The consequences of homophobia can affect the integrity, mental and physical health of homosexual individuals in society. There are few studies in Peru that have evaluated homophobia in the medical student population.

ObjectiveTo establish the social, educational and cultural factors associated with homophobia among Peruvian medical students.

MethodsA cross-sectional analytical study was conducted in 12 medicine schools in Peru. Homophobia was defined according to a validated test, which was associated with other variables. Statistical associations were identified.

ResultsThe lowest percentages of homophobic students (15–20%) were found in the four universities in Lima, while universities in the interior of the country had the highest percentages (22–62%). Performing a multivariate analysis, we found that the frequency of homophobia was lower for the following variables: the female gender (PRa=0.74; 95% CI, 0.61–0.92; p=0.005), studying at a university in Lima (PRa=0.57; 95% CI, 0.43–0.75; p < 0.001), professing the Catholic religion (PRa=0.53; 95% CI, 0.37–0.76; p < 0.001), knowing a homosexual (PRa=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60–0.90; p=0.003) and having treated a homosexual patient (PRa=0.76; 95% CI, 0.59–0.98; p=0.036). In contrast, the frequency of homophobia increased in male chauvinists (PRa=1.37; 95% CI, 1.09–1.72; p=0.007), adjusted by four variables.

ConclusionsHomophobia was less common in women, in those who study in the capital, those who profess Catholicism and those who know/have treated a homosexual. In contrast, male chauvinists were more homophobic.

Las consecuencias de la homofobia pueden afectar a la integridad y la salud mental y física de los individuos homosexuales en la sociedad. En Perú hay escasos estudios que hayan evaluado la homofobia en la población médico-estudiantil.

ObjetivoDeterminar los factores sociales, educativos y culturales asociados con la homofobia entre estudiantes de Medicina peruanos.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de tipo transversal analítico en 12 sedes de Medicina humana peruanas. Se definió homofobia según un test validado, que se asoció con otras variables. Se obtuvieron estadísticos de asociación.

ResultadosLas 4 universidades de Lima obtuvieron menores porcentajes de alumnos homofóbicos (15–20%) que las universidades del interior del país (22–62%). Al realizar el análisis multivariable, disminuyeron la frecuencia de homofobia: ser mujer (RPa=0,74; IC95%, 0,61-0,92; p=0,005), estudiar en una universidad de Lima (RPa=0,57; IC95%, 0,43-0,75; p < 0,001), profesar la religión católica (RPa=0,53; IC95%, 0,37-0,76; p < 0,001), conocer a un homosexual (RPa=0,73; IC95%, 0,60-0,90; p=0,003) y haber atendido a un paciente homosexual (RPa=0,76; IC95%, 0,59-0,98; p=0,036); en cambio, ser machista aumentó la frecuencia de homofobia (RPa=1,37; IC95%, 1,09-1,72; p=0,007), ajustado por 4 variables.

ConclusionesLa homofobia fue menos frecuente entre las mujeres, los que estudiaban en la capital, los que profesan el catolicismo y los que conocen/han atendido a un homosexual; por el contrario, los machistas fueron más homofóbicos.

Today, homophobia is no longer considered to be a pathological disorder. The World Health Organisation (WHO) removed homosexuality from the list of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10),1 as well as from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).2 As such, homosexuality is now considered to be an alternative lifestyle, which occurs as a variant of human sexuality.2 However, society still shows negative attitudes towards homosexuality, despite the current legal regulations,3 possibly due to the cultural4 and religious5 factors characteristic of each community.

Homophobia is defined as aversion towards homosexuality or homosexual people,6 and some authors consider it a type of discrimination.4 This type of activity against the homosexual community hinders their access to health services,7 impacts their emotional and mental health8 and increases their susceptibility to being victims of physical violence,9 which in many cases leads to suicide.10

The homophobic attitude that some healthcare professionals adopt goes against the International Code of Medical Ethics, which stipulates that all physicians must respect the rights of the patient, irrespective of any type of ideology, sexual preference or other characteristics.11 Studies have been carried out which evaluate the attitudes of physicians with regard to homosexuality, revealing homophobic attitudes in up to 10% of the population.12–14 It is highly likely that many of these attitudes have been developed during their undergraduate training, as highlighted by some studies.15–17

The Latin American culture, and particularly the Peruvian culture, tends to be very conservative with certain topics,18,19 including homosexuality.20–22 Although the major demographic change which drove the modernisation process meant that many expectations on social roles were redefined,23 the role of homosexuals and their image with regard to society has not undergone major changes.24 There are limited studies on homophobia in the medical-student population,25 particularly in conservative cultures such as found in Peru. As such, the objective of our study was to determine the frequency and the factors associated with homophobia in Peruvian medical students.

