The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) need to be validated in non-European populations. The aims of this study were to determine how common NSSI was in a sample of self-harming Mexican adolescents and examine the associated variables.

MethodsWe examined the medical records of 585 adolescents with a history of self-injurious behaviour who attended a public hospital in Mexico City from 2005 to 2012. A group of experts established the diagnosis according to the DSM-5. The clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with and without NSSI were compared.

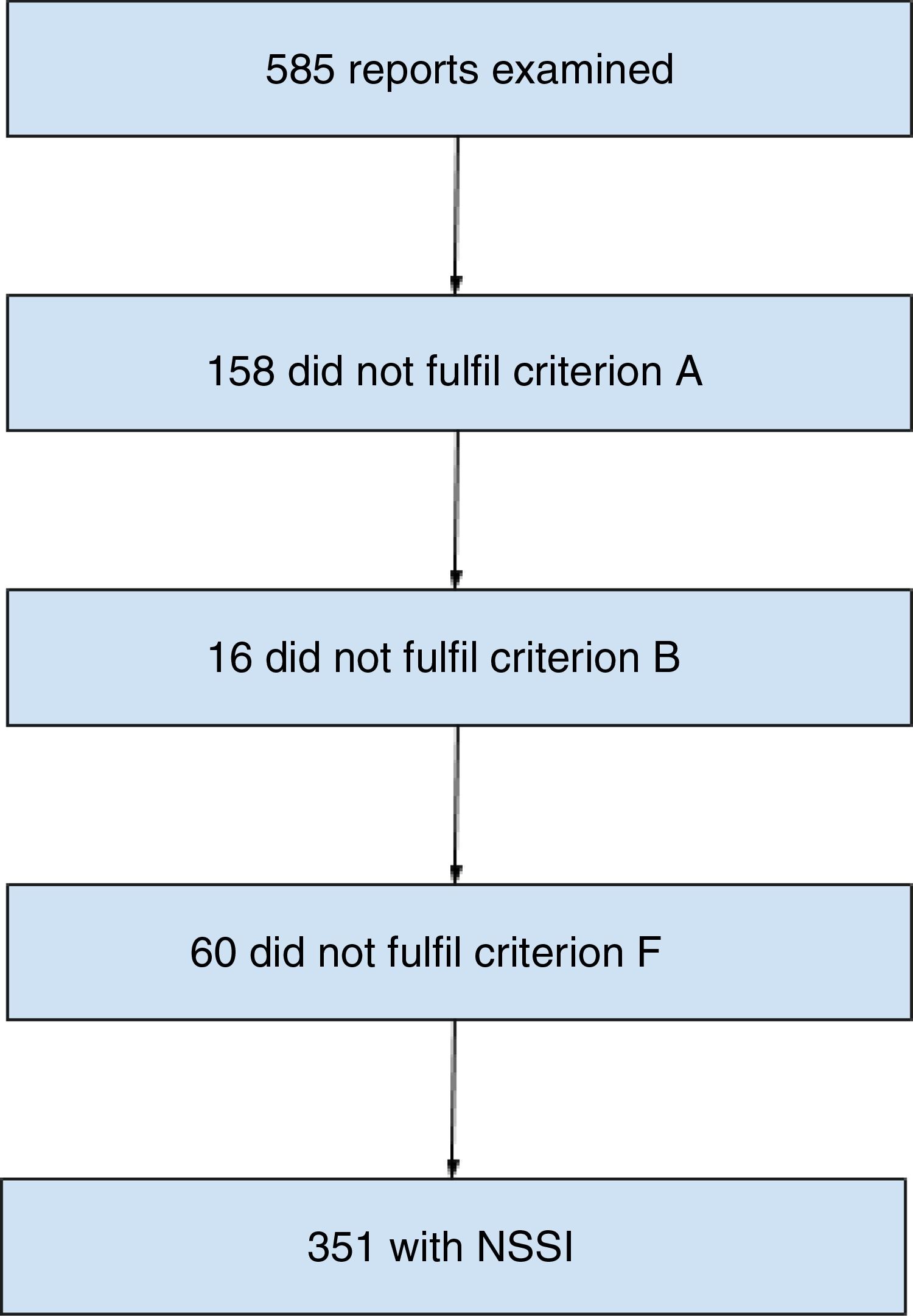

ResultsNSSI was diagnosed in 351 patients (60%) with evidence of self-harm. The main reasons for not being diagnosed were a previous suicide attempt (criterion A, 158 subjects [26.87%]) and another diagnosis that better explained the self-injurious behaviour (criterion F, 60 subjects [10.25%]). The NSSI group had a higher proportion of males (26.5% vs 16.2%) and patients with behavioural disorders (28.5% vs 13.7%). These patients were also found to seek psychiatric support in relation to their self-harm more frequently (31.9% vs 14.1%). The associated clinical characteristics included behavioural disorder (OR=2.51; 95% CI, 1.62–3.90), personality disorders (OR=0.56; 95% CI, 0.33–0.97), hospital admission (OR=0.23; 95% CI, 0.16–0.33), depressive symptoms (OR=0.60; 95% CI, 0.42–0.85), anxiety symptoms (OR=2.08; 95% CI, 1.31–3.31) and self-harming to influence others (OR=2.19; 95% CI, 1.54–3.11).

ConclusionsMore than half of the adolescents in the clinical sample with self-injury met DSM-5 criteria for NSSI. There are clinical and demographic characteristics which may be associated with this diagnosis.

El diagnóstico de lesiones autoinfligidas con fines no suicidas (NSSI) propuesto por el DSM-5 requiere estudios de validez en poblaciones diferentes de las europeas. Los objetivos del presente estudio son determinar la frecuencia de este diagnóstico en una muestra de adolescentes mexicanos con autolesiones y examinar las variables asociadas.

MétodosSe revisaron 585 expedientes clínicos de adolescentes con historia de autolesiones que acudieron a un hospital público en la Ciudad de México entre los años 2005 y 2012. Un grupo de expertos estableció el diagnóstico según el DSM-5. Se compararon las características clínicas y demográficas de los pacientes con y sin NSSI.

