To identify the attitudes of medical obstetrician-gynecologists (Ob-Gyn) and its association with the cesarean section rate.

Material and methodsWe performed a cross-sectional multicenter survey research, 197 Ob-Gyn were surveyed from eight hospitals, between November 2010 and May 2011. Data analysis included descriptive statistics on the general characteristics of Ob-Gyn, We used the χ2 test for bivariate analyses of categorical variables and logistic regression models to associate Ob-Gyn attitudes and percentage of births by cesarean section.

ResultsThe percentage of cesarean sections births expressed by Ob-Gyn surveyed was 59.2%. Ob-Gyn expressed a preference to delivery by cesarean section in 33.5%, 60.9% of the Ob-Gyn considered themselves skillful when attending cesarean deliveries compared against vaginal delivery. Thirty five percent of Ob-Gyn has scheduled a cesarean section for convenience, while 83.8% of Ob-Gyn said that women prefer cesarean births. In the regression model five variables are significantly associated with the Ob-Gyn that perform 30% or more of their cesarean deliveries, among these include: perception that vaginal are safer procedures than cesarean deliveries and that women have right to choose the type of delivery, whether vaginal or cesarean, with an OR=4.7 and 7.5 respectively.

ConclusionsWe have shown that attitudes of Ob-Gyn who are associated with cesarean section rate. These attitudes could be related with the increase of the cesarean births.

Identificar las actitudes de los obstetras-ginecólogos (Ob-Gyn) y su asociación con la tasa de cesáreas.

Material y métodosSe realizó una encuesta multicéntrica transversal a 197 Ob-Gyn procedentes de 8 hospitales, entre noviembre de 2010 y mayo de 2011. El análisis de los datos incluyó estadísticas descriptivas sobre las características generales de los Ob-Gyn. Utilizamos la prueba χ2 para análisis bivariados de variables categóricas, y modelos de regresión logística para asociar las actitudes de los Ob-Gyn y el porcentaje de nacimientos por cesárea.

ResultadosEl porcentaje de partos por cesárea expresados por los Ob-Gyn encuestados fue del 59,2%. Los Ob-Gyn expresaron una preferencia por el parto por cesárea en el 33,5% de los casos. El 60,9% de los Ob-Gyn se consideraron hábiles cuando asistían a partos por cesárea en comparación con el parto vaginal. El35% de los Ob-Gyn ha programado una cesárea por conveniencia, mientras que el 83,8% de dichos facultativos manifestó que las mujeres prefieren los nacimientos por cesárea. En el modelo de regresión, 5 variables se asociaron significativamente con los Ob-Gyn que realizan el 30% o más de sus partos por cesárea, entre ellas: percepción de que los procedimientos vaginales son más seguros que los partos por cesárea y que las mujeres tienen derecho a elegir el tipo de parto, ya sea vaginal o cesárea, con un OR=4,7 y 7,5, respectivamente.

ConclusionesHemos demostrado las actitudes de los Ob-Gyn que están asociadas con la tasa de cesárea. Estas actitudes podrían estar relacionadas con el aumento en los nacimientos por cesárea.

Cesarean section is the most common abdominal operation in women worldwide; the percentage of this practice varies widely between and within countries.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) at 1985, proposed that the percentage of Cesarean sections should not exceed 15% of total births, and concluded that statistically there are no additional health benefits above this percentage.2 Cesarean section rates have increased dramatically in several developing countries, especially in Latin America,3 it was estimated that, in different countries, the percentage of cesarean sections performed unnecessarily was between 16 and 47%.4 Also, is documented that women who have cesarean section without medical indication are at high risk of related complications or death.5

