The recommendations of the current guidelines are based on low quality evidence. Periodic updating is required, taking recent evidence into consideration.

ObjectiveTo synthesise the best available clinical evidence on the efficacy and safety of second-generation antidepressants and antipsychotics in patients with anorexia nervosa.

MethodsSystematic review (CRD42020150577). We searched PubMed, SCOPUS, Ovid(Cochrane), EMBASE and LILACS for randomised clinical trials performed in patients with anorexia nervosa that evaluated the use of second-generation antipsychotics or oral antidepressants, at any dose and for any length of time, in outpatient and/or hospital treatment, taking weight (body mass index), psychopathological entities and safety as results.

ResultsFive studies were included, with four assessed as having a high risk of bias. The evidence indicates that patients receiving treatment with olanzapine or fluoxetine tend to stay in treatment programmes for longer. Olanzapine showed favourable results (one study) in terms of weight gain, but did not show the same results in psychopathology, where the evidence is contradictory.

ConclusionsIn accordance with previous reviews, our work allows us to conclude that there is contradictory information on the efficacy of psychotropic drugs in the treatment of anorexia nervosa. Future work should focus on developing clinical trials of high methodological quality.

Las recomendaciones de las guías vigentes están basadas en evidencia de baja calidad. Se requiere su actualización periódica considerando la evidencia reciente.

ObjetivoSintetizar la mejor evidencia clínica disponible sobre eficacia y seguridad de antidepresivos y antipsicóticos de segunda generación en pacientes con anorexia nerviosa.

MétodosRevisión sistemática (CRD42020150577). Se buscaron en PubMed, SCOPUS, Ovid (Cochrane), EMBASE y LILACS los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados realizados en pacientes con anorexia nerviosa que evaluasen el uso de antipsicóticos de segunda generación o antidepresivos orales a cualquier dosis y por cualquier tiempo en el tratamiento ambulatorio y/u hospitalario tomando como resultados el peso (índice de masa corporal), las entidades psicopatológicas y la seguridad.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 5 estudios, 4 catalogados como con alto riesgo de sesgo. La evidencia indica que los pacientes que reciben tratamiento con olanzapina o fluoxetina tienden a mantenerse por más tiempo dentro de los programas de tratamiento. La olanzapina mostró resultados favorables (un estudio) en cuanto al aumento de peso, pero no mostró los mismos resultados en psicopatología, donde la evidencia es contradictoria.

ConclusionesEn concordancia con las revisiones anteriores, nuestro trabajo permite concluir que hay información contradictoria sobre la eficacia de los psicofármacos para la anorexia nerviosa. El trabajo futuro debe enfocarse en desarrollar ensayos clínicos de alta calidad metodológica.

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is defined as abnormal eating behaviour characterised by excessive weight loss, which is started or maintained voluntarily, accompanied by a distorted body image.1,2 AN has a prevalence of up to 4% in young women3; typically, it starts around 18 years of age and tends to become chronic and associated with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus,4 bipolar affective disorder, major depressive disorder and anxiety disorders.1

These conditions in a patient with AN are difficult to treat, with rates of treatment failure around 35–79% in patients who have received some sort of medical treatment.4 The high rate of treatment failure entails demand for hospitalisation services, treatment for complications, polypharmacy and disabilities, resulting in high costs for health systems for the care of these patients.5–7 Relapse rates after treatment are very high, and AN is the deadliest of all psychiatric diseases.8

At present, the cornerstone of AN treatment is psychotherapy, alternatives such as cognitive behavioural therapy, the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults (MANTRA) and Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM) are recommended as equivalents; however, the evidence backing this recommendation is of low quality.9,10 Regarding pharmacological management, recommendations based on low-quality evidence are given in favour of low-dose antipsychotics, especially olanzapine, with moderate usefulness for weight gain, treatment of symptoms of anxiety and obsessive thoughts.7

Regarding mechanisms of action, serotonin neurotransmission through the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus is known to produce signals of satiety and inhibit eating; therefore, serotonin neurotransmission appears to be important in AN aetiology and drug treatment.11–13 Serotonin is also involved in other types of behavioural dysregulation such as depression, anxiety and psychosis, which often occur in patients with AN.8,14,15

Therefore, it is indicated that medicines with a predominantly serotonergic mechanism of action may have some therapeutic effects in patients with AN.16

With regard to the use of antidepressants, however, the evidence is contradictory. The German guidelines advise against using serotonin reuptake inhibitors,9 while the guidelines of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry and the American Psychiatric Association17 recommend them with caution.

