Timely recognition of perioperative risk variables helps predict morbidity and mortality frequency, as well as adopt measures to reduce complications. Several risk scores have been developed for this purpose in patients with cardiovascular disease.

ObjectiveTo determine the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of the Goldman, Detsky and Lee cardiac risk indices for non-cardiac surgery.

MethodsObservational, analytical, longitudinal prospective study of the total number of patients with cardiovascular disease undergoing non-cardiac surgery between January 2011 and January 2013 at Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenech in Camagüey. The sample consisted of 88 patients included in the universe of patients who met the inclusion criteria. The variables studied were: age, gender, type of surgery, type of complication, and the presence or absence of complications in relation to the risk assessed on the basis of the Goldman, Detsky and Lee indices. The sensitivity, specificity and predictive value test was applied.

ResultsThere was a predominance of males in patients over 70 years of age coming for orthopaedic surgery; cardiac arrhythmia was the main complication. High-risk patients were a frequent finding and the majority suffered complications.

ConclusionsThe Goldman and Detsky indices showed high sensitivity and specificity, while the Lee index showed higher positive predictive value. However, the three predictive indices must be applied in order to optimize cardiac risk stratification in non-cardiac surgery.

Reconocer oportunamente las variables de riesgo perioperatorio permite predecir la frecuencia de morbimortalidad, así como tomar medidas a fin de reducir complicaciones, para ello se han creado varias escalas de riesgo en pacientes portadores de enfermedad cardiovascular.

ObjetivoDeterminar la sensibilidad, especificidad y los valores predictivos de los índices de riesgo cardíaco de Goldman, Detsky y Lee para cirugía no cardíaca.

MétodoSe realizó un estudio observacional, analítico, longitudinal y prospectivo del total de pacientes portadores de enfermedad cardiovascular con enfermedad quirúrgica no cardíaca en el período comprendido de enero del 2011 a enero del 2013, en el Hospital Universitario Manuel Ascunce Domenech de la ciudad de Camagüey. La muestra estuvo constituida por 88 pacientes comprendidos en el universo que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión. Las variables estudiadas fueron: edad, sexo, tipo de cirugía, tipo de complicación, y la presencia o no de estas en relación con el riesgo catalogado según los índices de Goldman, Detsky y Lee. Se aplicó prueba de sensibilidad, especificidad y valores predictivos.

ResultadosPredominaron los pacientes mayores de 70 años, el sexo masculino, la cirugía ortopédica; la arritmia cardíaca fue la principal complicación. Fue frecuente encontrar pacientes de alto riesgo, en los cuales la mayoría sufrieron complicaciones.

Conclusionesel índice de Goldman y Detsky mostraron alta sensibilidad y especificidad; y el índice de Lee mayor valor predictivo positivo. No obstante, deben aplicarse los tres índices predictivos para lograr una óptima estratificación del riesgo cardíaco en cirugía no cardíaca.

Cardiovascular disease is the primary cause of death in Cuba and in the world.1 As far as the practice of surgery is concerned, anaesthetists and surgeons alike are faced with an increasing number of elderly patients with underlying cardiovascular disease.2,3 The incidence of myocardial ischaemia in high-risk patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery is close to 40% during the perioperative period.4,5 The incidence of myocardial infarction and death during non-cardiac surgery ranges between 1% and 5%.6–8

These facts have led researchers and physicians to focus on the study of perioperative cardiovascular risk in order to avoid or reduce the occurrence of cardiovascular complications.9,10 In this regard, the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have created the Guidelines for Cardiovascular Assessment and Perioperative Care, which offer a sound basis for the stratification of surgical patients using specific cardiovascular risk factors and functional status assessment. They propose a series of decision-making algorithms related to the workup and preoperative management of these patients.11–13

Timely recognition of the cardiovascular status and identification of risk factors that may adversely affect the patient during surgery help stratify individual risk. This will be taken into consideration for deciding on the convenience or not of the surgery, the diagnostic and therapeutic plan, and other perioperative actions in order to try to avoid the occurrence of any serious cardiovascular complications.14–17

To achieve this goal, several preoperative assessment scales are available to help predict the risk of cardiovascular complications.18–22 Since the 1960s, efforts have been made to establish and unify clinical data that may help predict the risk of coronary events in patients undergoing surgery, using univariate and multivariate analyses such as the Goldman23,24, Detsky25 and Lee26,27 indices.

