume that children with linguistic or cultural adaptation problems constitute only a small percentage of the total sample (below 14% of the total population).

Our study had other limitations: we did not confirm presence of ADHD with clinical interviews but rather used parent- and teacher-reported data only (this is why we use the term “probable ADHD”); and previous diagnosis of neurodevelopmental disorder and/or special educational needs was included as an exclusion criterion. The latter limitation may have biased our results given that our sample may be “healthier” than the real population.

Early detection of ADHD in preschool children is essential to starting clinical and educational interventions early. Future research should focus on developing effective treatment strategies for these children.

FundingThis study has received no public or private funding.

Conflicts of interestAlthough the present study was not financed by any public or private institutions, the authors wish to state the following:

Juan J. Marín-Méndez's department has received funding from the government of Navarre, Caja Navarra Foundation, QPEA Foundation, Institute of Health Carlos III, and PIUNA.

César Soutullo's department has received funding from Caja Navarra Foundation, Lundbeck, PIUNA, Shire, and TEVA. César Soutullo has received fees as a consultant from: Quality Agency of Spain's National Health System (Clinical practice guidelines for ADHD and depression); Editorial Médica Panamericana; Eli Lilly; EUNETHYDIS); Alicia Koplowitz Foundation; Institute of Health Carlos III (FIS); Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services, and Equality (Spanish National Health System Mental Health Strategy); NeuroTech Solutions; Rubió; the Scottish Experimental and Translational Medicine Research Committee; and Shire. Furthermore, Dr Soutullo has received fees as a speaker on continuing medical education from: Eli Lilly, Shire, Universidad Internacional Menéndez Pelayo, Universidad Internacional de La Rioja (UNIR). He has also received copyright fees from: DOYMA, Editorial Médica Panamericana, ECUNSA, and Mayo Ediciones.

We would like to thank the Departments of Education, Training, and Employment of the autonomous communities of La Rioja and Navarre, the teachers and counsellors of the participating schools, and the participating children's parents. We also wish to thank Enrique Ramalle-Gomara, from the Department of Disease Epidemiology and Prevention of La Rioja, for his valuable help.

Please cite this article as: Marín-Méndez JJ, Borra-Ruiz MC, Álvarez-Gómez MJ, Soutullo Esperón C. Desarrollo psicomotor y dificultades del aprendizaje en preescolares con probable trastorno por déficit de atención e hiperactividad. Estudio epidemiológico en Navarra y La Rioja. Neurología. 2017;32:487–493.

This study was presented at the 38th Annual Meeting of the SENEP, held in Logroño, Spain (21-23 May 2015), where it was chosen as one of the winning presentations.