To determine the prevalence of burnout syndrome and the associated variables in medical specialists in Mexico.

MethodsObservational, descriptive and cross-sectional study, by means of a census of 540 medical specialists from three Regional Hospitals. Using their identification card and self-administered Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services questionnaire, descriptive statistics and inferential analysis were performed using SPSS 15.0 and Epi-infoV6.1.

ResultsThere was a 90.0% response in the specialists studied. Burnout was detected in 45.9%. There were significant differences in variables: being female; under 40 years of age; without a stable partner, and less than 15 years together; a working couple; childless; clinical specialty; less than 10 years of professional and current employment, and accumulated work day. A negative correlation was found in burnout with emotional exhaustion, and with depersonalisation. It was positive with a lack of personal fulfilment at work.

ConclusionsBurnout is common (45.9%) in specialist physicians. The average levels of the subscales are close to normal. Emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation behave inversely proportional to the total score of the syndrome, and directly proportional to the lack of personal fulfilment in the work with burnout.

Determinar la prevalencia del síndrome de agotamiento profesional (burnout) y las variables asociadas en médicos especialistas.

MétodosEstudio observacional, descriptivo y transversal, mediante censo de médicos especialistas de 3 hospitales regionales (n = 540), ficha de identificación y Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey autoaplicado. Se realizaron estadísticas descriptivas y el análisis inferencial con SPSS 15.0 y Epi-infoV6.1.

ResultadosUn 90,0% de los especialistas estudiados respondieron. Se detectó burnout en el 45,9%. Hubo diferencias significativas en las variables: ser mujer; la edad < 40 años; no tener pareja estable o llevar menos de 15 años con ella; que la pareja trabaje; no tener hijos; especialidad clínica; menos de 10 años de antigüedad profesional y en el puesto actual de trabajo, y laborar jornada acumulada. Correlación negativa: burnout con agotamiento emocional y con despersonalización. Positiva con la falta de realización personal en el trabajo.

ConclusionesEl burnout es frecuente (45,9%) entre los médicos especialistas. Los niveles medios de las subescalas se encuentran cerca de la normalidad. La afección por el agotamiento emocional y la despersonalización se comportan inversamente proporcionales con la puntuación total del síndrome, y directamente proporcionales con la falta de realización personal en el trabajo con burnout.

Hospital medical personnel are exposed to risk factors in the course of their professional practice.1 These include biological risk factors, due to contact with conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency virus (HIV/AIDS), tuberculosis and hepatitis; chemical risk factors, such as neurotoxic, mutagenic, carcinogenic and anaesthetic substances; physical risk factors, such as noise, ionising and non-ionising radiation, and light; ergonomic risk factors, such as long shifts, limited workspaces, certain postures and prolonged standing, and data visualisation screens; and psychosocial risk factors, in relation to workplace organisation, internal interpersonal relationships (colleagues, superiors and subordinates), external interpersonal relationships (patients and suppliers), etc. These create anxiety, depression, stress and so on.1 Members of this health group are many and varied, with a great deal of social importance and influence, and traditionally there has been a high degree of interpersonal commitment. Currently, there is a great deal of interest in the occupational activities of these professionals, their obligations and the risks to which they are exposed. The most common risk factors are psychosocial, given the diversification of their positions in caring for patients on an outpatient basis, hospitalised patients or patients in the accident and emergency department. In addition to this, they are in charge of resident medical personnel, whom they train in theory and practice. Surgical personnel perform all manner of surgeries. In addition, administrative procedures inherent to medical and surgical procedures at hospitals must be done. Moreover, professional ethical responsibilities and potential medical and legal conflicts in the course of their work must not be overlooked.1

Psychosocial risks represent a major phenomenon with considerable visibility and are closely tied to occupational activities. One possible consequence of chronic stress experienced in the occupational context of specialist medical personnel is burnout syndrome (BOS). Its clinical form was first reported in 1974 by Herbert Freudenberger, an American psychiatrist.2 Freudenberger defined BOS as a state of fatigue or frustration caused by dedication to a cause, way of life or relationship that does not yield the expected reinforcement. This term emerged in the 1970s in the United States to refer to the phenomenon of professional overload, or burnout, of service professionals. In that same period, Cristina Maslach3 studied emotional responses among people working with support professionals. In 1977, at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association, she used "burnout syndrome" to describe the phenomenon in professionals working in human services, healthcare and education under difficult conditions and in direct contact with users. This term was then employed by Californian lawyers to describe the gradual process of loss of a sense of responsibility and apathy among work colleagues.