If a multifactorial cardiac risk index with a high predictive power is an effective tool to anticipate complications and adverse events in cardiac patients undergoing urgent non-cardiac surgery, then it can be used to optimize perioperative management and lead to more reassuring postoperative outcomes.

Our objective is to determine the sensitivity, specificity and predictive values of these three multifactorial cardiac risk indices for non-cardiac surgery.

MethodsWe conducted an observational, analytical, longitudinal and prospective study of the total number of patients with cardiovascular disease and non-cardiac surgical pathology seen between January 2011 and January 2013 at Hospital Manuel Ascunce Domenech in the city of Camagüey, in order to determine the predictive value of the Goldman, Detsky and Lee multifactorial cardiac risk indices in non-cardiac surgery.

UniverseThe total number of patients with cardiovascular disease scheduled for urgent non-cardiac surgery.

SampleAll of the patients in the universe who met the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria for the sample- •

Patients over 30 years of age.

- •

Patients with underlying cardiovascular disease undergoing non-cardiac surgical procedures.

- •

Urgent surgery.

- •

Patients in whom the quantitative assessment of each of the risk indices was not performed due to the lack of some clinical or paraclinical information required for scoring.

- •

Patients in whom it was not possible to determine whether there were any intraoperative or postoperative complications.

Age, gender, type of surgery, incidence and type of complications, risk stratification according to the Goldman, Detsky and Lee indices, relationship between the risk and the complications, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values of the three cardiac risk indices.

Operational definitionsHigh risk: Patients with a Goldman score greater than 12 points, Detsky greater than 15, and Lee greater than 2 points.

Low risk: Patients with a Goldman score between 0 and 12 points, Detsky lower than or equal to 15, and Lee lower than or equal to 2 points.

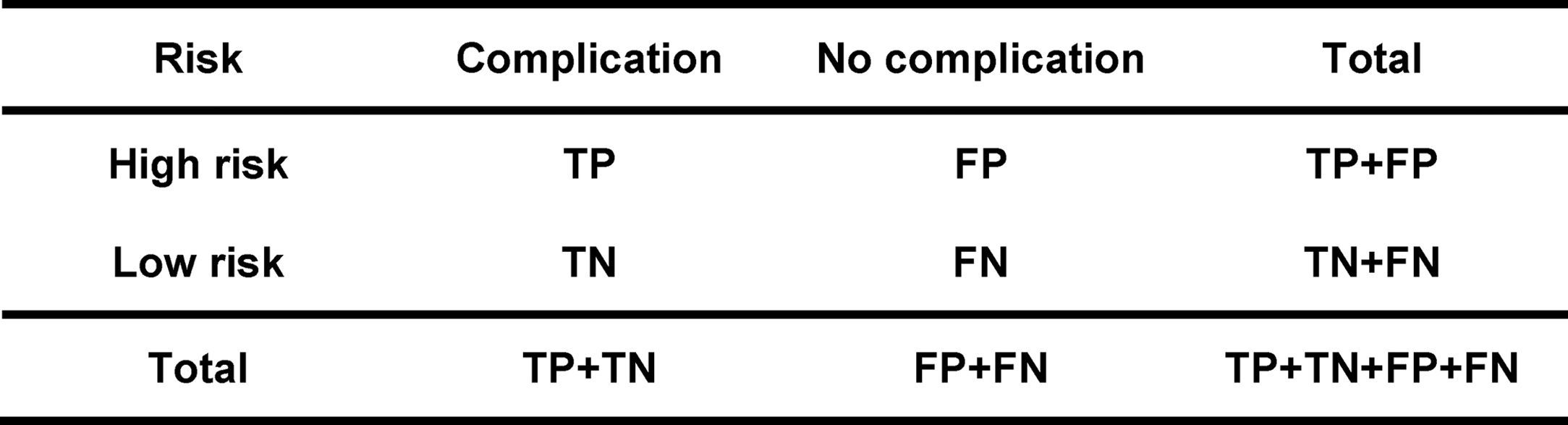

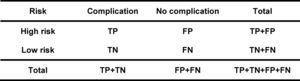

True positive (TP): Set of patients correctly predicted as being high risk.