ResultadosSe diagnosticó NSSI en 351 pacientes con autolesiones (60%). Las razones principales de que no se diagnosticaran fueron haber realizado un intento suicida —criterio A, 158 sujetos (26,87%)— o que otro diagnóstico explicara las autolesiones —criterio F, 60 sujetos (10,25%)—. El grupo con NSSI incluyó una mayor proporción de varones (el 26,5 frente al 16.2%) y de pacientes con trastornos de conducta (el 28,5 frente al 13.7%); también se observó que estos pacientes solicitaban atención psiquiátrica debido a las autolesiones con mayor frecuencia (el 31,9 frente al 14.1%). Las características clínicas asociadas incluyeron trastorno de conducta (OR=2,51; IC95%, 1,62-3,90), trastorno de personalidad (OR=0,56; IC95%, 0,33-0,97), hospitalización (OR=0,23; IC95%, 0,16-0,33), síntomas depresivos (OR=0,60; IC95%, 0,42-0,85), síntomas de ansiedad (OR=2,08; IC95%, 1,31-3,31) y autolesionarse para influir en otros (OR=2,19; IC95%, 1,54-3,11).

ConclusionesMás de la mitad de los adolescentes con autolesiones de la población clínica cumplen los criterios diagnósticos de NSSI del DSM-5. Existen características clínicas y demográficas que pueden asociarse con este diagnóstico.

Self-harming behaviour is a phenomenon for which the prevalence in adolescents has been on the rise in different places in the world.1–4,6 Some studies on the demographic and clinical characteristics of self-harming patients have reported that this behaviour starts at an average age of 13 and is more common in females.2,4 The most common methods of self-harm are cuts, burns and interference in the healing of wounds on the limbs4 and, in more than half of cases, patients present symptoms of depression or anxiety as triggers of self-harm.1–4 The reasons for requesting psychiatric care for these patients include self-injurious behaviour per se, depression, anxiety and behavioural disturbances.3 Studies which have assessed the self-harming clinical population have shown that the most common disorders in self-harming subjects are anxiety disorders (64%) and major depressive disorder (60%).3 These studies have shown that a high percentage of these patients report suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts.1–4

During the drafting of the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), the creation of the diagnostic category of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) was proposed,5 given its high frequency and its association with suicidal behaviour.6–9 Although this diagnosis had criterion validity, given that expert clinicians and researchers considered that the criteria included in the DSM-5 reflect the clinical picture observed in their patients,10 the field studies showed very low temporal reliability (κ<0.20),11 which is why the diagnosis was included in the category of conditions which require further study.

