The Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) and the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) are widely used in clinical practice. The ROCF assesses visual perception, constructional praxis, and visuo-spatial memory. The FCSRT assesses verbal learning and memory.

ObjectiveIn this study, as part of the Spanish normative studies project in young adults (NEURONORMA young adults), we present age- and education-adjusted normative data for both tests obtained by using linear regression techniques.

Materials and methodsThe sample consisted of 179 healthy participants ranging in age from 18 to 49 years. We provide tables for converting raw scores to scaled scores in addition to tables with scores adjusted by socio-demographic factors.

ResultsThe results showed that education affects scores for some of the memory tests and the figure-copying task. Age was only found to have an effect on the performance of visuo-spatial memory tests, and the effect of sex was negligible.

ConclusionsThe normative data obtained will be extremely useful in the clinical neuropsychological evaluation of young Spanish adults.

El test Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF) y el Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) son pruebas ampliamente utilizadas en la práctica clínica. El ROCF es de gran utilidad para la exploración de la percepción visual, la praxis constructiva y la memoria visuoespacial. El FCSRT evalúa aprendizaje y memoria verbal.

ObjetivoEn el presente estudio, que forma parte del proyecto de obtención de datos normativos españoles en adultos jóvenes (proyecto NEURONORMA jóvenes), se aportan datos normativos ajustados por edad y escolaridad para ambos test mediante la aplicación de regresiones lineales.

Material y métodosSe incluyó a 179 participantes sanos de entre 18 y 49 años de edad. Se aportan tablas para convertir las puntuaciones brutas en escalares, así como tablas de ajuste por los factores sociodemográficos.

ResultadosLos resultados obtenidos muestran influencia de la escolaridad en diversas variables de memoria y en la copia de la figura. La edad únicamente afecta el rendimiento en memoria visuoespacial y el efecto del género es despreciable.

ConclusionesLas referencias obtenidas son de gran utilidad clínica para la evaluación neuropsicológica de población adulta joven española.

Memory assessment is an important component in the neuropsychological evaluation process since the most common concerns of patients requesting a neurological consultation are memory-related. In addition to the neurodegeneration typical of ageing, memory disorders are also observed in patients with neurological diseases that frequently present in the younger population.

Having evaluation tools that are adapted to our setting is important, and appropriate normative data are needed in order to assess memory in the younger adult population. In the light of this situation, our study provides normative data from a test of visuoconstructive praxis and visual memory called the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure (ROCF),1,2 and the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test (FCSRT) for verbal memory3 in a younger Spanish population.

The ROCF provides data on visual perception, graphic visuoconstructive ability, visual memory, and planning and organisational ability.4–6 The literature includes studies of the test's sensitivity for detecting cognitive impairment affecting memory and executive function.7,8

This test was first developed by Rey1 and subsequently standardised by Osterrieth.2 The procedure for administering the test has changed considerably over time and several different scoring schemes are currently used. Some researchers provide the figure and ask the subject to recall it on a single occasion between 3 and 45minutes after having seen it.9 Another administration procedure consists of both immediate recall and 30-minute delayed recall of the figure after a recognition trial for elements in the figure.5

According to the literature, sociodemographic factors such as age, educational level, and sex have an effect on test performance. Researchers have observed decreases in scores beginning at the age of 70 years for both the copying and the recall tasks.6,10–15 Educational level is also described as having a significant effect on scores on all tasks. Performance is poorer among subjects with a low educational level.16–21 Concerning sex effect, results are contradictory. Some of the studies report better performance by males,21,22,25 while other studies were unable to corroborate that finding.5,7,8,16,17,22–25

The ROCF test includes multiple normative studies for the different test versions listed in certain compilations of neuropsychological tests.4,6,10 Meyers and Meyers26 propose an administration procedure that includes copying, both immediate and delayed recall, and recognition tasks. They also provide normative data from a sample of subjects aged between 18 and 89. The manual published by Mitrushina et al.6 is a review of different normalisation studies, including normative data in a Spanish-speaking population.11,16,27,28 New normative data from a sample of Spanish subjects aged 50 and older have recently been published for this test administration scheme.17

