There are few studies that examine the factors associated with the different levels of health anxiety in medical students. The objective was to determine the factors associated with the levels of health anxiety in medical students in 2018.

MethodsAn analytical cross-sectional study was carried out with 657 medical students from a private Peruvian university. Participants answered a questionnaire from which information was collected regarding levels of health anxiety (SHAI). For the analysis, linear regression was used to calculate crude and adjusted betas, and their 95% confidence intervals.

ResultsThe mean health anxiety score was 14 ± 6.7. An association between health anxiety and the year of study is reported, with the second year showing the highest scores. In addition, an association between health anxiety and smoking is highlighted, as there are higher levels in occasional smokers, as well as a weak inverse correlation with age. No association was found with sex, place of birth, or having a first-degree relative that is a doctor or health worker.

ConclusionsThe present study showed that age, year of studies and smoking are associated with health anxiety levels. More studies are required, especially of a longitudinal nature.

Existen pocos estudios que examinen los factores asociados con los distintos niveles ansiedad por la salud en los estudiantes de Medicina. El objetivo es determinar los factores asociados con los niveles de ansiedad por la salud en estudiantes de Medicina en el año 2018.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio transversal analítico con 657 estudiantes de Medicina de una universidad privada peruana. Los participantes respondieron a un cuestionario donde se recopiló la información respecto a los niveles de ansiedad por la salud (SHAI). Para el análisis se empleó la regresión lineal para calcular los betas, brutos y ajustados, y sus intervalos de confianza del 95%.

ResultadosEl promedio de la puntuación de ansiedad por la salud fue de 14 ± 6,7. Se reporta una asociación entre la ansiedad por la salud y el año de estudio, y el segundo año es el que revela puntuaciones más altas. Además, pone de manifiesto la asociación entre la ansiedad por la salud y el consumo de tabaco, pues hay niveles más altos en los fumadores ocasionales, así como una débil correlación inversa con la edad. No se revela asociación con el sexo, el lugar de nacimiento, tener un familiar de primer grado médico o un familiar de primer grado personal saiario.

ConclusionesEl presente estudio evidenció que la edad, el año de estudios y el consumo de tabaco se asocian con los niveles de ansiedad por la salud. Se requieren más estudios, especialmente de naturaleza longitudinal.

The state of excessive, unrealistic and persistent worry about suffering from a disease is known as health anxiety (HA)1,2 and is a not-uncommon condition.2 In 1994, the American Psychiatric Association defined high levels of HA as hypochondria or hypochondriasis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV).3 In 2013, however, the DSM-54 replaced hypochondriasis with illness anxiety disorder (IAD) and somatic symptom disorder (SSD). Nevertheless, a preference for the term HA has continued in clinical practice as it is considered less derogatory. HA levels high enough to classify a subject as a hypochondriac, and to make the diagnosis of IAD or SSD, must be determined by a specialist, such as a psychiatrist.2 Despite that, to study HA, various tools have been developed over the years to help measure it and, in some cases, set a cut-off point for determining whether a person’s HA levels are high enough to be compatible with hypochondriasis.5

Somewhere in the range of 5%–30% of outpatient clinic patients and 2%–13% of adults in general have been reported to have signs of HA.1 The average degree of HA measured by the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI) is 12.4 ± 6.8 points in the non-clinical population, 22.9 ± 11.0 in the clinical population, and 32.5 ± 9.6 in the hypochondriacal population.5 In studies carried out on university Psychology students, averages of 10.8 ± 6.4 points have been recorded in students from Midwestern University in the United States,6 12.0 ± 6.8 in students from the University of North Carolina,7 12.2 ± 6.5 in those from a university in the southern United States,8 and 13.4 ± 5.3 in Canadian university students.9 High levels of HA are more common in early adulthood3; they affect males and females equally and are not associated with marital status.10 HA is also known to be worse in the unemployed and in less educated patients.10 The DSM-5 lists high levels of HA as a non-pathological response to a serious illness.4