False positive (FP): Set of patients wrongly predicted as high risk.

True negative (TN): Set of patients wrongly predicted as low risk.

False negative (FN): Set of patients correctly predicted as being low risk.

Sensitivity (S): Number of patients correctly predicted as being high risk (high probability of complications) out of the total high-risk patients (those who actually had complications). Expressed as percentage (S=TP/TP+TN).

Specificity (Sp): Number of patients correctly predicted as low risk (low probability of complications) out of the total low risk patients (those who actually did not have complications). Expressed as percentage (Sp=FN/FP+FN).

Positive predictive value (PPV): Number of patients correctly predicted as high risk (high probability of complications) out of the total number of patients predicted as high risk. Expressed in percentage (PPV=TP/TP+FP).

Negative predictive value (NPV): Number of patients correctly predicted as low risk (low probability of complications) out of the total number of patients predicted as low risk. Expressed in percentage (NPV=FN/FN+TN).

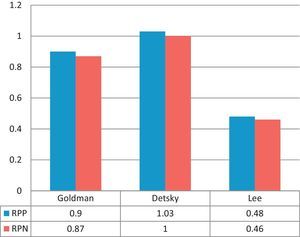

Positive probability ratio (PPR): It is the result of dividing (quotient) the probability of a high cardiovascular risk patient presenting cardiac complications by the probability of a low cardiovascular risk patient presenting cardiac complications (sensitivity/1−specificity).

Negative probability ratio (NPR): It is the result of dividing (quotient) the probability of a high cardiovascular risk patient not presenting cardiac complications by the probability of a low cardiovascular risk patient not presenting cardiac complications (1−sensitivity/specificity).

Data collectionData were obtained using a data collection model. The primary registry model was developed in accordance with criteria from experts in information systems and anaesthesiology, adapting it according to the proposed objectives. Patients with underlying cardiac disease coming for urgent surgery were identified by means of preoperative assessment, and risk stratification was made using the scales mentioned above, according to the scores. Patients were followed during the postoperative period until their hospital discharge or death, in order to determine if there were any complications, including their severity, and the findings were recorded in the primary registry or survey model. No additional preoperative pharmacological interventions were used, because the goal was to show evidence of the real risk of the underlying cardiac disease and the non-cardiac procedure.

Processing of the informationThe collected data were processed using the SPS statistical software package for Windows 10.0; descriptive and inferential statistics were used; the sensitivity, specificity, predictive value and probability ratio tests were applied to the three cardiac risk indices, with a 95% confidence interval (CI). The results were expressed in the form of tables and figures.

Ethical considerationsResearch is the main source of evidence on treatment efficacy. Consequently, national and international professional associations have created guidelines for research on healthy and diseased individuals using different deontological and legal codes. We considered the Nuremberg Code, which focuses on the rights of subjects participating in research studies and establishes consent as an essential element in human research; and the Helsinki Declaration approved in 1964 by the World Medical Assembly for the regulation of clinical research ethics on the basis of the physician's moral integrity and responsibility. The protocol for the following research was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

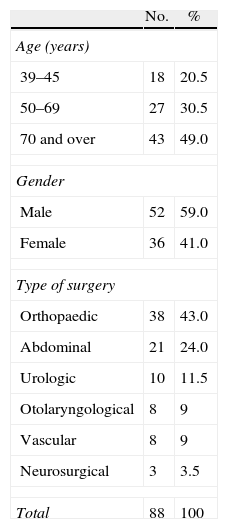

ResultsTable 1 shows patient distribution by age, gender and type of surgical procedure, with a predominance of patients over 70 years of age, representing 49%. There was a higher frequency of male patients proposed for non-cardiac procedures (59%), compared to female patients (41%). There was a high frequency of orthopaedic procedures (43%), followed by general abdominal surgery (24%).