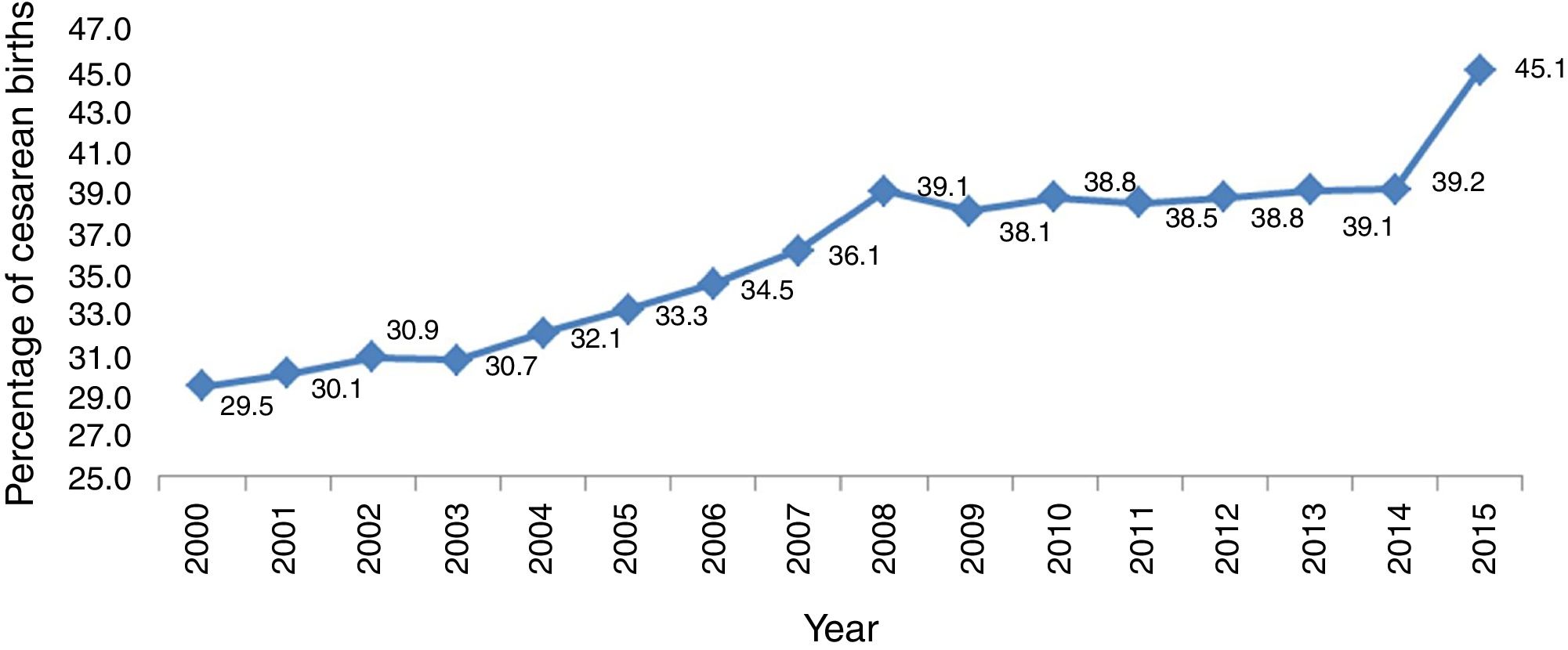

In Mexico, the percentage of cesarean increases each year,6 at 1985 Narro et al. found that the percentage of births by cesarean sections in four hospitals in Mexico City varied between 8 and 24%, with an average of 17%.7 In subsequent studies, the same authors reported that in 2005 the average cesarean section had increased in these same hospitals reaching an average of 33.6% in 2002.7 By 2010 it was estimated that the percentage of births by cesarean section and reached 38.8% nationally (Fig. 1); however the percentage of Cesarean sections varies between health institutions, for example, the Mexican Institute for Social Security (IMSS) reported for the same year 49.6% of pregnancies attended by cesarean section and Institute for Social Security and Services for State Workers (ISSSTE) 68.6% cesarean.9 During 2012 Mexico ranks fourth with the largest number of unnecessary cesareans.9

Several studies conclude that the increase in cesarean births associated with factors like Maternal characteristics such as age11 or pre-existing conditions, such as hypertension and obesity,12,13 saving time for physicians,14 maternal request cesarean section, or monitoring of labor by electronic means.8–15

