This paper aims to describe our experience in an interventional radiology unit in a hospital in Spain that was severely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. To this end, we did a prospective observational study of 20 consecutive patients with COVID-19 who underwent 21 interventional radiology procedures between March 13, 2020 and May 11, 2020. We describe the measures taken to reorganize the work and protective measures, as well as the repercussions of the situation on our unit’s overall activity and activity in different phases. The COVID-19 pandemic has represented a challenge in our daily work, but learning from our own experience and the recommendations of the Spanish radiological societies (SERVEI and SERAM) has enabled us to adapt successfully. Our activity dropped only 22% compared to the same period in 2019.

El objetivo del presente trabajo es mostrar la experiencia en una unidad de radiología intervencionista de un hospital de nuestro país muy afectado por la pandemia Covid-19. Para ello se ha realizado un estudio observacional prospectivo de una serie de casos consecutivos (n = 20) de pacientes Covid-19, sometidos a 21 procedimientos intervencionistas, durante el periodo de 2 meses de estudio (13 marzo -11 mayo de 2020). Se exponen las medidas de re-organización del trabajo, medidas de protección; así como la repercusión de la situación en la actividad de la unidad total y por fases. La pandemia Covid-19 ha supuesto un reto para el trabajo diario en nuestra unidad, pero siguiendo nuestra propia experiencia y las recomendaciones de SERVEI y SERAM, nos hemos adaptado a la situación de forma exitosa. Se ha observado una disminución de la actividad de tan sólo un 22% sobre el mismo periodo del año 2019.

COVID-19, also known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), emerged in Wuhan, China, in late 2019, and since then has swiftly spread around the world. It reached the European continent in the month of February. Among the hardest-hit countries were Italy and Spain, with different repercussions by autonomous community, province and municipality.1

The autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha became the third most heavily impacted autonomous community in Spain, after Madrid and Catalonia, with 144 deaths per 100,000 habitants in the month of May. The first positive cases in this region were recorded in the first week of March.1

Against this backdrop, radiology departments, like all other hospital departments, had to adapt to a new, evolving situation, and received instructions from management to comply with a contingency plan. This plan could be summed up as suspending scheduled activities, expediting pending studies for admitted patients to facilitate discharge and exclusively attending to emergency, preferential and oncological pathology that could not be delayed, until further notice.

Essentially, chest radiology studies — studies using portable equipment, studies in emergency plain X-ray rooms and chest computed tomography scans — increased.

For other areas, such as interventional radiology (IR), angiography rooms were prepared to receive patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection through different entrance and exit circuits and different clean and dirty rooms.2–8 The first interventional procedures were performed in the week of 16 March and, from then on, up to the date of submission of this paper (11 May).

Ways of working changed, agendas were reorganised and measures were adopted to protect professionals. Measures for deep cleaning of facilities and equipment were also put in place.

Various articles from around the world on organising IR rooms and managing these patients have been published. Articles by Ierardi,2 Da Zhuang3 and Too4 reported the preventive measures established at those authors' respective hospitals. Other authors such as Zhu5 contributed numerical data on patients cared for when the incidence of the disease peaked in their region and compared them to the data recorded for the previous year.

The objective of this study is to share the impact that the pandemic has had on our IR room by describing the way in which the room is organised and comparing its activity to the same period in the previous year.

Reorganisation of angiography roomsPatient management during the pandemic was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and protocols established by the World Health Organization (WHO),6 the Spanish Ministry of Health and the different Spanish Regional Ministries of Health, as well as the recommendations for action described by the Sociedad Española de Radiología Vascular Intervencionista [Spanish Society of Vascular and Interventional Radiology] (SERVEI),7 the Sociedad Española de Radiología Médica [Spanish Society of Medical Radiology] (SERAM)8 and the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiological Society of Europe (CIRSE),9 among others.

First of all, given the novelty of the situation, it was essential to hold online orientation meetings on management of interventional radiology rooms, management of infected patients and prevention measures established, as well as rigorous training in these measures and availability of written protocols, especially in the initial stages of the pandemic.

The types of procedure performed during the state of alarm, in accordance with the advice of the hospital board, were emergency and oncological procedures which could not be delayed. Elective cases were postponed. Between 13 March and 11 May 2020, 398 procedures were performed in 397 patients in the hospital's IR unit.

