Headache is a very common neurological symptom. It is the first reason for consultation in neurology. About hospitalized patients, we do not have epidemiological data on the global prevalence of headaches in hospitalized patients.

ObjectiveTo describe the prevalence of headaches in hospitalized patients, their triggers, and the level of compliance with nursing records.

MethodologyThis is a descriptive, observational, and cross-sectional study at the Vall d'Hebron University Hospital (HUVH). The data collected were sociodemographic, related to the reason for admission and pain during admission. Statistical analysis was performed with R v4.1.1.

ResultsOf the 45 admitted patients, 55% (25/45) participated, 55% (25/45) participated, 64% (16/25) were women. 60% (15/25) had presented headaches during admission, of which 73.3% (11/15) occurred in the last 24 hours. The 33.3% (5/15) recognized stress as the most frequent trigger, noise (5/15), and income derivatives (3/15). During the daily follow-up by the nurse, 100% (25/25) of the patients answered that they had been asked about pain in general and 32% (8/25) specifically about headaches. No records were obtained due to the computer program's non-existence of nursing clinical variables.

ConclussionHeadache is a symptom that occurs prevalently in hospitalized patients. Stress and noise seem to be triggers of this situation. Certain behaviors on the part of health centers and professionals could help improve the care of these patients.

La cefalea es un síntoma neurológico muy común. En referencia a los pacientes hospitalizados, no disponemos de datos epidemiológicos de prevalencia global de cefalea en el paciente hospitalizado.

ObjetivoDescribir la prevalencia de la cefalea en pacientes hospitalizados, sus desencadenantes y nivel de cumplimiento de los registros de enfermería.

MetodologíaSe trata de un estudio descriptivo, observacional y transversal realizado en el área de neurociencias del Hospital Universitario Vall d’Hebron. Los datos recogidos fueron sociodemográficos, relacionados con el motivo de ingreso y el dolor durante el ingreso. El análisis estadístico se realizó con R v4.1.1.

ResultadosDe los 45 pacientes ingresados, participó el 55% (25/45), el 64% (16/25) eran mujeres. El 60% (15/25) había presentado cefalea durante el ingreso, de los cuales el 73,3% (11/15) fue en las últimas 24 h. Reconocían como posibles desencadenantes más frecuentes el estrés 33,3% (5/15), el ruido (5/15) y derivados por el ingreso (3/15). En cuanto al seguimiento diario por la enfermera, el 100% (25/25) de los pacientes respondieron que se les había preguntado por el dolor en general, y en un 32% (8/25) específicamente por la cefalea. No se había realizado ningún registro de cefalea en el programa informático de registro.

ConclusiónLa cefalea es síntoma que se presenta de manera frecuente en los pacientes hospitalizados. El estrés y el ruido parecen ser desencadenantes de esta situación. Es importante la implementación de registros y estrategias específicas para minimizar el impacto de la cefalea durante el ingreso.

Headache is a very common nuerological symptom.1 In populational studies conducted in Western countries, prevalence rates of 73–89% are reported in males and 92–99% in females.2

How the headache debuts, its clinical characteristics, and the symptoms that accompany it will inform as to its possible causes: environmental factors (such as headache attributed to the use of substances, such as alcohol), genetic factors, or diseases that provoke recurring headache (such as migraine or cluster headache) or serious illnesses that can be life-threatening (such as a brain bleed or meningitis).3

According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders,3 primary headaches are neurological diseases in which headache is the main symptom and is generally accompanied by a set of concommittant symptoms that characterise each one. The leading primary headaches are migraine, trigeminal autonomic headaches, or tension-type headaches.3,4

In the case of secondary headaches, the pain is a symptom of another either neurological or systemic disorder, and, in some cases, it can be serious. The leading secondary causes are infections, tumors, ischaemic or hemorrhagic stroke, stroke, injury, or trauma.3,5

Given the high prevalence, tremendous clinical heterogeneity, and variety of causes, headache is the number one presenting complaint in neurology, both in the Emergency Department and at outpatient clinics.6