For several years it has been documented that Cesarean sections account for increased service cost and risk to the health of the mother and the new born.8

An increasing percentage of Cesarean births were explained by medical reasons as are complications of pregnancy16; however at present these reasons do not explain the total growth in cesarean sections.17 In Nova Scotia, Canada, it was only able to explain 2.7% of the increase in cesarean sections on medical grounds from 1988 to 2000.4 Various studies suggest that at present the increase in cesarean sections is explained by non-medical indications for cesarean section.18,19 In this paper, the relationship between the attitudes of obstetrician-gynecologists (Ob-Gyn) on Cesarean births attended and the percentage of births by cesarean section performed in their institutions was analyzed.

Material and methodsA cross-sectional study was conducted by multicenter research survey, the study group was Ob-Gyn Hospital in Public Institutions in general hospitals (medical unit that has the four basic medical specialties of medicine) and specialty hospitals (conformed by one or several medical specialties), at Mexico City (8 hospitals). The survey was carried out between November 2010 and May 2011 in gynecology and obstetrics and gynecology-obstetrics medical residents.

A convenience sample of Ob-Gyn was performed. All Ob-Gyn were invited to participate all the participants provided written informed consent and completed a standardized questionnaire. The formula for n cross-sectional studies with infinite population was used the following criteria to estimate the sample size of the medical doctors interviewed: 95% confidence level, exposure estimated 13.6% share; bringing a sample size of 181 Ob-Gyn it was obtained.

A measuring instrument was developed from the literature review of studies on cesareans in different countries.20,21 The questionnaire was validated through a pilot test.22 The questionnaire measured four dimensions, “demographics”, “physician preference to the route of obstetric resolution”, “attitudes doctor about cesarean sections without medical indication” and “opinions concerning the right of women to say the kind of birth”.

The questionnaire was anonymously self-filling by participants.

The average cesarean rate was calculated by number of cesarean section performed divided by the number of total Births attended reported by each physician interviewed in the last month.

The data analysis included descriptive statistics on the general characteristics of Ob-Gyn in the study sample. Subsequently, bivariate analyses between variables related to the perception of physicians on the caesarean section with contingency tables were performed. We used the χ2 test for bivariate analyses of categorical variables; for this the probability of making the Type I error at 0.05 and partnerships sought as a measure taking the odds ratio (OR) between different variables studied with doctors who perform 30% or more of their cesarean deliveries was fixed. (The percent of cesarean deliveries recorded in 2009 in Mexico City was 30.5%.23) Finally multivariate models were estimated by relating the opinions of Ob-Gyn with the prevalence of cesarean sections in their hospitals through logistic regression technique. These analyzes were performed using SPSS version 16.

ResultsDuring the study period 197 were surveyed Ob-Gyn, the average monthly births attended by physicians was 18.9 births, the average cesarean rate was 59.2%. The median age in years of the interviewed physicians was 35.3 (23–61), with modal age of 30 years. However, there is a difference of means of age between sex, where the women were younger than the men (33 versus 38 years). The 79.2% (156) of the physicians surveyed, refer solve at least 30% of pregnancies by cesarean section. In Table 1 We described the Ob-Gyn characteristics of participants in the study were presented. We could see that a little over 30% were resident physicians, 33% had a history of having children cared for by cesarean and 48% had medical private practice (Table 1).

Socio-demographic and professional characteristics of responding obstetricians.