Health science students are one population which seems to be particularly affected by HA; a systematic review of hypochondriacal symptoms in Chinese students found a high prevalence (28%).11 Variations in HA have been found in medical students according to gender and year of studies, but the differences were not reported statistically significant.11,12 Young people entering higher education are in a process of trying to adapt to the university environment, while being influenced by factors such as living away from home, having new and different friendships, and typical age-related changes. All these factors have an impact on their physical and mental health in a period in which they are establishing their responsibilities and individual personalities.13 In addition, medical students are subjected to constant stress associated with intense study sessions, a heavy workload, a competitive environment and new clinical experiences.14 A study on well-being and mental health among medical students in Canada revealed that 36% of them had sought professional help for some mental illness. The most commonly reported were anxiety disorders, and 83% stated their medical studies were a major source of stress.15 A study on psychological morbidity conducted in third-year medical students in Egypt reported that a significantly high proportion of students (59.9%) had an ongoing psychiatric condition. However, there was no statistically significant difference between psychological morbidity and any of the sociodemographic variables. The most prevalent psychiatric diagnosis was depression (47.9%), followed by generalised anxiety disorder (44.9%) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (44.4%), and the least prevalent was anorexia nervosa (0.7%).16 Factors such as depression, anxiety, stress, low income, gender, and being in the early stages of medical training were associated with poorer mental health and quality of life.17,18 Poor quality of life among medical students is associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, psychological disturbance and academic failure, which could affect the future care of their patients.19,20 This data reaffirms the urgent need to implement counselling and preventive mental health services as an integral part of the usual clinical facilities that serve medical students.

It is thought that medical students start perceiving symptoms as medical signs when they learn about new illnesses. Reactions referred to as medical student illness, nosophobia or medical student hypochondria are often seen as a form of transient hypochondriasis.14 Medical students who believe they have contracted a certain disease identify cases more easily and selectively, as they arouse interest and stay in their minds.13,14 There is very little in the way of epidemiological data aimed at preventing the consequences of lack of HA prevention in medical students in the short-term and over the long-term in these future doctors. If they are not diagnosed and/or do not receive adequate cognitive-behavioural therapy, there could be significant lasting effects.21,22

Depending on a person’s degree of HA, not preventing this condition could have important implications for their health. As medical students are prone to the above-mentioned transient hypochondriasis,14 this condition could interfere with their appropriate professional and social development, from spending too much time and financial resources investigating possible diseases.23 They might also be predisposed to perform tests, which would waste resources24,25 and cause unnecessary exposure to adverse effects. It could also lead to self-medication26 and, if that reaches high levels, it could become a risk factor for suicide.2 All of the above underlines the importance of prevention, diagnosis and timely treatment of HA.

Despite the apparent serious nature and the great economic cost of HA, relatively few epidemiological studies have examined the extent of the symptoms or sociodemographic and risk factors associated with HA, with data on medical students particularly lacking. In addition, there is not much information on the subject in Latin America, so we do not know how exactly the phenomenon works in this region. The lack of evidence limits understanding of HA and makes it difficult for healthcare professionals to formulate health policies for adequate planning and funding of treatment and prevention services to reduce the high levels of this condition.10 Therefore, the general aim of this study was to determine the factors associated with HA levels (measured by the SHAI) in medical students from a private university in Peru in 2018. Based on results published previously,1,3,10 the hypothesis is that gender, age, year of studies, place of birth, smoking, and having a first-degree relative who is a health worker and/or doctor are all factors associated with HA in medical students. The specific objectives were to determine the level of HA in these students and to detect any differences in their levels of HA according to gender, age, year of studies, place of birth and smoking, and in relation to having a first-degree relative doctor and/or healthcare worker.

MethodsStudy design and contextThis was an analytical cross-sectional study based on surveys applied to students from a private university in Lima, Peru. The surveys were carried out from 9 to 19 November 2018.

Study populationThe target population was medical students from a health sciences faculty of a private Peruvian university. We surveyed all medical students from second to fourth year who met the inclusion criteria: being over 18 years old, enrolled in the cycle and present when the survey was applied.

As a census was conducted, a sample size calculation was not strictly necessary.

The exclusion criteria were refusal to give informed consent and an incomplete survey, i.e. those that did not include the outcome, gender or age.

Measurement variables and sourcesHA was considered the primary dependent variable of the study, and was defined as the state of excessive, unrealistic and persistent worry about suffering from a disease in the last six months. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI)5 was used to measure this variable and consists of 18 questions divided into two sections, with 14 questions in the main section and four in the negative consequences section. Each question has four options, scoring from 0 to 3 points, for a total score between 0 and 54 (from 0 to 42 for the main section and 0–12 for the negative consequences section). This instrument has versions validated in Spanish27,28 and for this study we used the version adapted and validated in a South American country (Vallejo-Medina P, 2018, unpublished). A confirmatory factor analysis was performed in Colombia and adequate construct validity was reported. Cronbach’s alpha index was used to estimate reliability, with a total scale reliability of 0.82 and good internal consistency.

