Cryptogenic liver abscesses (CLA) caused by hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (hvKP) strains are emerging in Western countries. The aim of the study was to describe the clinical characteristics of patients from Argentina with hvKP-related CLA as well as the molecular analysis of isolated strains. A retrospective chart review of 15 patients hospitalized in 8 hospitals of Argentina between October 2015 and November 2018 was performed. PCR assays for genes associated with capsular and multilocus sequence typing (MLST) determination and virulence factors were conducted in 8 hvKP isolates from these patients. We found that the mean age of patients was 60 years, 73% of them were men and 40% suffered from diabetes. Bacteremia was detected in 60% of them and 73% had ≥1 metastatic foci of infection. There were no in-hospital deaths, but two patients with endophthalmitis required eye enucleation. Of the 8 studied isolates, 4 belonged to K1 and 4 to K2 serotypes, with the rpmA and iroB genes being present in all of them, and isolates 7 and 5 also harboring the iucA and the rmpA2 genes, respectively. MSLT analysis showed that most of the K1 serotypes belonged to ST23 while a diverse MLST pattern was observed among the K2 strains. In addition, the four hvKP strains associated with metastatic complications and belonging to three distinct sequence types, exhibited the rpmA, iroB and iuc virulence genes. We were able to demonstrate important morbidity associated with this syndrome, a significant diversity in the hvKP clones causing CLA in Argentina, and the potential utility of the rpmA and iroB genes as predictors of virulence.

Los abscesos hepáticos criptogénicos causados por cepas de Klebsiella pneumoniae hipervirulentas (KPhv) están emergiendo en países occidentales. Los objetivos de este trabajo fueron describir las características clínicas de pacientes con abscesos hepáticos criptogénicos asociados a KPhv en Argentina y efectuar el análisis molecular de dichas cepas. Se realizó una revisión retrospectiva de las historias clínicas de 15 pacientes hospitalizados en 8 hospitales entre octubre de 2015 y noviembre de 2018. La metodología incluyó PCR para detectar genes asociados a la cápsula bacteriana y otros factores de virulencia, así como el análisis clonal mediante multilocus sequence typing de 8 aislamientos de KPhv. La edad promedio de los pacientes fue 60 años, el 73% fueron varones y el 40% tenía diabetes. El 60% presentó bacteriemia y el 73% al menos un foco metastásico. No se registraron muertes y 2 pacientes con endoftalmitis requirieron enucleación ocular. De los 8 aislamientos estudiados, 4 presentaron serotipo capsular K1 y los 4 restantes, serotipo capsular K2. Todos los aislamientos portaban los genes rpmA e iroB, mientras que 7 y 5 aislamientos también portaban los genes iucA y rmpA2, respectivamente. El análisis por multilocus sequence typing mostró que la mayoría de las cepas K1 correspondían al secuenciotipo 23, mientras que hubo diversidad entre las cepas K2. Asimismo, las 4 cepas de KPhv asociadas a complicaciones metastásicas, pertenecientes a 3 secuenciotipos distintos, presentaron los genes de virulencia rpmA, iroB e iucA. En suma, pudimos evidenciar una importante morbilidad asociada a este síndrome, una diversidad en los clones de KPhv causantes de abscesos hepáticos criptogénicos en Argentina y la potencial utilidad de los genes rpmA e iroB como predictores de virulencia.

Pyogenic liver abscesses (PLAs) are serious life-threatening infections with an incidence of 1.1 to 17.6 per 100000 persons throughout the world, with a mortality rate of 6–19%, even in treated patients19. PLAs are usually related to biliary obstruction, intra-abdominal infections (i, suppurative pylephlebitis, appendicitis, diverticulitis or peritonitis), and colonic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, diverticulitis, colon cancer and polyps. Less frequently, liver abscesses arise from a systemic infection through hematological seeding28. Cryptogenic liver abscesses (CLAs) are designated when no obvious extrahepatic source of infection is identified and they account for about 20% of the PLAs in industrialized countries28.

Since the mid-1980s, reports of CLAs caused by mucoid strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae have been described in countries from the Asian Pacific Rim17. In the following years, an increasing number of cases were reported worldwide22,27 representing a serious emerging infectious disease. These K. pneumoniae strains have been initially termed “hypermucoviscous” due the formation of viscous strings of >5mm in length when a loop is used to stretch the colony (positive “string test”). However, due to their invasiveness, genotypic features, and associated clinical presentation, they were later renamed as hypervirulent K. pneumoniae (hvKP)24,29. Even though the outcome of patients with CLA is more favorable than that of those suffering from non-cryptogenic pyogenic liver abscesses, the typical spread of the infection to other organs has been associated with significant morbidity7,27. Moreover, cases of CLAs caused by multidrug resistant hvKP, including carbapenem-resistant hvKP3, have raised remarkable concerns.