| Variable | Measurement | Frequency | Percentage % | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 103 | 52 | 0.521 |

| Female | 94 | 48 | ||

| Age | 23–29 years | 58 | 29.4 | 0.000 |

| 30–39 years | 92 | 46.7 | ||

| 40–49 years | 26 | 13.2 | ||

| 50–59 years | 13 | 6.6 | ||

| 60 or more years | 8 | 4.1 | ||

| Civil status | Single | 79 | 40 | 0.000 |

| Married | 85 | 43 | ||

| Free Union | 21 | 11 | ||

| Widower | 0 | 0 | ||

| Divorced | 12 | 6 | ||

| Length of experience in obstetrics | 0–9 years | 146 | 74.1 | 0.000 |

| 10 or more years | 51 | 25.9 | ||

| Full-time work in the hospital | Yes | 78 | 39.6 | 0.003 |

| No | 119 | 60.4 | ||

| Having had children | Yes | 92 | 46.7 | 0.354 |

| No | 105 | 53.3 | ||

| Antecedent of a son born by cesarean | Yes | 59 | 29.9 | 0.000 |

| No | 138 | 70.1 | ||

| Medical resident of Ob-Gyn | Yes | 60 | 31 | 0.000 |

| No | 137 | 70 | ||

| Private practice activity | Yes | 95 | 48 | 0.618 |

| No | 102 | 52 | ||

Regarding the choice of cesarean section, 33.5% of doctors said that resolving pregnancy, prefer to do it through a cesarean; 60.9% of physicians is considered more skillful response that cesarean births vaginally (Table 2).

Attitudes Ob-Gyn with cesareans.

| Variable | Measurement | Frequency | Percentage | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference of attending pregnancy resolution … | Vaginally | 95 | 48.2 | 0.000 |

| Abdominally | 66 | 33.5 | ||

| Both equally | 36 | 18.3 | ||

| According to your abilities by what type of pregnancy resolution you consider you are more skillful … | Vaginally | 43 | 21.8 | 0.000 |

| Abdominally | 120 | 60.9 | ||

| Both equally | 34 | 17.3 | ||

With regard to the opinions on the relevance of management cesarean delivery, 54.8% of Ob-Gyn considered that the percentage of vaginal births nationally is low, while 13.2% considered to be high; 73.1% agree that vaginal births are safer than C-sections, but the 41.6% of a normal pregnancy to term preferred partner for a cesarean; 73.1% think that more sections are performed in private hospitals for economic benefit to the doctor and found that 66.5% pregnancy resolution cesarean is fashionable today.

As for the regulatory aspects of cesarean section, 57.4% of physicians considered that 15% of births should be resolved by cesarean; 61.9% agree with the decision to perform a cesarean section should be based solely on the clinical; however, 35.0% of gynecologists said that has scheduled a cesarean for convenience; 55.8% agree to perform elective cesarean section for maternal request, is performed for fear of a lawsuit and 83.8% believe that today, women prefer cesarean births; 82.7% believe that women have the right to choose the type of delivery, either vaginal or cesarean.

As for the reasons to perform a cesarean section, 17.3% prefer to perform cesarean sections for saving time; 54.3% believe that cesarean sections without medical indication increases fetal morbidity; and 60.9% agree that cesarean sections without medical indication increases maternal mortality.

