Papillary endothelial hyperplasia (PEH) or Masson's tumor is a rare benign vascular tumor that usually appears in the soft tissues of the head and neck, trunk and extremities, being extremely rare in the breast. Its diagnosis can be a challenge, especially in the follow-up of patients with previous disease of breast carcinoma. We present the case of a 65-year-old patient, with a history of bilateral breast cancer and reconstruction with implants, who presented a Masson's tumor during follow-up. An ultrasound scan was performed, showing a well-circumscribed mass in the left breast, located in the posterior contour of the implant. Subsequently, magnetic resonance imaging (MR) depicted an enhancing tumor, without infiltration of adjacent structures. Finally, the definitive anatomopathological diagnosis was obtained after surgical excision.

La hiperplasia papilar endotelial (HPE) o tumor de Masson es un tumor vascular benigno poco frecuente, que suele aparecer en las partes blandas de la cabeza y el cuello, tronco y extremidades, siendo excepcional la localización en la mama. Su diagnóstico puede ser un reto, especialmente en el seguimiento de pacientes oncológicos. Presentamos el caso de una paciente de 65 años, con antecedente de cáncer de mama bilateral y reconstrucción con prótesis, que presentó un tumor de Masson en una revisión. Se realizó una ecografía donde se visualizó en la mama izquierda una masa de bordes bien delimitados, localizada en el contorno posterior de la prótesis. Se completó el estudio con resonancia magnética (RM) que mostró un realce intenso del tumor, sin invasión de estructuras vecinas. Tras la intervención quirúrgica se obtuvo el diagnóstico anatomopatológico definitivo.

Papillary endothelial hyperplasia (PEH) or Masson’s tumour is a benign vascular lesion, first described by Masson as a “hemangioendotheliome vegetant intravasculaire” in 1923.1 It is usually located in the skin and soft tissues of the head and neck, trunk and extremities; in rare cases it presents in the breast. Given the rarity of the latter, it is not often included in the differential diagnosis of breast pathology.2

We present a case of PEH in a patient with a history of bilateral breast carcinoma treated with mastectomy, immediate reconstruction with prosthesis and adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Clinical caseSixty-five-year-old woman, with a history of bilateral subcutaneous mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with prepectoral prostheses in 2007, for a bilateral multicentric lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