A number of accessory virulence genes have been linked to hvKP strains such as iucA (aerobactin siderophore biosynthesis) and iroB (salmochelin siderophore biosynthesis), as well as rmpA and rmpA2, both of which are involved in increased capsule expression and hypermucoviscosity25,33. Several capsule serotypes were described among hvKP strains, but K1 and K2 account for approximately 70% of them21,24. Furthermore, certain clones appear to predominate within each capsular serotypes; for instance, ST23 is the most frequent sequence type (ST) among K1 strains while ST65/ST375, ST374, ST66, and ST86 among K2 ones15,21,32. Since the documented spread of these hvKP strains represent a serious public health threat, it is critical to have a better understanding of the epidemiological behavior of these strains. As cases of CLAs caused by hvKP have been sporadically reported from Latin America4,31, we aimed to describe the clinical characteristics of 15 hospitalized patients with CLAs from different cities of Argentina and the molecular analysis of 8 hvKP strains isolated from these patients.

Material and methodsPatients with cryptogenic liver abscesses. A retrospective study was conducted obtaining clinical information through the chart reviews from 15 hospitalized patients diagnosed with CLAs in 8 hospitals from 4 different cities in Argentina (Buenos Aires, Rosario, Mendoza, and La Plata) between October 2015 and November 2018. Cases were identified by a surveillance evaluation implemented within a working group in the Argentinian Society of Infectious Diseases (SADI). Clinical data from patients with confirmed CLA caused by hvKP were collected in a preformed spreadsheet. Each case required the presence of the liver abscess and the isolation of this pathogen from samples obtained from blood or liver abscess fluid. The study was approved by a local ethics committee and due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need for a signed informed consent was waived.

Bacterial isolatesFrom this series of patients, 8 K. pneumoniae isolates recovered from liver abscesses and/or blood cultures exhibiting the hypermucoviscosity phenotype by a positive string test27 were available for further molecular analysis. The string test was considered positive when a viscous string of more than 5mm in length was obtained by stretching the bacterial colonies grown overnight on a blood agar plate with a bacteriological loop. Identification and antimicrobial susceptibility assays were performed using the BD Phoenix™ System (Becton Dickinson).

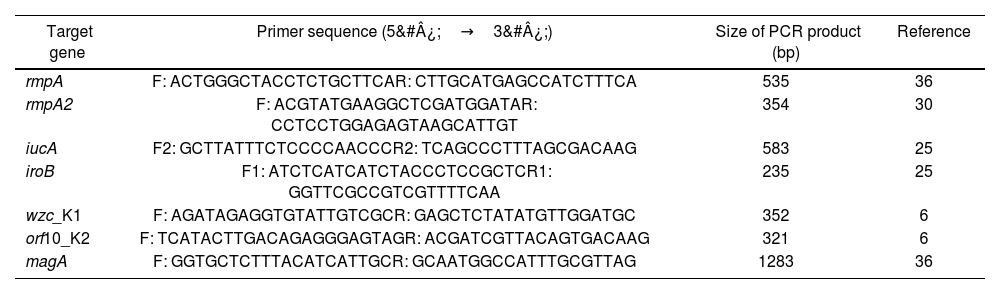

Identification of virulence-associated genesFour genes for virulence including iucA, iroB, plasmid-borne rmpA and an isoform rmpA2 were identified by PCR with the specific primers previously reported25,30,36 (Table 1).

Primers used for amplification of the target genes of K. pneumoniae isolates.

