Suicidal behaviour is a global public health problem. Indigenous peoples are one of the most vulnerable populations.

ObjectiveTo establish an explanatory model of the suicidal behaviour of the indigenous peoples of the department of Vaupés.

MethodsMixed qualitative-quantitative study with the population of Vaupés. A univariate analysis of local databases, and implementation of different qualitative data collection techniques in the field, with hermeneutic analysis following guidelines proposed by other authors.

ResultsSuicidal behaviour is a problem for the indigenous peoples of Vaupés. Different explanations for these behaviours involving traditional and structural aspects are integrated in an explanatory model, which makes it possible to guide action.

ConclusionsThe explanatory model makes it possible to advance socioculturally in the appropriate way to address suicidal behaviours, and opens up new possibilities for interaction with other healthcare models.

La conducta suicida es un problema de salud pública en todo el mundo. Los pueblos indígenas son una de las poblaciones más vulnerables.

ObjetivoEstablecer un modelo explicativo de la conducta suicida de los pueblos indígenas del departamento del Vaupés.

MétodosEstudio mixto cualicuantitativo con población del Departamento del Vaupés. Análisis univariable de bases de datos locales e implementación de diferentes técnicas de recolección de datos cualitativos en campo, con el respectivo análisis hermenéutico siguiendo pautas propuestas por otros autores.

ResultadosLa conducta suicida es un problema para los pueblos indígenas del Departamento del Vaupés. Se presentan diferentes explicaciones para dichas conductas que involucran aspectos tradicionales y estructurales, los cuales se integran en un modelo explicativo que permite orientar las intervenciones.

ConclusionesEl modelo explicativo permite avanzar en la intervención de las conductas suicidas adecuada en lo sociocultural, y abre nuevas posibilidades para la interacción con otros modelos de cuidado.

Suicidal behaviour is a complex biological and sociocultural phenomenon that has been with humanity throughout its history1,2. The World Health Organization considers it a genuine "public health problem"3. It added suicidal behaviour as a priority to its Mental Health Gap Action Programme as part of its Action on Social Determinants of Health4.

Suicidal behaviour is reproduced in the region of the Americas5; hence, various strategies for its prevention have been implemented6,7. In Colombia, the data are similar to the regional and global data8,9; hence, the Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection and other related entities are pursuing different strategies for surveillance, prevention and intervention10,11.

One of the populations at highest risk of suicidal behaviour is the indigenous ethnic population. Some authors have reported a strikingly high prevalence in different regions, which has incited research to make sense of it12–16. In the case of Colombia, although the quantitative data may not be considered reliable17, various authors have taken an interest in investigating the subject18–21.

This article sought to characterise suicidal behaviour among the indigenous peoples of the Department of Vaupés along both quantitative and qualitative dimensions. It also features a proposal for understanding and intervening in suicidal behaviour.

MethodsThis study used a mixed-methods research design. General background information on the department was gathered through a literature review of the main ethnographies conducted in the Department of Vaupés as well as ethnographic work in the form of authors' field notes and journals at different points between 2012 and 201522–24.

Quantitative data related to deaths by suicide in Vaupés were obtained from the Vigilancia de la Conducta Suicida [Suicidal Behaviour Surveillance] database of the Ministry of Health of the Department of Vaupés. This database was built with an active search for cases of suicide attempts and deaths by suicide. It was prepared by professionals and technicians assigned to municipal and departmental Planes de Intervenciones Colectivas [Collective Intervention Plans]. The data underwent a univariate analysis with an emphasis on frequencies and trends.

To construct the explanatory model of suicidal behaviour, semi-structured interviews were conducted25 with departmental and municipal institution officials, as well as traditional authorities and members of the population. Survivors of suicidal behaviours in different communities were also interviewed.

An in-depth investigation of collective explanations was conducted in two peri-urban settlements where the largest numbers of suicidal behaviours in recent years had been documented. In these settlements, knowledge dialogues were established26 with the population, and social mapping27 of suicidal behaviour and body mapping28 on emotional and affective aspects were done.