To complete the analysis, HA was categorised. We used a threshold of 27 points or above in the SHAI to identify students who reported scores compatible with hypochondria. We chose this cut-off point because it provided the best balance between sensitivity and specificity.5

The covariates studied were: gender; year of studies (from second to sixth year); age in years; place of birth (Lima, the provinces or another country); smoking (regular smoker, occasional smoker, passive smoker or non-smoker); and history of first-degree relative doctor or healthcare worker.

Information collectionThe potential number of students who met the inclusion criteria for the survey was calculated. We then asked for authorisation to enter the classrooms five minutes before the end of classes in order to apply the surveys. Part of the time was spent reading the informed consent form, and they then went ahead with the survey. Students who did not give informed consent were excluded, and incomplete surveys were not entered into the database.

Data processing and analysisOnce the data collection was completed, the data was double entered in MS Excel, each database was reviewed separately, and then the two databases were compared. After that the information was exported to the STATA 15.0 program for Windows (Stata Corp., United States) for the corresponding analysis. For univariate analysis, the median [interquartile range] was used for the quantitative variables age and SHAI score (total, main section and negative consequences). We also calculated the mean ± standard deviation of the SHAI scores. We used frequencies and percentages for the categorical variables gender, place of birth, year of studies, first-degree relative healthcare worker or doctor, and smoking.

For the bivariate analysis of HA levels, three statistical tests were used. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to cross-match the SHAI scores with gender and first-degree relative healthcare worker or doctor. The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to cross-match the SHAI scores with place of birth, year of studies and smoking, after which a post-hoc analysis was performed using the kwallis2 command in Stata. The Spearman correlation was used to cross-match the SHAI scores with age. Lastly, for the analysis of multiple variables, linear regression was used to calculate the betas and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). The crude model was calculated as part of the analysis, before adjusting the model for the other variables (using bivariate linear regression initially y = β0 + β1 × 1). To select the variables to enter into the adjusted model, we used the epidemiological criterion, i.e. we took into account the sociodemographic variables and the relevant previous history, as reported by previous studies. Linear regression assumptions were tested through residual analysis. Collinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF).

Ethical, administrative and regulatory aspectsThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas [Peruvian University of Applied Sciences]. In addition, the participants gave their informed consent after the purpose of the study and the type of questions they would be asked in the survey were explained to them. This study did not involve any risks for the respondents, as they were only required to complete a survey anonymously. Respondents freely chose to take part and were given the option to stop the survey if they felt it was necessary. After application of the survey, they were provided with pamphlets with information on the subject and contact numbers.

