Cotard’s syndrome is a rare psychiatric condition. As a result, current information is mainly based on reports and case series.

ObjectiveTo analyse the psychopathological characteristics and the grouping of the symptoms of the Cotard’s syndrome cases reported in the medical literature.

MethodsA systematic review of the literature of all reported cases of Cotard’s syndrome from 2005 to January 2018 was performed in the MEDLINE/PubMed database. Demographic variables and clinical characteristics of each case were collected. An exploratory factor analysis of the symptoms was performed.

ResultsThe search identified 86 articles, of which 69 were potentially relevant. After reviewing the full texts, 55 articles were selected for the systematic review, in which we found 69 cases. We found that the diagnosis of major depression (P < 0.001) and organic mental disorder (P = 0.004) were more frequent in the older group with Cotard’s syndrome. An exploratory factor analysis extracted 3 factors: psychotic depression, in which it includes patients with delusions of guilt (0.721), suicidal ideas (0.685), delusions of damnation (0.662), nihilistic delusions of the body (0.642), depression (0.522), and hypochondriacal delusions (0.535); delusive-hallucinatory, with patients who presented delusions of immortality (0.566), visual hallucinations (0.545) and nihilistic delusions of existence (0.451), and mixed, with patients who presented nihilistic delusions of concepts (0.702), anxiety (0.573), and auditory hallucinations (0.560).

ConclusionsThe psychopathology of Cotard’s syndrome is more complex than the simple association with the delusion of being dead, since it encompasses a factorial structure organised into 3 factors.

El síndrome de Cotard es de rara aparición en la clínica psiquiátrica. Debido a esto, la información actual se basa principalmente en reportes y series de casos.

ObjetivoAnalizar las características psicopatológicas y la agrupación de los síntomas de los casos de síndrome de Cotard reportados en la literatura médica.

MétodosSe realizó en la base de datos MEDLINE/PubMed una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura de todos los casos de síndrome de Cotard reportados desde 2005 hasta enero de 2018. Se recolectaron variables demográficas y las características clínicas de cada caso. Se realizó un análisis factorial exploratorio de los síntomas.

ResultadosLa búsqueda identificó 86 artículos, de los cuales 69 eran potencialmente relevantes. Luego de la revisión de los textos completos, se seleccionaron 55 artículos para la revisión sistemática, entre los cuales se hallaron 69 casos. En el grupo de más edad con síndrome de Cotard fueron más frecuentes los diagnósticos de depresión mayor (p < 0,001) y trastorno mental orgánico (p = 0,004). El análisis factorial exploratorio arrojó 3 factores: depresión psicótica, en la que se incluye a los pacientes con delirios de culpa (0,721), ideas suicidas (0,685), delirios de condena (0,662), delirio nihilista del cuerpo (0,642), depresión (0,522) y delirios hipocondriacos (0,535); delirante-alucinatorio, con pacientes que sufrían delirio de inmortalidad (0,566), alucinaciones visuales (0,545) y delirio nihilista de la existencia (0,451), y mixto, con pacientes que sufrían delirio nihilista de los conceptos (0,702), ansiedad (0,573) y alucinaciones auditivas (0,560).

ConclusionesLa psicopatología del síndrome de Cotard es más compleja que la simple asociación con el delirio de estar muerto, ya que abarca una estructura factorial organizada en 3 factores.

Cotard’s syndrome is an uncommon psychiatric condition the main characteristic of which is nihilistic delusions, in which patients deny their own existence or the existence of parts of their bodies.1 It was first reported by Jules Cotard in 1880. Since then, the concept of this syndrome has passed through various vicissitudes.2

At present, Cotard's syndrome is usually considered a monothematic delusion.3 We believe this conceptualisation is erroneous, as it does not capture the original concept set out by Cotard, to whom this condition consisted of not only a belief that one is dead, but also anxiety, agitation, severe depression, suicidal behaviour and other delusional ideas (immortality, enormity, blame, damnation and hypochondria).2,4