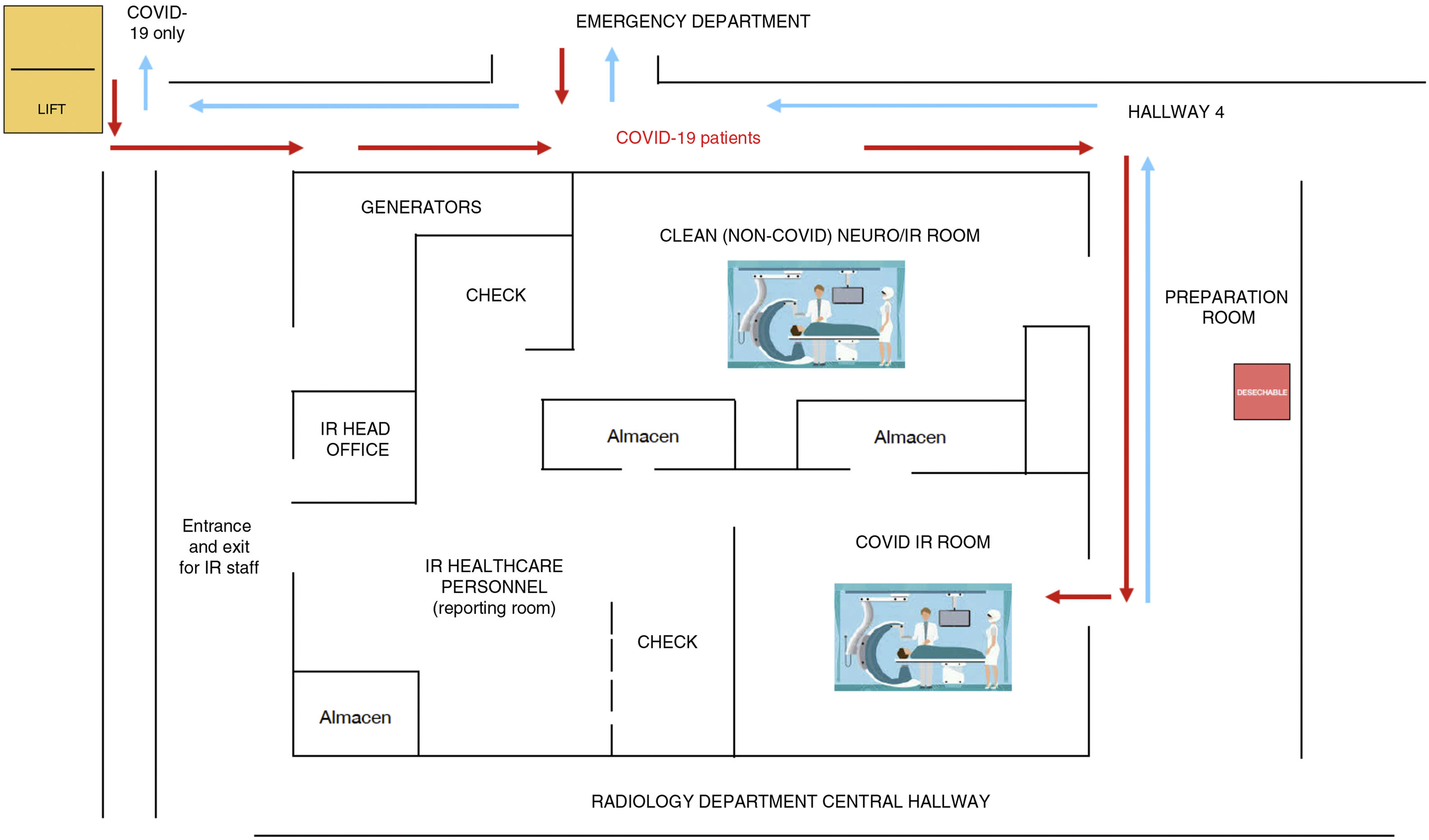

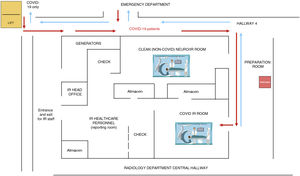

For the performance of these procedures, due to the high rate of infections transmitted by droplets and through contact with contaminated surfaces,10 patients had to be divided into groups in order to prevent new infections. Our department is equipped with two angiography rooms, which were used at medium to full capacity at the peak of the pandemic. To make proper use of these rooms, in accordance with recommendations, the interventional area was restructured to create two separate circuits: one for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and one for uninfected patients (Fig. 1). In all cases, apart from a neurointerventional emergency, all patients with COVID-19 were cared for in the latter location so as to prevent transmission and enable a deep cleaning of the room following the intervention.