The information was analysed using a hermeneutic approach based on participants' "narrative plots"29. These results were organised according to proposed "structural pathogenic devices"30 and "systems of signs, meanings and practices"31. The explanatory model, as the result was called in accordance with a proposal by Kleinman32, was presented for validation both to the communities in which the in-depth study was conducted and to a group of traditional authorities.

ResultsBackground informationVaupés, in south-eastern Colombia, is one of the six departments in the country that comprise the South American Amazon macro-region. It has an area of 54,000 km2 and, according to the 2015 projection of the Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística [National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE)], a population of 43,665 inhabitants. Hence, it is one of the least densely populated departments in Colombia33. Of the population, 70% consider themselves to be indigenous and to belong to any of the 28 indigenous peoples primarily living in the sparse rural jungle area of the department. The remaining 30% consider themselves to be "mixed-race", "white" or "Afro-descendant" and mostly live in the urban areas of the three existing municipalities: Mitú, Carurú and Taraira.

The indigenous population is spread out across settlements known as "communities", which vary in size and organisation, and are characteristically located near the different rivers and pipes that cross the region. These communities follow certain rules and norms established long ago with roots in the Anaconda-Remedio origin myth34. According to this myth, an anaconda, composed of multiple anacondas, came from the east carrying the native people who, at different geographical landmarks with their respective history, came down from the anaconda and occupied a region.

The location of the native people in the Anaconda-Remedio origin myth symbolises a social hierarchy that is essential for understanding the social organisation of the region. This is rooted in the exogamous or language group in the area known as the "sociocultural complex of Vaupés" or the Cubeo and Arawak sib, with patrilineality and virilocality, which underlies family, social and friendship/enmity networks35.

Rules for day-to-day practices derive from a set of myths with variations among the 28 indigenous peoples. Most prominent among said myths is Yurupari, a story that demarcates central aspects of the peoples' world view, such as relationships to spaces and visible and invisible beings and male and female gender roles36,37. There are also stories of mythical heroes or "first men" from each of the indigenous peoples. These narrate essential teachings for survival, such as preparing tools, using fire, hunting, fishing and using plants. Finally, there are more family-centred stories, those pertaining to ancestry, which reproduce learnings acquired over centuries of observation with regard to optimum use of environmental resources. These three types of story undergo constant updating, which reflects the dynamics of the indigenous peoples' learning as well as their need to make sense of the changes to which they have been subjected38.

Behind each story and its discussion, as occurs in each family and at each settlement in day-to-day activities, is the configuration of a habitus (understood as ingrained structures determinant of dispositions in social settings39) that enables each of the peoples to survive. This is reaffirmed on an ongoing basis through not only acceptance and reproduction of that which the set of myths conveys, but also continuing engagement in rituals established for this purpose. The central role of the so-called traditional authorities is to ensure that this reaffirmation occurs40.

