Epidural analgesia is assumed to be the technique of choice for the relief of pain in labor. Multiple adverse neurological effects have been reported, one of which is the so-called Horner syndrome (ptosis, myosis, anhidrosis). Its evolution is usually benign and does not require specific management, except clinical monitoring for the more than probable cephalic spread of local anesthetic. Most of the cases that exist in the literature are isolated; in our work we present a series of 3 clinical cases and review the pathogenesis and management in the obstetric patient.

La analgesia epidural supone la técnica de elección para el alivio del dolor del parto. Se han descrito múltiples efectos adversos a nivel neurológico, uno de ellos es el llamado Síndrome de Horner (ptosis,miosis, anhidrosis), suele presentar evolución benigna y no requiere manejo especifico, salvo vigilancia clínica por la más que probable difusión cefálica del anestésico local. La mayor parte de los casos existentes en la literatura son aislados, en nuestro trabajo presentamos una serie de 3 casos clínico y repasamos su etiopatogenía y manejo en la paciente obstétrica.

Horner syndrome was first described in 1879 by Swiss ophthalmologist Johann Friedrich Horner. It is characterized by the presence of myosis, ptosis, and anhidrosis, with or without enophthalmos.1 Its primary cause is the ipsilateral interruption of the sympathetic nerve fibers that innervate the pupil, the upper eyelid lifter muscle, and the facial region.2

Any obstacle that affects this neuronal region, from the origin to the last synapse, can lead to this clinical picture. Acquired causes are the most frequent, as are iatrogenic causes due to neuraxial anesthesia, and, in certain populations (such as the obstetric population), the incidence increases considerably due to anatomical and physiological changes that occur. Epidural analgesia is considered the analgesic technique of choice for labor.3 Horner syndrome associated with epidural analgesia for labor was described by Kepes in 1972. Its incidence is estimated at between 0.4 and 4%.4–7

In our study, we present a series of three clinical cases of Horner syndrome in pregnant patients that received epidural analgesia for labor. We also review the physiopathology, implications, and management of the labor.

Clinical caseThe technique used in the three cases is described as follows: we use an 18 gauge Touhy needle. The space chosen was L3–L4 with an intervertebral approach. Once the epidural space was located through the loss of resistance to saline technique, a multi-perforated epidural catheter was place 4cm within the space. The technique was applied in all cases without incident. After the administration of one bolus of 0.16% ropivacaine with 1μm/ml of fentanyl, the perfusion of anesthetic at the same concentration was initiated. As a test dose, we used 4ml of bupivacaine at 0.25% with 1/200,000 epinephrine.

Case 127-Year-old patient in her first gestation in spontaneous labor at 38 weeks of gestation, 172cm tall and 75kg body weight, without medical antecedents of interest. A significant characteristic to highlight was a noticeable lumbar hyperlordosis. The epidural catheter was placed at 4cm dilation, after which 11ml of ropivacaine with fentanyl at the concentration described above was administered. Continuous perfusion of 10mlh−1 of the same anesthetic solution was initiated. She did not receive any supplementary boluses. After the dilation phase and 95min after the initiation of the perfusion, the patient complained of symptomatology compatible with brachial palsy. After neurological exploration, a motor deficit was observed (level 3 on the Medical Research Council scale) that included the entire upper limb, as well as unspecific soreness at the ipsilateral ocular level with evidence of ptosis, myosis, and anhidrosis compatible with Horner syndrome. The level of sensory block reached T2. After the perfusion was detained, motor and ocular clinical presentation reversed after 115min.

Case 228-Year-old patient in her first gestation in spontaneous labor at 37 weeks of gestation. 160cm tall and 55kg body weight without personal antecedents of interest. 8ml of ropivacaine and fentanyl were administered in the initial bolus followed by continuous perfusion at 8mlh−1. The patient received two supplementary boluses, first 30min after the start of perfusion, and the second 45min after the previous bolus. During the dilation phase and 80min after the last bolus, the patient described ptosis, myosis, and enophthalmos, without manifested anhidrosis. Motor deficit was not present; the sensory deficit rose to T3. The clinical presentation disappeared 130min after detaining the perfusion.