The fact that current guidelines are based on low-quality evidence renders it a priority to regularly update processes of evidence synthesis, including the latest clinical studies, such that the recommendations can be updated and re-evaluated with a view to decreasing uncertainty associated with methodological quality and strength of recommendation.

Thus, the objective of this study was to synthesise the best clinical evidence available on the efficacy and safety of antidepressants and second-generation antipsychotics in patients with AN, with efficacy measured by weight gain using body mass index (BMI).

MethodsProtocol and registryThe review protocol was developed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions18 and was registered in the PROSPERO repository (code: CRD42020150577). This article follows the suggestions for reporting of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.19

Study eligibility criteria and information sourcesStudies on the following were considered eligible: (P) patients over 14 years of age with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa according to DSM-IV and DSM-V criteria (I); use of second-generation antipsychotics or oral antidepressants at any dose and for any duration in outpatient and/or inpatient treatment, alone or in combination with other pharmacological or non-pharmacological treatments; on (C) conventional treatment, placebo or a waiting list; and, in those in whom they were assessed, using valid psychometric scales or a clinical interview (O), changes in weight measured by BMI, in addition to psychopathological entities, such as affective, anxious or obsessive symptoms. Only (S) randomised clinical trials with follow-up for (T) at least four weeks were included. Articles in English, Spanish or Italian published up to the date of the last search (18 September 2019) in PubMed, Scopus, Ovid (Cochrane), Embase or LILACS were considered. As additional sources, the references for the studies included were verified, and clinicaltrials.gov was searched for studies in progress.

Search strategy and study selectionThe search strategy used in PubMed was: "anorexia[Title/Abstract] AND (aripiprazole[Title/Abstract] OR haloperidol[Title/Abstract] OR olanzapine[Title/Abstract] OR amitriptyline[Title/Abstract] OR bupropion[Title/Abstract] OR citalopram[Title/Abstract] OR clomipramine[Title/Abstract] OR desvenlafaxine[Title/Abstract] OR duloxetine[Title/Abstract] OR escitalopram[Title/Abstract] OR fluoxetine[Title/Abstract] OR fluvoxamine[Title/Abstract] OR imipramine[Title/Abstract] OR mirtazapine[Title/Abstract] OR paroxetine[Title/Abstract] OR quetiapine[Title/Abstract] OR risperidone[Title/Abstract] OR sertraline[Title/Abstract] OR venlafaxine[Title/Abstract]) AND (random*[Title/Abstract] OR efficac*[Title/Abstract])".

The same strategy was used to search the remaining sources of information with changes in the corresponding syntax only.

All study records identified were stored in an Excel workbook from which duplicates were removed. Five investigators (ASL, JMS, CVM, MCM and FVE) sifted through the titles and abstracts and excluded those not pertinent to the PICO question; in cases in which pertinence could not be determined in this way, the article was retained for full-text review. The same investigators reviewed the full text of the eligible articles and excluded those that were not pertinent to the PICO question or did not match the study type criteria. A consensus on the studies included in the narrative review was reached among all the investigators.

PICO variables and data extraction processThe full text of each article included was read independently by two investigators and the information extracted was recorded in an Excel workbook; discrepancies were resolved by reviewing the original document as a whole. The characteristics extracted were: (P) distribution by age and sex, clinical characteristics, and geographic or institutional context; (I, C) treatment for the experimental group and for the control group, concomitant interventions, operator characteristics, and sample size; (O) attributes, measuring instrument, operator characteristics and values at baseline and at the end of the study; (T) follow-up time; and (S) surname of the first author, year of publication, year of execution and type of study. The characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies included.