With respect to hospitalised patients, the data are limited. We do not have epidemiological data regarding the prevalence of headache in the hospitalised patient populations from around the world and the scant studies to be found in the literature focus on special populations, such as during the postpartum period, with migraine and secondary headaches the most frequent causes in this group of subjects.7,8

In addition to the disease and medical causes that lead to hospitalisation, other factors, such as light, temperature, noise, or sharing a room can lead to an increase and/ or trigger the headache. It is important to bear in mind the situation itself of the patient, as well as having an illness that can be a source of psychological distress, sadness or anxiety, and other painful symptoms that would, in turn, contribute to worsening the headache.9

Nursing professionals are in charge of evaluating the presence of signs, symptoms, and possible complications, including headaches, of people while they are in the hospital.10 The hospital has standardised protocols and procedures to evaluate pain. Depending on the person’s situation, they will describe the recommended intervals between pain assessments. It is recommended that both the presence and absence of pain be recorded in the corresponding instrument. The assessment of headache is not specified in these protocols.

The primary objective of this study was to report the prevalence of headache among hospitalised patients, its possible triggers, and the degree to which the variable “headache” is recorded in nursing notes.

MethodsThis is a descriptive, observational, cross-sectional cohort study conducted at the Vall d'Hebron University Hospital (HUVH), a tertiary public university hospital located in Barcelona (Spain).

All the individuals who were admitted to the inpatient unit of the Neurology and Neurosurgery Service were included; this service comprises a total of 54 beds, 27 per service.

Those individuals who were unable to participate due to medical reasons (severity or isolation), communication limitations (language barrier, altered level of consciousness, impaired ability to understand or express themselves), and who did not agree to participate or sign the informed consent form were excluded.

The data were collected by the expert nurse of the Headache Unit of the HUVH in May, 2021.

The data of the participants who agreed to participate were obtained from three sources: the hospital’s computer programme (Systems, Applications, Products in Data Processing [SAP]), an ad hoc questionnaire, and from the computer programme of clinical nursing variables (Gacela [Programme for the harmonisation of the standard of care of the Generalitat de Catalunya (Catalan Government)]).11

From the SAP programme, information was gathered regarding the admitting unit, the service in charge, diagnosis (subdivided into neurovascular and non-neurovascular), room, socio-demographic variables (age and sex), date of admission, and days of stay.

Systematic questioning was performed using a semi-structured ad hoc questionnaire divided into two sections: one section pertaining to pre-admission and the second section referring to admission. Prior to admission: the presence of recurring headache; existence of a diagnosis of primary headache, if ‘yes’, what was the primary headache diagnosed (migraine, tension headache, trigeminal autonomic headache, other); medication usually taken to treat the pain and medication taken to prevent the headache. During hospitalisation: the possibility of continuing with their regular headache treatment, daily questioning about pain and headache, the presence of headache during hospitalisation, the presence of headache in the last 24 h, the intensity of the headache, triggers that may have caused the headache, medication to treat the pain, and whether the medication resolved the headache in less than two hours.

The results recorded for the variable «Headache Intensity» using the visual analogue scale (VAS) were obtained from the Gazelle clinical variables software.

The data were recorded in the RedCAP® digital data base.12

Data analysisThe descriptive analysis of clinical variables was carried out using frequency tables for categorical or nominal variables; the median as a measure of central tendency, and the interquartile range (Q1-Q3 interval) as a measure of dispersion for continuous variables.

To evaluate the differences between the group of patients who experienced headache and those who did not during their hospitalisation, Student’s t-test was used for variables with normal distribution and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for those that did not fulfil this criterion. Data normality was established by means of statistical tests (the Shapiro-Wilk test) and visual inspection (Q-Q plots). For categorical variables, the χ2 goodness-of-fit test was applied.

Statistical analyses were performed using the R v4.1.1 software package and all tests were conducted for a 5% level of significance.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Vall d’Hebron Hospital PR(AG)424/2020. All participantes were suitably informed about the purpose of the research for which written informed consent was requested. The research group is responsible for collecting and storing the data safely and confidentially, thereby safeguarding patients’ identity by anonymising clinical data in accordance with Law 3/2018 regarding data protection and guarantee of digital rights.