MethodsStudy design and populationAn analytical cross-sectional study was conducted, with prospective data collection. The study population was made up of students from 11 Peruvian medical schools spread over 12 campuses, as one of the universities has two campuses. The following medical schools were included: Universidad de San Martín de Porres [San Martín de Porres University] (USMP), Universidad Nacional de Piura [Piura National University] (UNP), Universidad Nacional de San Cristóbal de Huamanga [San Cristóbal de Huamanga National University] (UNSCH), Universidad Nacional del Centro de Perú [National University of Central Peru] (UNCP), Universidad Nacional Hemilio Valdizán [Hemilio Valdizán National University] (UNHEVAL), Universidad Nacional José Faustino Sánchez Carrión [José Faustino Sánchez Carrión National University] (UNJFSC), Universidad Nacional Pedro Ruiz Gallo [Pedro Ruiz Gallo National University] (UNPRG), Universidad Nacional San Luis Gonzaga de Ica [San Luis Gonzaga National University of Ica] (UNICA), Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia [Cayetano Heredia Peruvian University] (UPCH), Universidad Peruana Los Andes [Los Andes Peruvian University] (UPLA), Universidad Ricardo Palma [Ricardo Palma University] (URP). The Universidad de San Martín de Porres has two campuses, one in the city of Lima and another in the city of Chiclayo.

Sample and samplingProbability sampling was carried out; the sample size was found from the comparison of two means of the homophobia scale according to having a homosexual friend: 44.94 and 38.42, respectively.26

A percentage error of 5% and a statistical power of 99% was assumed, which gave a sample size of 198 students for each school in the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe medical students who were enrolled in the first semester of 2016 at the above medical schools and who were in the first to sixth years of the degree and who gave their verbal consent (applied digitally prior to the survey) were included in the study. Participants who did not respond to the main variables of the survey and who did not belong to a Peruvian university were excluded (19 surveys excluded for these reasons).

Measurement of homophobia and other variablesThe Homophobia Scale (HS-7) was used to measure the level of homophobia. The Spanish version of this scale was validated in a previous study, in which it was found that it has good reliability and validity in a population of Colombian medical students, with an internal consistency of 0.78, acceptable convergent, divergent and construct validity, with a single factor which explains 45% of the variance.27

The level of religiousness, in the case of Christians, was measured using the Francis-5 scale, a five-item questionnaire which measures attitude with regard to prayer, Jesus and God. The five questions have Likert-type responses with five response options (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) with scores from 0 to 4 per item. The total score ranges from 0 to 20, and a higher score indicates a higher level of religiousness. The scale was validated in a population of adolescents. The factor analysis showed a KMO coefficient of 0.89, in addition to a one-dimensional structure, with a single factor that explained 73.6% of the variance, which gives it good validity, in addition to a Cronbach's alpha and McDonald's coefficient omega of 0.91, which gives it good reliability.28

The male chauvinism variable was evaluated with the Sexual Male Chauvinism scale, developed by Díaz Rodríguez et al., which has one factor which explains 98% of the variance in the confirmatory factor analysis and α=0.91. The test has 12 questions with a Likert-type scale, which range from 1 to 5 (from strongly disagree to strongly agree).29

Other sociodemographic, educational and social variables were also collected, such as: gender (female or male), age (in years), department of origin of the university (Lima metropolitan area or province), type of university where they study (private or public), year of study, clinical courses (yes I am taking courses or I am not taking courses), type of religion that they practise (Catholic or non-Catholic), male chauvinism score according to the test (quantitative value of the test), any homosexual acquaintance (yes, I have a homosexual acquaintance or no, I do not have one) and if they have had contact with any homosexual patients in their hospital practice (yes, I have had contact or no, I have not had contact).

ProceduresThe list of students from first to sixth year of the medical schools mentioned was compiled. Subsequently, random sampling was performed and data collection was started in July 2016. Each collector communicated with each one of the participants via telephone calls or by virtual means (email and Facebook).