In the medical literature, this syndrome is primarily explored through case reports; few studies have analysed case series. To our knowledge, the study that retrospectively analysed the largest number of cases was a study by Berrios et al.5, who reviewed 100 cases of patients with this syndrome reported between 1880 and 1993. They performed an exploratory analysis of psychopathological symptoms and found three factors: a) psychotic depression: anxiety, delusion of guilt, depression and auditory hallucinations; b) Cotard's syndrome type I: hypochondriacal delusions and nihilistic delusions relating to the body, concepts and existence; and c) Cotard's syndrome type II: anxiety, delusions of immortality, auditory hallucinations, nihilistic delusions relating to existence and suicidal behaviours. Cotard's syndrome type I would be the pure form of the syndrome, with nosological origins in delusions, not in affective disorders.5 This grouping has not been corroborated in other more recent cases. Subsequently, Consoli et al.6 supplemented the study by Berrios et al.5 by retrospectively studying another 38 cases reported between 1994 and 2005. We concur with the finding of Berrios et al.2 that suitable study of the neurological foundations of Cotard's syndrome requires mapping of its clinical characteristics and basic clinical correlations.

This systematic review was undertaken with the objective of analysing the psychopathological characteristics and groupings of symptoms in the cases of Cotard's syndrome reported in the medical literature since Consoli et al.6 conducted their study.

MethodsThis systematic review was done in accordance with PRISMA statement guidelines.7 The MEDLINE database was searched via the PubMed interface for all cases of Cotard's syndrome reported between 1 January 2005 and 24 January 2018 using the following terms: (Cotard's Syndrome) OR (Cotard's delusion) OR (Cotard syndrome) OR (Cotard delusion) OR (nihilistic delusion). Articles written in English or Spanish were selected. The principal investigator (JHV) screened the eligible articles. First, the principal investigator reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the articles found, then, two investigators (JHV and JBD) reviewed the full text of the potentially relevant articles.

The methodology applied by Berrios et al. was used5 (with the authorisation of the authors). Each case was searched for the following variables: age; sex; anxiety; depression; nihilistic delusions (relating to concepts, relating to existence and relating to the body); hypochondriacal delusions; delusions of immortality, damnation and other delusions; auditory and visual hallucinations; catatonic symptoms; suicidal ideas and/or acts; and the diagnosis given by the authors of the case reports. Two investigators (JHV and JBD) extracted the data independently, then resolved any discrepancies by consensus.

An independent investigator (JDO) performed the statistical analysis. Percentages for each symptom and average ages were determined using descriptive statistical techniques. Differences in frequency of symptoms between males and females were explored using a two-proportion z-test. In addition, patients were split into age groups to analyse the frequency of the diagnoses using the proportion difference test.

An exploratory factor analysis was performed with symptoms as variables using the principal component analysis method, then adjusted using varimax rotation. The number of factors was determined using the criterion of an eigenvalue >1.

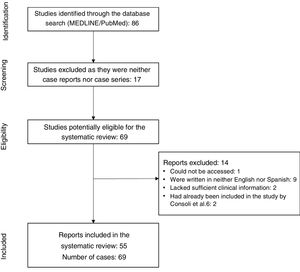

ResultsThe initial search yielded a total of 86 articles. After 17 articles that were neither case reports nor case series were excluded, 69 articles with reports of cases of Cotard's syndrome remained.8–74 These case reports were then reviewed and 14 more articles were excluded as the report could not be accessed63, was written in neither English nor Spanish64–72, lacked sufficient clinical data73,74 or had been included in the review by Consoli et al.6,75,76. By investigator agreement, 55 articles were included in this study8–62 (Fig. 1).