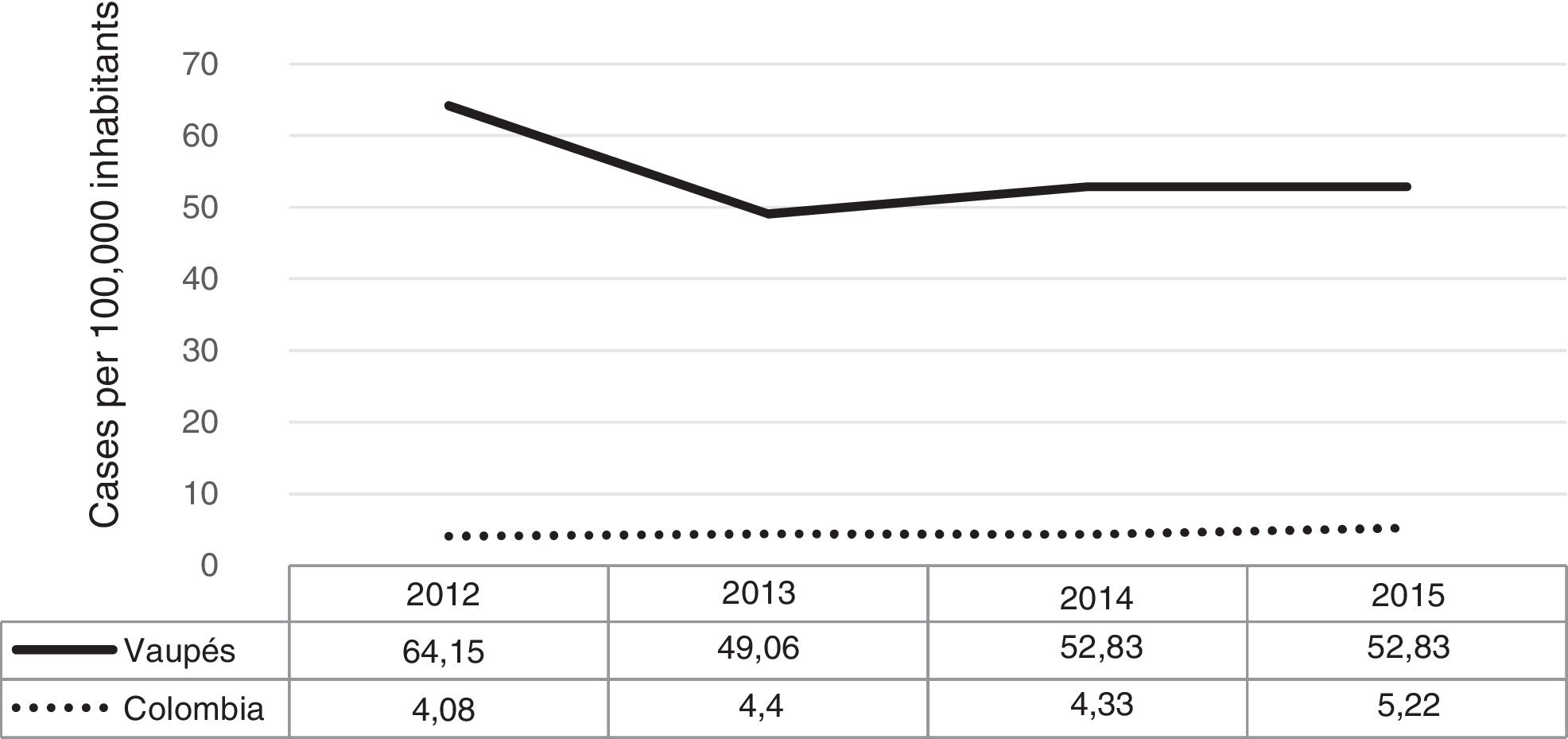

Deaths by suicide in Vaupés from 2012 to 2015For the period from 2012 to 2015, information could be gathered on 58 cases of deaths by suicide, grouped as follows: 17 cases in 2012, 13 cases in 2013, 14 cases in 2014 and 14 cases in 2015. This revealed a sustained trend with rates of 64.15, 49.06, 52.83 and 52.83 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively. Rates for the Department of Vaupés were compared to national rates and found to be 10–15 times higher than them in the period observed (Fig. 1).

Of the cases presented, one was "white", two were "mixed-race" and all the rest were indigenous. Strikingly, some deaths by suicide occurred in minority groups at risk of extinction, e.g. Siriano (5 cases), Jupdá (3 cases) and Carapana (3 cases). Some 63% of cases occurred in individuals under 25 years of age. The age group with the highest frequency was 15–19 years (23 cases).

Males accounted for 74% of cases. Of the 58 cases, 17 occurred in urban areas of municipalities; all others occurred in the rural areas of the department. Among the latter, it is conspicuous that a significant number of cases (22) occurred in peri-urban settlements easily accessed from municipal centres.

In 87% of cases the means of death by suicide was hanging, followed by poisoning and firearms.