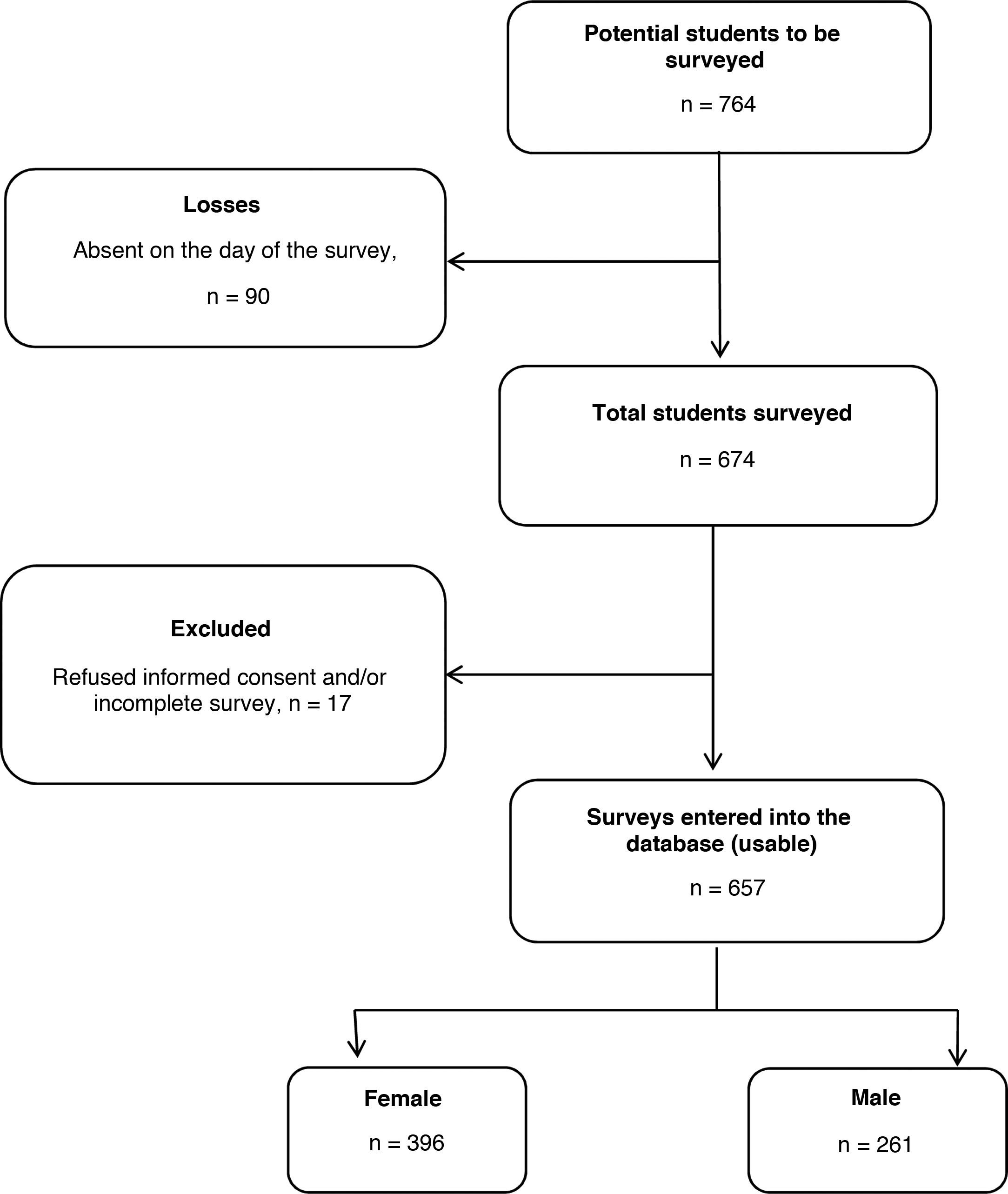

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the surveyed studentsA total of 674 medical students (88.2% of the total potential surveys based on matriculations) met the inclusion criteria and completed the survey. We excluded 17 surveys from the analysis because one or more variables of interest were incomplete. In the end, 657 surveys were analysed (86.0% of the total potential surveys and 97.5% of the total number of students present in the classroom at the time of the survey), 26.2% from second-year students, 20.2% third-year, 28.5% fourth-year, 11.1% fifth-year and 14.0% sixth-year (Fig. 1).

Of all the surveys analysed, 60.3% corresponded to female students. The median age of the participants was 21 [20–23] and more than half (63.8%) stated Lima as their place of birth (Table 1).

Characteristics of the participating students (n = 657).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 396 (60.3) |

| Male | 261 (39.7) |

| Age (years) | 21 [20–23] |

| Place of birth | |

| Lima | 419 (63.8) |

| The provinces | 216 (32.9) |

| Other country | 22 (3.3) |

| Year of studies | |

| Second | 172 (26.2) |

| Third | 133 (20.2) |

| Fourth | 187 (28.5) |

| Fifth | 73 (11.1) |

| Sixth | 92 (14) |

| First degree relative doctor | |

| Yes | 173 (26.3) |

| No | 484 (73.7) |

| First degree relative healthcare worker | |

| Yes | 287 (43.7) |

| No | 370 (56.3) |

| Smoking | |

| Regular smoker | 19 (2.9) |

| Occasional smoker | 123 (18.7) |

| Passive smoker | 273 (41.6) |

| Non-smoker | 242 (36.8) |

| Total SHAI score | 13 [9–18] |

| SHAI, main section | 11 [8–15] |

| SHAI, negative consequences | 2 [1–3] |

SHAI: Short Health Anxiety Inventory.

A majority 73.7% of the participants stated they did not have a first-degree relative doctor, and 43.7% did not have a first-degree relative healthcare worker. As regards smoking, the majority reported being passive smokers (41.6%) or non-smokers (36.8%) (Table 1).

Analysis of the HA score obtained from the SHAI showed a median of 13 [9–18] and a mean of 14.0 ± 6.7. In addition, 29 participants (4.41%) reported levels compatible with hypochondriasis (information not reported in the tables).