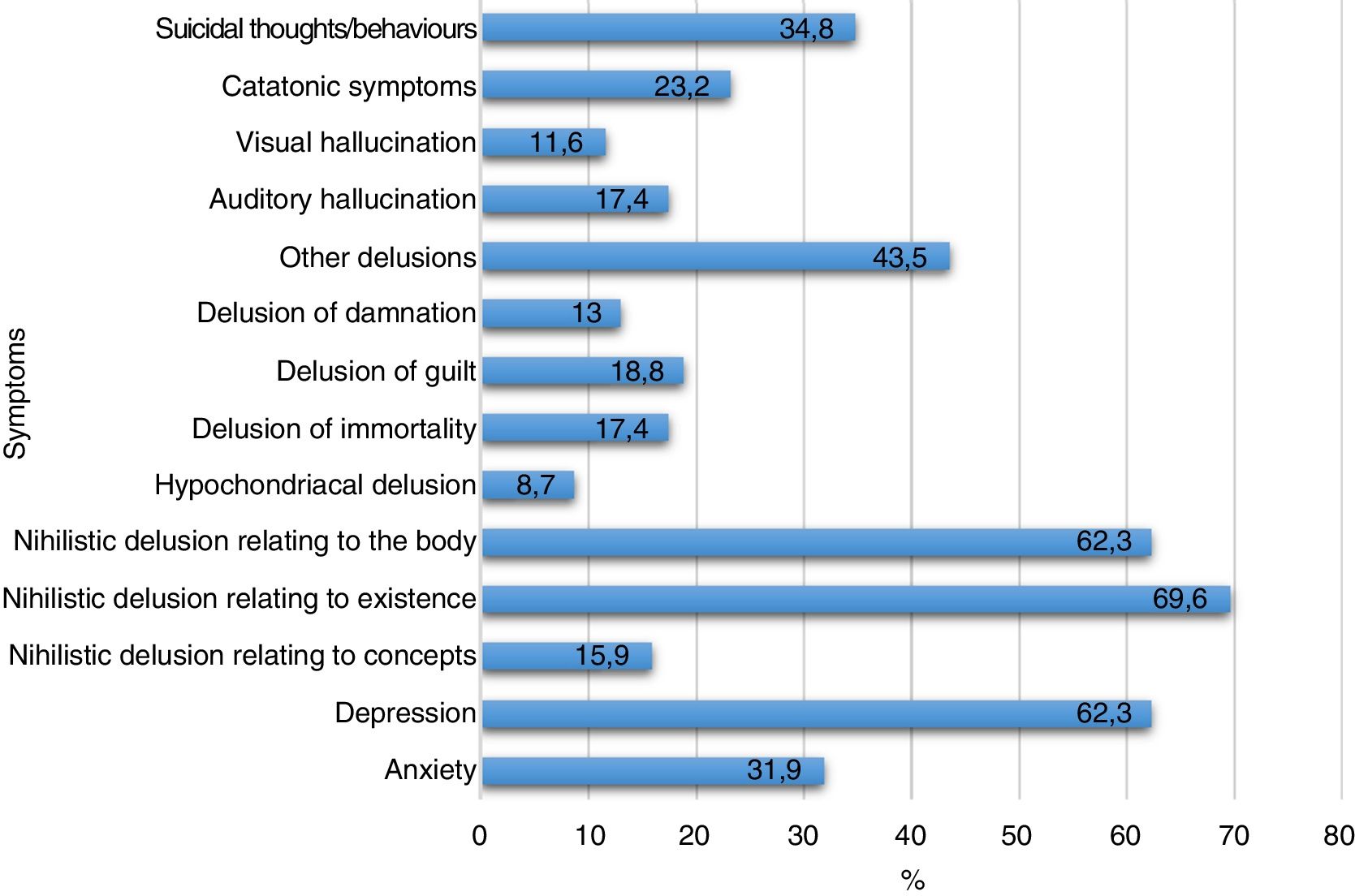

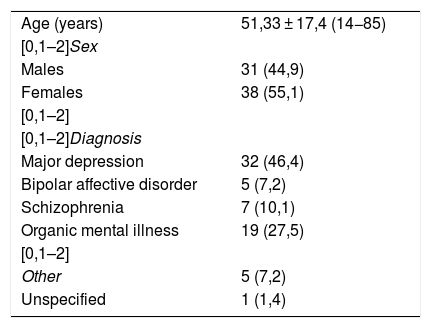

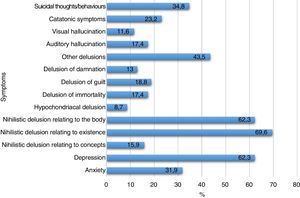

The sample included 69 patients (31 males and 38 females), with a mean age of 51.33 ± 17.4 years. The most common diagnosis was major depression (46.4%) (Table 1). The most common symptoms were nihilistic delusion relating to existence (69.6%), nihilistic delusion relating to the body (62.3%) and depression (62.3%). Fig. 2 shows the frequency of the other symptoms.

Characteristics and diagnosis of 69 patients with Cotard’s syndrome reported between 2005 and 2018.

| Age (years) | 51,33 ± 17,4 (14−85) |

| [0,1–2]Sex | |

| Males | 31 (44,9) |

| Females | 38 (55,1) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| [0,1–2]Diagnosis | |

| Major depression | 32 (46,4) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 5 (7,2) |

| Schizophrenia | 7 (10,1) |

| Organic mental illness | 19 (27,5) |

| [0,1–2] | |

| Other | 5 (7,2) |

| Unspecified | 1 (1,4) |

Values express n (%) or mean ± standard deviation.

