In up to 50% of cases, inguinal hernia repair is associated with chronic post-surgical pain, which can be a cause of disability in a proportion of patients.

ObjectiveTo estimate the incidence of chronic post-surgical pain and its associated factors in patients taken to inguinal hernia repair.

Materials and methodsObservational follow-up study in a cohort of patients. Social, demographic and personal background information was obtained; the incidence and intensity of acute and chronic post-operative pain was determined; and the factors associated with the development of chronic pain were evaluated. Associations were determined in accordance with the nature of the variables. A linear regression was used to assess the role of confounding factors.

ResultsOverall, 108 patients were analysed, and of them, 27.8% (n=30) had chronic post-surgical pain. The multivariate analysis showed that the use of general anaesthesia and uncontrolled pain 15 days after surgery were associated with a higher risk of developing this condition. In contrast, diclofenac administration was protective.

DiscussionChronic post-surgical pain is frequent in this type of surgery. According to this study, the use of peri-operative analgesia together with pain prevention and management within the first post-operative weeks help prevent the development of chronic post-surgical pain. General anaesthesia may increase the risk. Similar studies conducted at a larger scale could help identify other associated factors.

La herniorrafia inguinal se asocia hasta en un 50% de los casos a dolor crónico posoperatorio, y en algunas personas puede ser incapacitante.

ObjetivoEstimar la incidencia e identificar los factores asociados al dolor crónico postoperatorio en pacientes llevados a herniorrafia inguinal.

Matriales y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional en una cohorte de seguimiento. Se obtuvo información sociodemográfica y de antecedentes personales, se determinó la incidencia e intensidad de dolor agudo posoperatorio y de dolor crónico posoperatorio, y se evaluaron los factores asociados al desarrollo de este último. Se establecieron asociaciones según la naturaleza de las variables. Mediante una regresión lineal se evaluó el papel de los factores de confusión.

ResultadosSe analizaron 108 pacientes, de los cuales 27.8% (n=30) presentaron dolor crónico posoperatorio. El análisis multivariado mostró que el uso de anestesia general y el dolor no controlado a los 15 días del postoperatorio se relacionaron con mayor riesgo de desarrollar esta entidad. La administración de diclofenaco fue en cambio un factor protector.

DiscusiónEl dolor crónico postoperatorio es frecuente luego de una herniorrafia inguinal. Según este estudio, el uso de analgesia perioperatoria y la prevención y manejo del dolor en las primeras semanas del posoperatorio, ayudan a prevenir esta entidad. La anestesia general podría aumentar el riesgo. Estudios similares realizados a una escala más grande, permitirán identificar otros factores relacionados.

Based on the criteria by Macrae and Akkaya, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) defined chronic post-surgical pain (CPSP) as pain lasting at least 2 months following the insult, after having ruled out other causes for pain and the possibility of it being the continuation of a pre-existing problem.1,2 Other authors have suggested increasing this time period to 3–6 months following surgery, which is more consistent with the most widely accepted definition of chronic pain (3 months), and allows for longer follow-up of the patient's functional status.3 In view of the above, the two-month cutoff point might correspond to a continuum between acute post-operative pain and CPSP.

Inguinal hernia repair is associated with the presence of CPSP in up to 50% of cases,2,4 with a mean of 11.5%5 reports of persistent pain even up to a year after surgery.4 However, prevalence varies according to the surgical technique, being higher in open inguinal herniorrhaphy (7.3%), as compared with laparoscopic repair (5%).6 CPSP requires early multi-disciplinary treatment, given the fact that up to 20% of patients are affected in their ability to perform their daily activities.7

Predisposing factors for CPSP are described in the literature.8–13 However, results are still contradictory, which means that the search for these associations needs to continue in order to identify those patients who are at risk of suffering from this disorder. Moreover, a search of the literature revealed that, in Colombia, there are no data available to help determine the size of the problem of persistent post-operative pain (PPP) and CPSP following inguinal hernia repair and, consequently, there is no culture among healthcare practitioners of systematically working to prevent this disorder.

The objective of this study is to estimate the incidence of CPSP and its associated factors in patients taken to inguinal herniorrhaphy at Hospital Universitario Mayor (HUM) and Hospital Universitario Barrios Unidos (HUBU) – Mederi. This will provide data to help assess the size of the problem in our setting and implement actions that may have an impact on the quality of life of our patients.