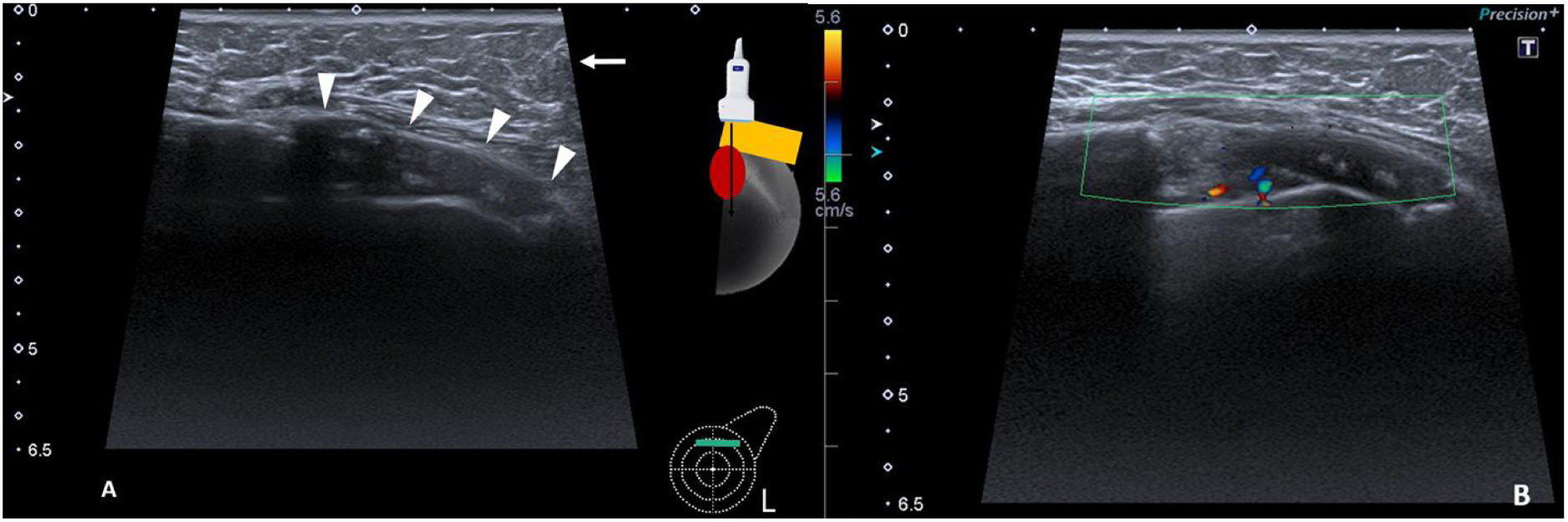

The patient attended the breast radiology department on a scheduled basis for annual check-ups. At this last check-up, the ultrasound study showed a new hypoechoic, well-defined solid mass in the left breast, measuring 4 cm. It was located in the upper quadrants between the cover and the prosthetic capsule. There were no signs of infiltration into the surrounding structures; it was categorised as BI-RADS 4a (Fig. 1) and a breast MRI was performed (Figs. 2 and 3).

Ultrasound image of the upper quadrants of the left breast and colour Doppler. (A) A circumscribed, oval, hypoechoic solid mass, with a maximum diameter of 4 cm was identified corresponding to the fibrous capsule (arrowheads). In the anterior plane subcutaneous fat was observed (arrow). (B) The lesion demonstrates a mild Doppler colour signal uptake.