| Target gene | Primer sequence (5&#¿;→3&#¿;) | Size of PCR product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| rmpA | F: ACTGGGCTACCTCTGCTTCAR: CTTGCATGAGCCATCTTTCA | 535 | 36 |

| rmpA2 | F: ACGTATGAAGGCTCGATGGATAR: CCTCCTGGAGAGTAAGCATTGT | 354 | 30 |

| iucA | F2: GCTTATTTCTCCCCAACCCR2: TCAGCCCTTTAGCGACAAG | 583 | 25 |

| iroB | F1: ATCTCATCATCTACCCTCCGCTCR1: GGTTCGCCGTCGTTTTCAA | 235 | 25 |

| wzc_K1 | F: AGATAGAGGTGTATTGTCGCR: GAGCTCTATATGTTGGATGC | 352 | 6 |

| orf10_K2 | F: TCATACTTGACAGAGGGAGTAGR: ACGATCGTTACAGTGACAAG | 321 | 6 |

| magA | F: GGTGCTCTTTACATCATTGCR: GCAATGGCCATTTGCGTTAG | 1283 | 36 |

The detection of capsular K1 and K2 serotypes of these hvKP strains was performed by PCR assays previously reported6. The specific primers amplifying the wzc gene were used to identify K1 strains, and those corresponding to the open reading frame (ORF)-10 region from the cps gene cluster to detect K2 ones6. Additionally, a PCR was performed to amplify magA (mucoviscosity-associated gene A), a chromosome gene involved in the biosynthesis of the outer core lipopolysaccharide, encoded on the operon responsible for capsular serotype K1, which has been linked to the K. pneumoniae hypervirulent phenotype36.

Detection of clones employing molecular methodsThe clonal relatedness among the hvKP isolates was based on multilocus sequence typing (MLST) performed by amplification and sequencing of the standard seven housekeeping genes of K. pneumoniae according to the Pasteur Institute MLST website (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html).

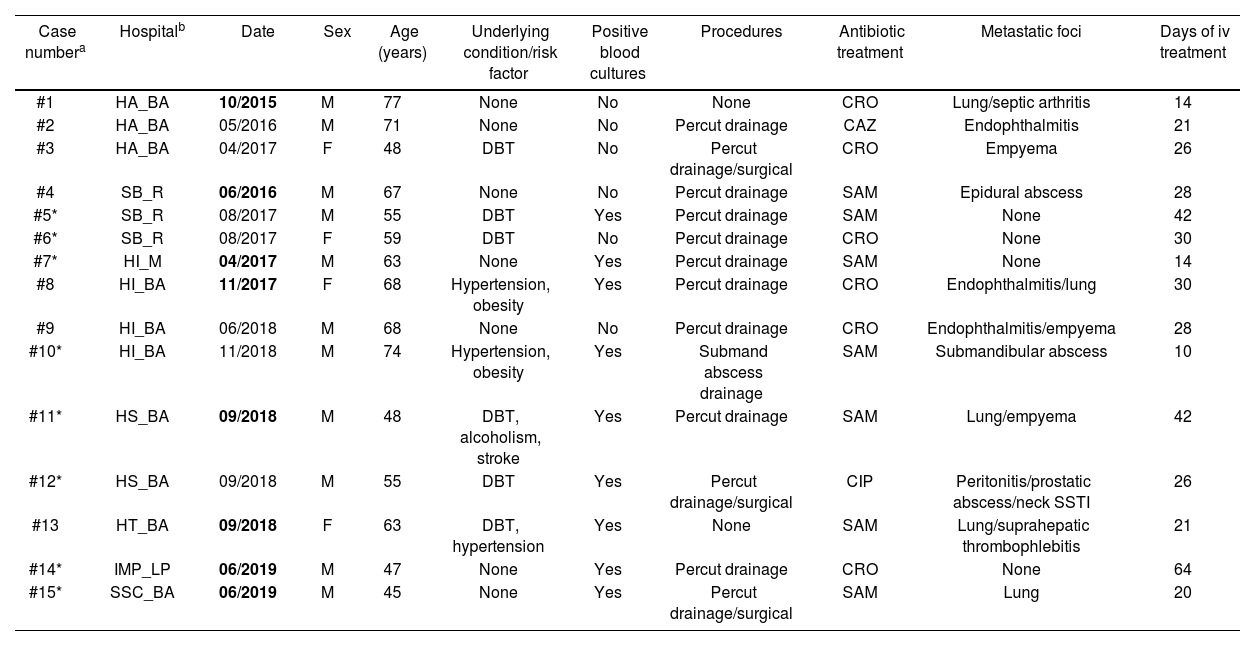

ResultsFifteen patients diagnosed with CLA caused by hvKP strains were included in the analysis (Table 2). They were non-Asian descent individuals, 11 (73%) of whom were men with a mean age of 60 years (range: 45–77 years). Diabetes was the most frequent comorbidity (n=6; 40%) and in 9 (60%) of the cases the corresponding hvKP strain was isolated from blood cultures. Percutaneous drainage of the liver abscess was performed in most study patients (n=12; 80%), although in two (13%) individuals, an open surgical procedure was required. Eleven patients (73%) had clinical and radiological confirmation of at least one metastatic focus of infection: 4 patients had one, 6 had two, and one had three. The anatomical sites of infection spread outside the liver are listed in Table 2.

Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 15 patients with cryptogenic liver abscessesa

| Case numbera | Hospitalb | Date | Sex | Age (years) | Underlying condition/risk factor | Positive blood cultures | Procedures | Antibiotic treatment | Metastatic foci | Days of iv treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1 | HA_BA | 10/2015 | M | 77 | None | No | None | CRO | Lung/septic arthritis | 14 |

| #2 | HA_BA | 05/2016 | M | 71 | None | No | Percut drainage | CAZ | Endophthalmitis | 21 |

| #3 | HA_BA | 04/2017 | F | 48 | DBT | No | Percut drainage/surgical | CRO | Empyema | 26 |

| #4 | SB_R | 06/2016 | M | 67 | None | No | Percut drainage | SAM | Epidural abscess | 28 |

| #5* | SB_R | 08/2017 | M | 55 | DBT | Yes | Percut drainage | SAM | None | 42 |

| #6* | SB_R | 08/2017 | F | 59 | DBT | No | Percut drainage | CRO | None | 30 |

| #7* | HI_M | 04/2017 | M | 63 | None | Yes | Percut drainage | SAM | None | 14 |

| #8 | HI_BA | 11/2017 | F | 68 | Hypertension, obesity | Yes | Percut drainage | CRO | Endophthalmitis/lung | 30 |

| #9 | HI_BA | 06/2018 | M | 68 | None | No | Percut drainage | CRO | Endophthalmitis/empyema | 28 |

| #10* | HI_BA | 11/2018 | M | 74 | Hypertension, obesity | Yes | Submand abscess drainage | SAM | Submandibular abscess | 10 |

| #11* | HS_BA | 09/2018 | M | 48 | DBT, alcoholism, stroke | Yes | Percut drainage | SAM | Lung/empyema | 42 |

| #12* | HS_BA | 09/2018 | M | 55 | DBT | Yes | Percut drainage/surgical | CIP | Peritonitis/prostatic abscess/neck SSTI | 26 |

| #13 | HT_BA | 09/2018 | F | 63 | DBT, hypertension | Yes | None | SAM | Lung/suprahepatic thrombophlebitis | 21 |

| #14* | IMP_LP | 06/2019 | M | 47 | None | Yes | Percut drainage | CRO | None | 64 |

| #15* | SSC_BA | 06/2019 | M | 45 | None | Yes | Percut drainage/surgical | SAM | Lung | 20 |

M: male; F: female; DBT: diabetes; IV treatment: intravenous treatment; SSTI: skin soft tissue infections; CRO: ceftriaxone; CAZ: ceftazidime; SAM: ampicillin/sulbactam; CIP: ciprofloxacin; ND: not determined; Percut: percutaneous.

The cases are ordered taking into account the chronology as revealed by the first strain found in each hospital (dates in bold for the first one) but grouped together with the subsequent cases for each hospital. The strains recovered from cases #5, #6, #7, #10, #11, #12, #14 and #15, indicated with asterisks (*), are included in this study for molecular characterization (see Table 3).

HA_BA: Hospital Argerich, Buenos Aires; SB_R: Sanatorio Británico, Rosario; HI_M: Hospital Italiano, Mendoza; HI_BA: Hospital Italiano, Buenos Aires; HS_CABA: Hospital Santojanni, Buenos Aires; HT_BA: Hospital Tornu, Buenos Aires; IMP_BA: Instituto Médico Platense, La Plata, Provincia de Buenos Aires; SSC_BA: Sanatorio Sagrado Corazón, Buenos Aires.

Reflecting the severity of the CLA, intravenous antibiotic treatment was administered for a mean of 32 days (range: 14–64 days). All the patients were considered cured at the end of hospitalization although two patients with endophthalmitis required eye enucleation. The 15 isolates were reported as susceptible to all the tested antibiotics except ampicillin, to which K. pneumoniae is intrinsically resistant.