Suicidal behaviour from an indigenous perspectiveInterviews with institutions made it clear that indigenous peoples are going through processes of profound acculturation/deculturation, some violent, expressed in not only biological but also sociocultural miscegenation. These processes are resulting in increased interest in residing in urban areas, regular consumption of distilled alcohol, use of non-ritual psychoactive substances or of ritual psychoactive substances outside this context, deterioration of family and kinship networks, and intra-family violence. These things are accompanied by more structural elements such as a scarcity of opportunities to develop other types of skill, reflected in unemployment rates. These things affect individual experiences with regard to affect, emotion and sexuality, often against a backdrop of "uprooting" due to the mobilisation of the population and the fragility of traditional support networks.

Payés, or shamans, the highest traditional authorities in the region, believe that suicidal behaviour is occurring as a result of a break with traditional norms, those stemming from the world view of the different peoples, causing the Dueños de las Cosas [Masters of Things], entities in charge of the visible and invisible elements of the jungle, to send an evil known as the "maldición" ["curse"] to the population. An alternative explanation is "maldad" ["wickedness"], a phenomenon that is sent by another payé or shaman (in this case, from Brazil) and has been moving through the different communities following kinship ties.

In the work with the population, the above emerged, formulated in various ways. Particular or "traditional" understandings that echoed the account of the payé or shaman were found. Matters associated with acculturation/deculturation were also indicated. For the population, acculturation/deculturation processes create vulnerability to the "curse" and "wickedness" as well as their effects. Finally, an understanding of a "material" nature, with needs, scarcity, lack of opportunities and difficulties in subsistence intersecting in the population's narrative, was also mentioned. All these elements place stress on traditional (family and kinship) support networks, which, as a result, are unable to respond adequately to critical events such as suicidal behaviours in community members.

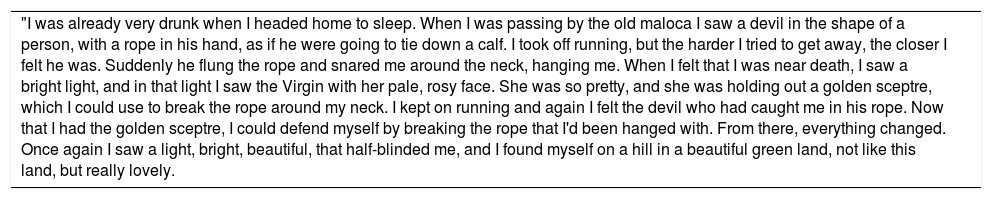

Verbal autopsies and interviews with survivors of suicidal behaviours suggested that suicide is preceded by behavioural changes. Reference was made to a number of "rebeldías" ["rebellions"], behaviours that break the rules and norms established in the set of myths that ensures the survival of the peoples, and to a loss of will to take part in family and group activities, which some linked to a loss of morale due to external "animosidad" ["animosity"] sending harm. Some narratives involve symbolism featuring an archetypical Judeo-Christian religious figure, often at odds with traditional beliefs; this may be accompanied by experiences of hallucination and persecution (Table 1).

Narrative of a survivor.

| "I was already very drunk when I headed home to sleep. When I was passing by the old maloca I saw a devil in the shape of a person, with a rope in his hand, as if he were going to tie down a calf. I took off running, but the harder I tried to get away, the closer I felt he was. Suddenly he flung the rope and snared me around the neck, hanging me. When I felt that I was near death, I saw a bright light, and in that light I saw the Virgin with her pale, rosy face. She was so pretty, and she was holding out a golden sceptre, which I could use to break the rope around my neck. I kept on running and again I felt the devil who had caught me in his rope. Now that I had the golden sceptre, I could defend myself by breaking the rope that I'd been hanged with. From there, everything changed. Once again I saw a light, bright, beautiful, that half-blinded me, and I found myself on a hill in a beautiful green land, not like this land, but really lovely. |

Social mapping revealed the presence and social recognition of various suicidal behaviours in each of the communities evaluated. Body mapping, by contrast, started to trace elements of affect, emotion and expectations of life that transcended the individual in favour of the group. The team is in the process of examining this in greater depth jointly with the population. Tensions around sexual orientation and possible forms of affective relationship emerged in a few interviews, representing another area of study.