The FCSRT test is used to assess learning and verbal memory capacities. This test allows researchers to evaluate the ability to evoke a memory, as well as the abilities to record and retain information and coordinate between the encoding and recall processes.29 This test is widely used to assess memory deficits in different neurological diseases, including Alzheimer disease,30–32 temporal lobe epilepsy,33 and other syndromes including post-traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, and depression.34–36 The test was designed by Buschke et al. in the early 1970s37,38 when it was known as the Selective Reminding Test (SRT). Researchers subsequently developed multiple versions of the test.6,10 The FCSRT3 was presented as an improved version of the previous test since it included a cognitive processing test and fostered semantic processing during the learning process.

Several studies describe the influence of sociodemographic factors on test performance. Concerning age, some studies show that ageing causes a decrease in performance,17,39–41 except in the recognition scores, which remain the same in older patients. Based on these results, several studies describe the recognition task as a potential predictor of disease.39 Other studies, such as the Mayo Older American Normative Studies,42 have confirmed this effect on FCSRT test performance.

Regarding educational level, results obtained from different studies are contradictory. Some authors have found no significant education effects,42,43 while other authors report that this variable has a significant effect.17,39,40,44 Findings are similar for the variable ‘sex’. Some of the studies indicate that women score slightly higher,44–47 while other studies describe this variable as having a significant effect.17,40–42

Multiple normalisation studies in different languages provide data from this test, and they are included in several neurological examination textbooks. Such studies include those by Ivnik et al.42 and Grober et al.,48 both in elderly subjects. Several normative studies of Spanish-speaking subjects have been published recently. Campo et al. provided normative data for the SRT version39,49 and Labos et al. published normative data for the FCSRT from an Argentinean population, but they only included data for immediate recall. As for the entire test, including delayed recall, normative data for Spanish subjects aged 50 and older have been published within the context of the NN project.17

The main objective of the NEURONORMA project is to gather normative data from neuropsychological tests in adults aged 50 and older.50 An extension of the same project (NNy) has also been created for younger subjects. The aim of this project is to collect normative data from these tests in order to provide valid reference data for the Spanish population.51–56 Our article, within the framework of the project mentioned above, presents normative data from younger adult subjects (aged 18 to 49) for the ROCF and FCSRT tests.

Materials and methodsSubjectsRecruitment methods and sample characteristics have already been described in a previous article. To summarise, we recruited 179 subjects who had been educated in Spain and were either native Spanish speakers or bilinguals. Subjects were stratified by age and educational level. Subjects presented no cognitive disorders and met the following criteria: Mini-Mental State Examination57,58 ≥24 and Memory Impairment Screen59,60 ≥4.

Neuropsychological measurementsWe employed the neuropsychological protocol selected for use within the framework of the NN Project.50 All tests were administered according to the procedures published in their respective manuals.

Rey–Osterrieth Complex FigureParticipants were given a sheet of paper placed horizontally on the table. We followed the instructions described in the Meyers and Meyers manual.26 Participants were not allowed to rotate the piece of paper.

Scores were assigned according to the Meyers and Meyers criteria.26 Study variables are as follows: (a) copy accuracy: quality of the copy as a reflection of visuoconstructive ability; (b) copy time: time required to copy the figure; (c) immediate recall: accuracy of the figure after 3minutes; (d) delayed recall: accuracy of the figure after 30minutes, and (e) recognition of elements within the figure. Accuracy scores for the copy and recall tasks were calculated as the sum of correctly drawn elements. According to the scoring system, the figure contains 18 elements, each of which receives a score of 0.5, 1, or 2, depending on the accuracy, deformation, and location of each element. The highest possible score is 36 for each of the 3 tasks. The recognition trial was administered immediately after the delayed recall task. Subjects were shown a total of 24 elements and had to recognise the 12 that were included in the complex figure. The highest score for this task was 24 (the sum of all true positives and true negatives).