| Study | Sample | Mean age (years) | Intervention | Comparator | Duration | Outcomes | Losses | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walsh 2006 | 93 | 22.4 (fluoxetine group), 24.2 (placebo group) | Fluoxetine+CBT | Placebo+CBT | 12 months | Time to relapse, measured by BMI | 0 | Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health. Eli Lilly provided fluoxetine and placebo |

| Bissada 2008 | 34 | 23.6 (olanzapine group), 29.6 (placebo group) | Olanzapine | Placebo | 10 weeks | Rate of weight gain, measured by BMI | 12 | Supported by a grant from Eli Lilly |

| Mondraty 2005 | 26 | 25.3 (olanzapine and chlorpromazine group) | Olanzapine | Chlorpromazine | 12 months | Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) and the Padua Inventory | 0 | Not reported |

| Kaye 2001 | 35 | 23 (fluoxetine group), 22 (placebo group) | Fluoxetine | Placebo | 12 months | Time to relapse, measured by BMI | 22 | Eli Lilly Corporation and the National Institute of Mental Health |

| Attia 2019 | 152 | 28 (olanzapine group), 30 (placebo group) | Olanzapine | Placebo | 16 weeks | Rate of change in body weight and rate of change in obsessiveness | 69 | Supported by the National Institutes of Health. Eli Lilly provided olanzapine and combination placebo pills, but did not provide financial support |

BMI: body mass index; CBT: cognitive behavioural therapy.

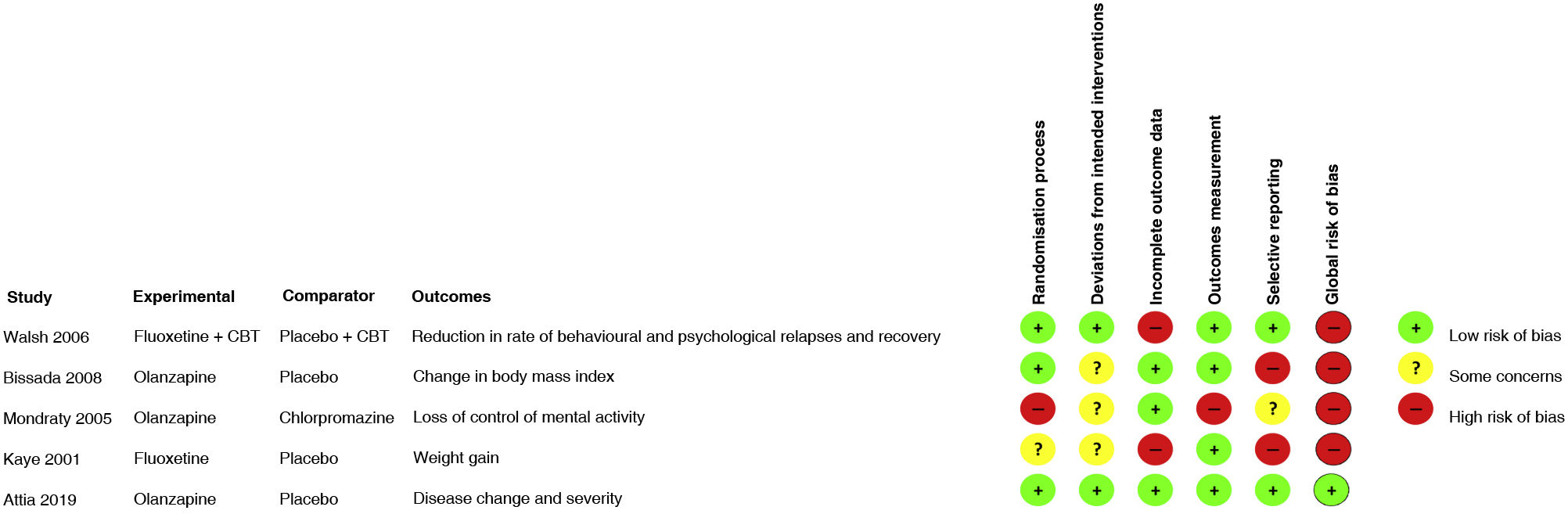

For each study included, two investigators conducted the assessment of risk of bias on an individual study level; differences were resolved by consensus among all investigators. The instrument used was Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0), taking into account its five dimensions: randomisation process, deviations from intended interventions, incomplete outcome data, measurement of outcomes and selecting reporting of results; an assessment of global risk of bias of the study was conducted.20 The assessment was performed by consensus among all four investigators based on the recommendation of the instrument. Studies considered to be at high risk of bias were excluded from the evidence synthesis. The table presents the assessment of each study in terms of each item and a summary figure of the risk of bias of all the studies included.