No significant differences were found between males and females in terms of symptom frequencies. Once the participants were divided into two age groups (≤25 and >25), the older group was found to have a higher rate of diagnosis of major depression (32 versus 2; p < 0.001) and organic mental illness (16 versus 3; p = 0.004). Within the group with a diagnosis of major depression, no significant differences in symptoms were found between males and females or between age groups. When only patients with a diagnosis of organic mental illness were considered, no relationships were found between symptoms and age group or between symptoms and sex.

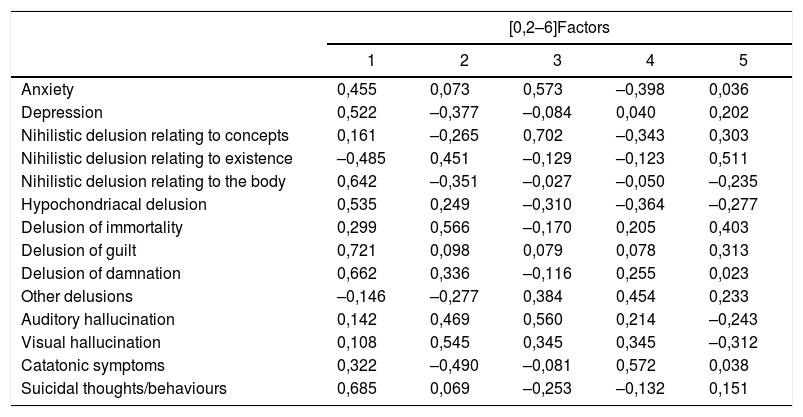

Table 2 shows the exploratory factor analysis which was determined through a sediment graph. Variables were reduced by grouping them into three factors: 1, psychotic depression, with an eigenvalue of 3.112 and a variance of 22.23%, containing the symptoms of delusion of guilt (0.721), suicidal ideas (0.685), delusion of damnation (0.662), nihilistic delusion relating to the body (0.642), depression (0.522) and hypochondriacal delusion (0.535); 2, delusional/hallucinatory depression, with an eigenvalue of 1.88 and a variance of 13.48, containing the symptoms of delusion of immortality (0.566), visual hallucinations (0.545) and nihilistic delusion relation to existence (0.451); and 3, mixed, with an eigenvalue of 1.64 and a variance of 11.72, containing the symptoms of nihilistic delusion relating to concepts (0.702), anxiety (0.573) and auditory hallucinations (0.560). Varimax rotation did not improve the values for the symptoms in the components.

Exploratory factor analysis of 14 symptoms.

| [0,2–6]Factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Anxiety | 0,455 | 0,073 | 0,573 | –0,398 | 0,036 |

| Depression | 0,522 | –0,377 | –0,084 | 0,040 | 0,202 |

| Nihilistic delusion relating to concepts | 0,161 | –0,265 | 0,702 | –0,343 | 0,303 |

| Nihilistic delusion relating to existence | –0,485 | 0,451 | –0,129 | –0,123 | 0,511 |

| Nihilistic delusion relating to the body | 0,642 | –0,351 | –0,027 | –0,050 | –0,235 |

| Hypochondriacal delusion | 0,535 | 0,249 | –0,310 | –0,364 | –0,277 |

| Delusion of immortality | 0,299 | 0,566 | –0,170 | 0,205 | 0,403 |

| Delusion of guilt | 0,721 | 0,098 | 0,079 | 0,078 | 0,313 |

| Delusion of damnation | 0,662 | 0,336 | –0,116 | 0,255 | 0,023 |

| Other delusions | –0,146 | –0,277 | 0,384 | 0,454 | 0,233 |

| Auditory hallucination | 0,142 | 0,469 | 0,560 | 0,214 | –0,243 |

| Visual hallucination | 0,108 | 0,545 | 0,345 | 0,345 | –0,312 |

| Catatonic symptoms | 0,322 | –0,490 | –0,081 | 0,572 | 0,038 |

| Suicidal thoughts/behaviours | 0,685 | 0,069 | –0,253 | –0,132 | 0,151 |

1: psychotic depression; 2: delusional/hallucinatory; 3: mixed.

Five factors extracted. Extraction method: principal factor analysis.

Current knowledge of Cotard’s syndrome is based on case reports and case series with few patients. To our knowledge, this is the second retrospective study with the largest sample of patients with Cotard's syndrome.