The survey was carried out using the virtual platform Google Docs and it was sent to each participant by email as part of the confidentiality strategy protecting the participants and their responses. The data obtained up to 31 December 2016 were analysed and imported into a database in Microsoft Excel 2010 table format.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was carried out using the program Stata v.11.1 and involved an indiscriminate exploratory analysis due to the fact that no prior hypothesis had been established. For the descriptive analysis, the absolute and relative frequencies of the categorical variables obtained were determined. Furthermore, the median [interquartile range] and the mean±standard deviation of the quantitative variables obtained were calculated according to the Shapiro–Wilk normality test of the numerical data.

For the inferential analysis, a 95% confidence interval was assumed. In bivariate statistics, p-values and the crude prevalence ratios (PR) with their respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were obtained, using generalised linear models, with the Poisson family plus the log link function, robust models and using the university campus as a cluster adjustment. With the same assumptions, the multivariate statistical analysis was performed to obtain adjusted prevalence ratios (PRa). For this section, a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerationsPrior to being carried out, this study was sent to the Independent Ethics Committee of the Hospital Nacional Docente Madre-Niño [Mother and Child National Teaching Hospital] (HONADOMANI) (RCEI-40), which approved it. For the use of student lists from the first to sixth year of the universities, authorisation was requested from the corresponding medical school.

As it was a virtual survey, each participant was asked for his/her informed consent verbally, and he/she was also informed of the objectives and aims of the study. The survey did not include variables that infringed upon the anonymity of the participants.

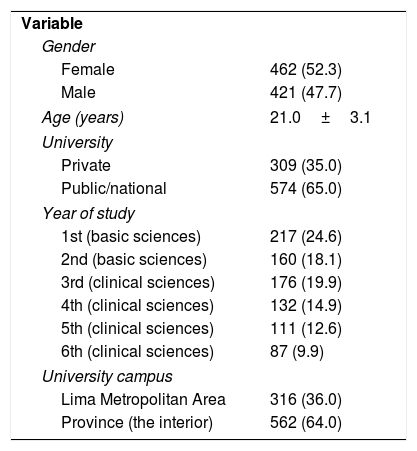

ResultsOf the 883 individuals surveyed, 52.3% (462) were female; the mean age was 21±3.1 years; the majority studied at public/national universities (65.0%), were studying the first year of Medicine (24.6%) and their university was located in the interior of the country (64.0%). The other descriptive values are shown in Table 1.

Socio-educational characteristics of medical students from eleven Peruvian universities.

| Variable | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 462 (52.3) |

| Male | 421 (47.7) |

| Age (years) | 21.0±3.1 |

| University | |

| Private | 309 (35.0) |

| Public/national | 574 (65.0) |

| Year of study | |

| 1st (basic sciences) | 217 (24.6) |

| 2nd (basic sciences) | 160 (18.1) |

| 3rd (clinical sciences) | 176 (19.9) |

| 4th (clinical sciences) | 132 (14.9) |

| 5th (clinical sciences) | 111 (12.6) |

| 6th (clinical sciences) | 87 (9.9) |

| University campus | |

| Lima Metropolitan Area | 316 (36.0) |

| Province (the interior) | 562 (64.0) |

Values are expressed as the n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