Maslach and Jackson4 studied this syndrome along three dimensions: emotional exhaustion (EE), manifested in gradual loss of energy, tiredness and fatigue; depersonalisation (DP), identified by a negative shift in attitudes and responses towards others marked by irritability; and lack of personal accomplishment (PA) at work, with a negative outlook on oneself and one's job. In 1982, they established a definition that is among those most widely accepted and used by various authors to conduct their studies, describing it as an inappropriate response to chronic emotional stress with the following key traits: emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and a feeling of inadequacy before the tasks one must complete.5 Based on the studies they conducted, they prepared the Maslach Burnout Inventory-Human Services Survey (MBI-HSS), aimed at health professionals.

In 2001, Christina Maslach published a reflection on the past 20 years of research on BOS and concluded that it should be understood as a multidimensional phenomenon.6 It was validated in Mexican professionals by Grajales.7

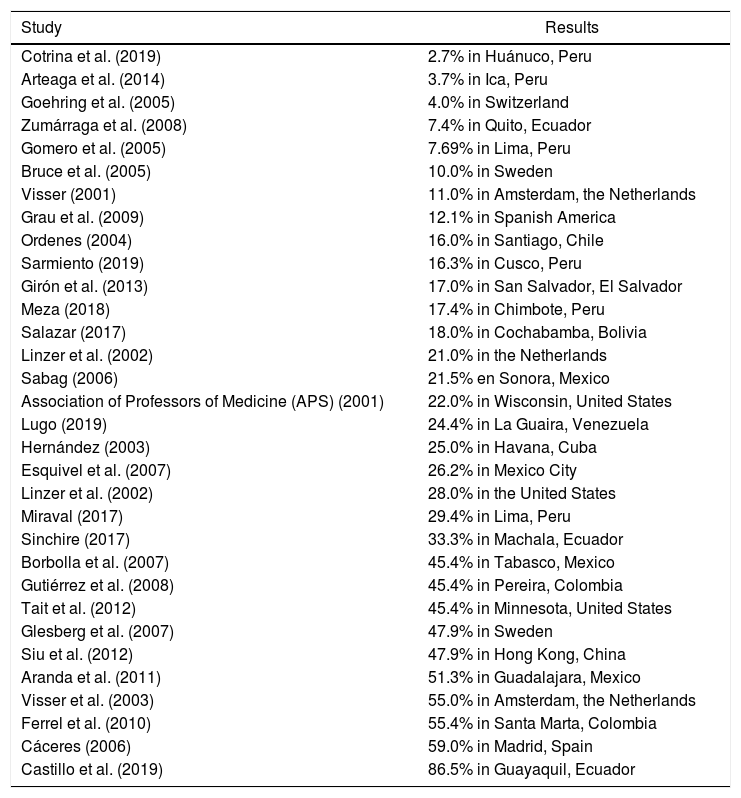

BOS is considered a significant professional risk for specialist physicians, as they are prone to it due to specific aspects of their work, such as high levels of occupational responsibility, legal conflicts, low remuneration, lack of institutional recognition, rates of drug dependence, higher risk of suicide, etc.1 Countries in Europe, the Americas and Asia have found variable prevalences of the syndrome, with reported figures ranging from 2.7%8 to 86.5%.9 For example, the syndrome is detected in Spanish America at a rate of 12.2%, in South America at rates of 2.7%-86.5%, in North America at rates of 22.0%-45.4%, in Europe at rates of 4.0%-55.0%, in Asia at a rate of 47.9%, in Central America and the Caribbean at rates of 17.0%-25.0%, and in Mexico at rates of 21.5%-51.3% (Table 1).