MethodologyObservational follow-up cohort study. The study was first approved by the Ethics Committees of Universidad del Rosario and Méderi. It included patients over 18 years of age, ASA I, II and III, scheduled for unilateral or bilateral inguinal herniorrhaphy at HUM and HUBU – Mederi, during the time period between February and August 2014. The patients agreed to participate in the study and signed the relevant informed consent. Excluded were patients with a history of sensory-motor disability that prevented them from responding a sociodemographic questionnaire, rating pain intensity and/or answering the post-operative telephone survey; patients with chronic pelvic pain of gynaecological origin; and pregnant women. Patients were recruited sequentially during the study period. Before the surgical procedure, they were given a questionnaire consisting of sociodemographic and personal variables. After the surgery, the intensity of acute post-operative pain was assessed in the recovery room using the visual analogue scale (VAS). Additional relevant data were taken from the electronic clinical record in order to assess the presence of factors associated with the development of CPSP. All patients were given a telephone survey two months later in order to determine the presence or absence of pain 15 days after surgery, the development of complications, and the presence of CPSP. Additionally, pain intensity in cases of CPSP was measured during the same telephone call using the verbal pain scale. CPSP was diagnosed in cases of pain or persistent dysesthesia in the surgical area, whether it irradiated or not to the inguinal and pubic area or to the thigh two months after the surgery, only if the pain or dysesthesia had different characteristics when compared with the pre-operative finding, if applicable. A distinction was made between the presence of CPSP and PPP according to the pain characteristics reported by the patients at the time of the post-operative call.

Statistical analysisA descriptive analysis of the data collected was performed using the SPSS software package, version 19. Normality tests were performed for the quantitative variables. The incidence of APSP and CPSP was estimated. The chi square was used for estimating associations, the Fisher exact test was used for qualitative variables, the Student's t test was used for variables with parametric distribution, and the Mann–Whitney U test was used for non-parametric distribution, with their respective statistical significance. Finally, a multivariate analysis was conducted including candidate variables in accordance with the Hosmer–Lemershow criterion (p<0.2), and those considered clinically relevant, in order to estimate relative risks adjusted for potential confounding variables.

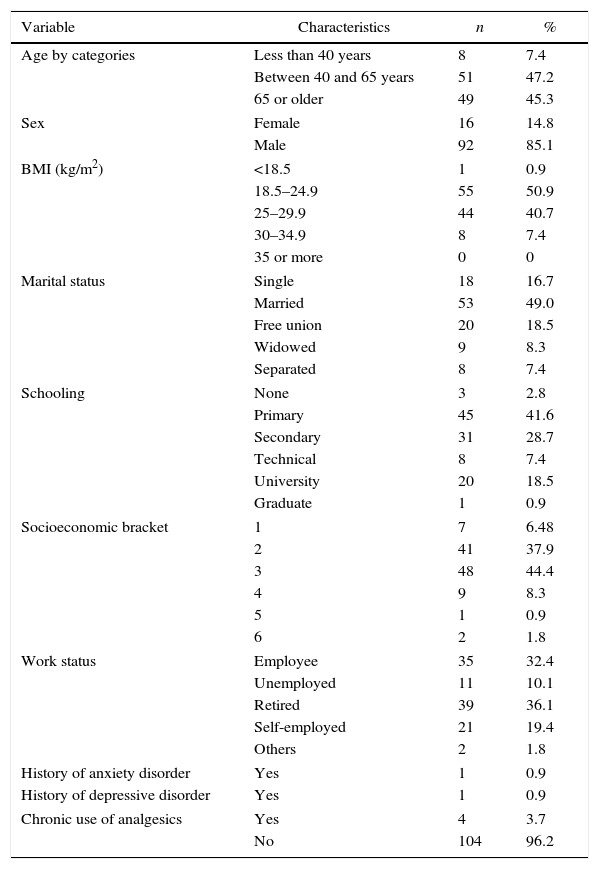

ResultsAn initial sample of 114 patients was obtained. Of these, 6 were lost to follow-up (due to change in domicile or wrong telephone number), resulting in the analysis of results for 108 patients, of which 76 (70.3%) were taken to open surgery and 32 (29.6%) to laparoscopic surgery. No mortality was reported. Mean age was 61 years±14.6, with a range between 26 and 92 years of age. The majority of patients were males (n=92, 85.1%), with normal BMI (24.8kg/m2±3.1, minimum 17.26, maximum 31.79). Only one patient in the sample had a history of depression and anxiety at the time of inclusion in the study. Table 1 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample analysed.

Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variable | Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age by categories | Less than 40 years | 8 | 7.4 |

| Between 40 and 65 years | 51 | 47.2 | |

| 65 or older | 49 | 45.3 | |

| Sex | Female | 16 | 14.8 |

| Male | 92 | 85.1 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | <18.5 | 1 | 0.9 |

| 18.5–24.9 | 55 | 50.9 | |

| 25–29.9 | 44 | 40.7 | |

| 30–34.9 | 8 | 7.4 | |

| 35 or more | 0 | 0 | |

| Marital status | Single | 18 | 16.7 |

| Married | 53 | 49.0 | |

| Free union | 20 | 18.5 | |

| Widowed | 9 | 8.3 | |

| Separated | 8 | 7.4 | |

| Schooling | None | 3 | 2.8 |

| Primary | 45 | 41.6 | |

| Secondary | 31 | 28.7 | |

| Technical | 8 | 7.4 | |

| University | 20 | 18.5 | |

| Graduate | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Socioeconomic bracket | 1 | 7 | 6.48 |