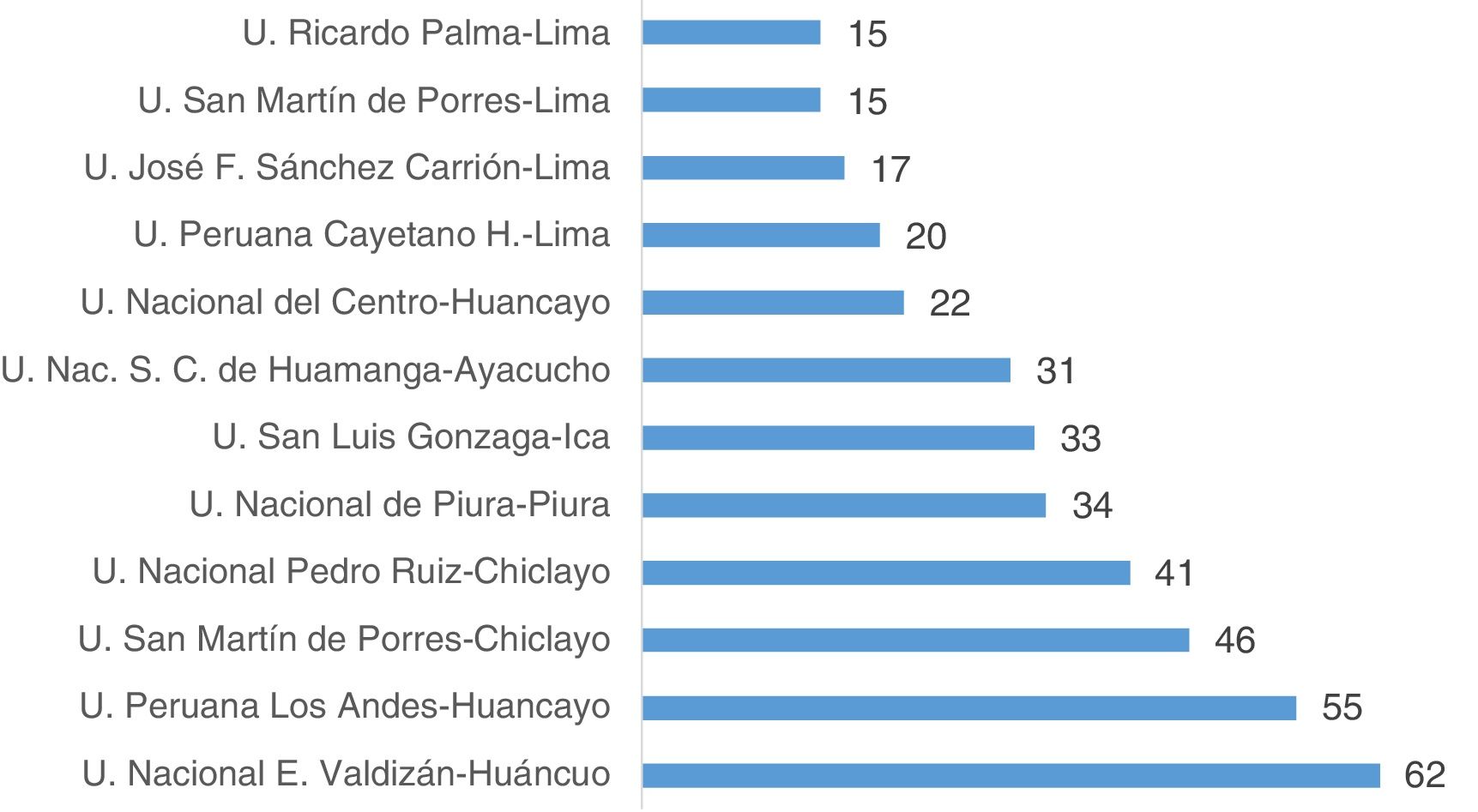

Once the percentage of homophobes from each university had been obtained, it was found that the four universities in Lima had the lowest percentages of homophobic students (15–20%), while the universities in the interior of the country had the highest percentages (22–62%) (Fig. 1).

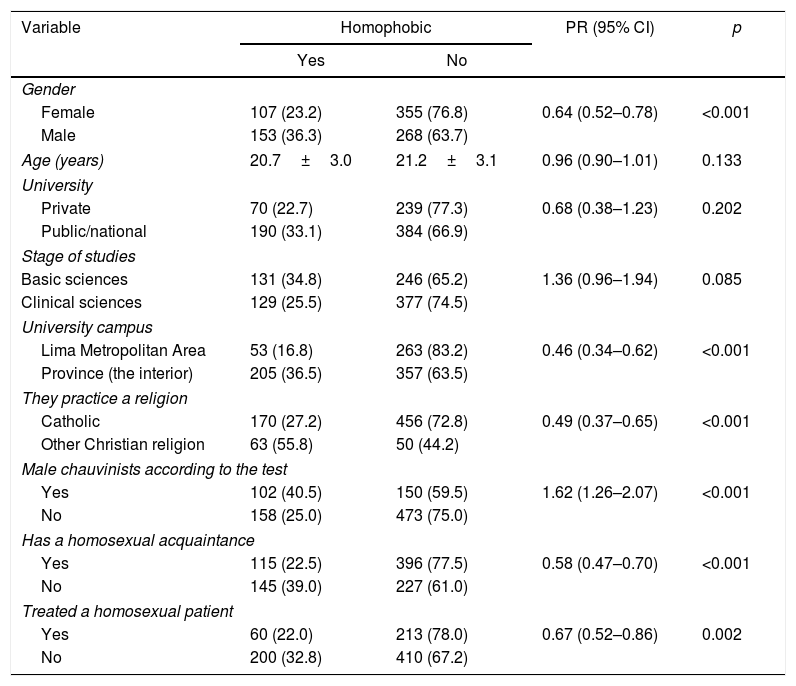

When conducting the bivariate analysis, the following were found to be associated with being homophobic: gender (p<0.001); location of the university of study (p<0.001); type of religion practised (p<0.001); being a male chauvinist (p<0.001); having a homosexual acquaintance (p<0.001) and having treated a homosexual patient (p=0.002) (Table 2).

