Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) is a condition associated with multiple negative outcomes. People with mental illness might be at increased risk of having it, given that medication given has adverse effects on weight and there are alterations in sleep associated with them; however, there are few studies in this population.

ObjectiveDescribe the patients and the results of polysomnography ordered based on clinical symptoms in a psychiatric outpatient clinic between 2012 and 2014.

MethodsA case series in which medical records were evaluated.

Results58 patients who underwent polysomnography, 89% of them had OSAS, 16% were obese and 19% were been treated with benzodiazepines.

ConclusionsThis is a condition that must be considered during the clinical evaluation of patients with mental illness, since its presence should make clinicians think about drug treatment and follow up.

El síndrome de apnea obstructiva del sueño (SAOS) se asocia a múltiples desenlaces negativos. Se ha propuesto que las personas con enfermedad mental están en mayor riesgo, en parte por sobrepeso y por las alteraciones del sueño asociadas con algunos medicamentos. Sin embargo, son pocos los estudios en esta población.

ObjetivoDescribir a la población y el resultado de las polisomnografías solicitadas ante sospecha clínica en pacientes de consulta externa de una clínica psiquiátrica.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo de una muestra de pacientes consecutivos atendidos entre 2012 y 2014.

ResultadosDe los 58 pacientes de los que se solicitó polisomnografía, 52 (89%) presentaban SAOS. De estos, el 16% cursaba con obesidad y el 19% tomaba benzodiacepinas.

ConclusionesEsta es una enfermedad que se debe tener en cuenta durante la evaluación clínica de los pacientes con enfermedad mental, dado que su presencia implica precaución al plantear el tratamiento farmacológico y hacer el seguimiento.

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS) is classified as a “breathing-related sleep disorder” and is characterised by repetitive closure of the upper airway during sleep, with decreased arterial oxygen saturation. The standard diagnostic method is polysomnography, and severity is classified according to the number of apnoea and hypopnoea events per hour. This disorder is mild if there are between 5 and 15 events plus some symptoms (such as excessive sleepiness, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, insomnia, difficulty breathing at night, choking sensation during the night, breathing interruptions or loud snoring); moderate if there are more than 15 but less than 30, and severe when there are more than 30 events/h.1

OSAS is a highly prevalent disorder that is estimated to affect between 4% and 8% of adults, and has significant negative repercussions on quality of life and considerable associated morbidity and mortality.2–4 Although OSAS was defined in the 1970s, its negative impact on mortality and quality of life was only documented some 20 years ago. OSAS patients are at greater risk of hypertension, insulin resistance, diabetes mellitus, coronary events, cerebrovascular events, cognitive alterations, perioperative complications, in-hospital mortality and all-cause mortality, as well as occupational and traffic accidents.5–7 This is why it is so important to make the initial diagnosis and start treatment. Risk factors for OSAS include obesity, male gender, aged over 50, family history, nasal obstruction, use of alcohol or sedatives, cigarette smoking, gastro-oesophageal reflux, hypothyroidism and acromegaly, among others.8,9

Few studies have been published on the association between OSAS and the development, prognosis and impact of mental illness. It has been suggested that individuals with mental illness may be at increased risk of suffering from OSAS due to weight gain caused by most antipsychotics and mood stabilisers, the presence of respiratory events related to the use of sedative drugs, and a less healthy lifestyle.10–14 A search of PubMed using the MeSH terms “Depressive Disorder, Major” and “Sleep Apnoea, Obstructive” retrieved 18 articles, one of which found that, according to a study of a database of over 2 million obese individuals, OSAS patients are at increased risk of depression (odds ratio [OR]=1.85; confidence interval [CI], 1.80–1.88; p<0.001).15 Another study evaluated 53 people with coronary heart disease, and found a similar prevalence of depression in patients with and without OSAS.16 However, the small sample size prevented the authors from drawing definitive conclusions. A more recent systematic review found that up to 69% of individuals with bipolar affective disorder presented OSAS, albeit in studies with a high risk of selection bias.17 A systematic review of the literature on people with major mental illness found a prevalence of 36.3% for OSAS in people with major depressive disorder, 24.5% in patients with bipolar affective disorder and 15.4% in patients with schizophrenia. However, a review of the articles included showed that some had requested polysomnography due to suspicion of OSAS, such as medication-induced symptoms of daytime sleepiness, and this may have distorted the true prevalence.18 Furthermore, a study in older people found that apnoea–hypopnoea is associated with poor cognitive functioning and increased risk of dementia.19,20

The aim of this study is to describe the general characteristics and polysomnographic parameters of a sample of psychiatric patients seen on an outpatient basis in a psychiatric clinic.