ResultsAt the time data were collected, there were 45 inpatients. Of the subjects who were studied, 55% (25/45) agreed to participate; 45% (20/45) were excluded on the following grounds: 22% (10/45) were unable to communicate, 17.7% (8/45) were not present in their room, and due to communication barriers in 4.4% (2/45) of the cases.

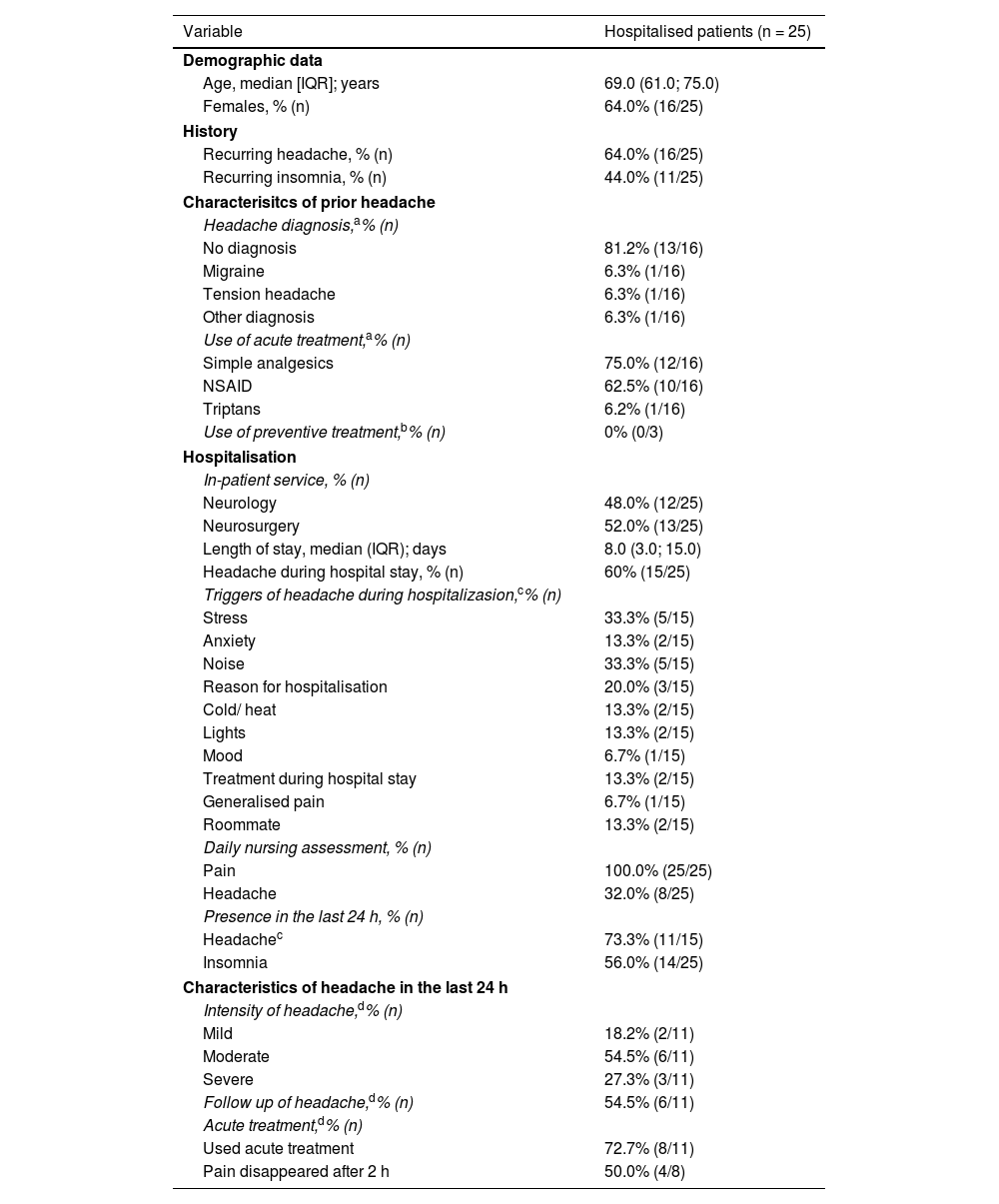

Table 1 displays the main demographic variables and results of the questionnaire. The mean age of the hospitalised patients was 69 years; the age range (minimum-maximum) of the individuals who agreed to participante in the study varied between 28 and 89 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 61.0; 75.0), y 64% (16/25) were female. Forty-eight percent (48%) of the patients (12/25) were hospitalised in the Neurology Service and 52.0% (13/25) in Neurosurgery. The participants who were interviewed were hospitalised for a mean of 8.0 (IQR: 3.0; 15.0) days.

Demographic data, clinical characteristics, and hospitalisation variable of the patients recruited.

| Variable | Hospitalised patients (n = 25) |

|---|---|

| Demographic data | |

| Age, median [IQR]; years | 69.0 (61.0; 75.0) |

| Females, % (n) | 64.0% (16/25) |

| History | |

| Recurring headache, % (n) | 64.0% (16/25) |

| Recurring insomnia, % (n) | 44.0% (11/25) |

| Characterisitcs of prior headache | |

| Headache diagnosis,a% (n) | |

| No diagnosis | 81.2% (13/16) |

| Migraine | 6.3% (1/16) |

| Tension headache | 6.3% (1/16) |

| Other diagnosis | 6.3% (1/16) |

| Use of acute treatment,a% (n) | |

| Simple analgesics | 75.0% (12/16) |

| NSAID | 62.5% (10/16) |

| Triptans | 6.2% (1/16) |

| Use of preventive treatment,b% (n) | 0% (0/3) |

| Hospitalisation | |

| In-patient service, % (n) | |

| Neurology | 48.0% (12/25) |

| Neurosurgery | 52.0% (13/25) |

| Length of stay, median (IQR); days | 8.0 (3.0; 15.0) |

| Headache during hospital stay, % (n) | 60% (15/25) |