Bivariate analysis of homophobia according to social, educational and cultural factors among Peruvian medical students.

| Variable | Homophobic | PR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 107 (23.2) | 355 (76.8) | 0.64 (0.52–0.78) | <0.001 |

| Male | 153 (36.3) | 268 (63.7) | ||

| Age (years) | 20.7±3.0 | 21.2±3.1 | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 0.133 |

| University | ||||

| Private | 70 (22.7) | 239 (77.3) | 0.68 (0.38–1.23) | 0.202 |

| Public/national | 190 (33.1) | 384 (66.9) | ||

| Stage of studies | ||||

| Basic sciences | 131 (34.8) | 246 (65.2) | 1.36 (0.96–1.94) | 0.085 |

| Clinical sciences | 129 (25.5) | 377 (74.5) | ||

| University campus | ||||

| Lima Metropolitan Area | 53 (16.8) | 263 (83.2) | 0.46 (0.34–0.62) | <0.001 |

| Province (the interior) | 205 (36.5) | 357 (63.5) | ||

| They practice a religion | ||||

| Catholic | 170 (27.2) | 456 (72.8) | 0.49 (0.37–0.65) | <0.001 |

| Other Christian religion | 63 (55.8) | 50 (44.2) | ||

| Male chauvinists according to the test | ||||

| Yes | 102 (40.5) | 150 (59.5) | 1.62 (1.26–2.07) | <0.001 |

| No | 158 (25.0) | 473 (75.0) | ||

| Has a homosexual acquaintance | ||||

| Yes | 115 (22.5) | 396 (77.5) | 0.58 (0.47–0.70) | <0.001 |

| No | 145 (39.0) | 227 (61.0) | ||

| Treated a homosexual patient | ||||

| Yes | 60 (22.0) | 213 (78.0) | 0.67 (0.52–0.86) | 0.002 |

| No | 200 (32.8) | 410 (67.2) | ||

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PR: crude prevalence ratio.

p-values obtained with generalised linear models, with Poisson family, log link function, robust models and using the university campus as the cluster adjustment.

Values are expressed as the n (%) or mean±standard deviation.

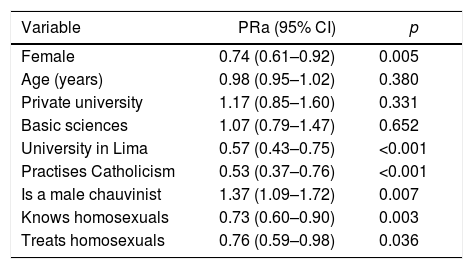

In the multivariate analysis, the frequency of homophobia reduced with the following factors: being female (PRa=0.74; 95% CI, 0.61–0.92; p=0.005); studying in a university in Lima (PRa=0.57; 95% CI, 0.43–0.75; p<0.001), practising the Catholic religion (PRa=0.53; 95% CI, 0.37–0.76; p<0.001); knowing a homosexual person (PRa=0.73; 95% CI, 0.60–0.90; p=0.003) and having treated a homosexual patient (PRa=0.76; 95% CI, 0.59–0.98; p=0.036). In contrast, being a male chauvinist increased the frequency of homophobia (PRa=1.37; 95% CI, 1.09–1.72; p=0.007). All these variables were adjusted for age, type of university, current educational stage and educational campus (Table 3).

Multivariate analysis of homophobia according to social, educational and cultural factors among Peruvian medical students.

| Variable | PRa (95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 0.74 (0.61–0.92) | 0.005 |

| Age (years) | 0.98 (0.95–1.02) | 0.380 |

| Private university | 1.17 (0.85–1.60) | 0.331 |

| Basic sciences | 1.07 (0.79–1.47) | 0.652 |

| University in Lima | 0.57 (0.43–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Practises Catholicism | 0.53 (0.37–0.76) | <0.001 |

| Is a male chauvinist | 1.37 (1.09–1.72) | 0.007 |

| Knows homosexuals | 0.73 (0.60–0.90) | 0.003 |

| Treats homosexuals | 0.76 (0.59–0.98) | 0.036 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; PRa: adjusted prevalence ratio.