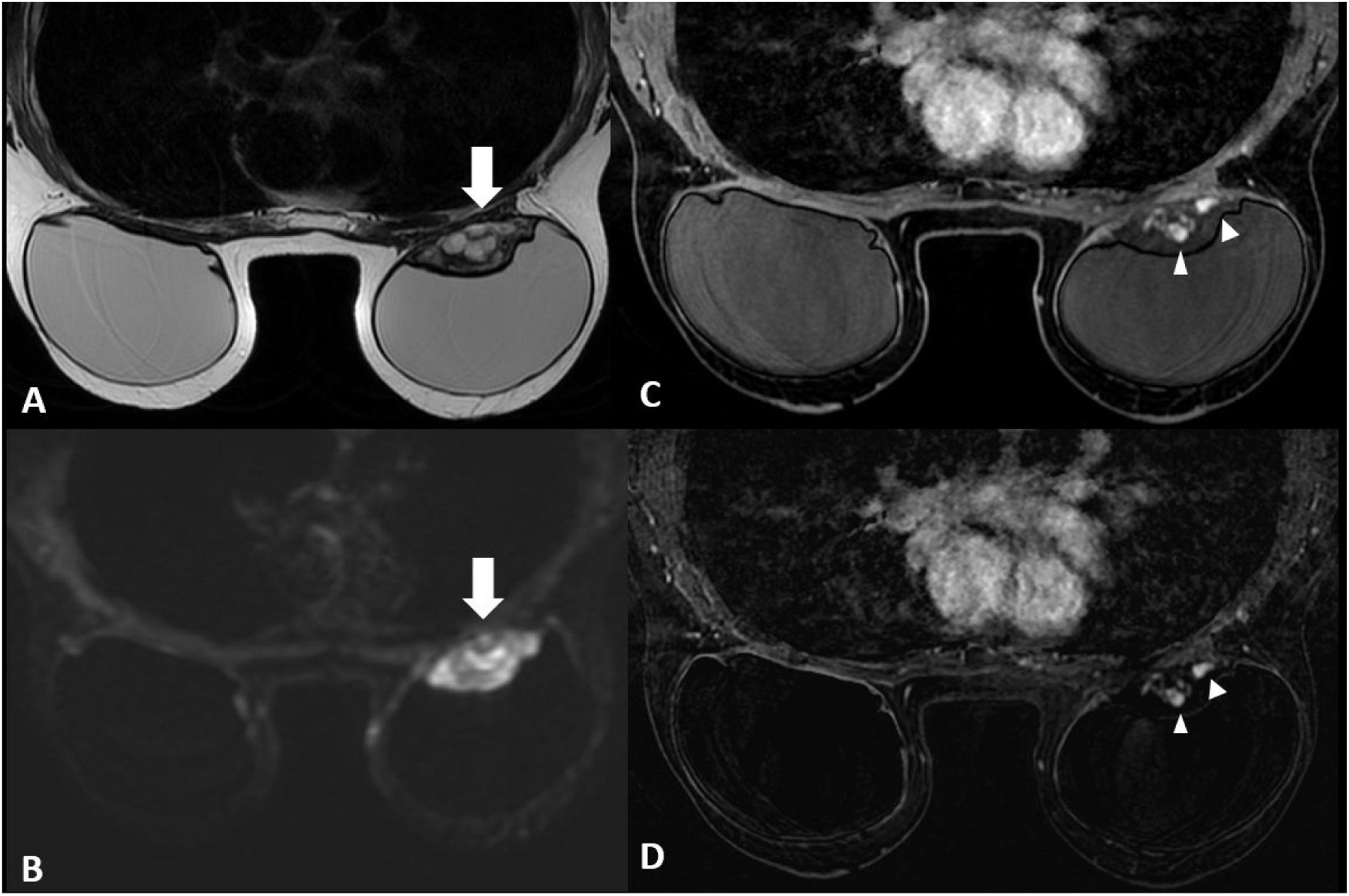

MRI images of the breast. (A) T2-weighted sequences The mass (arrow) presented with circumscribed borders, with a predominantly hyperintense heterogenous signal, located in the posterior region of the breast prosthesis. (B) Diffusion sequence, in which marked restriction was observed within the lesion (arrow). (C, D) T1-weighted sequence following the administration of intravenous contrast (gadolinium) and a post-contrast subtraction image. Early and intense enhancement was observed, with peripheral and serpiginous nodular morphology within the lesion (arrowheads). No noteworthy abnormalities were identified in the right breast.