Summary measures and synthesis of resultsFor each outcome, the mean difference between intervention groups was taken along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). As per protocol, no meta-analysis was performed due to differences between studies in terms of methodological characteristics.

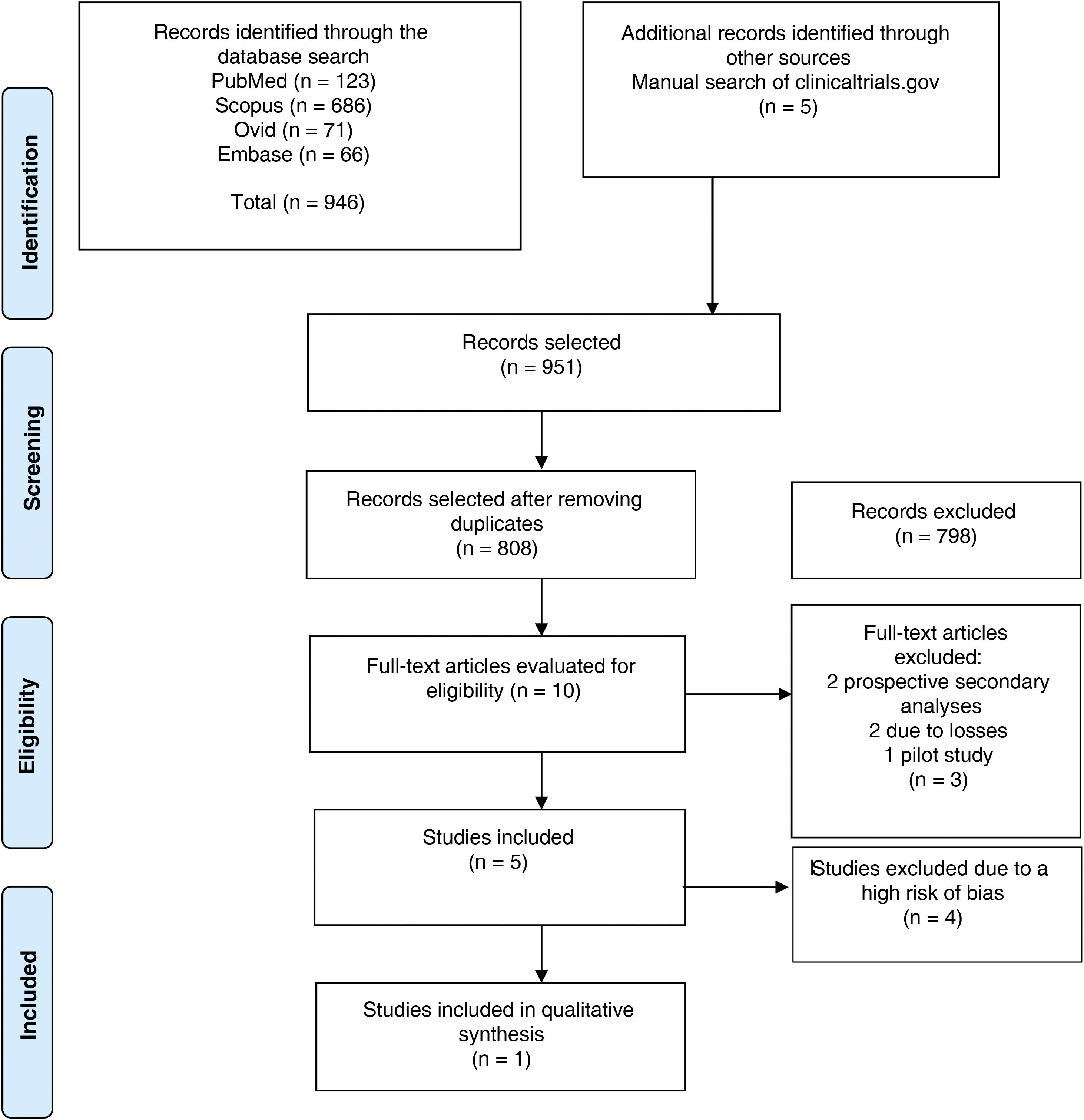

ResultsSearch resultsFig. 1 features the study selection flow chart. After duplicates were removed, 808 references were identified. Through reading of titles and abstracts, 798 were ruled out. The full text of the remaining 10 was reviewed and five were excluded: two as they were secondary analyses, two due to the magnitude of their losses to follow-up and one as it was a pilot study. A total of five randomised clinical trials were included in data extraction and assessment of risk of bias.

PRISMA flow chart. From Moher et al.19

Of the five studies included, two compared olanzapine to placebo, two compared fluoxetine to placebo and one compared olanzapine to chlorpromazine. With a total of 340 participants with AN, sample sizes ranged from 26 to 152 participants and study duration ranged from six to 52 weeks. In all the clinical trials, women accounted for more than 95% of the participants. Table 1 shows a summary of the main characteristics of each study.

A study by Walsh21 had a sample of 93 patients, who received intensive inpatient treatment or treatment in the day hospital programme of the New York State Psychiatric Institute or Toronto General Hospital. They were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine or placebo. Randomisation lists, stratified by site and subtype of compulsive purging, were generated by a computer program using a random number generator. The dose of medication was maintained at 60mg/day unless there were adverse effects, in which case the dose was reduced at the discretion of the psychiatrist. They were treated for 12 months, until they met the criteria for early withdrawal from the study or until they withdrew voluntarily. Evaluations were collected every four weeks using the Eating Disorder Inventory, the Beck Depression Inventory, the Beck Anxiety Inventory and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

A study by Bissada22 had a sample of 34 patients with a diagnosis of AN randomly assigned to treatment with olanzapine plus treatment at a day hospital or placebo plus treatment at a day hospital; randomisation was stratified by AN subtype (restriction or binge/purge). Olanzapine was prescribed according to a flexible-dose regimen, starting with the minimum dose of 2.5mg/day and slowly titrated in increments of 2.5mg/week up to a maximum dose of 10mg/day. The study duration was 13 weeks. Hierarchical linear modelling was used to model the trajectories of changes in the growth curve for each patient's BMI.