| Triggers of headache during hospitalizasion,c% (n) | |

| Stress | 33.3% (5/15) |

| Anxiety | 13.3% (2/15) |

| Noise | 33.3% (5/15) |

| Reason for hospitalisation | 20.0% (3/15) |

| Cold/ heat | 13.3% (2/15) |

| Lights | 13.3% (2/15) |

| Mood | 6.7% (1/15) |

| Treatment during hospital stay | 13.3% (2/15) |

| Generalised pain | 6.7% (1/15) |

| Roommate | 13.3% (2/15) |

| Daily nursing assessment, % (n) | |

| Pain | 100.0% (25/25) |

| Headache | 32.0% (8/25) |

| Presence in the last 24 h, % (n) | |

| Headachec | 73.3% (11/15) |

| Insomnia | 56.0% (14/25) |

| Characteristics of headache in the last 24 h | |

| Intensity of headache,d% (n) | |

| Mild | 18.2% (2/11) |

| Moderate | 54.5% (6/11) |

| Severe | 27.3% (3/11) |

| Follow up of headache,d% (n) | 54.5% (6/11) |

| Acute treatment,d% (n) | |

| Used acute treatment | 72.7% (8/11) |

| Pain disappeared after 2 h | 50.0% (4/8) |

NSAID: non-steroidal anti-inflammatories; IQR: interquartile range (Q1–Q3).

Of the total number of participants who were interviewed, 60% (15/25) had suffered headache during their hospitalisation, 73.3% (11/15) of which in the last 24 h. The intensity of the pain experienced by these subjects who had experienced headache in the last 24 h was mild in 18.2% (2/11), moderate in 54.5% (6/11), and severe in 27.3% (3/11) of the cases. Pain treatment was received by 72.7% (8/11), of whom 50% (4/8) experienced pain relief in less than two hours.

Of the people admitted with a headache during admission, the possible triggers most commonly reported were stress (33.3% (5/15), noise (5/15), and the reason(s) for which they had been hospitalised (3/15).

Inasmuch as daily follow-up by the attending nurse is concerned, 100% (25/25) of the participants responded that they had been asked about pain in general, and 32% (8/25) reported that they had been asked specifically about headache.