| 2 | 41 | 37.9 | |

| 3 | 48 | 44.4 | |

| 4 | 9 | 8.3 | |

| 5 | 1 | 0.9 | |

| 6 | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Work status | Employee | 35 | 32.4 |

| Unemployed | 11 | 10.1 | |

| Retired | 39 | 36.1 | |

| Self-employed | 21 | 19.4 | |

| Others | 2 | 1.8 | |

| History of anxiety disorder | Yes | 1 | 0.9 |

| History of depressive disorder | Yes | 1 | 0.9 |

| Chronic use of analgesics | Yes | 4 | 3.7 |

| No | 104 | 96.2 | |

It was found that 59.2% of the patients had pre-operative groin pain (n=64), mild in 48.4% (n=31), moderate in 42.2% (n=27), and severe in 9.3% (n=6). There were no cases of unbearable pre-operative pain. Groin pain was right-sided in 54.7% of cases (35/64), left-side in 34.3% (22/64) and bilateral in 10.9% (7/64).

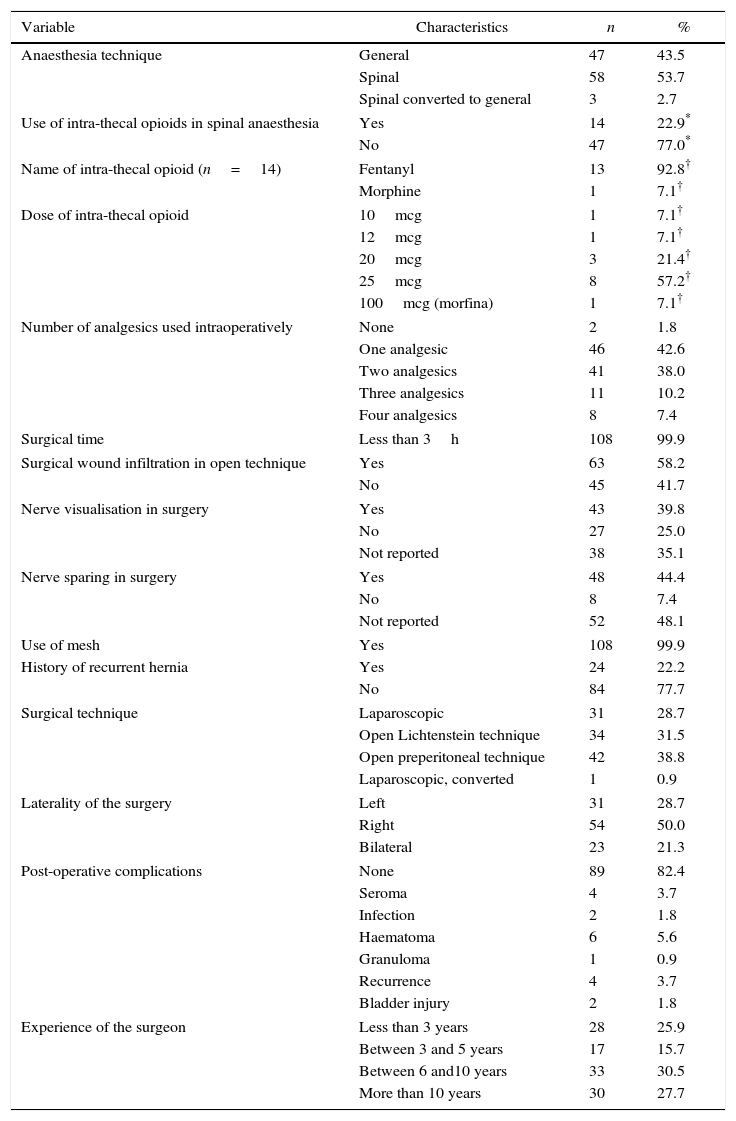

Regarding the anaesthesia technique, the majority of patients received spinal anaesthesia (n=61, 56.4%). Of those taken to open surgery, 75% received spinal anaesthesia (n=57), while all patients taken to laparoscopic hernia repair received general anaesthesia. Intra-thecal opioid was used in 22.9% of patients intervened under spinal anaesthesia (n=14); of them, 13 received fentanyl in a dose range of 10–25mcg, and one patient received a dose of 100mcg of intra-thecal morphine. One or two intra-operative analgesics were used in the majority of patients (42.6% and 38%, respectively). Regarding the details of the surgical technique, the open technique was used in 70.3% of cases (n=76), while laparoscopic herniorrhaphy was performed in 28.7% of patients (n=31). One case required conversion of the surgical technique (from laparoscopic to open). Two types of open techniques were performed: pre-peritoneal in 38.8% of cases (n=42), and Lichtenstein in 31.5% (n=34); the transabdominal pre-peritoneal technique (TAPP) was used in all cases of laparoscopic surgery. The most frequent post-operative complication was haematoma development (n=6, 5.6%). No complications were found in 82.4% of cases (n=89). Table 2 shows the anatomical and surgical variables included in the assessment.