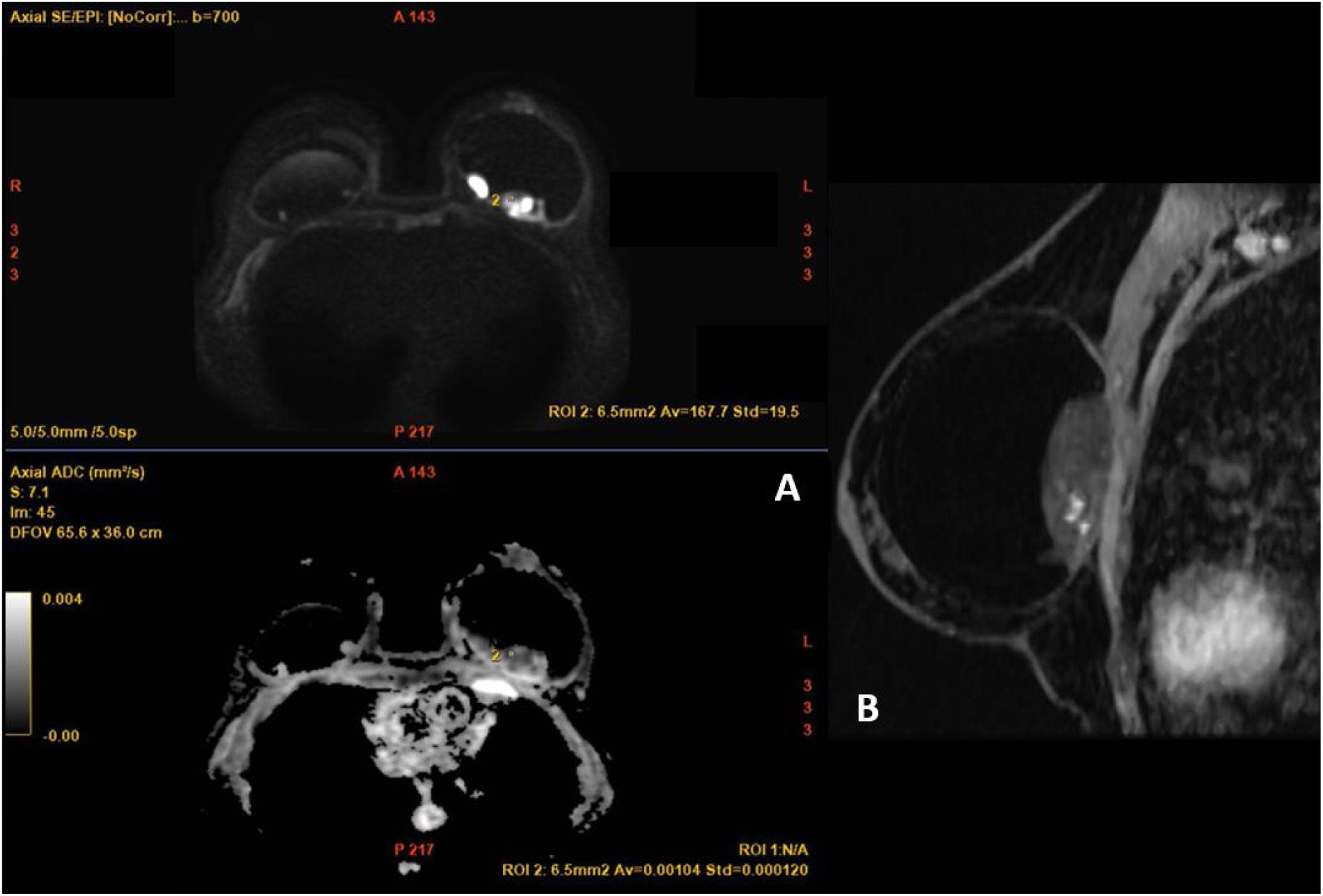

With these findings, the differential diagnosis made it necessary to rule out atypical anaplastic large cell lymphoma. The Tumour and Breast Pathology Committee planned the removal of the breast implants and ordered the pathological study of the lesion (Fig. 4), which reported a tumour affecting the prosthetic capsule, composed of a proliferation of vascular channels and papillary projections lined by endothelium. We did not observe atypia or other neoplastic signs, typifying the lesion as PEH.