No data were obtained for the variable «Intensity of the Headache», measured by the VAS scale, in the Gacela nursing clinical variables software because it had not been recorded.

We found that the only variable that statistically significantly correlated with the presence of headache during admission was the presence of recurring headache prior to admission: 93.3% (14/15) with prior headache vs. 20% (2/10) without prior headache (p < .001) with an associated relative risk (RR) of 1.46 (95% CI: 1.01–2.11). There were no statistically significant differences between the variables of age, sex, presence of reccurring insomnia, admitting department, length of hospital stay in days, or the reason for admission (Table 2).

Demographic, clinical, and hospitalisation differences between patients with and without headache during their hospitalisation.

| Variable | Without headache (n = 10) | With headache (n = 15) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic data | |||

| Age, median (IQR); years | 66.5 (61.2, 71.0) | 69.0 (60.5; 82.5) | .488a |

| Females, % (n) | 70.0% (7/10) | 60.0% (9/15) | .691c |

| History | |||

| Recurring headache, % (n) | 20.0% (2/10) | 93.3% (14/15) | <.001c |

| Recurring insomnia, % (n) | 30.0% (3/10) | 53.3% (8/15) | .414c |

| Hospitalisation | |||

| In-patient service, % (n) | |||

| Medicine | 50.0% (5/10) | 46.7% (7/15) | >.999c |

| Surgery | 50.0% (5/10) | 53.3% (8/15) | >.999c |

| Duration, median (IQR); years | 8.0 (2.0; 14.5) | 8.0 (5.0; 17.5) | .781b |

| Ay reason for admission, % (n) | |||

| Neurovascular | 50.0% (4/10) | 33.3% (4/15) | .648c |

| Non-neurovascular | 12.5% (1/10) | 41.7% (5/15) | .325c |

P value in bold indicates p < .050.

IQR: interquartile range (Q1–Q3).

The variables analysed among those individuals who had experienced headache during their hospitalisation and those who had suffered headache in the last 24 h (Table 3), the only variable that was statistically significantly associated with the presence of headache in the last 24 h was mean age (the mean age of patients without headache in the last 24 h was 83.5 years; the mean age of those with headache in the last 24 h was 67.0 years; p = .047). There were no statistically significant differences between sex, reoccurring headache, insomnia, admitting department, length of stay, reason for admission, or headache triggers.

Demographic, clinical, and hospitalisation differences between patients with and without headache during the last 24 h prior to inclusion.

| Variable | Without headache 24 h (n = 4) | With headache 24 h (n = 11) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR); years | 83.5 (75.8, 89.0) | 67.0 (58.5; 76.0) | .047a |

| Females, % (n) | 50.0% (2/4) | 63.6% (7/11) | >.999c |

| Recurring headache, % (n) | 100.0% (4/4) | 90.9% (10/11) | >.999c |

| Recurring insomnia, % (n) | 50.0% (2/4) | 54.5% (6/11) | >.999c |

| Hospitalisation | |||

| In-patient service, % (n) | |||

| Neurology | 75.0% (3/4) | 36.4% (4/11) | .282c |

| Neurosurgery | 25.0% (1/4) | 63.6% (7/11) | .282c |

| Duration, median (IQR); days | 7.5 (5.5; 8.0) | 13.0 (5.5; 22.5) | .148b |

| Aetiology reason for admission, % (n) | |||

| Neurovascular | 25.0% (1/4) | 27.3% (3/11) | >.999c |

| Non-neurovascular | 50.0% (2/4) | 27.3% (3/11) | .523c |

| Headache triggers, % (n) | |||

| Stress | 25.0% (1/4) | 36.4% (4/11) | >.999c |

| Anxiety | 0.0% (0/4) | 18.2% (2/11) | >.999c |

| Noise | 50.0% (2/4) | 27.3% (3/11) | .560a |

| Reason for hospitalisation | 0.0% (0/4) | 27.3% (3/11) | .516c |

| Cold/ heat | 25.0% (1/4) | 9.1% (1/11) | .476c |

| Lights | 75.0% (3/4) | 90.9% (10/11) | .476a |

| Mood | 75.0% (3/4) | 100.0% (11/11) | >.999a |

P value in bold indicates p < 050.