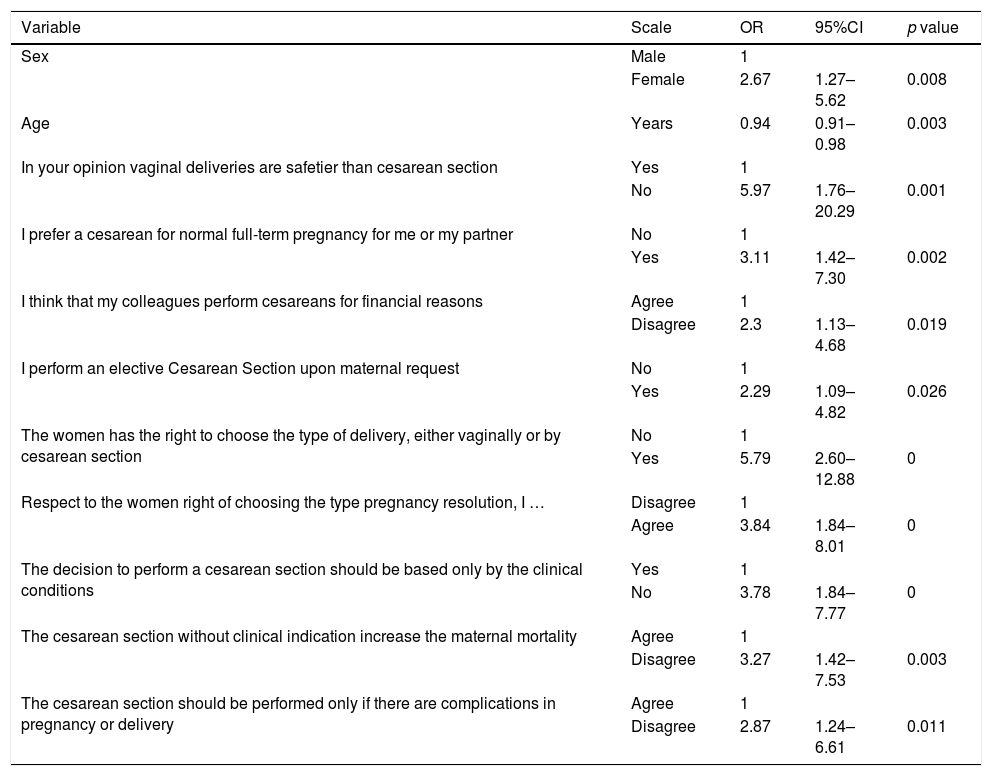

Bivariate analyzes were performed using as dependent variable Ob-Gyn who perform 30% or more of births by Cesarean serving (Table 3). The most significant association between cesarean section in 30% or more of births and Ob-Gyn attitudes regarding cesarean was the perception that vaginal births are safer than C-sections and procedures with the view that the women have the right to choose the type of delivery either vaginally or by cesarean section, with 5.97 and 5.79 respectively odds ratios.

Personal attitudes regarding cesarean section in relation of obstetricians who perform ≥30% of their cesarean deliveries.

| Variable | Scale | OR | 95%CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 2.67 | 1.27–5.62 | 0.008 | |

| Age | Years | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.003 |

| In your opinion vaginal deliveries are safetier than cesarean section | Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 5.97 | 1.76–20.29 | 0.001 | |

| I prefer a cesarean for normal full-term pregnancy for me or my partner | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 3.11 | 1.42–7.30 | 0.002 | |

| I think that my colleagues perform cesareans for financial reasons | Agree | 1 | ||

| Disagree | 2.3 | 1.13–4.68 | 0.019 | |

| I perform an elective Cesarean Section upon maternal request | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 2.29 | 1.09–4.82 | 0.026 | |

| The women has the right to choose the type of delivery, either vaginally or by cesarean section | No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 5.79 | 2.60–12.88 | 0 | |

| Respect to the women right of choosing the type pregnancy resolution, I … | Disagree | 1 | ||

| Agree | 3.84 | 1.84–8.01 | 0 | |

| The decision to perform a cesarean section should be based only by the clinical conditions | Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 3.78 | 1.84–7.77 | 0 | |

| The cesarean section without clinical indication increase the maternal mortality | Agree | 1 | ||

| Disagree | 3.27 | 1.42–7.53 | 0.003 | |

| The cesarean section should be performed only if there are complications in pregnancy or delivery | Agree | 1 | ||

| Disagree | 2.87 | 1.24–6.61 | 0.011 |

95%CI: confidence interval.