Factors associated with health anxiety. Bivariate analysisA weak negative correlation was found between HA measured by the SHAI and age (ρ = –0.15; p < 0.001); an association was also found with smoking (p = 0.02) where, according to the post-hoc analysis (not shown in the tables), the difference between occasional smokers and non-smokers was significant (p < 0.001). An association was also found with the year of studies (p < 0.001); second year had the highest score and, according to the post-hoc analysis (not shown in the tables), the differences were significant between second and fifth (p < 0.001) and sixth year (p < 0.001); between third and fifth year (p < 0.001), and between fourth and fifth year (p < 0.001). No association was found with gender, place of birth, first-degree relative doctor or first-degree relative healthcare worker (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Factors associated with health anxiety, bivariate model (n = 657).

| Variables | Total SHAI score | p | SHAI, main section | p | SHAI, negative consequences | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 13 [10–18] | 0.61 | 11 [8–15] | 0.22 | 2 [1–3] | 0.12 |

| Male | 13 [9–18] | 11 [7–15] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Age | ρ = –0.15 | <0.001 | ρ = –0.15 | <0.001 | ρ = –0.06 | 0.10 |

| Place of birth | ||||||

| Lima | 13 [9–17] | 0.94 | 11 [8–15] | 0.95 | 2 [1–3] | 0.62 |

| The provinces | 13 [9–18] | 11 [7–16] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Other country | 12.5 [10–17] | 11 [8–14] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Year of studies | ||||||

| Second | 16 [11–20] | <0.001 | 13 [9–18] | <0.001 | 2 [1–3] | 0.01 |

| Third | 13 [10–18] | 12 [8–15] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Fourth | 13 [10–17] | 11 [8–15] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Fifth | 10 [7–13] | 8 [6–12] | 1 [0–2] | |||

| Sixth | 11 [7.5–16] | 9 [6.5–14] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| First degree relative doctor | ||||||

| Yes | 12 [10–16] | 0.45 | 10 [8–14] | 0.47 | 2 [1–3] | 0.61 |

| No | 13 [9–18] | 11 [8–16] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| First degree relative healthcare worker | ||||||

| Yes | 13 [10–18] | 0.71 | 11 [8–15] | 0.66 | 2 [1–3] | 0.99 |

| No | 13 [9–18] | 11 [8–15] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Regular smoker | 11 [10–19] | 0.02 | 10 [8–14] | 0.05 | 2 [0−3] | 0.08 |

| Occasional smoker | 15 [10–20] | 12 [8–18] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Passive smoker | 13 [10–18] | 11 [8–15] | 2 [1–3] | |||

| Non-smoker | 13 [9–17] | 11 [7–14] | 1 [1–3] | |||

SHAI: Short Health Anxiety Inventory.

Values are expressed in terms of median [interquartile range].

In the scores for the main section of the SHAI, a weak negative correlation was found with age (ρ = –0.15; p < 0.001); an association was also found with the year of studies (p < 0.001); second year had the highest, and the differences were significant between second and fourth (p = 0.002), fifth (p < 0.001) and sixth year (p < 0.001), between third and fifth year (p < 0.001) and between fourth and fifth year (p < 0.001). No association was found with gender, place of birth, first-degree relative doctor, first-degree relative healthcare worker or smoking (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

In the scores for the negative consequences section of the SHAI, the only association found was with the year of studies (p = 0.01). According to the post-hoc analysis (not shown in the tables), the difference was significant between second and fifth year (p < 0.001) and between fourth and fifth year (p = 0.002). No association was found with gender, age, place of birth, first-degree relative doctor, first-degree relative healthcare worker or smoking (p > 0.05) (Table 2).

Factors associated with health anxiety. Multivariate analysisIn the multiple variables model (adjusted for gender, place of birth, year of studies, first-degree relative doctor and smoking), an association was found between HA measured by the SHAI and the year of studies, and there was a significant difference between the occasional smoker and the non-smoker. These associations were also found with the main section of the SHAI and the negative consequences section separately. No association was found with gender, place of birth, or first-degree relative doctor (p > 0.05) in any of the cases (Tables 3 and 4).