Anaesthetic and surgical variables.

| Variable | Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anaesthesia technique | General | 47 | 43.5 |

| Spinal | 58 | 53.7 | |

| Spinal converted to general | 3 | 2.7 | |

| Use of intra-thecal opioids in spinal anaesthesia | Yes | 14 | 22.9* |

| No | 47 | 77.0* | |

| Name of intra-thecal opioid (n=14) | Fentanyl | 13 | 92.8† |

| Morphine | 1 | 7.1† | |

| Dose of intra-thecal opioid | 10mcg | 1 | 7.1† |

| 12mcg | 1 | 7.1† | |

| 20mcg | 3 | 21.4† | |

| 25mcg | 8 | 57.2† | |

| 100mcg (morfina) | 1 | 7.1† | |

| Number of analgesics used intraoperatively | None | 2 | 1.8 |

| One analgesic | 46 | 42.6 | |

| Two analgesics | 41 | 38.0 | |

| Three analgesics | 11 | 10.2 | |

| Four analgesics | 8 | 7.4 | |

| Surgical time | Less than 3h | 108 | 99.9 |

| Surgical wound infiltration in open technique | Yes | 63 | 58.2 |

| No | 45 | 41.7 | |

| Nerve visualisation in surgery | Yes | 43 | 39.8 |

| No | 27 | 25.0 | |

| Not reported | 38 | 35.1 | |

| Nerve sparing in surgery | Yes | 48 | 44.4 |

| No | 8 | 7.4 | |

| Not reported | 52 | 48.1 | |

| Use of mesh | Yes | 108 | 99.9 |

| History of recurrent hernia | Yes | 24 | 22.2 |

| No | 84 | 77.7 | |

| Surgical technique | Laparoscopic | 31 | 28.7 |

| Open Lichtenstein technique | 34 | 31.5 | |

| Open preperitoneal technique | 42 | 38.8 | |

| Laparoscopic, converted | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Laterality of the surgery | Left | 31 | 28.7 |

| Right | 54 | 50.0 | |

| Bilateral | 23 | 21.3 | |

| Post-operative complications | None | 89 | 82.4 |

| Seroma | 4 | 3.7 | |

| Infection | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Haematoma | 6 | 5.6 | |

| Granuloma | 1 | 0.9 | |

| Recurrence | 4 | 3.7 | |

| Bladder injury | 2 | 1.8 | |

| Experience of the surgeon | Less than 3 years | 28 | 25.9 |

| Between 3 and 5 years | 17 | 15.7 | |

| Between 6 and10 years | 33 | 30.5 | |

| More than 10 years | 30 | 27.7 | |

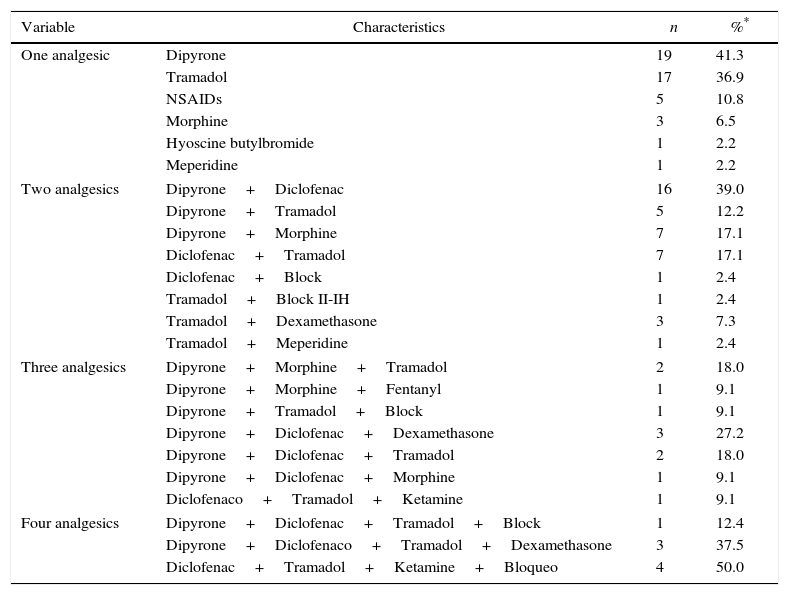

Transitional analgesia used intra-operatively was analysed in detail and it was found that when single analgesia was used, the drugs used most frequently were dipyrone and tramadol; when two analgesics were used, the most frequent combination was dipyrone+diclofenac; when three analgesics were used, the most frequent combination was dipyrone+diclofenac+tramadol. Finally, when four analgesics were used the most frequent combination used was diclofenac+tramadol+ketamine+ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric blocks (Table 3).