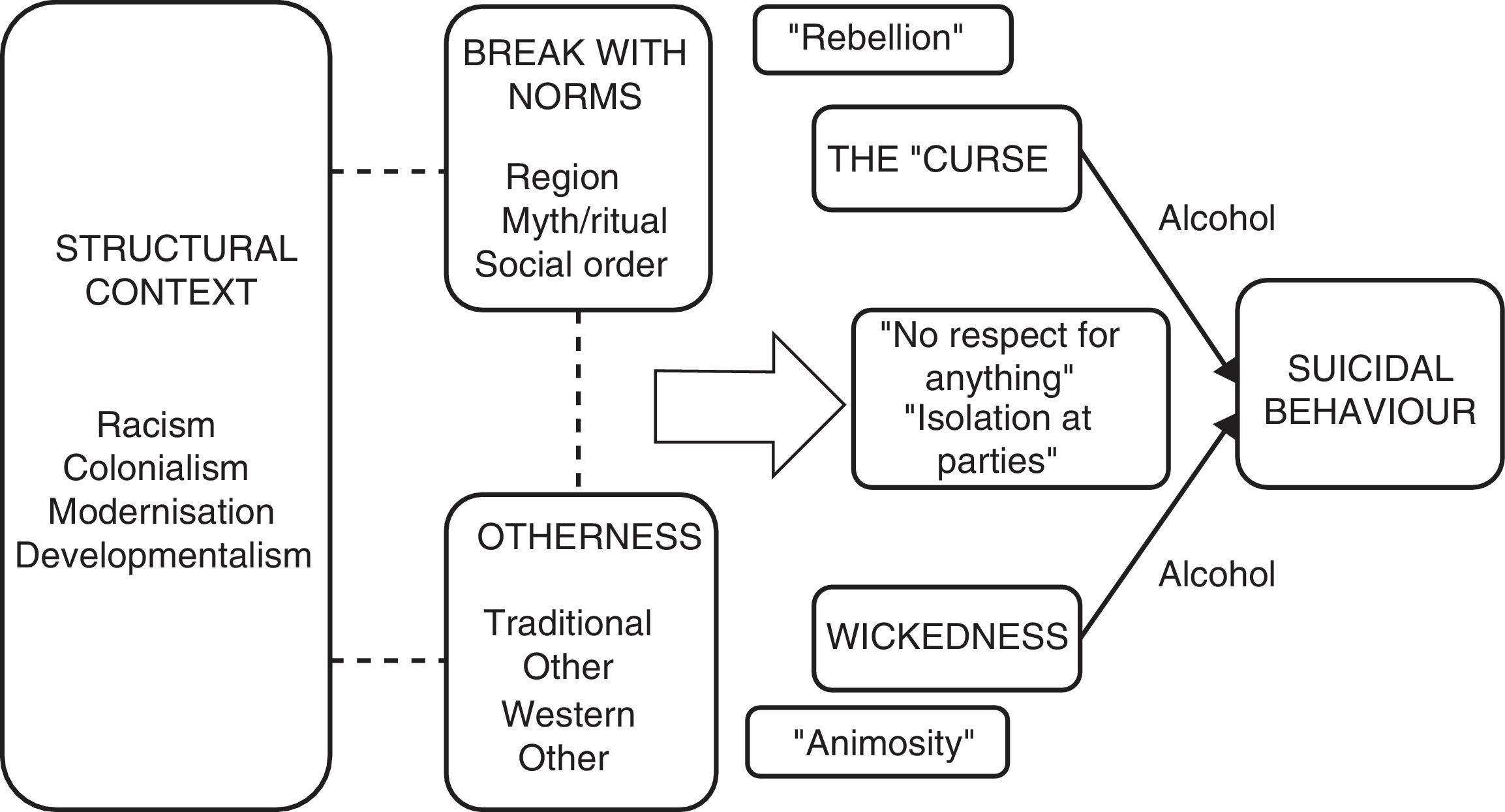

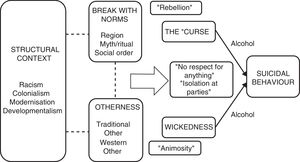

An explanatory modelThe above-mentioned elements offered a glimpse of an explanatory model, which was made into a graph to facilitate its comprehension (Fig. 2).