A study by Mondraty23 had a sample of 26 patients, 15 of whom were randomly assigned in a balanced block design: eight to olanzapine and seven to chlorpromazine (controls). An investigator outside the study carried out the randomisation process. A sequence of random numbers was generated by flipping a coin. Both medicines were started at a low dose and increased until a satisfactory effect was achieved, a maximum dose was reached or a side effect was seen. The Eating Disorder Inventory-2 (EDI-2) and the Padua Inventory were applied as part of the evaluation. The study duration was 12 months.

A study by Kaye24 had a sample of 35 patients with restricting AN randomised to fluoxetine (n=16) or placebo (n=19) after weight gain in hospitalised patients who were then observed on an outpatient basis for one year.

A study by Attia25 featured a sample of 152 outpatients with AN and was conducted at five sites in North America. The participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive olanzapine or placebo and were seen weekly for 16 weeks. The primary endpoints were the rate of change in body weight and the change in obsessive compulsive symptoms related to food and the body were measured using the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale for Eating Disorders (Y-BOCS-ED).

Risk of biasFour of the five studies included in the review were classified according to the RoB 2.0 as at high risk of bias (Fig. 2). There were deficiencies in the randomisation process domain in Kaye's study,24 since there was no clear description of this process. In Mondraty's study,23 there were deviations from the planned measurements, since the data were not analysed in accordance with a plan specified before the results were available. In the studies by Mondraty, Kaye and Bissada,22 there were inconsistencies, since an appropriate analysis to estimate the effect of the intervention was not used and not all patients and auditors were blinded. Furthermore, the clinical trials conducted by Bissada and Kaye used multiple measurements and analyses for a single result, thus increasing the possibility of biased results. Finally, with respect to missing outcome data, high risk was found in the studies by Kaye and Walsh;21 in the former, just 63% of the patients in the intervention group and 16% of the patients in the placebo group completed follow-up, and in the latter, just 43% completed follow-up.