Distribution by age, gender and type of surgical procedure.

| No. | % | |

| Age (years) | ||

| 39–45 | 18 | 20.5 |

| 50–69 | 27 | 30.5 |

| 70 and over | 43 | 49.0 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 52 | 59.0 |

| Female | 36 | 41.0 |

| Type of surgery | ||

| Orthopaedic | 38 | 43.0 |

| Abdominal | 21 | 24.0 |

| Urologic | 10 | 11.5 |

| Otolaryngological | 8 | 9 |

| Vascular | 8 | 9 |

| Neurosurgical | 3 | 3.5 |

| Total | 88 | 100 |

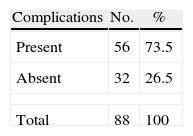

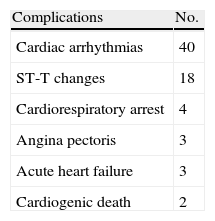

Tables 2 and 3, respectively, show the incidence of complications and the distribution of the study patients according to the type of complication during and after the surgical procedure. There was a predominance of complications in 56 patients, representing 73.5%, and the most frequent were cardiac arrhythmias, followed by ST segment changes.

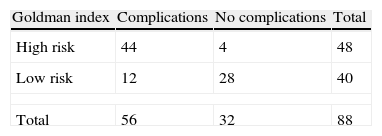

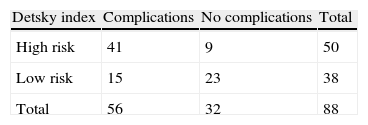

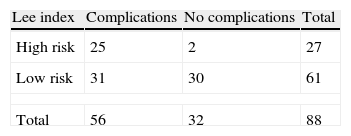

In terms of the relation among the different multifactorial cardiac risk indices and the presence or absence of complications (Tables 4–6), there is consistency with the Goldman and Detsky indices, in such a way that the highest frequency of complications was observed in high risk patients (44 and 41), and the absence of complications was seen in low risk patients (28 and 23), respectively. As for the Lee index, the presence of complications was high in low risk patients compared to the absence of complications (31 and 30), respectively (1:1 ratio), when it was expected to behave similarly to the other two indices, that is to say, that low risk should be consistent with a low frequency of complications and vice versa (Fig. 1).