Case 332-Year-old patient in her first gestation in induced labor at 41 weeks of gestation. 155cm tall and 60kg body weight. She had chronic arterial hypertension as an antecedent of interest. An initial bolus of 9ml of ropivacain and fentanyl was administered, followed by a continuous perfusion of 8mlh−1. After 45min, and due to risk of loss of fetal wellness, the decision was made to initiate an emergency cesarean section. For this, 9ml of 2% lidocaine was administered. After the beginning of the cesarean section, a clinical presentation suggesting Horner syndrome was observed (see Fig. 1) only 15min after the administration of the anesthetic bolus of lidocaine. No motor symptoms were reported. The sensory level reached metamere T2. After 95min of observation, the clinical presentation disappeared without further measures.

After the clinical diagnosis from evidence of ptosis, myosis, enophthalmos, and anhidrosis, an neurological (sensory level and motor function) and cardiorespiratory (continuous monitoring of blood oxygen saturation with pulse oximetry, electrocardiography, and non-invasive blood pressure) exploration was initiated.

The perfusion of local anesthetic was detained in all the cases. None of the patients presented with cardiorespiratory complication, maintaining a heart rate of around 70beats per minute, average blood pressure above 65mm/hg, and blood oxygen saturation above 95% with no need for supplementary oxygen. The clinical presentation reversed in a variable time after perfusion was stopped.

There were no neonatal repercussions in any of the cases presented.

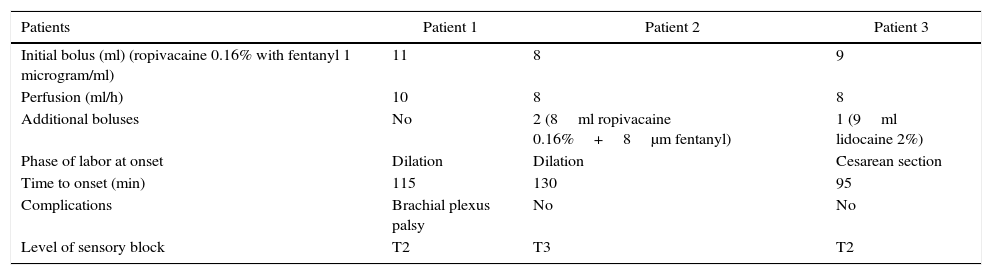

Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics of the patients.

Clinical description of each of the cases.

| Patients | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial bolus (ml) (ropivacaine 0.16% with fentanyl 1 microgram/ml) | 11 | 8 | 9 |

| Perfusion (ml/h) | 10 | 8 | 8 |

| Additional boluses | No | 2 (8ml ropivacaine 0.16%+8μm fentanyl) | 1 (9ml lidocaine 2%) |

| Phase of labor at onset | Dilation | Dilation | Cesarean section |

| Time to onset (min) | 115 | 130 | 95 |

| Complications | Brachial plexus palsy | No | No |

| Level of sensory block | T2 | T3 | T2 |

The clinical presentation of Horner syndrome is inconspicuous and can go unnoticed, with some authors affirming that it can go unobserved in 75% of births by cesarean section that use this anesthetic method.5 For the majority of our patients, the presentation was subtle with partial ptosis.