Results of individual studiesKaye's clinical trial compared effects on relapse prevention in fluoxetine versus placebo in outpatients with AN. Sixty-three per cent of the patients from the fluoxetine group and 16% from the placebo group completed one year of follow-up, with a trend towards completing the study in the intervention group. The authors compared four groups (fluoxetine versus placebo and those who completed follow-up versus those who did not). In the end, all four groups showed a significant interaction for the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score and a trend for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS). This analysis showed no differences in weight, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) score or score for eating disorder-related obsessions and compulsions. Using the t test for paired data, the group that remained on fluoxetine for one year showed a significant difference in terms of weight gain and reductions in anxiety, depression, obsessions, compulsions and cardinal symptoms of an eating disorder.

Another clinical trial21 compared fluoxetine to placebo. Forty-nine patients were assigned to fluoxetine and 44 were assigned to placebo. Of the 93 patients, 40 completed the full course of treatment and 53 stopped early. Analysis of time to relapse, in which premature suspension for any reason was considered to mean a relapse, found no significant differences between the fluoxetine and placebo groups (r=−0.133; SE=0.288; df=1; p=0.64).

Three clinical trials evaluated the use of olanzapine. Mondraty's study compared olanzapine to chlorpromazine. It had eight participants in the olanzapine arm and seven in the control arm. Average weight gain across all patients was 5.5kg, with no significant differences between the two groups. The study found a reduction in rumination, which was significantly greater in the olanzapine group than in the control group (54% versus 9%). The decrease in severity of cognitive symptoms was clinically significant on all subscales (EDI-2) for olanzapine.

Another clinical trial22 evaluated the effects of olanzapine on weight gain in patients with AN, with an average dose of 6.61mg/day for 10 weeks. All patients had significant weight gain per their BMI (β10=0.29; t=7.44, df=32; p<0.001); the olanzapine group had higher rates of increased BMI than the placebo group (β11 = −0.06; t = −2.25; df=31; p=0.03). In the survival analysis, 55.6% of patients on placebo and 87.5% of patients on olanzapine achieved weight restoration; average survival was 8±0.68 (95% CI, 6.74–9.39) weeks with olanzapine and 10±0.67 (95% CI, 8.75–11.36) with placebo.

In a multicentre study,25 152 outpatients were assigned to receive medication or placebo (75 in the olanzapine group and 77 in the placebo group). Olanzapine was associated with a significantly higher rate of weight gain (monthly increase in BMI 0.259±0.051) than placebo (monthly increase in BMI 0.095±0.053; F=4.98, df=1.1435; p=0.026). There was no evidence of olanzapine having a significant impact on psychiatric disease in AN, such as obsessions or excessive preoccupation with weight gain.

Safety and tolerabilityFour of the five studies included featured descriptions of safety and tolerability. In relation to chlorpromazine, there were three reports of adverse effects — one of sedation, one of blurred vision and one of orthostatic hypotension — but they were linked to higher antipsychotic doses.

Two of the three studies that evaluated olanzapine found no significant adverse effects, but Attia's study did report effects described as moderate to severe linked to olanzapine, including difficulty concentrating (14.5% versus 32.7%; χ2=5.45; p=0.02), difficulty staying still (6.5% versus 18.2%; χ2=3.81; p=0.05), trouble sleeping (9.7% versus 30.9%; χ2=8.32; p=0.004) and trouble staying asleep (14.5% versus 40.0%; χ2=9.72; p=0.002).

A 17-year-old patient assigned to fluoxetine made a suicide attempt during the study but, given the small sample size and the low rates of completion of the two fluoxetine trials, we were unable to determine whether this suicide attempt in an underweight adolescent on treatment with fluoxetine differed in some way from treatment in normal-weight individuals with other psychiatric diagnoses.

In general, rates of suspension attributed to adverse events did not significantly differ between individual medicines.

DiscussionThis systematic review sought to identify the efficacy of antipsychotics and antidepressants in the treatment of AN by updating the evidence based on studies conducted in the past 19 years. In summary, the evidence is insufficient to recommend psychiatric drugs for the treatment of anorexia.