The personal protective measures employed in the treatment of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 were hand washing, double gloving and wearing a waterproof gown, goggles or a face shield, a cap, an FFP2 mask (with a surgical mask on top of the FFP2 mask) and shoe covers (Fig. 2). All patients who received care wore a surgical mask.

Regarding the management of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 in interventional rooms, in all procedures the room was prepared before the patient arrived, both by bringing in the materials needed and by covering the equipment in plastic (Fig. 3). In addition, each team member knew in advance what his or her role would be during the procedure, such that only the essential staff (an interventional radiologist, a nurse and a technician), duly protected, were in the room, and the doors remained closed for the procedure's duration.

Once the procedure ended, to keep themselves free from contamination, the staff left the intervention room and proceeded to an adjacent room where they removed their protective equipment, discarded it in specific biohazard waste disposal containers and washed their hands in the appropriate manner. The patient was transferred back to his or her site of origin, without a surveillance period in the recovery room, in order to minimise exposure time.

Finally, the angiography room was cleaned, the materials used were discarded and non-disposable instruments were immersed in Adaspor®, an antiseptic, sporicidal solution, before being sterilised. In addition, patient volume permitting, a reasonable period of time was established for ensuring air exchange (2 h); after this time, properly protected cleaning staff went in to disinfect the room.

Study context/epidemiological dataIn accordance with the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Spain, and under the guidance of the WHO and the Spanish Ministry of Health, strategies for reorganising interventional procedures at our hospital were divided into two clearly differentiated phases.

In the first or contingency phase (Phase 1), from 13 March (the day before the central Spanish government declared a state of alarm) to 27 April, inclusive, a series of structural modifications were made and healthcare activities were reduced to the bare essentials (emergency, preferential and oncological activities), so as to achieve maximum control and prevention of disease transmission. In the second or de-escalation phase (Phase 2), which started on 28 April and had not concluded at the time of submission of this paper, a trend towards decreasing numbers of new infections was seen both on a national and on a local level, with the Spanish government relaxing lockdown measures. This enabled a gradual return to normal routines and the performance of larger numbers of elective procedures.

Epidemiological situation of Toledo in the different scenariosThe first patient diagnosed in Castilla-La Mancha was reported in Guadalajara on 1 March, and the first two cases in Toledo were recorded on 3 March. Between that day and 15 March, there were a total of 401 cases in that autonomous community; of these, 162 were hospitalised, 19 were in intensive care unit (ICU) beds, 10 died and just 12 were discharged. In Toledo, of the 98 diagnosed cases, five were discharged or recovered and two died.1 No data breakdown by province is available.

Phase 1As of the first week of this phase, cases piled up quickly; the most severely ill patients filled emergency departments, where the admission rate was 36% (the normal admission rate is less than 12%). Discharges of non-COVID patients were expedited and the hospital was transformed, becoming dedicated to the care of COVID-19 patients. ICU and critical-care beds doubled or even tripled. A decision was made to work as a part of a network of 17 regional health department hospitals. On 19 March, in Toledo, there were 195 admitted patients, 14 in the ICU, 20 having died and just 14 having been discharged. However, the real barometer of the situation was seen at the peak of the pandemic, on 1 April, when the hospital had 600 beds occupied by patients with COVID-19 (being at 80% capacity), ICU spots had tripled to 76 beds, more ICU beds at other hospitals in the city (Hospital Provincial [Provincial Hospital] and Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos [National Hospital for Paraplegics]) had to be opened up and post-anaesthesia recovery units and postoperative cardiac units had to be converted to critical-care units. The two above-mentioned hospitals opened up as many as 120 beds and professionals worked together; intensivists and anaesthetists worked on critical-care units, and internists, geriatric specialists, pulmonologists, cardiologists and physicians from other clinical specialisations worked on inpatient wards. The emergency department was also reorganised, and a great deal of pressure was heaped on emergency physicians, in particular when it came to triaging patients.

Phase 2On 28 April, 228 patients remained hospitalised at our hospital, concentrated on three wards. There were free ICU beds with non-COVID patient modules, and post-anaesthesia recovery units had been restored. On a provincial level, 1,522 patients had been discharged, but there were still 4,492 infected patients, with 291 new cases daily, and 580 patients had died.