This may be read from either left to right or right to left, but we choose to read it from right to left in describing it. Suicidal behaviour appears on the far right, connecting "wickedness" and the "curse", the most common explanation for this behaviour. For this to happen, it is usually mediated by alcohol use, as well as publicly recognised behaviours.

Words such as "animosity" and "rebellion" describe behaviours related to "wickedness" and the "curse", respectively. The "curse", as a break with norms, characterises the disorder caused by the action of a single individual, and "rebellion" serves as a descriptor that encompasses regional, social, mythical and ritual aspects. "Animosity", on the other hand, reveals the desire of some Other to do intentional harm.

"Rebellion" does not come about naturally; rather, it occurs in a context of pressures and changes. These are mediated by structural elements such as racism, colonialism, developmentalism and all efforts to bring modernity to these indigenous peoples, resulting in elements of acculturation/deculturation recognised both by the population and by institutions. "Animosity" as a will of some Other finds a new application in this process. The Other is not limited to the Other of traditional explanations; the Western Other also brings these changes and creates a context of disorder in which rules break down.

DiscussionSuicidal behaviour is a high-priority problem in the indigenous population of the Department of Vaupés, as is evident from existing quantitative data. This behaviour particularly presents in young males from different indigenous peoples, especially those in the urban areas and periurban settlements in the department.

These data may be interpreted in light of the findings of the field study with the population and institutions. Young indigenous males are those who mostly find themselves in a structural context in which they are subject to constant acculturation/deculturation. This limits their identification with indigenous ways of being while simultaneously exposing them to structural violence that also limits their identification with foreign and Western ways of being. This situation which prevents said identification, Durkheim's anomie41, could be the main force driving suicidal behaviours in the region.

Anomie becomes embedded in bodies through a complex symbolic framework in the population's set of myths and enables sense-making of what are seen as behavioural changes, "rebellion" and "animosity", and the experiences narrated by survivors. This results in a fragmented habitus that limits the family and collective response to this situation, and, therefore, limits the recognition thereof as a problem that transcends the indigenous peoples themselves.

Many qualitative findings in indigenous peoples in the Department of Vaupés have been reported in other countries. Acculturation/deculturation deriving from racism, colonialism, developmentalism and modernisation has generally been associated with suicidal behaviours, although the mechanisms by which it affects different indigenous peoples vary from country to country42. In countries such as Canada and Australia, these things have been seen to be incorporated into collective symbolic frameworks and enable sense-making from a people's own perspective43,44.

In Latin America, the situation is similar. A recent systematic review highlighted the role of structural processes in what its authors called "cultural death"14, and what we term acculturation/deculturation herein. For the authors of that review, as for us, these processes give rise to stressors, which are associated with not only suicidal behaviour but also high consumption of alcohol, also a finding in our study. However, those authors did not enunciate other mediating elements such as those that emerged in the explanatory model.

In the case of Colombia, it is worthwhile to contrast the findings with those of other studies with the Emberá and Wounnán population in Córdoba and Chocó15,19,45,46. Diverging from our findings, those indigenous peoples have been found to present rates of suicidal behaviours higher among females though also concentrated in the same age groups as in Vaupés. In the Emberá and Wounnán peoples, jaibanás, or traditional authorities, like the rest of the population, recognise a number of behavioural changes preceding suicidal behaviour, called wawamia, or "madness"47. This suggests that these behaviours have been seen in the population for some time, unlike in Vaupés.

Wawamia includes changes in mood accompanied by experiences of hallucination and persecution similar to those described in Vaupés, and a particular type of seizure called a "jaí collapse"48. This name derives from the traditional explanation, where jaí represents the force that may be sent by another jaíbana or activated to damage the region. This bears obvious similarities to our explanatory model. A major difference is that, in addition to elements of acculturation/deculturation, the Emberá and Wounnán point to the important role of the armed conflict, which has arrived directly in their regions, as have development "mega-projects"49.