Multiple reasons have been described for explaining the physiopathology. The majority of authors agree that, for the syndrome to present, a cephalic spread of the local anesthetic is necessary, leading to an interruption of the sympathetic chain from C8 to T1 before entering the superior cervical ganglion. In gestating patients, a series of anatomical changes occur that favor the spread of the anesthetic to the upper levels: abdominal hyper-pressure from the gravid uterus, uterine contractions, and dilation of the epidural venous plexus that reduces such space. The higher sensitivity of the sympathetic fibers to the local anesthetic allows for their block while maintaining sensory and motor fibers. However, in some cases, like the one described above, it can be associated with brachial plexus palsy in a probable relationship with spread toward the subdural or subarachnoid space.8,9

There are anatomical variations that facilitate the ascension of local anesthetic, like the presence of fibrous septae in the epidural space, lumbar hyperlordosis, scoliosis, spondylolisthesis, post-surgical adhesions, and repeated epidural punctures. One of the patients presented with a noticeable lumbar hyperlordosis while the rest of the cases showed the normal anatomy of a pregnant woman.

Other theories that explain this phenomenon go beyond the changes that occur in the pregnant patient, arguing for an erroneous placement of the epidural catheter either in the subdural space or its paravertebral migration. The insertion of the catheter at the subdural level leads to the spread of the anesthetic to the subarachnoid space, leading to a sensory block that affects the more cephalic metameres for the volume and concentration used with a variable motor effect and even cardiorespiratory arrest.10 Due to the benign evolution, the subdural situation was not ruled out with radiology. It is probable that using multi-perforated catheters facilitates placement, albeit partially, in this space, since some orifices are at the epidural level and others at the subdural level.

The decubitus lateral position during puncture and the increase in sensitivity of pregnant patients to local anesthetics due to progesterone are other factors to take into account. All of the punctures in our patients were performed in a sitting position.

The anesthetic used does not seem to influence incidence, as in our series the syndrome appeared with both the administration of ropivacaine and lidocaine, although in the latter case, the latency and recovery times were considerably reduced. The repeated administration of the dose of local anesthetic can favor its cephalic spread. In two of the cases, additional boluses (i.e. apart from the initial one) were administered, one at the time of the cesarean section and the other during the dilation phase due to patient request (pain>4 measured on the visual analog scale). One of the cases had the clinical presentation with continuous perfusion and without additional boluses. The volume of local anesthetic administered in the initial bolus was calculated at around 0.5–1ml per metamere to be covered in function of the stage of labor.

The presentation of Horner syndrome is, in most cases, self-limiting and resolves itself in an average time of 215min, with a relatively benign course.11 Generally, heart and respiratory stability is maintained, with maternal hypotension being infrequent. In the patients in our study, the clinical presentation disappeared in an average time of 113min. All patients maintained cardiorespiratory stability.

However, despite their good evolution, the presence of the syndrome tells us of a sympathetic block that reaches thoracic levels with a potential risk of cardiorespiratory collapse. Therefore, surveillance of the patient is essential, especially if we opt to maintain the epidural catheter. With the least suspicion of an effect on the patient, the perfusion of local anesthetics should be withdrawn, and close monitoring of the maternal-fetal state should be performed.12 We opted for withdrawing the perfusion in those patients that presented with the syndrome in the dilation phase, evaluating the potential risk of maternal-fetal effects, as previously mentioned. The patient that suffered the episode during the cesarean section after the epidural bolus remained under close monitoring without complications in the recovery.

When this complication occurs, an exhaustive neurological exploration is recommended. Performing complementary tests is not recommended systematically; these are reserved for patients in which the clinical picture persists more than 12–24h in order to rule out other causes (Pancoast tumor, carotid artery dissection).13,14

The majority of the series described in the literature are isolated cases.2–13 Few case series affecting multiple patients have been published.15 The main reason for this is probably the low degree of suspicion and the underdiagnosis of the syndrome—in other words, it has to be actively looked for. Despite its favorable prognosis, it can directly indicate a cephalic spread of local anesthetic to potentially dangerous levels. Therefore, observation and surveillance until the complete disappearance of the clinical presentation, along with suspension of perfusion of local anesthetic, are essential to its management.

FinancingThe authors did not receive sponsorship to carry out this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Sánchez E, Vadillo JM, Herrera-Calo P, Marenco de la Fuente ML. Sindrome de Horner tras analgesia epidural para el parto. Informe de 3 casos. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2016;44:170–173.