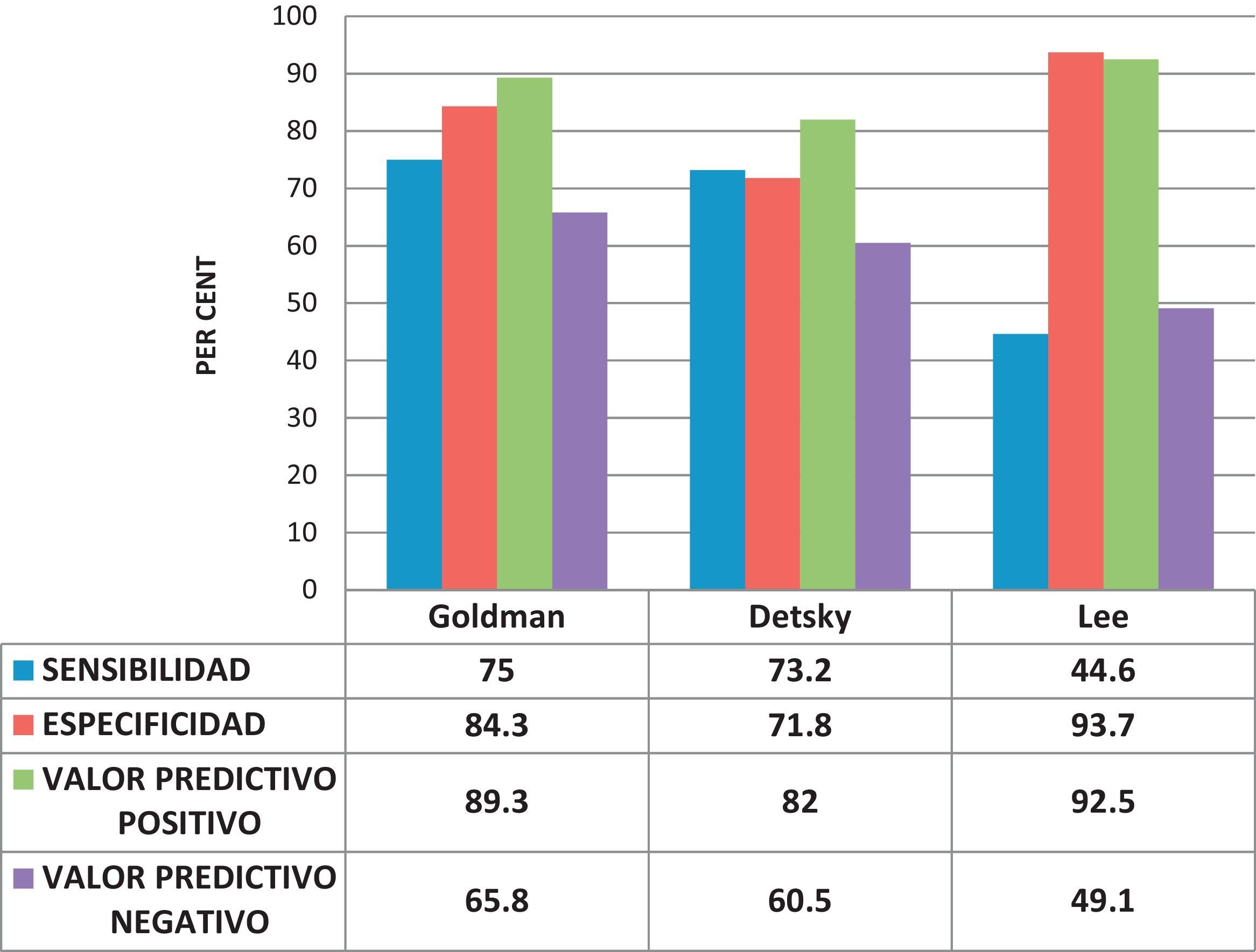

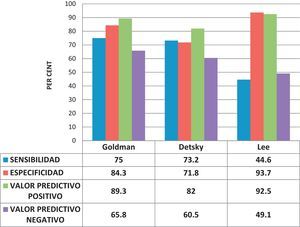

The sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive value analysis is shown in Fig. 2. The Goldman and Detsky multifactorial cardiac risk indices were similar for sensitivity, specificity and negative predictive value, reflecting their ability to predict complications in a high percentage of high risk patients; however, the Lee index showed low sensitivity and negative predictive value, with high specificity and positive predictive value results. We conclude that patients in whom the Lee index is applied may be classified wrongly as low risk and suffer cardiac complications.