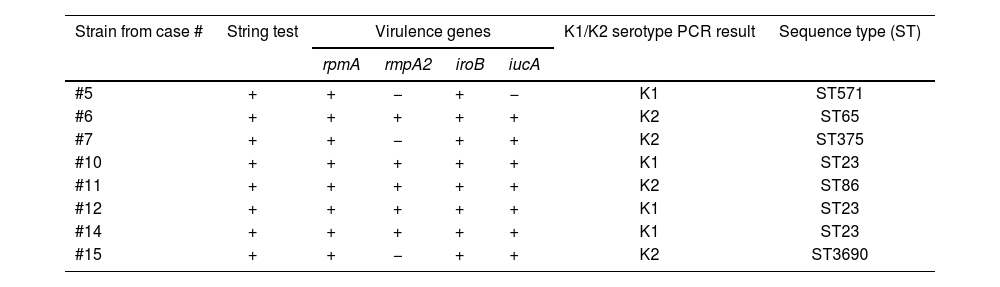

The eight available K. pneumoniae isolates for analysis displayed a positive string test and carried the plasmid-mediated rpmA virulence gene (Table 3) compatible with the hypermucoviscous phenotype, also uncovering its association to the K. pneumoniae hypervirulent pathotype14. In addition, other genes associated with hvKP strains, such as the iroB in all the 8 isolates, and the iucA and the rmpA2 in the 7 and 5 isolates, were identified. K1 isolates were positive for the wzc_K1 and the magA gene (renamed as wzy_K1)35 and the ORF-10 region from the cps gene cluster were found in K2 ones (Table 3).

Characteristics of the 8 hypervirulent K. pneumoniae clinical strains studieda

| Strain from case # | String test | Virulence genes | K1/K2 serotype PCR result | Sequence type (ST) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rpmA | rmpA2 | iroB | iucA | ||||

| #5 | + | + | − | + | − | K1 | ST571 |

| #6 | + | + | + | + | + | K2 | ST65 |

| #7 | + | + | − | + | + | K2 | ST375 |

| #10 | + | + | + | + | + | K1 | ST23 |

| #11 | + | + | + | + | + | K2 | ST86 |

| #12 | + | + | + | + | + | K1 | ST23 |

| #14 | + | + | + | + | + | K1 | ST23 |

| #15 | + | + | − | + | + | K2 | ST3690 |

The MLST analysis showed that, among the 4 K1 strains, 3 belonged to ST23 and one to ST571, while the K2 ones were represented by diverse STs, including ST65 and ST375 (from the same clonal complex)37, ST86, and the most recently described ST369021 (Table 3).

Overall, these results revealed that the K1/ST23 strains exhibited all the virulence genes included in this study (Table 3). Interestingly, all the K2 strains characterized here were positive for the rpmA, iroB and iucA genes (Table 3). In turn, the association between the presence of metastatic foci and the involved strains showed that metastatic complications were observed in 4 of the 8 cases characterized in this study. Specifically, the four hvKP strains associated with metastatic complications, belonging to three distinct sequence types including K1/ST23 (#10 and #12), K2/ST86 (#11), and K2/ST3690 (#15) hvKP strains (Table 2), demonstrated clonal diversity.

DiscussionThis is the largest series of patients with CLA reported from Latin America, including the molecular analysis of 8 hvKP strains. In agreement with previous studies1,22,29, we found that all the cases were community-acquired infections, men were the predominant sex, diabetes was the most common comorbidity, more than 50% of the patients had positive blood cultures, the isolated K. pneumoniae strains were susceptible to the majority of the antibiotics tested, and a satisfactory outcome was observed in the majority of the patients by the end of their hospital stay. However, we observed that 73% of the patients developed at least one focus of metastatic infection spread. This rate is considerably higher than that reported by others, ranging between 3.5% and 20% in one study13 and 10–45% in another18.

The most common diagnoses resulting from the infection spread were lung abscesses, empyema, endophthalmitis, and involvement of various other anatomical sites such as prostatic and epidural abscesses. Almost half of the patients from our cohort suffered from more than one infected site outside the liver. We cannot find a plausible justification for the observed high rate of metastatic complications. An unmeasured delay in hospitalization and/or in the drainage of liver abscesses could be a hypothesis, particularly in the 60% of the patients who had bacteremia. It should be noted that three patients (20%) developed endogenous endophthalmitis, the most threatened complication of this syndrome, a considerably higher incidence than the 4.5% reported in a systematic review11 of 11889 patients. These two patients underwent eye enucleation, highlighting the importance of the ophthalmologic screening in patients with CLA for an early diagnosis, treatment, and visual preservation26.