Transition analgesia.

| Variable | Characteristics | n | %* |

|---|---|---|---|

| One analgesic | Dipyrone | 19 | 41.3 |

| Tramadol | 17 | 36.9 | |

| NSAIDs | 5 | 10.8 | |

| Morphine | 3 | 6.5 | |

| Hyoscine butylbromide | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Meperidine | 1 | 2.2 | |

| Two analgesics | Dipyrone+Diclofenac | 16 | 39.0 |

| Dipyrone+Tramadol | 5 | 12.2 | |

| Dipyrone+Morphine | 7 | 17.1 | |

| Diclofenac+Tramadol | 7 | 17.1 | |

| Diclofenac+Block | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Tramadol+Block II-IH | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Tramadol+Dexamethasone | 3 | 7.3 | |

| Tramadol+Meperidine | 1 | 2.4 | |

| Three analgesics | Dipyrone+Morphine+Tramadol | 2 | 18.0 |

| Dipyrone+Morphine+Fentanyl | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Dipyrone+Tramadol+Block | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Dipyrone+Diclofenac+Dexamethasone | 3 | 27.2 | |

| Dipyrone+Diclofenac+Tramadol | 2 | 18.0 | |

| Dipyrone+Diclofenac+Morphine | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Diclofenaco+Tramadol+Ketamine | 1 | 9.1 | |

| Four analgesics | Dipyrone+Diclofenac+Tramadol+Block | 1 | 12.4 |

| Dipyrone+Diclofenaco+Tramadol+Dexamethasone | 3 | 37.5 | |

| Diclofenac+Tramadol+Ketamine+Bloqueo | 4 | 50.0 | |

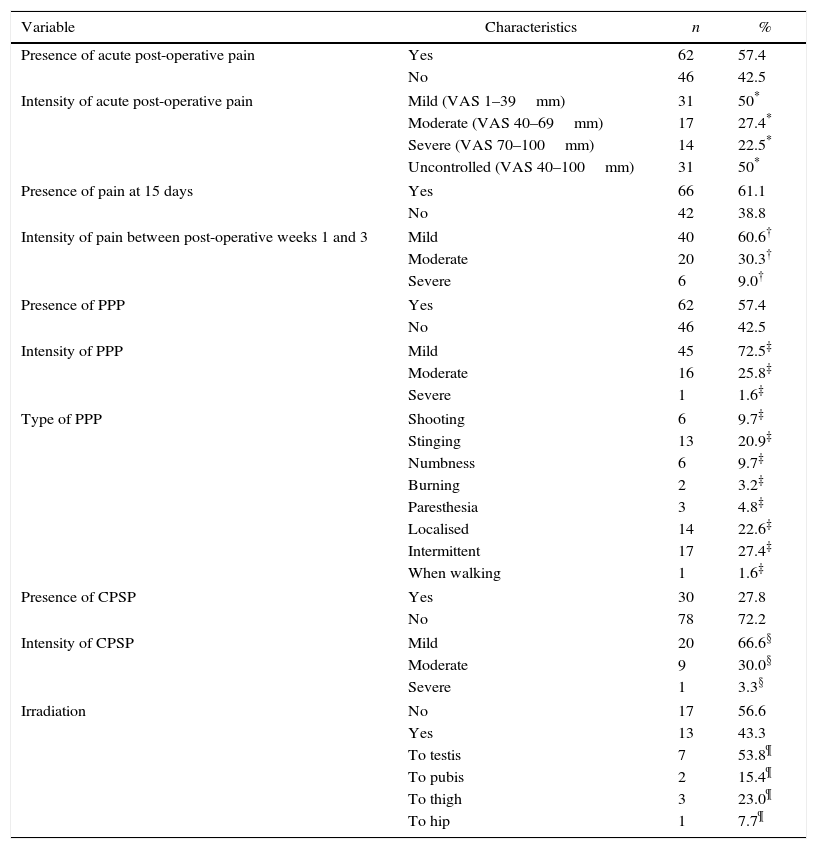

Acute post-operative pain was present in 57.4% of the patients included in the analysis (n=62). The majority described that acute pain was mild (50%, 31/62), while 50% reported uncontrolled acute post-operative pain (n=31), defined as a score of 40–100mm on the VAS. Among patients taken to open surgery, the majority experienced mild pain (30.2%), and in the laparoscopic herniorrhaphy group, the majority had acute post-operative pain of moderate intensity (28.1%). Overall, 61.1% reported pain at 15 days (n=66), of mild intensity in the majority of cases (n=40, 60.6%). When the presence of pain was assessed two months after surgery, 57.4% (n=62) reported pain in the operated area, the majority of mild intensity (n=45, 72.5%); however, 30 of the 62 cases met the diagnostic criteria for CPSP (27.8% of the total sample). Localised, intermittent pain, and pain on exertion (walking) were found not to meet the criteria of CPSP. Table 4 shows post-operative pain and its characteristics.