Free and Cued Selective Reminding TestBoth the current study and the NEURONORMA project use the same version of the test.50 Materials and instructions were provided by the author (Buschke's FCSRT. Copyright Albert Einstein College of Medicine of Yeshiva University, New York; items are not shown due to copyright restrictions). Stimuli were selected using the same criteria as those given in the English version of the test, although researchers did take the frequency and typicalness of the Spanish words into account.61 The test consisted of 3 immediate free recall trials, each of which was followed by a cued recall task and a 30-minute recall task (also free at first, then cued).

Each participant was shown a sequence of 4 cards (DIN-A4), each of which contained 4 words. Each word belonged to a different semantic category; the subject was asked to read each word aloud and state the semantic category for the words according to the semantic clue provided by the examiner. After the 16 items had been correctly identified, participants were asked to perform a non-semantic interference task lasting 20seconds (counting backwards by threes). Once they had finished, subjects were given a maximum of 90seconds to freely name the words they remembered, in any order. The task was interrupted if the subject was unable to recall any of the words during a 15-second interval. Following the free word recall, subjects were cued using the previously mentioned semantic clue for those words they were unable to recall spontaneously. This procedure was repeated 3 times. During the first 2 trials, if the subject was unable to recall the word with the help of the semantic clue, the examiner would state the word. Thirty minutes later, we performed the delayed recall trial. Here, the semantic clue was also provided when the subject was unable to recall the word spontaneously.

There were 5 study variables: (a) first-try free recall (maximum score: 16); (b) total free recall (sum of free recall items from all 3 trials; maximum score: 48); (c) total recall (sum of the total free recall and total cued recall items; maximum score: 48); (d) delayed free recall (maximum score: 16); (e) Delayed total recall (sum of delayed free recall and cued delayed recall items; maximum score: 16).

Statistical analysisA uniform statistical analysis was carried out in order to co-normalise all tests included in the project. The statistical analysis is described in greater detail in the article on methods used in NNy. A brief summary of the procedure is as follows: (a) the frequency distribution of raw scores was converted into Neuronorma scaled scores (NSS). To do so, we generated a cumulative frequency distribution. Raw scores were assigned percentile ranks according to their position within the distribution. Percentile ranks were then converted to scaled scores ranging from 2 to 18. This transformation of raw scores to NSS produced a normal distribution (mean±standard deviation: 10±3); (b) we defined the effects of sociodemographic variables by means of linear regressions. SS correlation coefficients (r) and coefficients of determination (R2) were determined for age, years of education, and sex for each of the study variables. (c) The NSS was adjusted for age, education, and sex according to the following formula: NSSA&E&S=NSS−(β1×[Age−35]+β2×[Education−13]+β3×Sex). Adjustments were only applied to the sociodemographic variables when the β coefficient was statistically significant and coefficients of determination were greater than 0.05. The regression coefficient (β) from this analysis was used as the basis for adjusting for sociodemographic factors in cases meeting these criteria. The resulting value was truncated to the next lower integer.