The discussion regarding whether NSSI should be a diagnostic category is not recent. Cases of self-harm have been reported since antiquity and self-harm has been treated as part of mental illnesses since the 19th century, when they were integrated into diagnoses such as psychosis, masochism and borderline personality disorder, leading to the suggestion of considering a diagnostic category for DSM-IV. Although the concepts of self-harm have been subject to what has been considered a socially acceptable behaviour in each period,12 there is currently a growing prevalence of this behaviour, a clear association with psychopathology and with the increase in suicide risk.6 Therefore, the most rational behaviour, as Zetterqvist states,13 is to carry out research to determine whether the criteria of this diagnosis are fulfilled in different clinical populations.

In recent years, several studies have been carried out to determine the validity of the diagnosis by examining the frequency with which a self-harming clinical or open population fulfils each one of the proposed criteria using scales and/or structured interviews. In almost all of them, their utility14,15 is confirmed, although that of criterion B has been questioned, as all subjects self-harm to change their emotions or to resolve an interpersonal conflict.16 In these studies, it was observed that criterion E, which refers to the alterations of functioning due to self-harm, is fulfilled less often,17,18 although this is a criterion which is scarcely examined.19

The study of NSSI has raised two issues: the first relates to suicidal behaviour, as some subjects self-harm knowing that they are not inflicting serious bodily injury, but at the same time they have suicidal thoughts.18,20 The second problem is that, in most cases, subjects receive other diagnoses, mainly depression and anxiety, which could indicate that NSSI are more a severity specifier than a diagnostic category.

In addition to this, studies on NSSI have been carried out mainly in European countries and in the United States, and the information on the frequency with which several diagnostic criteria are fulfilled in adolescents from Latin American countries is limited. In view of this, the objectives of this study were to determine the frequency of NSSI among self-harming Mexican adolescents and to compare within a hospital setting the demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who fulfil the criteria and those who do not.

MethodsThe study was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee; its design was retrospective, observational and descriptive based on the review of records21 of the Hospital Psiquiátrico Infantil Dr. Juan N. Navarro (Dr. Juan N. Navarro Children's Psychiatric Hospital), which is a tertiary centre located in Mexico City, in which patients up to the age of 18 with mental disorders and neurodevelopmental disorders from all over the country are treated in the inpatient and outpatient clinic departments.

The sample selected consisted of adolescents aged 12–17 who attended assessment in the period between 2005 and 2012 and had self-harmed on at least five occasions during the past year.

To establish the diagnosis of NSSI according to the DSM-5, a panel of three clinicians with at least four years of experience reviewed each record and established by consensus if the patient met each one of the six criteria (A–F). In the borderline cases, two experts with at least 10 years of experience determined whether the patient met the NSSI diagnostic criteria. For the diagnosis, it was decided to group the B and C criteria, which talk about the expectations of the individual when self-harming and his/her reasons for doing so, coding the reasons for self-harming, as it was difficult to determine through the review of the records if there was a period of concern prior to the self-harming act or if the patient frequently thought about self-harming. It was not possible to determine whether criterion E was fulfilled (significant interference with functioning) due to the fact that the record did not establish whether the psychosocial dysfunction of the patients was associated exclusively with the self-harming. Other variables that were recorded for analysis were age, gender, education, comorbid diagnoses, history of suicide attempts, frequency and reasons for self-harming.

Statistical analysisIt was carried out with the SPSS program version 18.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences; Chicago, United States). Descriptive statistics were used for the demographic and clinical and comparative statistics variables (Pearson's χ2 test for frequencies and Student's t-test for means) to evaluate the differences between patients with and without the diagnosis. The odds ratio [OR] were reported without adjusting to its 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) to indicate the risks from bivariate relationships. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05.

ResultsA total of 9,673 records were reviewed and a sample of 585 self-harming adolescents was obtained, the mean age was 14.4±1.5 years and 77.6% (n=454) were females. It was found that 60% (n=351) fulfilled the NSSI criteria of the DSM-5. The 234 remaining patients were classified as without NSSI despite having had more than five incidences of self-harming in a one-year period (Fig. 1).