Post-operative pain.

| Variable | Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of acute post-operative pain | Yes | 62 | 57.4 |

| No | 46 | 42.5 | |

| Intensity of acute post-operative pain | Mild (VAS 1–39mm) | 31 | 50* |

| Moderate (VAS 40–69mm) | 17 | 27.4* | |

| Severe (VAS 70–100mm) | 14 | 22.5* | |

| Uncontrolled (VAS 40–100mm) | 31 | 50* | |

| Presence of pain at 15 days | Yes | 66 | 61.1 |

| No | 42 | 38.8 | |

| Intensity of pain between post-operative weeks 1 and 3 | Mild | 40 | 60.6† |

| Moderate | 20 | 30.3† | |

| Severe | 6 | 9.0† | |

| Presence of PPP | Yes | 62 | 57.4 |

| No | 46 | 42.5 | |

| Intensity of PPP | Mild | 45 | 72.5‡ |

| Moderate | 16 | 25.8‡ | |

| Severe | 1 | 1.6‡ | |

| Type of PPP | Shooting | 6 | 9.7‡ |

| Stinging | 13 | 20.9‡ | |

| Numbness | 6 | 9.7‡ | |

| Burning | 2 | 3.2‡ | |

| Paresthesia | 3 | 4.8‡ | |

| Localised | 14 | 22.6‡ | |

| Intermittent | 17 | 27.4‡ | |

| When walking | 1 | 1.6‡ | |

| Presence of CPSP | Yes | 30 | 27.8 |

| No | 78 | 72.2 | |

| Intensity of CPSP | Mild | 20 | 66.6§ |

| Moderate | 9 | 30.0§ | |

| Severe | 1 | 3.3§ | |

| Irradiation | No | 17 | 56.6 |

| Yes | 13 | 43.3 | |

| To testis | 7 | 53.8¶ | |

| To pubis | 2 | 15.4¶ | |

| To thigh | 3 | 23.0¶ | |

| To hip | 1 | 7.7¶ | |

The incidence of acute post-operative pain in the sample assessed was 57 for every 100 patients taken to inguinal hernia repair, while the incidence of CPSP was 27 for every 100.

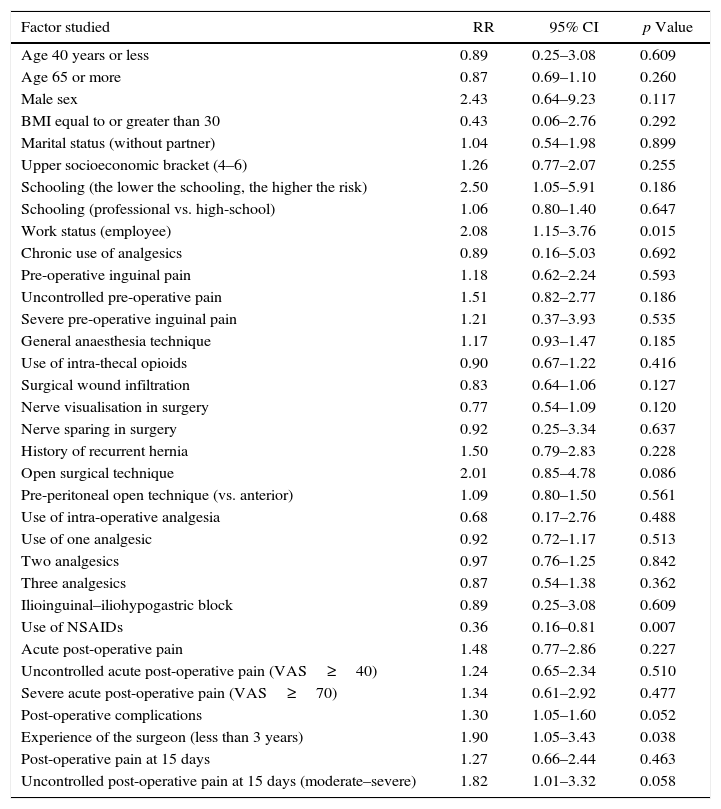

The bivariate analysis (Table 5) showed the following statistically significant associations: being a working employee was associated with a higher risk of developing CPSP (RR 2.08; 95% CI 1.15–3.76), as was also the case with the presence of post-operative complications (RR 1.3; 95% CI 1.05–1.60), a less experienced surgeon (RR 1.9; 95% CI 1.05–3.43), and uncontrolled pain after 15 days (RR 1.82, 95% CI 1.01–3.32). In contrast, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac IV was found to be associated with a lower risk (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.16–0.81). Although age was different in the comparison groups (mean of 58.3 years vs. 63.2 years in patients with and without CPSP, respectively), it was not significantly associated with the development of chronic pain (p=0.127).

Factors associated with the development of CPSP in inguinal hernia repair.