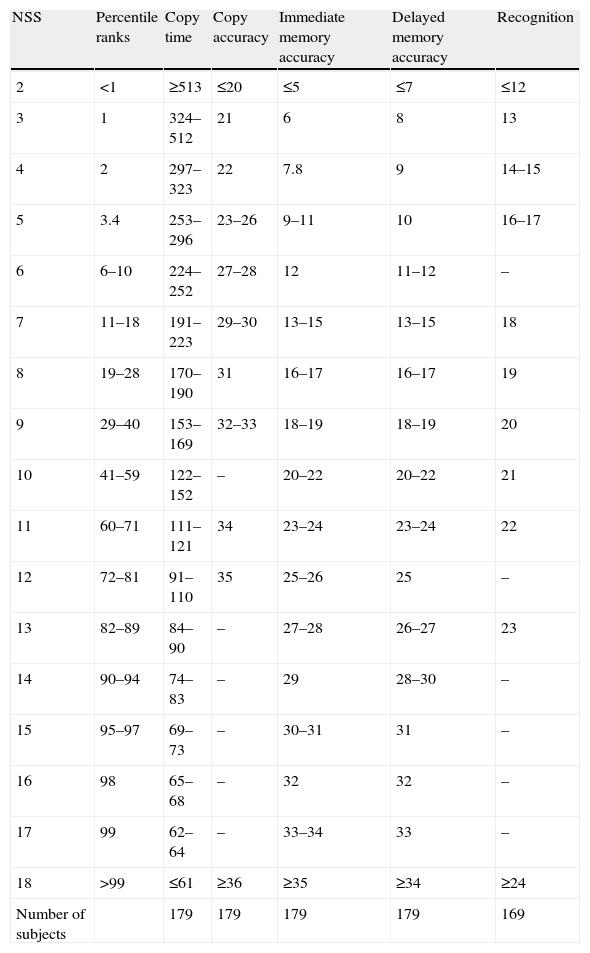

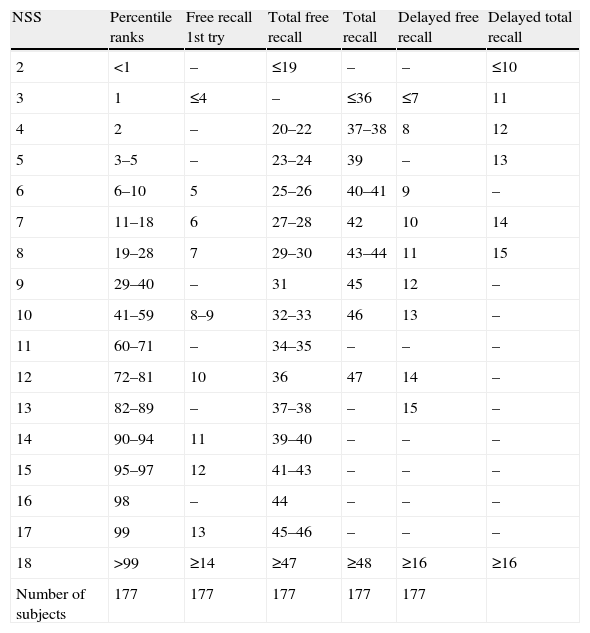

ResultsTable 1 displays the frequency distributions of raw scores from the ROCF test for the entire group aged 18 to 49, with the corresponding scaled scores and percentile ranks. Table 2 shows the same data from the FCSRT test.

Scaled and percentile scores on the ROCF test.

| NSS | Percentile ranks | Copy time | Copy accuracy | Immediate memory accuracy | Delayed memory accuracy | Recognition |

| 2 | <1 | ≥513 | ≤20 | ≤5 | ≤7 | ≤12 |

| 3 | 1 | 324–512 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 13 |

| 4 | 2 | 297–323 | 22 | 7.8 | 9 | 14–15 |

| 5 | 3.4 | 253–296 | 23–26 | 9–11 | 10 | 16–17 |

| 6 | 6–10 | 224–252 | 27–28 | 12 | 11–12 | – |

| 7 | 11–18 | 191–223 | 29–30 | 13–15 | 13–15 | 18 |

| 8 | 19–28 | 170–190 | 31 | 16–17 | 16–17 | 19 |

| 9 | 29–40 | 153–169 | 32–33 | 18–19 | 18–19 | 20 |

| 10 | 41–59 | 122–152 | – | 20–22 | 20–22 | 21 |

| 11 | 60–71 | 111–121 | 34 | 23–24 | 23–24 | 22 |

| 12 | 72–81 | 91–110 | 35 | 25–26 | 25 | – |

| 13 | 82–89 | 84–90 | – | 27–28 | 26–27 | 23 |

| 14 | 90–94 | 74–83 | – | 29 | 28–30 | – |

| 15 | 95–97 | 69–73 | – | 30–31 | 31 | – |

| 16 | 98 | 65–68 | – | 32 | 32 | – |

| 17 | 99 | 62–64 | – | 33–34 | 33 | – |

| 18 | >99 | ≤61 | ≥36 | ≥35 | ≥34 | ≥24 |

| Number of subjects | 179 | 179 | 179 | 179 | 169 |

NSS, Neuronorma scaled scores; ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure.