Among the studies included, we found that patients who received treatment with any psychiatric drug, be it olanzapine or fluoxetine, tended to remain in treatment programmes longer, yet with respect to weight gain the only medicine found to have an impact was olanzapine in one study, but without the same outcomes in psychiatric disease, where the evidence was quite contradictory. Hence, it is not possible to clarify the impact of treatment on weight-related rumination or obsession.

On safety and tolerability, the studies reported no severe or significant adverse effects; there was a single suicide attempt, in a patient on treatment with fluoxetine, which could not be attributed as such to the medicine. These results come from studies of a low methodological quality with four out of five having a high risk of bias; therefore, it is not possible to make evidence-based recommendations.

A 2007 systematic review by Bulik16 evaluated randomised studies that examined treatments with fluoxetine, amitriptyline and hormonal drugs, and concluded that there was no evidence to support the use of psychiatric drugs in the treatment of AN, since there was no significant impact on weight gain or psychological symptoms, and moreover the treatment groups had high rates of suspension. This systematic review identified a high risk of bias due to missing outcome data and some concerns due to deviations from the protocol, indicating that the landscape of evidence quality in relation to rates of suspension has not changed and remains a point of loss of methodological quality in studies of drug treatment of AN.

To conclude, with respect to the recommendations of the treatment guidelines, in a review by Resmark9 that summarised the most recently published German guidelines for the treatment of AN (January 2019), we found quite a complete synthesis that included the main recommendations of other recent guidelines such as the British (United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence [NICE]), Australian, German, Spanish, Danish and American (American Psychiatric Association [APA]) guidelines. More recent guidelines not included in Resmark's review are the Canadian guidelines on treating children and adolescents with eating disorders.26 In general, the guidelines place a great deal of emphasis on the lack of evidence on drug treatment and the major variability in recommendations for treatment with psychiatric drugs in patients with AN.

Compared to the scant evidence that exists for drug treatment, the usefulness of psychotherapy is clear as a cornerstone of AN treatment, though it still has a low level of evidence. Based on the different guides, it is concluded that, in general, cognitive behavioural therapy, the MANTRA and SSCM are equally effective and all are considered first-line treatments, but there is no evidence of the superiority of any treatment over the others.9

However, these results must be interpreted taking into account the limitations of the review. The main limitation was the paucity of studies and their small sample sizes, since this led to a decrease in power for detecting differences in the effects shown in the results due to the wide confidence intervals found in most analyses, added to the fact that the representativeness of the study samples was unclear. Another significant methodological deficiency in the placebo-controlled trials included herein was their brief duration: one of them had a duration of just six weeks and no follow-up period; this period was too short to evaluate the effects of an antidepressant in a condition with psychiatric disorders of a lasting nature and a typically slow course of recovery. In addition, the validity of dosing in most studies was questionable as testing of serum levels was not used to ensure treatment adherence, bearing in mind that poor adherence is a significant characteristic of patients with AN.

This study had several notable strengths, such as a specific review question; explicit eligibility criteria centred only on randomised controlled studies such as more empirical treatment evaluation studies; and an exhaustive, methodical literature search.

The evidence available at present on the efficacy and safety of AN treatment in different populations of patients on antipsychotics and antidepressants exhibits a great deal of variability in terms of results and shows a trend towards weight gain and improvement of AN-related psychiatric disease with administration of olanzapine and fluoxetine. However, these results cannot be generalised and applied with certainty to clinical practice in the population, due to the limited methodological designs found in most studies included in this systematic review, which had a shared problem of a high risk of bias in the interpretation of the results.

Given the seriousness and high mortality rates of AN in the population, in the coming years, this disease can be expected to remain a major public health problem; hence, the establishment of disease-modifying mental health plans will continue to merit priority. It is also essential to develop clinical trials of good methodological quality in order to determine the most appropriate treatment and enable evaluation of results with sufficient and suitable follow-up in this group of patients.

Consistent with previous reviews,16,27,28 our study concluded that there is contradictory information on the efficacy of psychiatric drugs for AN. Despite the lack of treatments of choice for AN, joint treatment with psychotherapy should be considered, and one treatment of choice is cognitive behavioural therapy.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.