Thus, in these two phases, the magnitude of the pandemic may be captured, as in a snapshot, with official and public data from our health department,1 at two points. The first is 1 April 2020, the day with the largest number of hospitalised COVID-19 patients in a context of maximum healthcare overload. The second is 28 April 2020, an inflection point from which the number of patients infected with and admitted for COVID-19 exhibited a sustained decreased thanks to the containment measures established in the previous weeks.

Impact of the pandemic on the activities of the interventional radiology roomAn observational, prospective study was conducted of consecutive cases of patients with confirmed COVID-19, cared for in our IR department during the pandemic, from 13 March to 11 May. To conduct the study, data thought to be important were collected, such as demographic data (gender and age), intervention date, reason for the intervention and its urgency and, as endpoints, the technical success and the clinical success of the procedure. Patients were followed up until the date of submission of the paper. Technical success was defined as a good final review of the interventional procedure, and clinical success was defined as improvement of patient symptoms. All patients signed the corresponding informed consent form, and the approval of the hospital's independent ethics committee (IEC) was obtained.

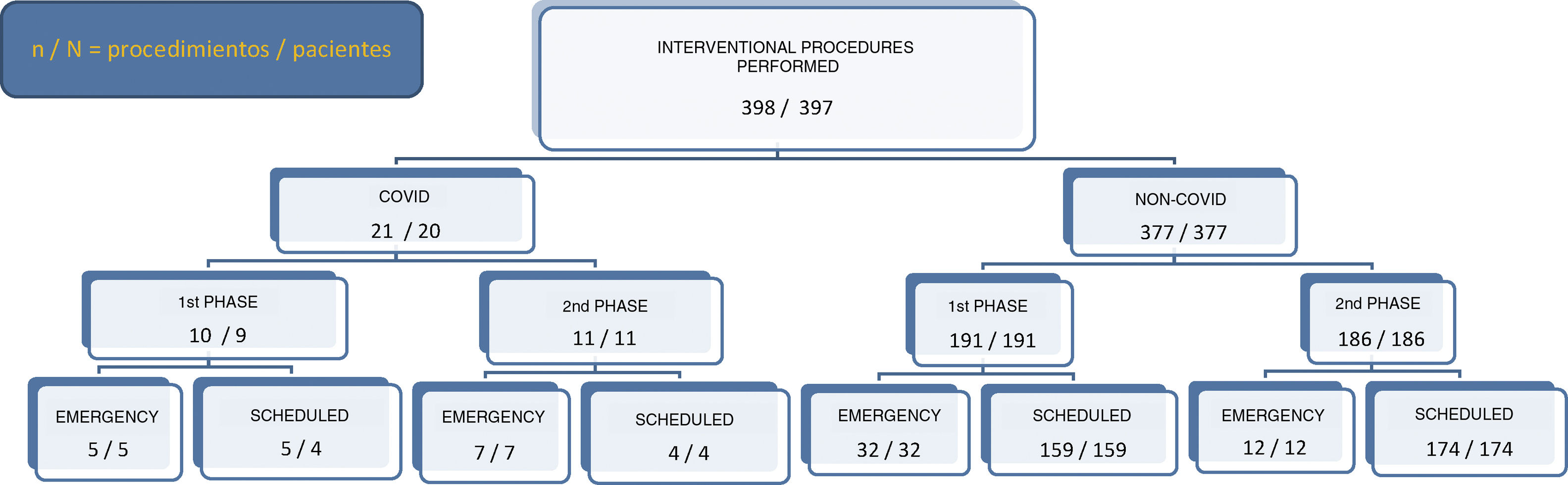

The procedures performed are presented in Fig. 4.

During the state of alarm and up to the time of publication of this article, a total of 398 interventional procedures were performed in 397 patients. Of these, 21 were performed in patients with COVID-19, 10 during the first phase and 11 during the second phase. 9 of these were scheduled procedures and 12 were emergency procedures.