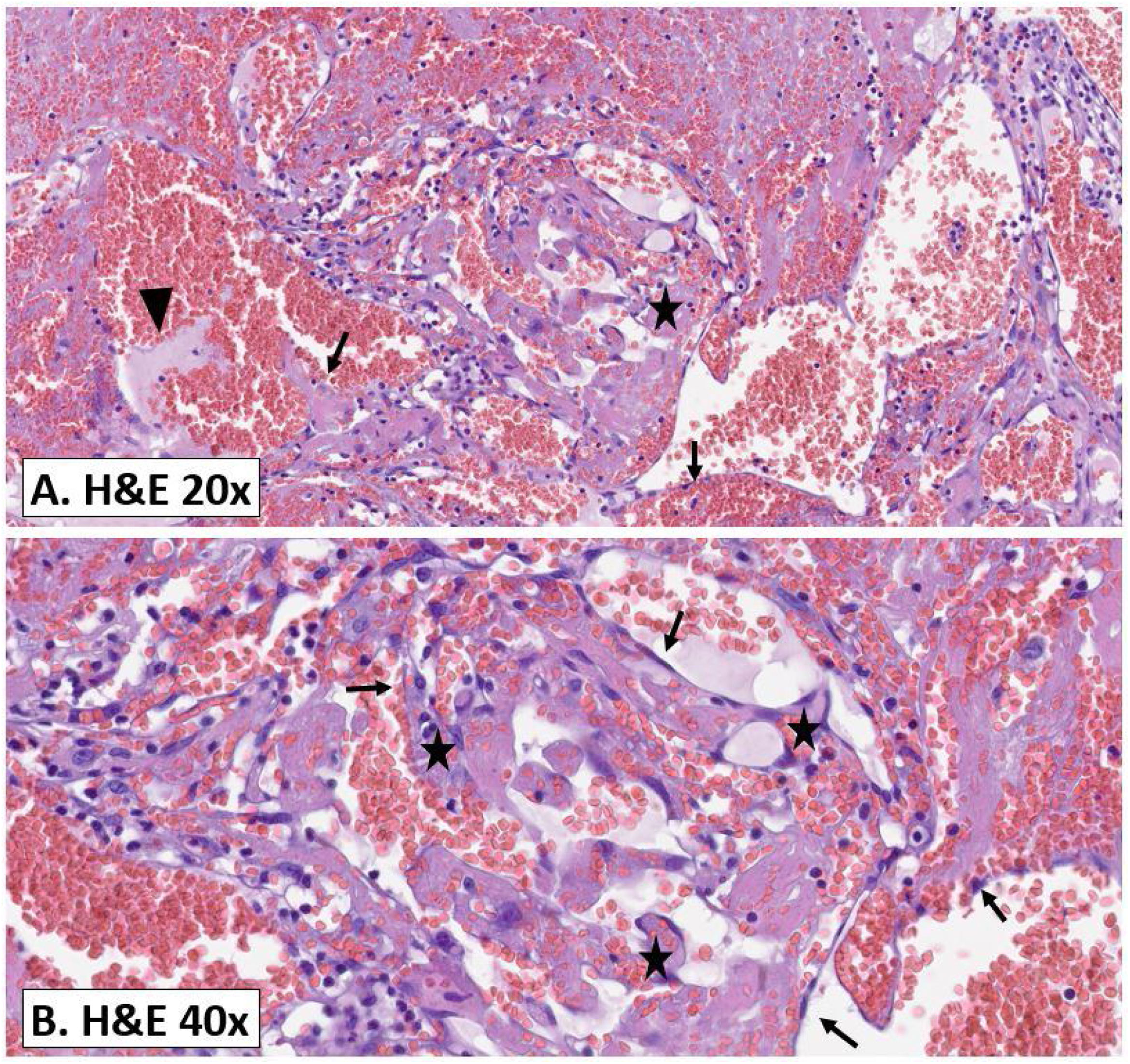

Pathology study. (A) Histological image of the surgical piece stained with haematoxylin and eosin, at 20× magnification. (B) Histological image with the same stain (H&E), at 40× magnification. A well-circumscribed vascular proliferation was observed (also called papillary endothelial hyperplasia [PEH]). Papillary structures of connective tissue (star), lined by a single layer of endothelial cells (arrow), proliferate within a vascular lumen. In Image A, a fibrin thrombus (arrowhead) can also be seen. These are evident in the early stages and in time are replaced with papillary structures of a benign appearance, characteristic of PEH and previously described.

PEH or Masson’s tumour is an infrequently occurring benign vascular lesion that on occasion involves the breast. The longest PEH series was published in 2003, with a total of 17 cases, collated over an interval of 20 years.2 The remaining publications found in our literature search include shorter case series3 or isolated cases,4–6 with the case we describe here being the first case of PEH diagnosed at our centre to date.

Masson’s tumour is more frequent in women around 60 years old3 and presents in imaging as a small nodule with circumscribed or lobulated margins, located mainly in the subcutaneous cellular tissue with no signs of invasion into surrounding structures,2,3 as in our case.

The histopathology describes a proliferation of one or two layers of endothelial cells forming papillary and pseudovascular structures, with no mitotic activity or atypia.2,3 The differential diagnosis in our clinical case included: recurrence of breast carcinoma, angiosarcoma, breast implant-associated large cell lymphoma and silicone granulomas.

Breast cancer Breast cancer is the first diagnosis to consider, given its frequency and our patient’s history. However, the probability of recurrence was low, given the histological and immunohistochemical profile of the previous carcinoma and the radical treatment applied.