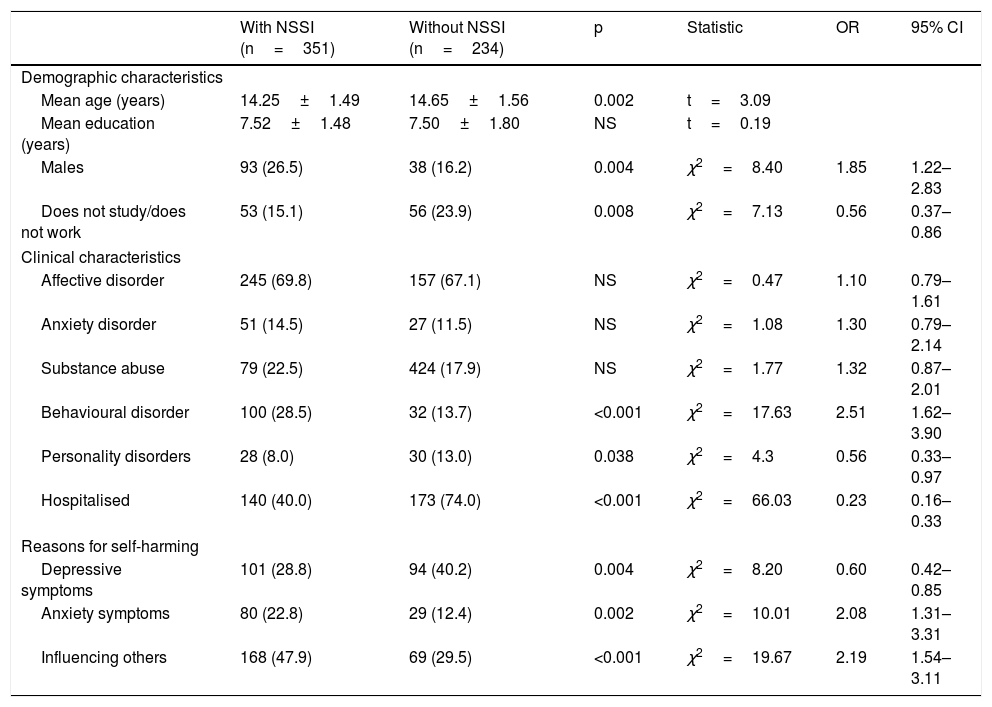

Table 1 shows the significant differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics and the reasons for self-harming between both groups. Patients in the NSSI group reported self-harming as a reason for consultation more frequently (31.9 versus 14.1%; OR=2.85; 95% CI, 1.85–4.39; p<0.001).

Significant differences between patients with and without the diagnosis according to the DSM-5.

| With NSSI (n=351) | Without NSSI (n=234) | p | Statistic | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Mean age (years) | 14.25±1.49 | 14.65±1.56 | 0.002 | t=3.09 | ||

| Mean education (years) | 7.52±1.48 | 7.50±1.80 | NS | t=0.19 | ||

| Males | 93 (26.5) | 38 (16.2) | 0.004 | χ2=8.40 | 1.85 | 1.22–2.83 |

| Does not study/does not work | 53 (15.1) | 56 (23.9) | 0.008 | χ2=7.13 | 0.56 | 0.37–0.86 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Affective disorder | 245 (69.8) | 157 (67.1) | NS | χ2=0.47 | 1.10 | 0.79–1.61 |

| Anxiety disorder | 51 (14.5) | 27 (11.5) | NS | χ2=1.08 | 1.30 | 0.79–2.14 |

| Substance abuse | 79 (22.5) | 424 (17.9) | NS | χ2=1.77 | 1.32 | 0.87–2.01 |

| Behavioural disorder | 100 (28.5) | 32 (13.7) | <0.001 | χ2=17.63 | 2.51 | 1.62–3.90 |

| Personality disorders | 28 (8.0) | 30 (13.0) | 0.038 | χ2=4.3 | 0.56 | 0.33–0.97 |

| Hospitalised | 140 (40.0) | 173 (74.0) | <0.001 | χ2=66.03 | 0.23 | 0.16–0.33 |

| Reasons for self-harming | ||||||

| Depressive symptoms | 101 (28.8) | 94 (40.2) | 0.004 | χ2=8.20 | 0.60 | 0.42–0.85 |

| Anxiety symptoms | 80 (22.8) | 29 (12.4) | 0.002 | χ2=10.01 | 2.08 | 1.31–3.31 |

| Influencing others | 168 (47.9) | 69 (29.5) | <0.001 | χ2=19.67 | 2.19 | 1.54–3.11 |