Scaled and percentile scores on the FCSRT test.

| NSS | Percentile ranks | Free recall 1st try | Total free recall | Total recall | Delayed free recall | Delayed total recall |

| 2 | <1 | – | ≤19 | – | – | ≤10 |

| 3 | 1 | ≤4 | – | ≤36 | ≤7 | 11 |

| 4 | 2 | – | 20–22 | 37–38 | 8 | 12 |

| 5 | 3–5 | – | 23–24 | 39 | – | 13 |

| 6 | 6–10 | 5 | 25–26 | 40–41 | 9 | – |

| 7 | 11–18 | 6 | 27–28 | 42 | 10 | 14 |

| 8 | 19–28 | 7 | 29–30 | 43–44 | 11 | 15 |

| 9 | 29–40 | – | 31 | 45 | 12 | – |

| 10 | 41–59 | 8–9 | 32–33 | 46 | 13 | – |

| 11 | 60–71 | – | 34–35 | – | – | – |

| 12 | 72–81 | 10 | 36 | 47 | 14 | – |

| 13 | 82–89 | – | 37–38 | – | 15 | – |

| 14 | 90–94 | 11 | 39–40 | – | – | – |

| 15 | 95–97 | 12 | 41–43 | – | – | – |

| 16 | 98 | – | 44 | – | – | – |

| 17 | 99 | 13 | 45–46 | – | – | – |

| 18 | >99 | ≥14 | ≥47 | ≥48 | ≥16 | ≥16 |

| Number of subjects | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 | 177 |

NSS, Neuronorma scaled scores; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

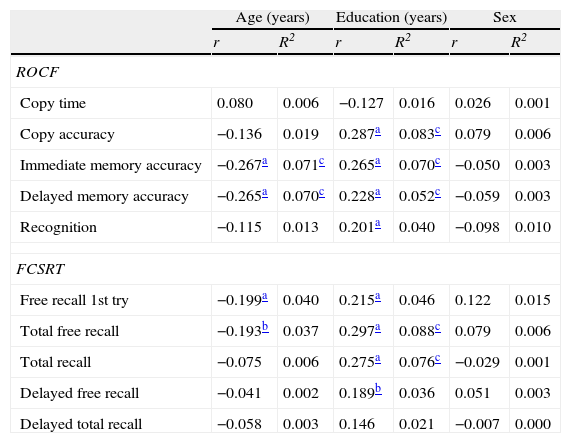

Table 3 shows correlation coefficients (r) and coefficients of determination (R2) between the NSS and the sociodemographic variables. We observed a significant age effect on immediate and delayed memory for the ROCF. In both cases, the explained variation was about 7%. Percentages of variance explained by education exceeded 5% for 3 variables: copy accuracy (8.3%), immediate memory (7%), and delayed memory (5.2%). No sex differences were observed for any of the ROCF variables. We found no significant age effects on any of the FCSRT variables. The education variable explained a significant percentage of both total free recall (8.8%) and total recall (7.6%). We observed no sex effects for any of the study variables.

Correlation coefficients (r) and coefficients of determination (R2) of the scaled scores by age, education, and sex.

| Age (years) | Education (years) | Sex | ||||

| r | R2 | r | R2 | r | R2 | |

| ROCF | ||||||

| Copy time | 0.080 | 0.006 | −0.127 | 0.016 | 0.026 | 0.001 |

| Copy accuracy | −0.136 | 0.019 | 0.287a | 0.083c | 0.079 | 0.006 |

| Immediate memory accuracy | −0.267a | 0.071c | 0.265a | 0.070c | −0.050 | 0.003 |

| Delayed memory accuracy | −0.265a | 0.070c | 0.228a | 0.052c | −0.059 | 0.003 |