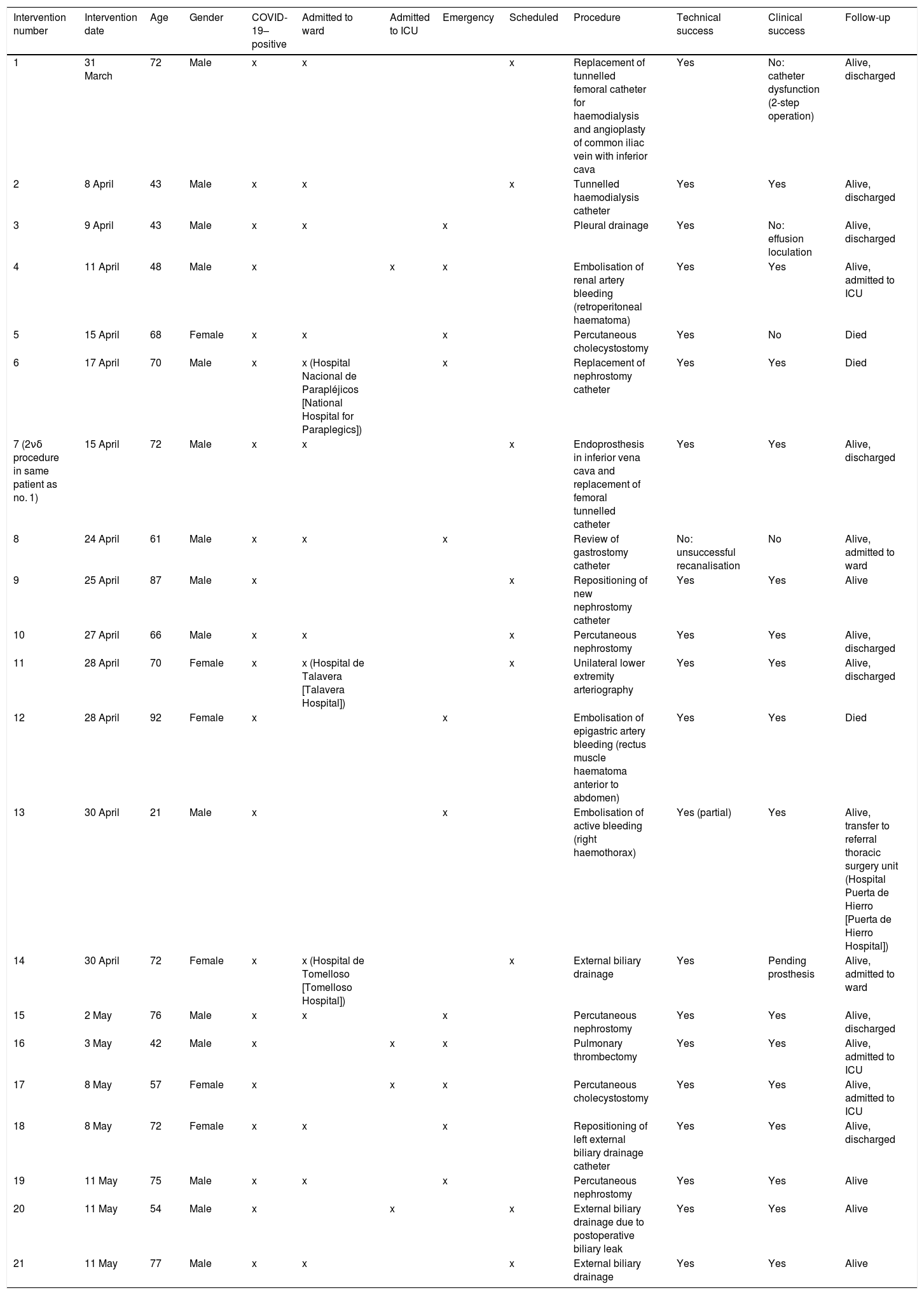

The type of procedure performed on each patient is shown in Table 1.

Procedures performed in COVID-19 patients in the interventional radiology unit.

| Intervention number | Intervention date | Age | Gender | COVID-19–positive | Admitted to ward | Admitted to ICU | Emergency | Scheduled | Procedure | Technical success | Clinical success | Follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31 March | 72 | Male | x | x | x | Replacement of tunnelled femoral catheter for haemodialysis and angioplasty of common iliac vein with inferior cava | Yes | No: catheter dysfunction (2-step operation) | Alive, discharged | ||

| 2 | 8 April | 43 | Male | x | x | x | Tunnelled haemodialysis catheter | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 3 | 9 April | 43 | Male | x | x | x | Pleural drainage | Yes | No: effusion loculation | Alive, discharged | ||

| 4 | 11 April | 48 | Male | x | x | x | Embolisation of renal artery bleeding (retroperitoneal haematoma) | Yes | Yes | Alive, admitted to ICU | ||