| Factor studied | RR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 40 years or less | 0.89 | 0.25–3.08 | 0.609 |

| Age 65 or more | 0.87 | 0.69–1.10 | 0.260 |

| Male sex | 2.43 | 0.64–9.23 | 0.117 |

| BMI equal to or greater than 30 | 0.43 | 0.06–2.76 | 0.292 |

| Marital status (without partner) | 1.04 | 0.54–1.98 | 0.899 |

| Upper socioeconomic bracket (4–6) | 1.26 | 0.77–2.07 | 0.255 |

| Schooling (the lower the schooling, the higher the risk) | 2.50 | 1.05–5.91 | 0.186 |

| Schooling (professional vs. high-school) | 1.06 | 0.80–1.40 | 0.647 |

| Work status (employee) | 2.08 | 1.15–3.76 | 0.015 |

| Chronic use of analgesics | 0.89 | 0.16–5.03 | 0.692 |

| Pre-operative inguinal pain | 1.18 | 0.62–2.24 | 0.593 |

| Uncontrolled pre-operative pain | 1.51 | 0.82–2.77 | 0.186 |

| Severe pre-operative inguinal pain | 1.21 | 0.37–3.93 | 0.535 |

| General anaesthesia technique | 1.17 | 0.93–1.47 | 0.185 |

| Use of intra-thecal opioids | 0.90 | 0.67–1.22 | 0.416 |

| Surgical wound infiltration | 0.83 | 0.64–1.06 | 0.127 |

| Nerve visualisation in surgery | 0.77 | 0.54–1.09 | 0.120 |

| Nerve sparing in surgery | 0.92 | 0.25–3.34 | 0.637 |

| History of recurrent hernia | 1.50 | 0.79–2.83 | 0.228 |

| Open surgical technique | 2.01 | 0.85–4.78 | 0.086 |

| Pre-peritoneal open technique (vs. anterior) | 1.09 | 0.80–1.50 | 0.561 |

| Use of intra-operative analgesia | 0.68 | 0.17–2.76 | 0.488 |

| Use of one analgesic | 0.92 | 0.72–1.17 | 0.513 |

| Two analgesics | 0.97 | 0.76–1.25 | 0.842 |

| Three analgesics | 0.87 | 0.54–1.38 | 0.362 |

| Ilioinguinal–iliohypogastric block | 0.89 | 0.25–3.08 | 0.609 |

| Use of NSAIDs | 0.36 | 0.16–0.81 | 0.007 |

| Acute post-operative pain | 1.48 | 0.77–2.86 | 0.227 |

| Uncontrolled acute post-operative pain (VAS≥40) | 1.24 | 0.65–2.34 | 0.510 |

| Severe acute post-operative pain (VAS≥70) | 1.34 | 0.61–2.92 | 0.477 |

| Post-operative complications | 1.30 | 1.05–1.60 | 0.052 |

| Experience of the surgeon (less than 3 years) | 1.90 | 1.05–3.43 | 0.038 |

| Post-operative pain at 15 days | 1.27 | 0.66–2.44 | 0.463 |

| Uncontrolled post-operative pain at 15 days (moderate–severe) | 1.82 | 1.01–3.32 | 0.058 |

BMI: Body mass index, NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, VAS: Visual Analogue Scale.

Source: Authors.

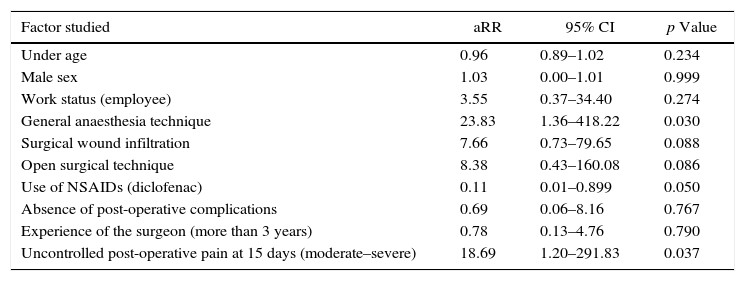

Finally, the multivariate analysis showed that general anaesthesia (aRR 23.8; 95% CI 1.36–418.22) and uncontrolled post-operative pain on day 15 (aRR 18.69; 95% CI 1.2–291.8) were risk factors with a statistically significant association. It was also found, like in the bivariate analysis, that the use of NSAID-type transitional analgesia was a protective factor against the development of CPSP (0.11, 95% CI 0.01–0.89) (Table 6).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with the development of chronic post-surgical pain.

| Factor studied | aRR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Under age | 0.96 | 0.89–1.02 | 0.234 |

| Male sex | 1.03 | 0.00–1.01 | 0.999 |

| Work status (employee) | 3.55 | 0.37–34.40 | 0.274 |

| General anaesthesia technique | 23.83 | 1.36–418.22 | 0.030 |

| Surgical wound infiltration | 7.66 | 0.73–79.65 | 0.088 |

| Open surgical technique | 8.38 | 0.43–160.08 | 0.086 |

| Use of NSAIDs (diclofenac) | 0.11 | 0.01–0.899 | 0.050 |

| Absence of post-operative complications | 0.69 | 0.06–8.16 | 0.767 |

| Experience of the surgeon (more than 3 years) | 0.78 | 0.13–4.76 | 0.790 |

| Uncontrolled post-operative pain at 15 days (moderate–severe) | 18.69 | 1.20–291.83 | 0.037 |

NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents.

Source: Authors.