| Recognition | −0.115 | 0.013 | 0.201a | 0.040 | −0.098 | 0.010 |

| FCSRT | ||||||

| Free recall 1st try | −0.199a | 0.040 | 0.215a | 0.046 | 0.122 | 0.015 |

| Total free recall | −0.193b | 0.037 | 0.297a | 0.088c | 0.079 | 0.006 |

| Total recall | −0.075 | 0.006 | 0.275a | 0.076c | −0.029 | 0.001 |

| Delayed free recall | −0.041 | 0.002 | 0.189b | 0.036 | 0.051 | 0.003 |

| Delayed total recall | −0.058 | 0.003 | 0.146 | 0.021 | −0.007 | 0.000 |

ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

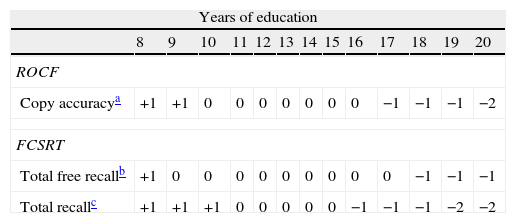

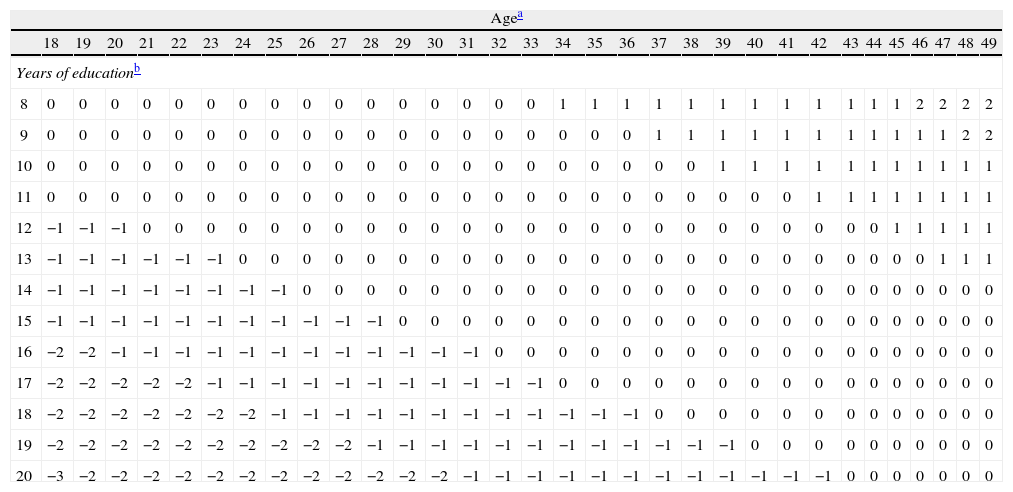

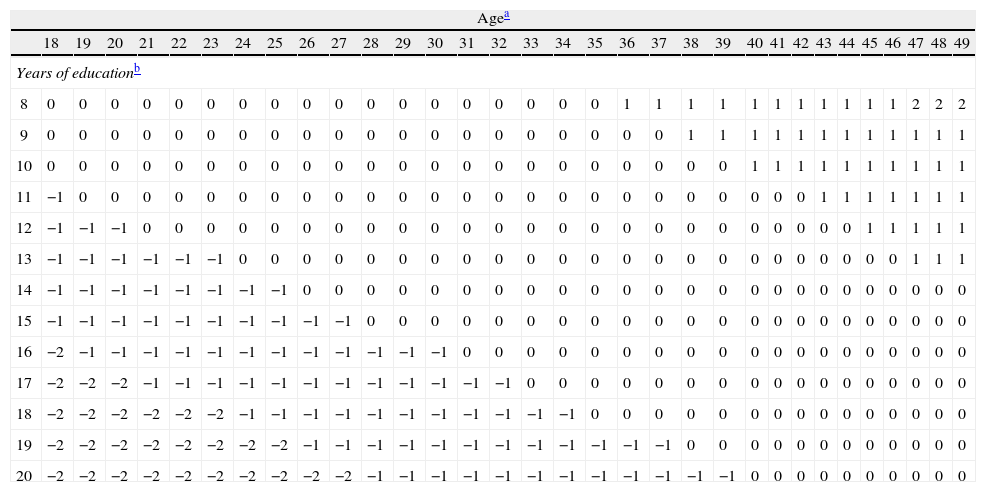

Table 4 displays education adjustments for those variables requiring adjustments for only that factor. Tables 5 and 6 (immediate and delayed memory, respectively) show age and education adjustments for those ROCF variables requiring adjustments for both factors. Table 4 is used by selecting the variable ‘years of education’ on the top row to view the correction to be applied to scaled scores obtained from Tables 1 and 2. Using Tables 5 and 6, we select age (top row) and years of education (left column) to obtain the adjustment.