Prevalence of burnout syndrome (BOS) among specialist physicians according to various authors.

| Study | Results |

|---|---|

| Cotrina et al. (2019) | 2.7% in Huánuco, Peru |

| Arteaga et al. (2014) | 3.7% in Ica, Peru |

| Goehring et al. (2005) | 4.0% in Switzerland |

| Zumárraga et al. (2008) | 7.4% in Quito, Ecuador |

| Gomero et al. (2005) | 7.69% in Lima, Peru |

| Bruce et al. (2005) | 10.0% in Sweden |

| Visser (2001) | 11.0% in Amsterdam, the Netherlands |

| Grau et al. (2009) | 12.1% in Spanish America |

| Ordenes (2004) | 16.0% in Santiago, Chile |

| Sarmiento (2019) | 16.3% in Cusco, Peru |

| Girón et al. (2013) | 17.0% in San Salvador, El Salvador |

| Meza (2018) | 17.4% in Chimbote, Peru |

| Salazar (2017) | 18.0% in Cochabamba, Bolivia |

| Linzer et al. (2002) | 21.0% in the Netherlands |

| Sabag (2006) | 21.5% en Sonora, Mexico |

| Association of Professors of Medicine (APS) (2001) | 22.0% in Wisconsin, United States |

| Lugo (2019) | 24.4% in La Guaira, Venezuela |

| Hernández (2003) | 25.0% in Havana, Cuba |

| Esquivel et al. (2007) | 26.2% in Mexico City |

| Linzer et al. (2002) | 28.0% in the United States |

| Miraval (2017) | 29.4% in Lima, Peru |

| Sinchire (2017) | 33.3% in Machala, Ecuador |

| Borbolla et al. (2007) | 45.4% in Tabasco, Mexico |

| Gutiérrez et al. (2008) | 45.4% in Pereira, Colombia |

| Tait et al. (2012) | 45.4% in Minnesota, United States |

| Glesberg et al. (2007) | 47.9% in Sweden |

| Siu et al. (2012) | 47.9% in Hong Kong, China |

| Aranda et al. (2011) | 51.3% in Guadalajara, Mexico |

| Visser et al. (2003) | 55.0% in Amsterdam, the Netherlands |

| Ferrel et al. (2010) | 55.4% in Santa Marta, Colombia |

| Cáceres (2006) | 59.0% in Madrid, Spain |

| Castillo et al. (2019) | 86.5% in Guayaquil, Ecuador |

The knowledge acquired to date has laid the foundations for implementing interventions, supported by techniques and activities to cope with and manage chronic work stress, all in accordance with the level at which the intervention will be carried out: individual, group or institutional. Most programmes focus on training in specific aspects of BOS; others focus on raising awareness among workers of the importance of preventing it. However, current knowledge can aid in structuring policies to benefit healthcare personnel here and now.

Material and methodsThe objective of our study was to contribute specific elements to the study of BOS (prevalence, subscale values and determination of associated variables) in a census sample of three regional hospitals belonging to one of the largest healthcare institutions in Latin America, in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara (MAG), Mexico.

An observational, descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted with the goal of determining the frequency of and variables associated with BOS, as well as its possible relationship with associated sociodemographic and occupational variables.

The selected population consisted of all specialist doctors affiliated with the three regional hospitals, representing the entirety of the MAG, Mexico, who were included in the study if they met the following requirements: having more than one year of experience and being active and available to complete the evaluation instruments. Resident physicians, managers and other healthcare personnel were excluded, as were those not on duty during the survey period, in which case the survey was completed by the personnel covering for them. Surveys that were not filled in correctly were not taken into account. The reasons for and the objectives of the study were explained to the specialist medical personnel. Their authorisation to participate was obtained by means of verbal informed consent, with an emphasis on the anonymous, voluntary and risk-free nature of their participation therein.