Angiosarcoma Primary angiosarcoma is the most common malignant vascular tumour of the breast, with a peak incidence between 30 and 50 years, lower than PEH, which occurs at older ages,7 and has a latency period of 10 years when associated with radiotherapy.5 Furthermore, primary angiosarcoma is identified as a larger infiltrating mass with poorly defined borders, in contrast with the presentation of PEH which is a non-invasive, well-defined lesion, as in our case.5,7 On the other hand, PEH shares the papillary growth of vascular cells with angiosarcoma in the pathology study,2 and they are differentiated based on observing signs of infiltration, nuclear pleomorphism, mitosis, atypia and areas of necrosis.3

Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL) ALCL is linked to the fibrous capsule of the implant, without direct involvement of the breast parenchyma. It most commonly presents as a delayed periprosthetic seroma. In rare cases it manifests as a solid mass with circumscribed borders, but, unlike PEH, it is not hypervascular. Neither entity is usually associated with locoregional lymphadenopathy.8

Silicone granulomas. Silicone granulomas are nodules that originate between the cover and the fibrous capsule of the implant, due to an immune-mediated response to the prosthesis, without associated rupture. MRI is the diagnostic technique of choice, where an intracapsular mass with smooth margins is observed, presenting heterogeneous hypersignal in T2-weighted sequences, hyposignal in fat suppression sequences and late enhancement, with a type 1 curve,9 all findings that differ from PEH images.

In the literature review, only two cases of PEH published in the literature were found in patients with breast cancer and prostheses. These patients had received radiation therapy, speculating a possible correlation.4,6 Our case is exceptional, presenting the same clinical context but without associated treatment with radiotherapy, and the performance of the breast MRI has provided essential imaging information for the differential diagnosis.

Percutaneous biopsy was not possible due to the posterior location of the lesion. Some authors advise complete excision, due to the difficulty in differentiating between angiosarcoma and PEH on a histological level, especially in cases of low-grade angiosarcoma.2 In contrast, other authors, such as Guilbert et al.,3 diagnosed PEH by biopsy, which meant conservative treatment could be followed. We agree with these authors on the importance of adequately correlating clinical, imaging and pathological features in diagnosis.

ConclusionPEH of the breast is a rare entity, with non-specific imaging findings. Its differential diagnosis is a challenge, particularly in patients with a history of previous breast carcinoma. Finally, the imaging similarities with breast angiosarcoma should be noted.

Author contributionsResearch coordinators: GMOC, CGM, SCC, AAM.

Development of study concept: GMOC, CGM, SCC.

Study design: GMOC, CGM, SCC.

Data collection: GMOC.

Data analysis and interpretation: GMOC.

Literature search: GMOC, AAM.

Writing of article: GMOC, CGM, SCC, AAM.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

![Pathology study. (A) Histological image of the surgical piece stained with haematoxylin and eosin, at 20× magnification. (B) Histological image with the same stain (H&E), at 40× magnification. A well-circumscribed vascular proliferation was observed (also called papillary endothelial hyperplasia [PEH]). Papillary structures of connective tissue (star), lined by a single layer of endothelial cells (arrow), proliferate within a vascular lumen. In Image A, a fibrin thrombus (arrowhead) can also be seen. These are evident in the early stages and in time are replaced with papillary structures of a benign appearance, characteristic of PEH and previously described. Pathology study. (A) Histological image of the surgical piece stained with haematoxylin and eosin, at 20× magnification. (B) Histological image with the same stain (H&E), at 40× magnification. A well-circumscribed vascular proliferation was observed (also called papillary endothelial hyperplasia [PEH]). Papillary structures of connective tissue (star), lined by a single layer of endothelial cells (arrow), proliferate within a vascular lumen. In Image A, a fibrin thrombus (arrowhead) can also be seen. These are evident in the early stages and in time are replaced with papillary structures of a benign appearance, characteristic of PEH and previously described.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/0000006600000004/v1_202407310528/S2173510724000764/v1_202407310528/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)