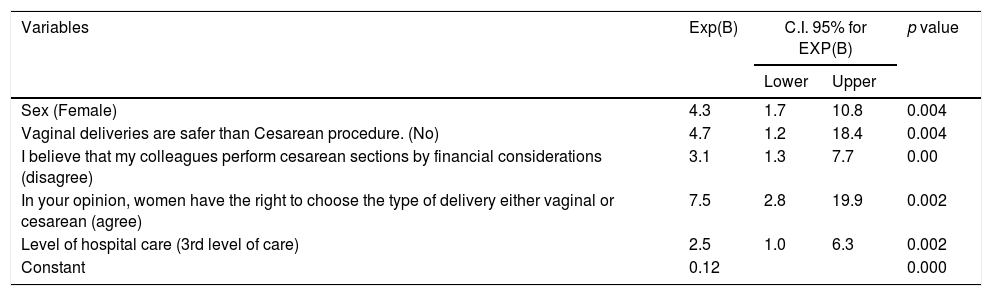

Finally it is presented in Table 4 the logistic regression model the best fit, where we see that the pattern is replicated, although five variables are significantly associated with the Ob-Gyn that perform 30% or more of their cesarean deliveries, the most important variables is the perception that vaginal births are safer than cesarean procedures and the view that women have the right to choose the type of delivery either vaginally or by cesarean section, with 4.76 and 7.51 odds ratio adjusted for variables sex, I believe that my colleagues perform cesarean sections by financial considerations (disagree), and level of hospital care (3rd level of care).

Multivariate analysis, obstetricians performing 30% or more of their cesarean deliveries.

| Variables | Exp(B) | C.I. 95% for EXP(B) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Sex (Female) | 4.3 | 1.7 | 10.8 | 0.004 |

| Vaginal deliveries are safer than Cesarean procedure. (No) | 4.7 | 1.2 | 18.4 | 0.004 |

| I believe that my colleagues perform cesarean sections by financial considerations (disagree) | 3.1 | 1.3 | 7.7 | 0.00 |

| In your opinion, women have the right to choose the type of delivery either vaginal or cesarean (agree) | 7.5 | 2.8 | 19.9 | 0.002 |

| Level of hospital care (3rd level of care) | 2.5 | 1.0 | 6.3 | 0.002 |

| Constant | 0.12 | 0.000 | ||

95%CI: confidence interval.

As has been reported in other studies, female physicians reported higher cesarean rates, this is consistent with the findings of Sjur Lehmann et al.,24 who conducted the study in a Norwegian population, they found that female doctors and midwives had higher cesarean rates, compared with men between 1969 and 1998. In our study we found an association of 4.65 times in women doing 30% or more of their cesarean deliveries, compared to men. Regarding the age of the attending physician and its association with the percentage of cesarean sections, in this study an inverse relation, to younger age, a higher percentage of cesareans performed by physicians; However, this variable is strongly correlated (90%) with years of clinical practice, so that a greater number of years of clinical practice decreases the number of cesarean performed.

Cesarean sections on programming for convenience and significant time savings,25 in this study we found that 35% of physicians surveyed are scheduled cesareans for convenience and 17.3% of all physicians prefer a cesarean section for saving time, it noted that these two factors were not significantly associated with performing 30% or more of cesarean rate, but with private practice, there is a risk of 2.4 times (CI 1.32–4.41) with a private practice doctor schedule a cesarean section compared to Ob-Gyn who they did not have private practice.

The economic impact has been a reason why it is believed to have increased cesarean deliveries,5 this study found an association between the percentage of Cesarean sections and Ob-Gyn who disagree with this premise, Ob-Gyn who disagree with that cesarean sections are performed by financial issues, made 2.11 times more cesarean sections compared with those who agree. In addition, Ob-Gyn who have private practice disagree with this argument (1.79, 95%CI 1.02–3.16) than those without private practice.

It is shown that induction of labor increases by 70% the complications of childbirth and pregnancy favors abdominally26,27; however, we found that only 20.3% of Ob-Gyn agree with the premise.

Perform a cesarean section on maternal request, worldwide studies28–31 conclude that between 29% and 84.5% of doctors agree or are willing to perform a cesarean section, this study found that this proportion is 44.2% and these Ob-Gyn perform cesarean sections 2.3 times (95%CI 1.13–4.68) compared to those who are not willing to perform a cesarean section for maternal request; however 24% of Ob-Gyn advise a cesarean section to her daughter with normal pregnancy, a proportion that is consistent with the published internationally (7–46%).

According to international literature, a rate of increase in Cesarean births is explained by medical reasons (complications of pregnancy), but this does not explain why the total growth in the cesarean rate (only 2.7%) in this study It showed that 63.5% of Ob-Gyn agree that there are currently more pregnancy complications, so has increased the percentage of births by cesarean.