The results of this study show that 60% of self-harming adolescent patients fulfil the NSSI criteria of the DSM-5. When comparing these findings with those reported in other clinical population studies, a higher prevalence of diagnosis is found, probably due to the fact that this study included the inpatient and outpatient population, in contrast with the samples made up only of hospitalised patients.15 However, other studies with samples obtained in specialist clinics for self-harming patients or with borderline personality disorder have reported a higher prevalence of this diagnosis.14,22

With regard to the percentage of subjects who did not fulfil the criteria proposed, it was observed that in most of the records of subjects classified as without NSSI, suicidal thoughts or suicide attempts were documented. They therefore did not fulfil criterion A. It is important to take into account that, as it was a review of records, it was not possible to determine if the subjects had suicidal thoughts while they were self-harming: this concomitance has been highlighted in previous studies2,15,23 and it has been shown that suicidal thoughts are alternated with self-harm,6 which puts into question the temporal stability of NSSI and contributes to its characterisation as a risk factor of suicide attempt after one year. The comparison between groups showed a higher proportion of males and subjects diagnosed with behavioural disorders in the group of patients with NSSI, findings that contrast with what was reported in previous studies in an open adult population24 and clinical population of adolescents and young adults,14 in whom no significant differences due to gender were found. Although this may be due to age and the type of population studied, it indicates the need to carry out more studies on demographic differences between patients with and without the diagnosis of NSSI.13

Ougrin,25 by comparing self-harming adolescents with and without suicidal behaviour, found that the behavioural disorder presented more frequently in those who self-harmed but did not manifest suicidal behaviour, a finding similar to that of this study. Self-harming subjects have shown high prevalence of aggression, externalising disorders, substance use and alcohol addiction,26 which makes it necessary to evaluate self-harm in patients of both genders and with disorders other than depression and anxiety which have traditionally been associated with this phenomenon. A frequent reason for hospitalisation is suicide attempts, which is why we believe that the lowest proportion of hospitalised patients in the NSSI group may be explained by the exclusion of this diagnosis in these subjects.

The results show that the reasons for self-harming which distinguish the group with NSSI are depressive and anxiety symptoms and the act of influencing others; this finding coincides with what is published, which shows that the act of self-harming is carried out in response to anxiety or affective symptoms2 and that the self-harming behaviour of adolescents often leads to changes in their social and family relationships.27

Although it was not possible to signal self-harming as the only cause of dysfunction in patients, most of the subjects of the group with NSSI requested psychiatric consultations due to self-harming. It could therefore be inferred that these patients fulfil criterion E.

The main limitation of this study is that the information was obtained from a review of records, which implies that the diagnostic process of the patients was heterogeneous and, in some cases, the information could not be completed. However, it was sufficient to establish that more than half of the self-harming subjects fulfilled the NSSI diagnostic criteria proposed in the DSM-5.5 It is important to carry out more studies on this diagnosis in Latin American adolescents. Future research on the topic in patients of Hispanic origin should probably elaborate on the characteristics that the suicidal behaviour of patients with NSSI may predict, in addition to examining the diagnostic stability of these patients through longitudinal studies and their behaviour as a severity specifier.

ConclusionsThis study provides information on the validity of this category in populations of Hispanic origin, as it reveals that more than half of the self-harming subjects could fulfil the diagnostic criteria established in the DSM-5 and shows the clinical characteristics that could be associated with this diagnosis in Mexican adolescents.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

To Doctors Cecilia Contreras and Karina Paniagua for their support in the management of the data.

Please cite this article as: Flores REU, et al. Lesiones autoinfligidas con fines no suicidas según el DSM-5 en una muestra clínica de adolescentes mexicanos con autolesiones. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:39–43.