Two instruments were used to collect information. The first was prepared specifically for this study to record sociodemographic variables (sex, age, whether one had a stable partner, time with stable partner, whether the partner worked and number of children) and occupational variables (area of work, professional experience and experience in current position, work shift, contract type, other job and hours dedicated to other job). The second was a translated and validated version of the original MBI-HSS,4 which had already been used in several studies conducted in Mexico,7 with a confidence interval of 0.57-0.80.

It was a 22-item questionnaire featuring seven response options (a 0-6 Likert scale), with 0 meaning "never" and 6 meaning "daily", and containing the following subscales: EE (nine items), DP (five items) and PA (8 items). Scores for each subscale were determined by adding up the values for the corresponding items, thus enabling evaluation of each worker's level of BOS. The criteria followed by other authors were applied to determine the cut-off points.5,10 To this end, the three subscales were categorised according to low, moderate and high levels. For the EE subscale, ≤18 was low, 19-26 was moderate and ≥27 was high. For the DP subscale, ≤5 was low, 6-9 was moderate and ≥10 was high. PA, by contrast, operated in an inverse manner compared to the others: ≤33 indicated a low sense of accomplishment, 34-39 a moderate sense of accomplishment and ≥40 a sense of accomplishment. BOS was considered to be present if one of the subscales for the inventory was moderately or highly affected.

The data and their relationship to the sociodemographic and occupational variables were studied using the SPSS 15.0 software program. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed to obtain absolute values, percentages and means ± standard deviations depending on the scale for measurement. Inferential analysis was completed with the Epi Info Version 6.1 software program, which aided in calculating odds ratios (ORs) with their respective 95% confidence intervals (95%CI), and the χ2 test (with or without Yates's correction), considering a p value ≤0.05 to be significant.

Ethical considerationsFor the study, classified as minimal risk by the Mexican General Health Law, the participants were asked for their verbal informed consent, with care being taken to uphold confidentiality and the principles of autonomy, justice and beneficence/non-maleficence. The study was approved by the hospitals' independent ethics committees. Efforts were made to inform interested parties of positive results for their attention.

ResultsOf the 600 surveys distributed, 540 met the study criteria and were filled in correctly, for a response rate of 90.0%. The remaining 60 surveys, which were not taken into account as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, showed no significant differences in terms of distribution compared to the variables analysed in the study group.

The sociodemographic background data revealed that the respondents were 56.0% female (p < 0.05), with a mean age of 44.0 ± 7.1 years, and that the under-40 age group was most strongly represented, with 62.0% (p < 0.05). Among the respondents, 57.0% (p < 0.05) had no stable partner, the average time with a stable partner was 15.1 ± 5.6 years, 58.0% (p < 0.05) had been with a stable partner for fewer than 15 years, 49.0% reported that their stable partner worked and 57.0% (p < 0.05) stated that they had no children.

As regards occupational background, the predominant professional specialisation was medical, with 52.0% (p < 0.05), and the respondents had an average of 15.1 ± 6.3 years of professional experience and 9.0 ± 7.2 years of experience in their current position. The group with fewer than 10 years of occupational experience comprised 55.0% (p < 0.05), and the group with fewer than 10 years of experience in their current position accounted for 49.0%. Within the sample, 59.0% stated that they had a compressed work week, 48.0% stated that they had a permanent contract (p < 0.05), 51.0% did not have another job, and 41.0% worked more than four hours at another job (p < 0.05).

BOS was detected in 248 (45.9%); of them, 113 (45.5%) had one affected subscale; 91 (36.7%) had two and 44 (17.8%) had three.

Regarding the hospital at which they practised, the highest rate of BOS was seen at Regional Hospital C, in 90 (16.7%), followed by Regional Hospital B, in 89 (16.4%), and Regional Hospital A, in 69 (12.8%).