The prevalence of homophobia, using the upper tertile of the seven-item Homophobia Scale, was around 35%. This prevalence is higher than that of other similar studies in a population of medical students, which place it between 10% and 25%.30,31 However, this difference may be due to the large quantity of methods and scales used to measure homophobia; the scale used in this study does not have a pre-established cut-off point but it has been validated in a population of social and cultural characteristics similar cultures to ours, where 17.3±5.4 points were obtained, only a little more than half a point more than ours. It could therefore be said that the results are very similar.27

The condition of being homophobic, probably shared to the same extent with other Latin American student populations, is significant, as the attitudes that these students have of these types of patient when they are physicians may significantly undermine the doctor-patient relationship that they establish,32 in which there could be stigmatisation due to the association with the HIV epidemic.14,33 This means that in the medical consultation many of the patients omit important information about their sexual activity with others of the same gender, losing the opportunity to discuss safer sex interventions and control of the transmission of high-risk diseases.34 In addition, the prejudices that healthcare personnel may have may affect their willingness to give this type of guidance to homosexual people.35 Similarly, it is important to recognise that homophobic attitudes may affect the well-being of homosexual medical students who have not made their sexual orientation public. This could trigger an emotional burden that hinders their academic development and their proper training as physicians, and, if they have made it public, they may suffer coercion and even abandon the degree.30

According to the results obtained in the study, homophobia was more prevalent among the male population than the female population, something which was also found in most studies evaluating this problem.36–38 This is highly likely to be a result of the sociocultural influence of the conservative culture in which we live and which governs the formation of social roles according to gender. This negative attitude of the male population may also be related to the type of routine upbringing, which delves into a greater aversion to signs of femininity in males, such as signs of weakness or of failure in the construction of their role as male in society.39,40

It was also found that percentages of homophobia were higher among students from the medical schools of the provincial universities. This is possibly due to the conservative and traditional characteristics of the population that lives in the interior departments of Peru,41,42 which leads the social environment to inform less on controversial topics such as homosexuality.43 However, some studies did not find a statistical difference between the percentages of homophobic behaviour of provincial universities and those in the capital.44 This may be due to factors regarding the study population, such as conducting the study in countries with an equal or greater development index, mainly in educational and economic sectors, or it could also be influenced to a certain extent by the high rate of rejection, which could have altered the final results.

According to the Francis-5 scale, students with a higher degree of religiousness have a higher degree of homophobia. This relationship has been found in a large number of studies on homophobia and is not limited to the population of medical students. Rather, the most conservative societies and those with more negative attitudes with regard to homosexuality tend to be more religious. This plays a significant role in the formation of the morals of individuals, which in many cases shape prejudices against certain groups of people.45–48

Lastly, being a male chauvinist increased the frequency of homophobia. Male chauvinism in Latin American countries such as Peru is very common,49 a result of the social, political, religious and family context individuals are exposed to while they are in the process of growth and development.50 Only one study which claims that male chauvinist attitudes trigger homophobia has been found.51 However, this association could be assumed due to the fact that homosexuality breaks the masculinity scheme of chauvinistic people, who are characterised by rejecting everything that emulates traits of femininity in males.51,52

According to the results, it can be concluded that homophobia among medical students varies from 15% to 62%. The factors that reduced the frequency of homophobia were being female, studying in a university in Lima, practising the Catholic religion, knowing a homosexual person and having treated a homosexual patient. In contrast, being a male chauvinist increased the frequency of homophobia.

LimitationsThe study has two limitations: (a) as it is a cross-sectional study, it is not possible to establish causality of the variables, due to the fact that the temporality of the exposure factors cannot be determined. However, it has been possible to determine the prevalence ratio, which gives an overview on the risk of being homophobic according to the variables analysed, and (b) the study also involves a selection bias, as the rejection rate was >10% in each university selected, which prevents inferences from being made for each study campus (or prevalences). However, it is possible to use the associations found, as the statistical power was calculated for each crossover, which in all cases was >93%. This makes these results the first to reveal the factors which are associated with homophobia in a group of future healthcare professionals, which is important given their upcoming role as members of the health sector.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Nieto-Gutierrez W, Komori-Pariona JK, Sánchez AG, Centeno-Leguía D, Arestegui-Sánchez L, De La Torre-Rojas KM, et al. Factores asociados a la homofobia en estudiantes de Medicina de once universidades peruanas. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2019;48:208–214.