The mean age of the patients was 51.33 years; this was similar to that reported in the study by Berrios et al.5. According to Séglas77, these patients’ psychopathology “manifests in adulthood, most often towards mid-life”.

The diagnoses of major depression and organic mental illness had a significant relationship with age (>25 years). This result contrasted with that reported by Consoli et al.6, who found that, in young patients with Cotard's syndrome (≤25 years of age), the diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder was more common and the risk of having this diagnosis was up to nine times higher (p < 0.0001).

Regarding symptom frequencies, nihilistic delusions were the most commonly identified symptoms. Cases may be of three types: a) nihilistic delusions relating to existence, in which patients deny their own somatic and/or spiritual existence; b) nihilistic delusions relating to the body, in which patients deny the existence of parts of their bodies, saying they do not have organs or are decomposed or “rotten on the inside”15; and c) nihilistic delusions relating to concepts, which affect metaphysical representations made by patients, who may state that nothing exists or deny other people's identities10. Interestingly, delusions of damnation, guilt and immortality were reported at a lower frequency than in cases from 1880 to 1993.5 This may be due to the fact that: a) in the course of the 20th century, Cotard’s syndrome, along with other clinical phenomena, underwent semantic degradation, such that at the present time there is a tendency to consider Cotard’s syndrome as a monothematic delusion, which is detrimental to preparing a more detailed pathophysiological report2,77,78; and b) general changes have occurred in the moral and religious culture of the Western world. Prior reviews did not take catatonic symptoms into account5,6; these were found in 23.2% of patients. Catatonic symptoms in Cotard's syndrome have classically been reported as uncommon. For some authors this would be due to the rarity of this association32, whereas for others these symptoms would be more common43. This could be explained, in part, by the fact that catatonic symptoms are often underdiagnosed for lack of investigation. In a worst-case scenario, this could lead to ineffective treatment resulting in serious complications for the patient’s life due to prolonged immobility and dehydration.

The exploratory factor analysis yielded three factors: psychotic depression, delusions/hallucinations and mixed. The psychotic depression factor included patients with depression, and the others may be psychopathological symptoms with said depression at their core. It could also be imagined that the delusional symptoms grouped in this factor have a relationship with the course of Cotard's syndrome (e.g. hypochondriacal delusions could develop into nihilistic delusions relating to the body and delusions of guilt, then delusions of damnation). The delusions/hallucinations factor features symptoms of depression, whereas the mixed factor features symptoms of anxiety, hallucinations and delusions. These results partly overlap with those reported by Berrios et al.5 Hence, Cotard’s syndrome may be thought to show factor coherence independent of time and space. These results have: a) certain implications for psychopathology, as there is a group of patients with Cotard’s syndrome whose psychopathology features not affective disorders, but instead phenomena of hallucinations/delusions — Saavedra79 noted that this may be seen in patients with schizophrenic psychosis, and that the psychopathology would be distorted by the phenomena of hallucinations and delusions thereof, and proposed the name “pseudo-Cotard's syndrome” for this form of presentation, as a variant of cenesthopathic schizophrenia — and b) certain implications for treatment, as patients with Cotard's syndrome with delusions/hallucinations probably do not show a suitable response to antidepressant treatment, such that an antipsychotic agent must be used5. Our clinical experience has indicated that taking this factor differentiation into consideration optimises treatment and treatment response.11,15

This study has significant limitations. Uncontrolled secondary sources were analysed, meaning that its findings were limited by the quality of the cases reported, which was not uniform. A systematic review of reported cases could not find any strong associations. However, if some hypotheses can be identified for future studies, psychiatrists should take into consideration the cases reported in the literature indicating that Cotard's syndrome is not exclusive to psychotic depression.

ConclusionsCotard’s syndrome psychopathology is more complex than the mere association with the “delusion of being dead” that has marked the approach to the disease in recent decades. The cases reported between 2005 and 2018 showed a significant relationship between an age >25 years and a diagnosis of major depression or organic mental illness. The exploratory factor analysis of symptoms yielded three factors: psychotic depression, delusions/hallucinations and mixed. These had already been reported in another study with a different patient sample; hence, it is possible to consider these factors to exhibit factor coherence independent of space and time. These results would have implications for these patients’ psychopathology and treatment.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Huarcaya-Victoria J, la Torre JB-D, De la Cruz-Oré J. Estructura factorial del Síndrome de Cotard: revisión sistemática de reportes de caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:187–193.