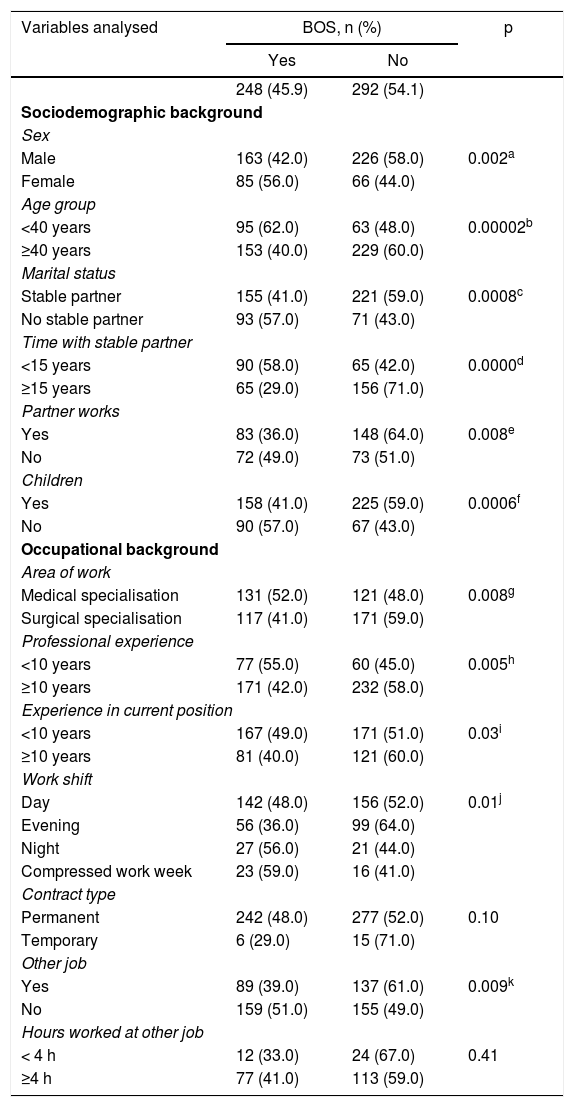

Two groups were then characterised according to the scores achieved to consider BOS:5,10 an affected group and an unaffected group. An association with each of sociodemographic and occupational variable was immediately made. Note in Table 2 that being female, having no stable partner, having a stable partner who did not work, not having children, having a compressed work week and not having another job were associated with BOS, whereas being under 40 years of age (OR = 2.26; 95% CI = 1.52-3.36), having had a stable partner for fewer than 15 years (OR = 3.32; 95% CI = 2.11-5.24), having a medical specialisation (OR = 1.58; 95% CI = 1.11-2.26), having fewer than 10 years of professional experience (OR = 1.74; 95% CI = 1.16-2.62) and having fewer than 10 years of experience in one's current position (OR = 1.46; 95% CI = 1.01-2.11) were associated with BOS and behaved as risk factors.

Relationship of variables associated with the presence or absence of BOS among specialist doctors from three regional hospitals in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2019 (n = 540).

| Variables analysed | BOS, n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| 248 (45.9) | 292 (54.1) | ||

| Sociodemographic background | |||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 163 (42.0) | 226 (58.0) | 0.002a |

| Female | 85 (56.0) | 66 (44.0) | |

| Age group | |||

| <40 years | 95 (62.0) | 63 (48.0) | 0.00002b |

| ≥40 years | 153 (40.0) | 229 (60.0) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Stable partner | 155 (41.0) | 221 (59.0) | 0.0008c |