Material and methodsThis is a descriptive study of a series of consecutive patients undergoing polysomnography for clinical suspicion of OSAS in a psychiatric clinic. The outpatient department of the clinic attends approximately 5000 adult patients per month, whose health insurance mainly covers individuals living in the city of Bogotá. Data from the medical history of patients seen in a psychiatry outpatient clinic between 2012 and 2014 were collected. The information obtained from the medical records was organised and summarised in a Microsoft® Excel® 2013 spreadsheet, which also calculated the summary measures of the findings using measures of central tendency and dispersion. The study was approved by the institution's ethics committee and is classified as risk-free research, since data were taken from the medical history and no intervention or data collection was performed.21

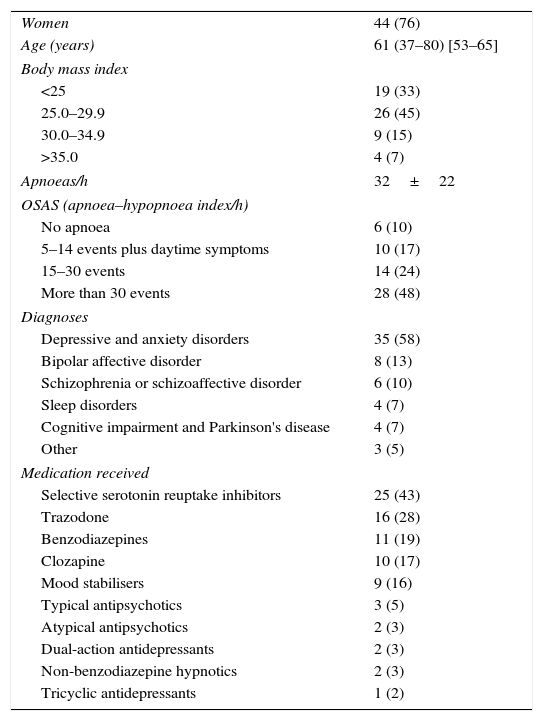

ResultsTable 1 shows the general characteristics of the study sample formed of 58 adults, mostly female, half of whom were overweight. The median Epworth Sleepiness Scale score was 7 (0–24) points, and 52 patients (89%) met OSAS diagnostic criteria. The patients were diagnosed with a variety of disorders, some patients with more than one diagnosis; 16 (28%) received 1 medication, 25 (43%) received 2, 12 (20%) received none, and the other 5 (9%) received 3 or more. The antidepressants prescribed were, in order of frequency: fluoxetine, sertraline, escitalopram, duloxetine, mirtazapine, amitriptyline and trazodone; the benzodiazepines lorazepam, clonazepam and alprazolam, the mood stabilisers lithium carbonate and valproic acid, the typical antipsychotics haloperidol, levomepromazine and pipotiazine, the atypical antipsychotics risperidone, aripiprazole and clozapine and the non-benzodiazepine hypnotic zolpidem.

General characteristics of patients (n=58).

| Women | 44 (76) |

| Age (years) | 61 (37–80) [53–65] |

| Body mass index | |

| <25 | 19 (33) |

| 25.0–29.9 | 26 (45) |

| 30.0–34.9 | 9 (15) |

| >35.0 | 4 (7) |

| Apnoeas/h | 32±22 |

| OSAS (apnoea–hypopnoea index/h) | |

| No apnoea | 6 (10) |

| 5–14 events plus daytime symptoms | 10 (17) |

| 15–30 events | 14 (24) |

| More than 30 events | 28 (48) |

| Diagnoses | |

| Depressive and anxiety disorders | 35 (58) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 8 (13) |

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 6 (10) |

| Sleep disorders | 4 (7) |

| Cognitive impairment and Parkinson's disease | 4 (7) |

| Other | 3 (5) |

| Medication received | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 25 (43) |

| Trazodone | 16 (28) |

| Benzodiazepines | 11 (19) |

| Clozapine | 10 (17) |

| Mood stabilisers | 9 (16) |

| Typical antipsychotics | 3 (5) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 2 (3) |

| Dual-action antidepressants | 2 (3) |

| Non-benzodiazepine hypnotics | 2 (3) |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | 1 (2) |

The values are expressed as n (%) or median (range) [interquartile range].

This study is a preliminary evaluation of the importance of recognising OSAS in patients with mental illness in Colombia. Due to the sampling strategy used, we were unable to calculate the prevalence of this condition, since polysomnography was ordered for the clinical suspicion of sleep disorder, and therefore our sample is not representative of the population with mental illness. Despite these limitations, it is interesting to observe that 89% of patients undergoing polysomnography had an apnoea–hypopnoea index of at least 5 events/h associated with daytime symptoms.1 A small proportion (16%) were obese or taking benzodiazepines (19%). These results should be interpreted with caution, since the polysomnography was ordered on the basis of a clinical suspicion of OSAS, and the population studied consisted of overweight elderly women, which is a risk factor for this disorder.6

Few studies have evaluated the prevalence of OSAS in patients with mental illness, and those that have been published have small samples and are based, as in this case, on polysomnography ordered due to clinical suspicion, and for that reason are not representative of individuals with mental illness. One study,22 for example, found an OSAS prevalence of 39% in a population of 51 patients with major depressive disorder, while another,23 reported prevalence of 59% in individuals with major depressive disorder or bipolar affective disorder. The only study comparing patients with various diagnoses10 found a prevalence of OSAS of 46% in men and 58% in women with schizophrenia, 20% of men and 3% of women with major depressive disorder, and 27% of men and 15% of women with bipolar affective disorder referred to polysomnography on suspicion of OSAS. Finally, another study24 found that 21% of patients with bipolar affective disorder were referred to polysomnography on clinical suspicion.

ConclusionsOSAS must be taken into account during the clinical evaluation of patients with mental illness. In the presence of this disorder, caution must be taken when prescribing pharmacological treatment and undertaking follow-up. Few studies of this disorder in patients with mental illness have been published, but the findings suggest that the prevalence is higher than that reported in the general population.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

FundingThis study did not receive any funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Tamayo Martínez N, Rosselli Cock D. Síndrome de apnea obstructiva del sueño en personas atendidas en consulta externa de psiquiatría: serie de casos. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2017;46:243–246.