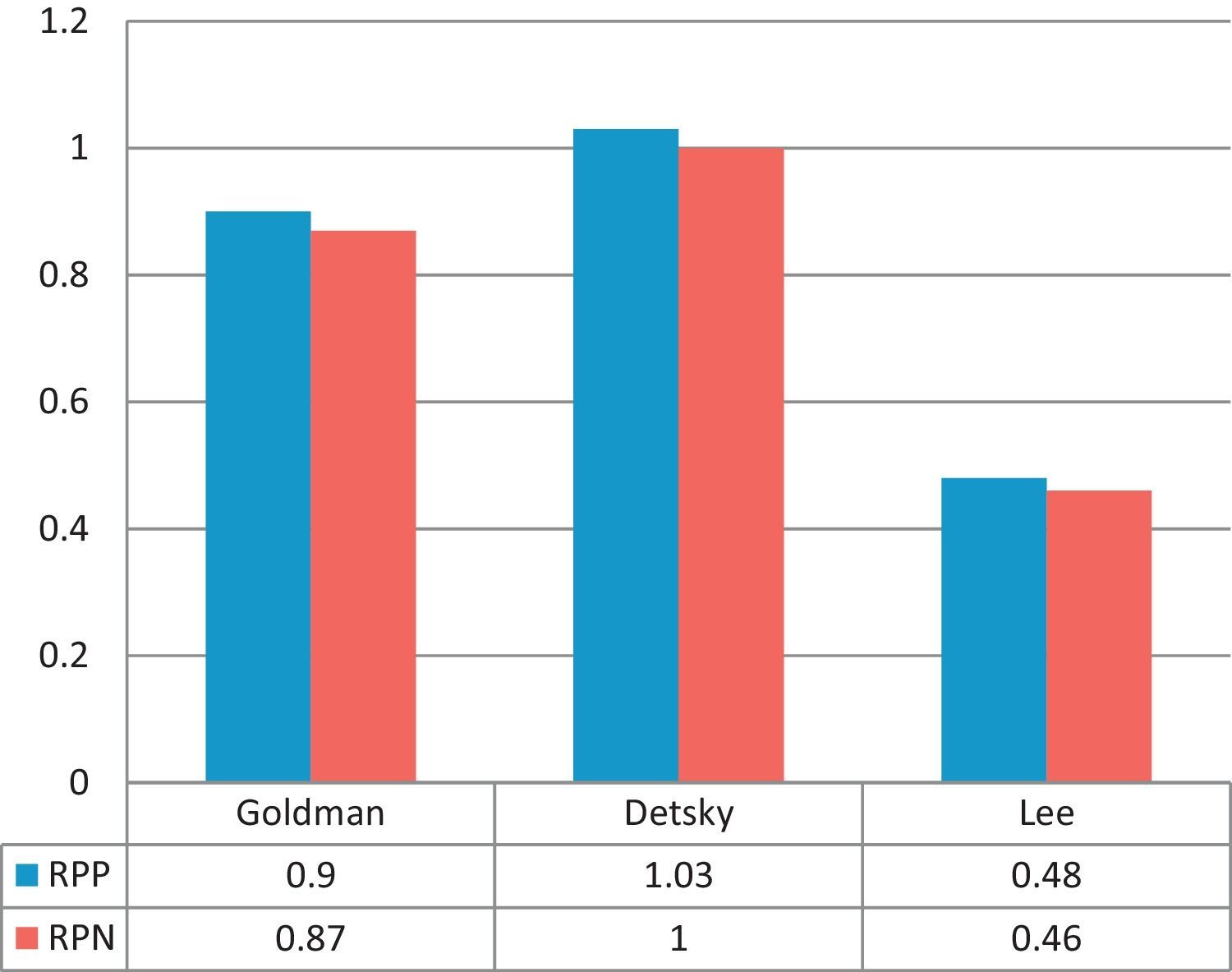

The probability or likelihood ratios compare the probability of finding the result of the diagnostic test (positive or negative) in patients with the disease or patients suffering the event of interest with the probability of finding this same result in people without the disease or the event of interest. The results of these tests are shown in Fig. 3.

DiscussionCardiac complications are among the most significant risks for patients taken to non-cardiac surgery.28,29 A prospective study published in 1977 evaluated 1001 patients of this type, older than 40 years of age, and the mean risk of cardiac complications or postoperative cardiac death was 5.8%.23,24,30 In unselected patients with a mean age of 40, acute myocardial infarction (AMI) occurred in 1.4% and cardiac death in 1%.31–33 On the other hand, with the ageing population, surgical complexity in elderly patients has increased.11,34

Atherosclerosis is the etiological factor responsible for coronary artery disease (CAD) in more than 95% of cases. Sudden death runs parallel with the occurrence of myocardial ischaemia in males after the fourth decade of life, in a proportion, according to different authors, of up to 7:1 with females. This difference is explained by the protective role of menarche in women. In the seventh decade of life, atherosclerosis affects both sexes in a 2:1 proportion.35,36

The complexity of the surgical procedure may be, in and of itself, the most important predictive factor for postoperative morbidity in many patients.37Cardiac risk may be stratified according to the type of surgical procedure to be performed. The length and type of surgery have a significant influence on the risk of perioperative cardiac complications.38,39 By definition, cardiac death or non-fatal myocardial infarction average is greater than 5% in high risk surgical procedures, between 1 and 5% in intermediate risk procedures, and less than 1% in low risk procedures.11 Most of the studies on postoperative cardiac complications have been conducted in groups of patients selected on the basis of risk. For that reason, it is difficult to generalize the results to the population requiring the majority of the surgical interventions.30,40