Factors associated with health anxiety, multivariate analysis.

| Variables | SHAI, total scorea, β (95% CI) | p | Corrected total SHAI scoreb, β (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Male | –0.3 (–1.3 to 0.8) | 0.62 | –0.1 (–1.2 to 0.9) | 0.78 |

| Age | –0.3 (–0.6 to –0.1) | 0.01 | ||

| Place of birth | ||||

| Lima | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| The provinces | –0.1 (–1.2 to 1.0) | 0.85 | –0.1 (–1.1 to 1.0) | 0.93 |

| Other country | –0.8 (–3.7 to 2.1) | 0.59 | –0.4 (–3.2 to 2.5) | 0.80 |

| Year of studies | ||||

| Second | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Third | –2.1 (–3.6 to –0.6) | 0.01 | –2.0 (–3.5 to –0.5) | 0.01 |

| Fourth | –1.5 (–2.9 to –0.1) | 0.03 | –1.6 (–3,0 to –0.2) | 0.03 |

| Fifth | –5.2 (–7.0 to –3.4) | <0.001 | –5.2 (–7.0 to –3.3) | <0.001 |

| Sixth | –2.9 (–4.6 to –1.3) | 0.001 | –3.0 (–4.6 to –1.3) | 0.001 |

| First degree relative doctor | ||||

| Yes | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| No | 0.8 (–0.3 to 2.0) | 0.16 | 0.8 (–0.4 to 1.9) | 0.18 |

| First degree relative healthcare worker | ||||

| Yes | Reference | – | ||

| No | –0.02 (–1.1 to 1.0) | 0.97 | ||

| Smoking | ||||

| Passive smoker | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Occasional smoker | 1.1 (–0.3 to 2.5) | 0.13 | 1.4 (–0.03 to 2.8) | 0.05 |

| Regular smoker | –0.8 (–3.9 to 2.3) | 0.62 | –0.3 (–3.4 to 2.8) | 0.86 |

| Non-smoker | –1.1 (–2.2 to 0.1) | 0.72 | –0.9 (–2.0 to 0.3) | 0.13 |

Factors associated with the health anxiety dimensions, multivariate analysis.

| Variables | SHAI, main sectiona, β (95% CI) | SHAI, corrected main sectionb, β (95% CI) | SHAI, negative consequencesa, β (95% CI) | SHAI, corrected negative consequencesb, β (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||||||

| Female | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Male | –0.5 (–1.4 to 0.4) | 0.26 | –0.4 (–1.3 to 0.5) | 0.37 | 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.6) | 0.13 | 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.6) | 0.12 |

| Age | –0.3 (–0.5 to –0.1) | 0.002 | –0.02 (–0.1 to 0.04) | 0.50 | ||||

| Place of birth | ||||||||

| Lima | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| The provinces | 0.02 (–0.9 to 0.9) | 0.96 | 0.1 (–0.8 to 1.0) | 0.88 | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.45 | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.49 |

| Other country | –0.6 (–3.0 to 1.8) | 0.61 | –0.2 (–2.6 to 2.1) | 0.84 | –0.2 (–1.0 to 0.7) | 0.72 | –0.1 (–1.0 to 0.8) | 0.79 |

| Year of studies | ||||||||

| Second | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Third | –1.8 (–3.0 to –0.6) | 0.01 | –1.7 (–3.0 to –0.5) | 0.01 | –0.3 (–0.8 to 0.1) | 0.19 | –0.3 (–0.8 to 0.2) | 0.21 |

| Fourth | –1.4 (–2.6 to –0.3) | 0.01 | –1.5 (–2.6 to –0.3) | 0.01 | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.4) | 0.80 | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.3) | 0.69 |

| Fifth | –4.3 (–5.8 to –2.8) | <0.001 | –4.3 (–5.8 to –2.8) | <0.001 | –0.9 (–1.5 to –0.3) | 0.001 | –0.9 (–1.5 to –0.3) | 0.002 |

| Sixth | –2.9 (–4.3 to –1.5) | <0.001 | –2.9 (–4.3 to –1.5) | <0.001 | –0.0002 (–0.5 to 0.5) | 0.999 | –0.03 (–0.5 to 0.5) | 0.90 |

| First-degree relative doctor | ||||||||

| Yes | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| No | 0.6 (–0.4 to 1.6) | 0.21 | 0.6 (–0.4 to 1.5) | 0.25 | 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.6) | 0.21 | 0.2 (–0.1 to 0.6) | 0.20 |

| First-degree relative healthcare worker | ||||||||

| Yes | Reference | – | Reference | – | ||||

| No | –0.1 (–0.9 to 0.8) | 0.90 | 0.04 (–0.3 to 0.4) | 0.80 | ||||

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Passive smoker | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – | Reference | – |

| Occasional smoker | 0.8 (–0.4 to 2.0) | 0.17 | 1.0 (–0.1 to 2.2) | 0.08 | 0.3 (–0.1 to 0.7) | 0.20 | 0.3 (–0.1 to 0.8) | 0.13 |

| Regular smoker | –0.7 (–3.3 to 1.9) | 0.62 | –0.1 (–2.7 to 2.5) | 0.93 | –0.1 (–1.1 to 0.8) | 0.79 | –0.2 (–1.1 to 0.8) | 0.72 |

| Non-smoker | –0.9 (–1.8 to 0.1) | 0.07 | –0.8 (–1.7 to 0.2) | 0.11 | –0.2 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.29 | –0.1 (–0.5 to 0.2) | 0.50 |