Although the anomic hypothesis has proven very useful in interventions, other hypotheses cannot be overlooked. In parallel with the community interventions carried out within the framework of the explanatory model, affective and emotional considerations in this population have been characterised and further vignettes explanatory of suicidal behaviours have been identified. In these vignettes, "romantic love", a Western notion associated with a break with traditional norms for searching for a partner in this context, is emerging with increasing force.

The explanatory model has guided a set of socioculturally appropriate interventions. It has steered efforts to manage alcohol use by individuals and groups; "community intelligence" has been developed which enables early identification of young people with behavioural changes seen in prior cases, and the use of traditional knowledge has been promoted to confront "wickedness" and the "curse" as symbolic vehicles for suicidal behaviours. An unfinished task deriving from this model is delimitation by institutions of socioculturally suitable interventions and intersectoral work to achieve structural changes.

ConclusionsAn explanatory model of suicidal behaviour yields a better understanding of the experience of indigenous peoples when this behaviour occurs. Its usefulness lies in the fact that it places interventions in context from a community and institutional perspective, thus facilitating intercultural dialogue between indigenous care and other care models.

In this case, early recognition of "wickedness" and the "curse" facilitates preventive community action against triggers. Working with traditional authorities and leaders on early warnings of this kind becomes an efficient strategy that requires dialogue to be opened up with institutions to create continuity.

An understanding of the processes underlying "wickedness" and the "curse" reveals that efforts to reinforce sociocultural rules such as rituals and actions by traditional agents are protective activities that enable prevention of suicidal behaviours. It also enables identification of individuals and groups, and therefore a more balanced relationship with the Western foreign Other.

Finally, recognising the profound structural inequalities and inequities that exist calls for taking action through sectoral and intersectoral public policy. Supporting processes by which indigenous peoples exercise their autonomy and own jurisdiction, such as the development of indigenous health and education systems, creates a forum for action heretofore not considered to address these phenomena.

The process undertaken shed light on two major challenges, which the team is currently exploring. The first is the need to better characterise the affective and emotional realities of the indigenous population. This involves recognising the processes of growth and development of the subjects that are occurring in these contexts. Advances in this regard will yield better tools for approaching this type of behaviour from a Western way of thinking.

The second is the recognition of specific aspects of traditional therapy, such as rituals, substance use in rituals and the role of the traditional agents in the region. All these things would open up new pathways towards understanding the "mental health" of indigenous peoples. They would also offer a glimpse of how psychotropic drugs could be introduced in this population and how alternative interventions could be introduced for the non-indigenous population.

These are both long-term processes. May this article serve to motivate other professionals in exploring transcultural mental health.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank the traditional authorities and indigenous population of the Suburbana Carretera and Río Abajo areas, where the fieldwork took place, as well as the community health agents Luis Hernando Rodríguez, Leonardo Rodríguez, Alfonso Martínez, Juan Manuel Rojas and Jorge Rodríguez. We would also like to thank the local directorates and institutions for health and social protection of the Department of Vaupés, with whom the ideas, knowledge and data presented here have been shared.

Please cite this article as: Silva PAM, Arenales MID, Prada AM, Van der Hammen MCR, Galvis yNM, Un modelo explicativo de la conducta suicida de los pueblos indígenas del departamento del Vaupés, Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:170–177.

This study was conducted as part of the project "Mejora de la salud y mayor protección contra enfermedades prioritarias para mujeres, niñas, niños, adolescentes y poblaciones excluidas en situaciones de vulnerabilidad en el departamento del Vaupés" ["Improved health and greater protection against priority diseases for women, boys, girls, adolescents and marginalised populations in vulnerable situations in the department of Vaupés"], funded by the Canadian International Development Agency, the Pan American Health Organization and the Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación [Colombian Presidential Agency of International Cooperation].

This study was presented at the 56th Colombian Psychiatry Conference, held from 26 to 29 October 2017 in Medellín, Colombia.