Intraoperative arrhythmias are among the most frequent complications in the practice of anaesthesia. Their incidence is close to 70% in non-cardiac surgery and they may reflect a serious event such as myocardial ischaemia, cerebro-vascular alteration or cardiac arrest, although they are more often benign transient disorders that may resolve spontaneously or with simple interventions.41

Sudden electrocardiographic (EKG) ST segment changes may mean, in a myocardium where flow and demand are on the limit, the manifestation of an acute coronary syndrome (infarction, angina) or plaque rupture in a patient with atherosclerotic disease. However, in a good proportion, these changes are transient and do not result in irreversible damage to the cardiac muscle or in low output state.42

In a study in 1977, Goldman et al. developed the first multifactorial risk index specifically related to cardiac complications, including nine independent risk factors.23,24 Detsky et al. updated that index in 1986, adding the CAD pretest probability, angina stratification, and time cycle for AMI and heart failure.25 The preoperative cardiac risk factor index showed a clear correlation with subsequent cardiac events: of the low risk patients, only 0.9% had cardiac events; of the high risk patients, 78% had a life-threatening cardiac event or cardiac death.23,24 The end points used by Detsky et al. in their analysis included events such as unstable angina and left ventricular insufficiency, which could complement the indicative value of preoperative risk factors in CAD assessment. The modified cardiac risk index still needs prospective revalidation.25

The Lee index,26,27 a modification of the original Goldman index, is considered by many physicians and researchers as the best of all indices available for predicting cardiac risk in non-cardiac surgery. At present, this is the model most widely used for risk assessment in non-cardiac surgery. Multifactorial indices that combine and assign relative importance to many clinical parameters are more useful than any isolated factor for determining cardiovascular risk in the individual patient, or for determining the overall morbidity risk.43,44

The Goldman index has a negative predictive value of 96.8% and, therefore, it is an excellent tool for ruling out coronary heart disease. However, with a positive predictive value of 21.6%, it is less adequate for diagnosing patients who have the disease.23,24 This latter value is not consistent with the population in our study, where the positive predictive value of the Goldman index was high (89.3%). In 1999, Lee et al.,26 reviewed the efficacy of several clinical risk factors in patients undergoing elective non-cardiac surgery. They found that the efficacy of the Goldman risk index as well as the Detsky modified cardiac risk index was similar in predicting serious cardiac complications. However, after reviewing and validating the Goldman risk index, its predictive value improved substantially.45

In a retrospective analysis of the Goldman and Detsky cardiac risk indices in elective non-cardiac surgery, an attempt was made to compare the effectiveness of these two cardiac indices when used to predict perioperative cardiovascular events; however, there were no major cardiovascular complications, precluding the comparison.46

The Goldman index showed high specificity (93.7%) and positive predictive value (90.0%) in a sample assessed by Fernández et al.43

Some important considerations about the potential usefulness of preoperative cardiac risk indices are worth noting. A low risk classification index does not exclude a patient from the perioperative cardiac risk but rather points to a low probability of a cardiac event.47 The optimum use of cardiac risk indices may be that of modifying the initial risk and not predicting the absolute risk for complications. Multifactorial indices used to assess perioperative risk in patients with underlying cardiac disease faced with a non-cardiac intervention take into consideration several clinical and paraclinical parameters that are assessed differently. Although some risk indicators are overestimated when compared to others, numerous studies have shown that they all have acceptable sensitivity and specificity47–50; however, it is important to recognize that results vary and are subject to the prevalence of cardiac disease in the type of population studied.

In this research, we conclude that the Goldman and Detsky indices showed high sensitivity and specificity, while the Lee index had a higher positive predictive value. However, all three predictive indices must be applied in order to achieve optimal cardiac risk stratification for non-cardiac surgery.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestsNone.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz HJP, Ramos HF, Tovar WLG. Sensibilidad, especificidad y valores predictivos de los índices cardiacos de Goldman, Detsky y Lee. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2014;42:184–191.