Inguinal herniorrhaphy is a frequent surgical procedure that has been associated with CPSP, affecting quality of life and creating disability in the patient and costs for the health system. This study found that 27.8% of the patients reported post-operative pain consistent with the criteria for CPSP. Of them, 30% reported moderate pain and 3.3% reported severe pain. These values are consistent with other reports.2,4 The reason why some patients develop chronic pain is unknown, and a significant part of the pathophysiology of this condition is based on theoretical assumptions. In 2013, Ronal Deumens described cellular, molecular and clinical factors in an attempt at finding the best treatment based on the etiological mechanism(s).2

Although a cutoff point of 2 months was used in this study for defining CPSP, the characteristics of the pain in the intervened inguinal area was analysed in other to distinguish between PPP and CPSP. The analysis showed that 30 out of 62 patients met the criteria for neuropathic-type pain, which points more towards chronic pain. These results support statements by other authors who suggest extending follow-up 3–6 months after surgery. This is more consistent with the most widely accepted definition of chronic pain at the present time (3 months), considering that it allows for longer follow-up of the patient's functional status.3 If this were applied to the subjects included in this study, the incidence of CPSP might increase, given that close to half of the patients who experienced post-operative pain two months after surgery had pain of somatic characteristics. The persistence of this symptom could lead to central sensitisation, triggering CPSP per se.

This article describes factors associated with chronic post-surgical pain in 108 patients taken to open or laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair in two teaching hospitals in the city of Bogotá. The multivariate analysis showed that general anaesthesia is a risk factor for the development of CPSP. A study by Callesen in 2003 showed no superiority of any anaesthetic technique regarding the development of chronic pain following open inguinal hernia repair.14 The evidence suggests that more than the general or spinal anaesthesia as a factor associated with the development of CPSP, the concomitant use of local anaesthetics (for infiltration in the surgical wound or the performance of an ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric block) is a protective factor against the development of chronic pain following inguinal herniorrhaphy.15 Spinal anaesthesia has been found to be protective against the development of chronic pain in patients taken to other surgical procedures such as hysterectomy or caesarean section. One possible explanation is that central impulse blockade is powerful in spinal anaesthesia, something that does not happen under general anaesthesia.16,17 However, the finding in this study that general anaesthesia is a risk factor for the development of CPSP must be interpreted with caution. This finding about general anaesthesia may correlate with preferences of the attending anaesthetist for cases of larger size hernias, or with patients who do not cooperate and might be at a higher risk of developing CPSP, but not with the type of anaesthesia per se.

There was a statistically significant association between pain severity after 15 days and the presence of CPSP, the frequency being higher in patients with uncontrolled pain (moderate or severe), finding that is consistent with the literature. Franneby et al. found that the persistence of pain in the operated inguinal area between the first and the fourth week after the procedure is a predictive factor of persistent pain one year after inguinal hernia repair (9% vs. 3%, p<0.05, and 24% vs. 3%, p<0.001, respectively).10 The above is supported by the pathophysiology of CPSP, where the persistence of pain eventually leads to the development of peripheral neuroplasticity mechanisms that perpetuate the painful picture.18

Finally, the use of NSAIDs like diclofenac was protective against the development of CPSP in this study. The use of perioperative analgesia is based on the assumption that there is a disruption in the peripheral transmission of painful signals and, consequently, central sensitisation, reducing the risk of developing CPSP.19 However, the use of NSAIDs has not been shown to have a significant impact on the incidence or severity of persistent post-operative pain.20 The findings in the study could be explained to the extent that diclofenac was the drug most frequently used in combination with other agents as part of peri-operative multi-modal analgesia, and more than the use of specific drugs, their combination is the current recommendation for the prevention and management of acute post-operative pain21 and, consequently, CPSP.

This is the first local and national study on this topic, with stringent follow-up of patients two months after surgery. The study is highly relevant because it provides a perspective on the behaviour of CPSP following inguinal hernia repair in our setting. It has the inherent weaknesses of observational studies which require caution when it comes to making causal associations and extrapolations of the results to other populations. Perhaps due to the sample size, the study lacked sufficient power to find associations with other factors described in the literature. Larger studies with greater scope are required in order to identify other factors related to the development of chronic pain following inguinal hernia repair.

ConclusionsCPSP associated with inguinal herniorrhaphy is a frequent problem in our setting and, consequently, it requires actions designed to mitigate it. According to this study, the use of general anaesthesia may increase the risk of developing CPSP following inguinal hernia repair. Moreover, the use of intra-operative analgesia could lower the incidence of CPSP. It is recommended to implement specific evidence-based management protocols for this surgery at an institutional level in order to allow efficient management of acute post-operative pain and persistent pain during the first few weeks after the surgery and lead to a lower incidence of CPSP. Such protocols should include a programme designed to create awareness among surgeons and anaesthetists together with an education programme addressed to patients and families. Larger studies of this type may allow to identify additional factors and lead to actions designed to impact the prevention and management of CPSP.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

FundingThere are no sources of funding to declare.

Please cite this article as: Chinchilla Hermida PA, Baquero Zamarra DR, Guerrero Nope C, Bayter Mendoza EF. Incidencia y factores asociados al dolor crónico posoperatorio en pacientes llevados a herniorrafia inguinal. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2017;45:291–299.