IQR: interquartile range (Q1–Q3).

We present the findings of a study carried out in the Neurosciences in-patient department in a a tertiary hospital with the main aim of determining the prevalence rate of headache among hospitalised patients.

The study reveals that headache is a common symptom among individuals who were capable of participating in a study that called for patient collaboration, with up to 60% admitted to neurology and neurosurgery departments having exhibited headache during the course of their stay. Therefore, despite the fact that headache is a frequent symptom among the population in general,2 it is particularly prevalent in neurology units.

Clinical guidelines and protocols recommend pain assessment with a validated scale10 such as a VAS. We have found that patients are properly asked about general pain and their answers are recorded, but that they are neither asked about headache nor are their responses recorded in their clinical history.

We observed that patients with a history of recurring headache were 50% more likely to present with headache during their hospital stay than those with no history of recurring headache. Consequently, the assessment performed by the nursing staff at the time of admission should inquire specifically about a history of previous recurring headache and their usual treatment, be it acute, preventive, or both. In addition, patients should be asked about the presence of headache on a daily basis. This can anticipate and enhance care for this symptom throughout the person’s hospitalisation.11

According to the literature, very few patients who reported recurring headache had a previously established diagnosis. Headache as a disabling and recurrent symptom is severely underdiagnosed and undertreated, possibly because of stigma, low interest, little interest, and low prioritisation by healthcare systems.13,14

As for the most common triggers, there is one group that we regard as non-modifiable, others that might be modifiable, and a third group that falls somewhere in between. The non-modifiable group are the reason for admission and stress. The modifiable factors are certain environmental aspects such as noise, light, and climate.15–17 Increased awareness on the part of the nursing staff can contribute to avoiding stimuli in the environment of the patient with headache; furthermore, the hospital centre could make light or temperature regulators available to the patient in their rooms so that they can adjust it to their optimum state of comfort, on the understanding that at certain times this can be modified for healthcare needs. There are two factors that can be viewed as intermediate: the patient's state of mind during hospitalisation or surgery and anxiety (certain non-pathological degrees), which could be included in the group of non-modifiable factors, but with proper health education and learning prior to admission and/or during their stay, they can modify how they cope with the illness by knowing about healthcare processes and uncerstanding the course of the illness and the disease process.18

In order to provide excellent, person-centred care, healthcare staff must be trained and. as a result, made aware that headache is a highly prevalent symptom among hospitalised patients. We believe that certain training programmes could raise awareness of the importance of headache as a highly prevalent symptom in hospitalised patients, and that assessment can lead to improved quality of life for the hospitalised patient. It could be helpful to have a nursing procedure in place in the hospital that recommends that headache be assessed and recorded in a standardised manner.18–20

Among the strengths of this study, it is worth mentioning that this is the first to address the question of prevalence of headache in the hospital carried out in the neurosciences area by a nurse expert in headache.

The main limitation is that it is a study performed in the area of neursciences, with a limited sample size and selection. Moreover, there is a selection bias, inasmuch as the primary pathology comprised neurological disorders and interventions in a significant number of patients with the possibility of a greater prevalence of secondary causes than in other hospital areas.

We believe that it is important to conduct the full study, in more units in the hospital, so as to be able to present a larger sample and consolidate the outcomes of this study.

ConclusionsHeadache is a common symptom and is highly prevalent in the hospital setting. More than half of the patients admitted into the Neurology and Neurosurgery services had experienced during the course of their stay.

Greater awareness of the hospital itself and healthcare personnel could contribute to making mechanisms available to the patient to be able to adapt modifiable stimuli to their needs, understanding that at certain times, they will have to adapt to clinical needs.

Hursing staff specifically assess headache on some occasion, but they do not record it in the computer programme of clinical variables. We feel that hospitals should be more committed to evaluating and recording this symptom in order to perform a more comprehensive follow up of inpatients.

The authors would like to thank the Department Care Support, Knowledge Management, and Evaluation of the HUVH. Second international prize for the best research project in neurological nursing.