| 5 | 15 April | 68 | Female | x | x | x | Percutaneous cholecystostomy | Yes | No | Died | ||

| 6 | 17 April | 70 | Male | x | x (Hospital Nacional de Parapléjicos [National Hospital for Paraplegics]) | x | Replacement of nephrostomy catheter | Yes | Yes | Died | ||

| 7 (2νδ procedure in same patient as no. 1) | 15 April | 72 | Male | x | x | x | Endoprosthesis in inferior vena cava and replacement of femoral tunnelled catheter | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 8 | 24 April | 61 | Male | x | x | x | Review of gastrostomy catheter | No: unsuccessful recanalisation | No | Alive, admitted to ward | ||

| 9 | 25 April | 87 | Male | x | x | Repositioning of new nephrostomy catheter | Yes | Yes | Alive | |||

| 10 | 27 April | 66 | Male | x | x | x | Percutaneous nephrostomy | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 11 | 28 April | 70 | Female | x | x (Hospital de Talavera [Talavera Hospital]) | x | Unilateral lower extremity arteriography | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 12 | 28 April | 92 | Female | x | x | Embolisation of epigastric artery bleeding (rectus muscle haematoma anterior to abdomen) | Yes | Yes | Died | |||

| 13 | 30 April | 21 | Male | x | x | Embolisation of active bleeding (right haemothorax) | Yes (partial) | Yes | Alive, transfer to referral thoracic surgery unit (Hospital Puerta de Hierro [Puerta de Hierro Hospital]) | |||

| 14 | 30 April | 72 | Female | x | x (Hospital de Tomelloso [Tomelloso Hospital]) | x | External biliary drainage | Yes | Pending prosthesis | Alive, admitted to ward | ||

| 15 | 2 May | 76 | Male | x | x | x | Percutaneous nephrostomy | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 16 | 3 May | 42 | Male | x | x | x | Pulmonary thrombectomy | Yes | Yes | Alive, admitted to ICU | ||

| 17 | 8 May | 57 | Female | x | x | x | Percutaneous cholecystostomy | Yes | Yes | Alive, admitted to ICU | ||

| 18 | 8 May | 72 | Female | x | x | x | Repositioning of left external biliary drainage catheter | Yes | Yes | Alive, discharged | ||

| 19 | 11 May | 75 | Male | x | x | x | Percutaneous nephrostomy | Yes | Yes | Alive | ||

| 20 | 11 May | 54 | Male | x | x | x | External biliary drainage due to postoperative biliary leak | Yes | Yes | Alive | ||

| 21 | 11 May | 77 | Male | x | x | x | External biliary drainage | Yes | Yes | Alive |

Also shown are comparative overall outcomes of activities versus the same period in 2019 in these two phases, making a distinction between emergency and scheduled procedures (Fig. 5).

Discussion and conclusionThe pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 has significantly affected the autonomous community of Castilla-La Mancha, which, after Madrid and Catalonia, has had the highest incidence and prevalence of the disease in Spain. One of the hardest-hit provinces in this autonomous community has been Toledo, probably influenced first by its proximity to Madrid and the incessant flow of people between the two places in the weeks prior to the state of alarm, and second (but no less importantly) by the high percentage of its population who are older people residing in nursing homes (one of the highest in Spain).1 This has meant that a great many COVID-19 patients have been cared for at the city's hospital complex healthcare centres.

Elsewhere in the region, a major focus has been imported from Haro (La Rioja), in the area of Tomelloso (Ciudad Real), due to a super-spreader event where a family attended a funeral there at the time of peak disease transmission.1

Given the notoriety of the circumstances and their repercussions for the healthcare system on a global level, many articles have been published on the approach to patients with COVID-19 in IR areas. For example, an Italian team published an article reporting measures for prevention and coordination established in the interventional department of a hospital in Milan.2 A Chinese article reported a similar situation in describing the experience in a hospital with a high healthcare burden in Zhongda, in the region of Nanjing (China).5 That article briefly listed the emergency and preferential procedures performed at the peak of the pandemic, making a clear distinction between three phases, and conducted a comparative analysis of the results obtained against the figures for procedures performed the previous year. Another article from Singapore included summary data from eight procedures performed in patients with COVID-19 at the main hospital of Singapore up to the time of that article's publication.11

Without a doubt, COVID-19 took its toll on our hospital. Its peak prevalence threatened to overwhelm the hospital's healthcare resources, demanding much of many specialists on the front line, such as intensivists, anaesthetists and emergency physicians, but also on inpatient wards for joint teams of internists, geriatric specialists, pulmonologists and, to a lesser extent, other clinical specialists.