The pheno-genotypic characterization of the 8 hvKP strains analyzed from this cohort of patients showed equal distribution of K1 and K2 serotypes. Most of the K1 strains belonged to the ST23 clone, which is considered the archetypal clone among K1 hvKP strains34. Additionally, the finding of this clone in patients from different hospitals (Table 3) highlights their widespread distribution in the community. This type of clonality pattern among K1/K2 capsular serotypes has already been described22.

Siderophores and mucoid regulators appear to play key roles in conferring the hypervirulent phenotype to these K. pneumoniae strains, and the plasmid-associated genes iuc, iro, and rmpA/rmpA2 have been recognized as important predictors for this phenotypic trait12,33.

In this context, we detected these four virulence genes in five of the eight strains analyzed (three K1/ST23 and two K2 strains (ST65 and ST86) (Table 3). It is worth noting that the four strains recovered from patients with metastatic foci (i.e. ST23, ST86 and ST3690 clones) revealed the four mentioned virulence genes, except for the rmpA2 gene in the last clone. In addition, the two virulence genes positive for the 8 studied strains were rpmA and iroB, thus confirming their capacity as pathogenic markers of hvKP.

With regard to pathogenesis, the exact mechanism by which hvKP strains cause CLA is unclear. It was hypothesized that hvKP strains must first colonize the gastrointestinal tract, then cross the intestinal barrier, to later invade the liver; at this stage, the role of liver Kupffer cells and macrophages appear to be critical in the control of the infection process9. In vitro studies have shown that K1 and K2 capsular serotypes were more resistant than non-K1/K2 ones to phagocytosis and intracellular killing by neutrophils16.

The definition of hvKP has not been clearly outlined and indeed, none of the phenotypic or genotypic tests alone is specific for hypervirulence. However, the presence of hypercapsule, macromolecular exopolysaccharide or excessive siderophores in hvKP and not in classical K. pneumoniae (cKP) strains suggest that these are significant virulence contributors to the observed hypervirulence5. Nonetheless, the role of each virulence factor and the degree of involvement in these strains have been difficult to ascertain. Animal models have confirmed the increased lethality of hvKP strains compared to cKP and partially virulent hvKP strains, although this was observed in some but not all of the mouse models tested23.

Except for intrinsic resistance to ampicillin, hvKP strains are commonly susceptible to a variety of antibiotics; however, the occurrence of liver abscesses caused by hvKP strains carrying multidrug resistant genes have been initially reported with strains carrying extended-spectrum beta-lactamases genes15 in China and in Brazil20. More worrisome, a recent report from Wuhan, China, found that 24 of 45 (53%) clinical hvKP isolates were carbapenemase producers and that 8 of them, although clonally related, were co-producers of NDM-1 and KPC-210. High-risk ST23 hvKp strains producing KPC-2 and dual-carbapenemase-producing KPC-2/VIM-1 were reported in Argentina2 and Chile8, respectively. This occurrence certainly carries potentially serious public health consequences.

The main limitations of this study include the retrospective nature of the reports from each participating hospital, which could have led to a selection bias towards patients with more extensive disease and the limited number of hvKP strains available for molecular analysis.

ConclusionsThe CLA syndrome caused by community-acquired strains of hvKP is an emerging worldwide public health concern. We report a series of cases from Argentina highlighting a significant prevalence of metastatic foci of infection. Attending physicians should be aware of this syndrome to provide the appropriate treatment and prevent significant central nervous system or sight-threatening ophthalmologic complications due to hvKP. The hypermucoviscous phenotype of the hvKP strains can be identified using the positive string test and PCR for virulence genes such as rmpA and/or iroB. Epidemiological and molecular studies analyzing the relationship between hvKP cloning spreads and susceptible hosts continue to be crucial, as well as the progressive acquisition of virulence genes among multi-drug resistant clones of K. pneumoniae.

CRediT authorship contribution statementThe authors declare that they have all contributed to the conceptualization and methodology of the study. ECN: original draft writing, data collection, supervision, and revision and editing of the writing. ML, PS, CN, MZ, VR, RZ: data collection; AV and AM: data collection, writing review and editing; AL, PM, MR and VD: laboratory studies, writing revision and editing.

Ethical approvalThe study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Sanatorio Británico, Rosario, Argentina and by each local Ethics Committee.

Consent to participateSince this was a retrospective study, the bacterial analysis was conducted years after the patients’ episodes of infection, and confidentiality and anonymity were reassured throughout the data collection process. The need for a signed informed consent was waived.

Consent to publishAs there are no individual details, imaging or videos, the consent for publication was waived.

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

We wish to thank the clinical and microbiology staff of each participating hospital.