SHAI: Short Health Anxiety Inventory.

In the total SHAI scores, the third-year students had an average of 2 points less than the second-years (p = 0.01); the fourth-years 1.6 points less than the second-years (p = 0.03); the fifth-years 5.2 points less than the second-years (p < 0.001); and the sixth-years 3 points less than the second-years (p = 0.001). In addition, it was found that non-smokers had an average of 2.3 points less than occasional smokers (p = 0.002) (information not shown in the tables) (Table 3).

On the main section of the SHAI, third-year students had an average of 1.7 points less than second-year students (p = 0.01); the fourth-years 1.5 points less than the second-years (p = 0.01); the fifth-years 4.3 points less than the second-years (p < 0.001), and the sixth-years 2.9 points less than the second-years (p < 0.001). In addition, it was found that non-smokers had an average of 1.8 points less than occasional smokers (p = 0.003) (information not shown in the tables) (Table 4).

In the negative consequences section of the SHAI, it was found that fifth-year students had an average of 0.9 points less than second-year students (p = 0.002). In addition, a significant difference was found between being an occasional smoker and being a non-smoker. Non-smokers had an average of 0.5 points less than occasional smokers (p = 0.04) (information not shown in the tables) (Table 4).

DiscussionMain findingsThe median of HA measured by the SHAI was 13 points, with a mean of 14. HA at levels compatible with hypochondriasis affected 4.41% of the population.

This study reports an association between HA measured through the SHAI and the year of studies; the second year shows the highest scores in both the main section and the negative consequences section. In addition, it highlights the association between HA and smoking, with higher values in occasional smokers, as well as a weak negative correlation with age. No association was found with gender, place of birth, or having a first-degree relative doctor or first-degree relative healthcare worker.

Comparison with other studiesA systematic review of the SHAI reported average HA of 12.4 ± 6.8 points in the non-clinical population and 32.5 ± 9.6 in the hypochondriac population.5 In another later study carried out on Spanish adolescents,27 a mean HA level of 10.5 ± 5.7 points was reported. In studies carried out on university Psychology students, the averages recorded ranged from 10.8 ± 6.4 in students in the United States6 to 13.4 ± 5.3 points in Canadian students.9 This data is comparable to our study’s data, where we had an average of 14.0 ± 6.7 points. This suggests the average level of HA varies according to the population studied, and is higher in students of Psychology and Medicine than in the general population, and higher in students of Medicine than those of Psychology. This difference in the averages is probably due to the fact that medical students start perceiving symptoms as medical signs when they learn about new illnesses, a phenomenon considered to be a form of transient hypochondriasis.14

In the general population, no gender differences are reported.10 Studies carried out on university students in the United States29 and an English occupational sample30 also reported no gender differences in HA, in line with our study. However, a study in Spanish adolescents27 found that females had higher levels of HA than males, a finding similar to that reported in another study on patients with anxiety disorders.31 This may be based on the theory that women are more likely to have an anxiety disorder than men.32 The greater susceptibility of females to stress-related neuropsychiatric diseases is due to hyperactivity of the extrahypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor circuits, which doubles the chances of having an anxiety disorder.33 We would therefore have expected to find gender differences in our study. However, that was not the case.

Regarding the association between HA and the year of studies, specifically concerning second-year Medicine, where the highest levels of HA were reported, a study in Medical Students in Pakistan found that second-year students had the highest HA levels and fifth-years, the lowest.12 This was in line with our results, although their differences were not significant (p > 0.05). It has also been reported that, because of the curriculum, students have subjects like pathophysiology and pathology at intermediate levels, providing them with information about the many diseases, and this can be a trigger factor for them to suffer greater concerns about their health at that point in their academic training.34 Therefore, having not yet reached the field of pre-professional practice, their HA levels increase, as the most common diseases tend not to be the most serious, which are the main concern of students.34 However, in our study, HA levels were lower on average in the more advanced years and higher in the less advanced years, despite having courses like pathology between third and fourth year without having reached the field of pre-professional practice.