In the IR area, the repercussions were felt a few days later, when there was already a significant increase in COVID-19–positive ward- and ICU-admitted patients. This gave us a certain window to conscientiously prepare ourselves by designing circuits with the help of the Preventive Medicine Department and with some online refresher sessions on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and protective measures adapted to our setting by Occupational Hazards.

Hence, when this study concluded, there had been two months of intense activity with patients with confirmed COVID-19 involving all unit staff (interventional radiologists; all nursing staff, both regular and on-call; X-ray technicians; clinical auxiliary staff; and porters).

Along with that activity, care continued to be provided to other patients requiring haematological and oncological, emergency or preferential care on a morning schedule. As of the final week of phase 2, care resumed for patients admitted for other reasons or for diseases whose treatment could not be delayed.

The total recorded activity was seen to decrease by 21.49% compared to the same period in 2019 (398 current patients versus 507 patients cared for in 2019), but with different findings by phase, since in Phase 1, activity decreased by 38.71%, but in Phase 2, there was actually a 9.61% rebound in activity in favour of 2020. This reflects the scant delay permitted by interventional procedures; in Phase 2, a portion of the postponed procedures had to be performed, resulting in an increase in activity.

Analysis of the patient and activity data recorded in the above-mentioned articles reveals a surprising percentage of reduction in activity mentioned in the article from China,5 by 60%, if all phases are taken into account, compared to our 22%. This might have been related either to the extent of the measures demanded by the Chinese government to ensure control of infection transmission or to the high healthcare burden under normal conditions at the hospital in Zhongda. This burden is considerably higher than our own in terms of number of preferential procedures, which were the most heavily curtailed.

Also striking were the large numbers of patients with COVID-19 treated by us compared to Singapore. This difference may have been due to the duration of each study and the prevalence and incidence of the disease when each study was conducted, given the fact that our own study was conducted at the height of the pandemic. In addition, at present, there are no available publications centred on a registry of patients with COVID-19 cared for in IR units in European countries such as Italy, with which our results might be compared.

However, there is consistency in terms of reorganisation of angiography rooms (circuits), measures for deep cleaning and disinfection of spaces, and methodical preparation of healthcare staff with PPE.

In conclusion, to reflect on our learning from this situation, we would like to point out that the pandemic has had a profound impact on the foundations of our healthcare system in general and our IR unit in particular, both due to the need to adopt strict measures for preventing infection transmission — resulting in a lengthened procedure time — and due to the repercussions that it has had for all other scheduled activities, having reduced them by 22% at its peak. At this point, we find it important to mention the need to have a third angiography room in the future to ensure a clean circuit at all times; the importance of establishing and standardising comprehensive cleaning and individual protection measures; and the crucial necessity of working as a team, both within a single unit and across specialisations, under circumstances as extreme as those we have endured.

It is true that robust conclusions cannot be drawn from this study, given its limitations, the meagre number of patients seen up to now and the few endpoints studied. Hence, it would be beneficial and desirable to conduct multicentre studies in the future with larger caseloads and participation by more angiography rooms across Spain.

Finally, in line with remarks made by Luis H. Ros Mendoza, Editor-in-Chief of the journal Radiología, in his article "Coronavirus y radiología. Consideraciones sobre la crisis" [Coronavirus and radiology. Considerations on the crisis],12 this global crisis represents a challenge to make our healthcare system stronger and better. The aim of this article is to contribute to the scientific community's expanding knowledge and understanding through our experience and the recommendations of the SERAM8 and SERVEI7, who we publicly thank for their efforts and dedication.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: ICG, CLP.

- 2

Study concept: ICG, CLP.

- 3

Study design: ICG, CLP.

- 4

Data collection: ICG, CAM, IDP, IGR, CLP.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: ICG, CLP.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: ICG.

- 8

Drafting of the article: ICG, CLP.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: ICG, CAM, IDP, IGR, CLP.

- 10

Approval of the final version: ICG, CAM, IDP, IGR, CLP.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: García IC, Molina CA, Paillacho IDD, Rodríguez IGH, Lanciego C. La pandemia COVID-19 y su repercusión en la unidad de radiología intervencionista: nuestra experiencia. Radiología. 2021;63:170–179.