The increase in cesarean sections also explained for non-medical indications, this study found that 38.1% of physicians disagree with the decision to perform a cesarean section should be based exclusively on the clinical, besides these Ob-Gyn perform 3.78 (95%CI 1.84–7.77) times more cesareans than those agree.

The perceived risk of Ob-Gyn with complaints and litigation associated with the fulfillment of a cesarean section for maternal request,32 the study found that 22.8% of Ob-Gyn would perform a cesarean section for maternal request for fear of a lawsuit.

Preferences of consumers and professionals influence the mode of delivery, the study is found that 33.5% of Ob-Gyn prefer to perform cesarean They also said that 83.8% of women prefer cesarean births, and 66.5% think births by caesarean section are hot.

It is important to discuss strategy for better obstetric practice because, as stated by several authors, the increase in cesarean sections that have no clinical justification and exposes mother and the new born to unnecessary risks and raises the costs of health care.6–8

Reducing cesarean in the world is a complex and difficult task that must be addressed on several fronts and using various strategies.33

As Narro and colleagues said, it is urgent to implement a program to reduce the frequency of cesarean sections, must foster care for normal deliveries general and family practitioners, and undertake a program to raise awareness of the risks and costs of cesarean directed the general population.8

The percentage of Cesarean births can be reduced safely34–35 since they are not necessarily associated only with demographic, clinical, or fetal factors. Certain individual characteristics of obstetricians as the commitment to reducing facilitate decrease in cesarean deliveries.36

The limitations of the study were in the type of non-probabilistic sampling, the influence of possible age and sex bias among female Ob-Gyn; Coupled with the failure to include the evaluation of age and comorbidities or other clinical conditions of the patients that influence the decision making to perform a cesarean delivery. But beyond these, he brought the urgency of controlling the rate of cesarean sections our country. There are reasons other than medical necessities that might explain the high rate of cesarean section in this study: (1) So the sex of the treating physician seems to influence the decision making of the woman on the form of resolution of the pregnancy; because they believe that cesarean section is safer, faster, and less painful; by values and perceptions of some women (patient and Ob-Gyn) wrongly believe that they are more likely to regain their pregnancy shape after cesarean section than vaginal birth (recalling that the mean age among women Ob-Gyn was lower than in men); (2) some Ob-Gyn do recommend cesarean section to women in view of the present uneasy doctor–patient relationship and possible lawsuits; (3) cesarean section is financially profit table for the hospital. Likewise, the study indirectly reveals the contradictions and reality of the human condition between what is established in a clinical practice guide and the value judgments of the treating Ob-Gyn and the relationship with the woman; that to know the context and the circumstances, another type of qualitative studies is required.

In order to reduce the rate of Cesarean sections, policies, and procedures agreed by the service providers of obstetrics protocols they should be rigorously followed by the medical and nursing staff.37 According to other authors, efforts to reduce the Cesarean section should focus on the areas of fetal distress, cephalopelvic disproportion, and repeat cesarean for diagnosis of previous cesarean section.38

It will be necessary to establish a broad call within the medical profession that can stop what so far maintained a sustained growth. There are examples in our country of these efforts; the Civil Hospital of Guadalajara decreased the percentage of Cesarean sections 28–13% within five years.39 This reduction was benefit in reducing neonatal mortality and is a role model in the country.

In order to reduce the number of unjustified cesareans, it is necessary to design, implement and evaluate public health policies focused on an individualized public health of the patients, to change the models of antenatal care is recommended as a strategy to overcome this difficulty therefore empowering women to make a meaningful choice in which the woman's reasoned and informed decision. This also includes not only applicable to the staff of the medical units, but is recommended from university training as a doctor undergraduate and postgraduate courses (in our study 30% were resident physicians) and also the need to investigate the relationship between cesarean sections and perceptions and desires of mothers.

ConclusionsThey are dominant attitudes of physicians who were associated with the number of cesarean rate; these attitudes could be related with the increase of the cesarean births.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.