The theory has been proposed in the literature that people smoke to relieve psychiatric symptoms.35,36 As far as HA and smoking is concerned, the above association was reaffirmed in an Australian study suggesting that current smokers have twice the level of HA as people who have never smoked.10 In our study, occasional smokers scored an average of 2.3 points higher for HA than non-smokers. It therefore seems that there are differences in HA levels determined by smoking, although the association is not reported as significant with all categories of smokers. We should point out that there is an alternative hypothesis that long-term smoking increases susceptibility to disorders such as anxiety and depression.37,38 One systematic review reported general disagreement on whether smoking leads to anxiety, anxiety leads to smoking or increases smoking behaviour, or the relationship is two-way.39 Based on the above, there is an obvious need for further study into smoking and HA, analysing which comes first, the various categories of smoker and other variables involved, to obtain more consistent results in this area.

The importance of preventing the consequences of HA needs to be underlined. If not diagnosed or adequately treated with cognitive-behavioural therapy, it can lead to serious repercussions.21,22 The average of the hypochondriac population is well above the average obtained by all other populations,5,27 including the medical students assessed in this study. The population with the actual diagnosis is the only group with an average above the cut-off point compatible with hypochondriasis.5 This group will definitely require timely and appropriate follow-up and treatment by a specialist. However, that does not mean that other studied populations reporting high levels compared to the general population, as in this study, do not require timely follow-up, simply that, with the average values obtained, their risk of suffering the negative consequences of hypochondriasis should not be much higher than the general population.23,26 We believe that all those with values at or above the cut-off point should be identified, as with the 4.41% of our population that scored ≥27, and provided with all the necessary measures for adequate diagnosis and treatment.

Limitations and strengthsBecause the questionnaire is self-administered, we need to consider the possibility of a social desirability bias. To try to make the information as reliable as possible, we stressed that there was no wrong answer and that the information would be treated anonymously. The tool used to measure health anxiety, the SHAI, is adapted for the Colombian population, which means there could be terms that make it difficult to fully understand. However, the instrument was carefully reviewed before use and was found to be understandable and applicable to the study population. We carried out an exploratory factor analysis with the basis obtained, and the internal consistency was evaluated, with good results. To estimate reliability, Cronbach’s alpha index was calculated, with a total scale reliability of 0.85; with 0.83 and 0.72 for the main section and the negative consequences section respectively.

We should point out that this study, unlike others, did not include the suffering of any non-psychiatric illness by the students themselves or a close relative among its variables, so information on the association of HA with these variables could have been lost. Personal history of a psychiatric disorder or illness is another variable that would be relevant to consider, but it was not included in this study due to a possible overlap with HA.

It is important to emphasise that the SHAI was used to assess HA in the respondents. No diagnosis was made and the results were not a substitute for a medical consultation; and we kept this at the forefront throughout the investigation.

The strengths of the study include the fact that the information is novel, as this is the first study to analyse HA in students at a Peruvian university, and one of the few to have been carried out in Latin America.

ConclusionsAs there is not much information about HA in either Peru or Latin America as a whole, we recommended that more studies should be carried to increase our knowledge in this area. Given the problems it can cause, this is a health issue that needs to be given its due importance. We believe we should look for other possible phenomena to help us better understand the origin of this health problem and study them longitudinally, as it would be easier to analyse the transient nature of the association between these factors and HA and obtain better evidence.

This study shows that age, year of studies and smoking are associated with HA in medical students at a private university in Peru. The average HA score was 14, with no differences in terms of gender, place of birth, or having a first-degree relative doctor or a first-degree relative healthcare worker. In light of these results, we would urge HA to undergo further assessment and analysis, given its importance and limited evidence in this area. We presume there are other factors associated with HA, and these need to be studied to implement positive, effective interventions supported by the best possible evidence.

Conflicts of interestThe article is based on an academic thesis entitled “Factors associated with health anxiety in medical students at a private university in Lima, Peru”, 2020, prepared by the authors RRM and AA, presented at the Universidad Peruana de Ciencias Aplicadas [Peruvian University of Applied Sciences].

Please cite this article as: Robles-Mariños R, Angeles AI, Alvarado GF. Factores asociados con la ansiedad por la salud en estudiantes de Medicina de una Universidad privada en Lima, Perú. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:89–98.