Education adjustment table for the ROCF and FCSRT tests.

| Years of education | |||||||||||||

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | |

| ROCF | |||||||||||||

| Copy accuracya | +1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 |

| FCSRT | |||||||||||||

| Total free recallb | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 |

| Total recallc | +1 | +1 | +1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −2 | −2 |

ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure; FCSRT, Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test.

Age adjustment and education adjustment table for the ROCF test of immediate memory.

| Agea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | |

| Years of educationb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | −3 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure.

Age and education adjustment table for the ROCF test of delayed memory.

| Agea | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | 43 | 44 | 45 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 49 | |

| Years of educationb | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 12 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 14 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 17 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 19 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | −1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

ROCF, Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure.

Within the context of NEURONORMA young adults project (NNy), the current study provides normative data from the ROCF and FCSRT tests in younger Spanish adults. We should stress that these data were published at a time when there were no published reference data for the FCSRT test in younger Spanish adults. The current study shows the influence of sociodemographic variables on performance and provides adjustments for cases in which they are necessary.

Rey–Osterrieth Complex FigureResults suggest a slight education effect on 3 of the ROCF tasks (copy accuracy, immediate memory, and delayed memory). This finding coincides with those from previous studies.16,18,20 We observed a significant age effect on the memory variables, but not on the copying task. The effect of age on recall has been described in prior research.11,18 No significant sex effects were found for any of the study variables. Our results support prior evidence that concludes that there is no sex effect.7,16,22–25

Compared to results from the NN study of subjects aged 50 and older, findings are similar with respect to the effects of age on memory tasks. The age effect on the variable ‘copy time’ was the most relevant difference in older subjects. This may be attributed to the slowing effect associated with ageing. Education effect was similar between the two samples on the copy task and sex had no effect on the variables in either study.

Free and Cued Selective Reminding TestThe variable ‘years of education’ demonstrated a significant effect on 2 of the study variables (total free recall and total recall). The education effect has been described previously,39,44 although other studies, such as the one by Ivnik et al.,42 did not find that effect. Absence of the education effect can be explained by the test version, which presented drawings as stimuli. This procedure probably facilitated the recall task in subjects with lower educational levels.

Contrary to results from prior studies,39,41 we observed no significant age effect. These discrepancies may have been due to several factors. Firstly, the studies being compared use different versions of the test39,40,46 with different words and different clues (spoken clue). On the other hand, the studies include samples with different age ranges. An age effect has been described beginning at 60 years, which involves a decreased capacity for learning verbal stimuli. By the age of 70, the incidence rate is higher.40,46 Campo and Morales39 observed more marked differences between groups of the younger subjects (18–29 years) and the oldest group (50–59 years). The latter age range was not included in the current study. Our results coincide with those that found no sex-related differences,40,46 while some other studies did identify a sex effect.39,44–47

Compared with the NN study in subjects aged 50 and older,17 the current results pointing to an education effect and a minimal sex effect are very similar. However, we did detect differences in the age effect, which were probably due to the changes in verbal memory that occur with ageing. A joint analysis of both samples could help clarify this matter.

The current study provides normative data for the ROCF and FCSRT tests from young Spanish adults. Results corroborate the influence of education on some of the variables and point to a more moderate age effect, which only affected visual memory, and no sex effect. This study's main contribution is that it provides normative data of reference and tables for adjusting scores for sociodemographic variables.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Palomo R, et al. Estudios normativos españoles en población adulta joven (proyecto NEURONORMA jóvenes): normas para las pruebas Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure (copia y memoria) y Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test. Neurología. 2013;28:226–35.