| No stable partner | 93 (57.0) | 71 (43.0) | |

| Time with stable partner | |||

| <15 years | 90 (58.0) | 65 (42.0) | 0.0000d |

| ≥15 years | 65 (29.0) | 156 (71.0) | |

| Partner works | |||

| Yes | 83 (36.0) | 148 (64.0) | 0.008e |

| No | 72 (49.0) | 73 (51.0) | |

| Children | |||

| Yes | 158 (41.0) | 225 (59.0) | 0.0006f |

| No | 90 (57.0) | 67 (43.0) | |

| Occupational background | |||

| Area of work | |||

| Medical specialisation | 131 (52.0) | 121 (48.0) | 0.008g |

| Surgical specialisation | 117 (41.0) | 171 (59.0) | |

| Professional experience | |||

| <10 years | 77 (55.0) | 60 (45.0) | 0.005h |

| ≥10 years | 171 (42.0) | 232 (58.0) | |

| Experience in current position | |||

| <10 years | 167 (49.0) | 171 (51.0) | 0.03i |

| ≥10 years | 81 (40.0) | 121 (60.0) | |

| Work shift | |||

| Day | 142 (48.0) | 156 (52.0) | 0.01j |

| Evening | 56 (36.0) | 99 (64.0) | |

| Night | 27 (56.0) | 21 (44.0) | |

| Compressed work week | 23 (59.0) | 16 (41.0) | |

| Contract type | |||

| Permanent | 242 (48.0) | 277 (52.0) | 0.10 |

| Temporary | 6 (29.0) | 15 (71.0) | |

| Other job | |||

| Yes | 89 (39.0) | 137 (61.0) | 0.009k |

| No | 159 (51.0) | 155 (49.0) | |

| Hours worked at other job | |||

| < 4 h | 12 (33.0) | 24 (67.0) | 0.41 |

| ≥4 h | 77 (41.0) | 113 (59.0) | |

BOS: burnout syndrome.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.05.

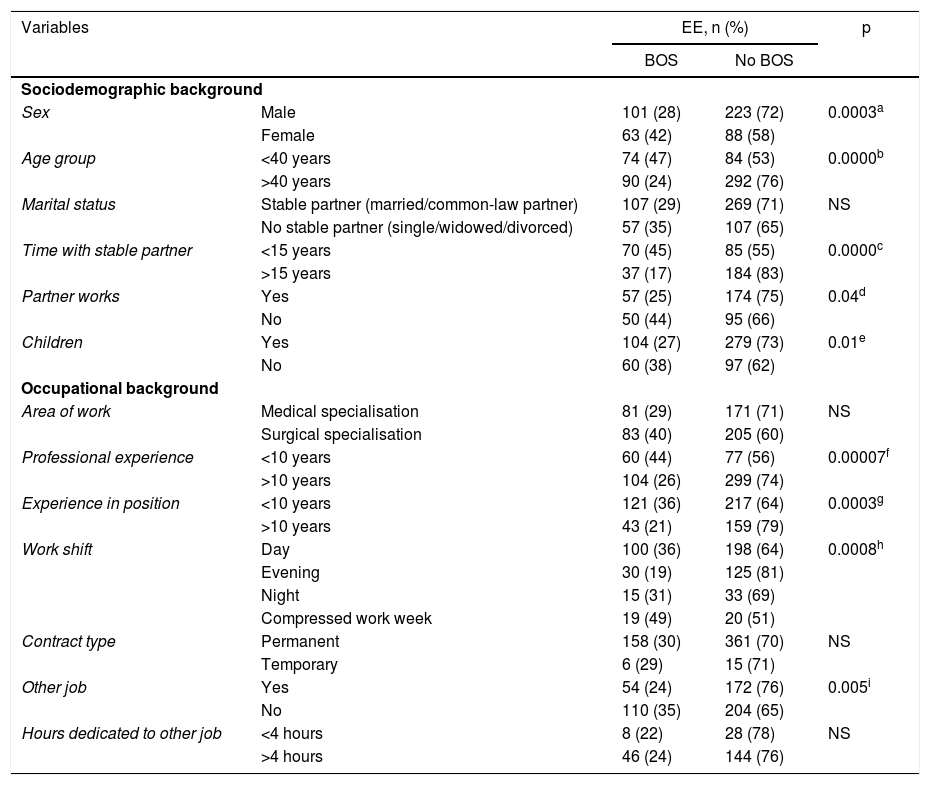

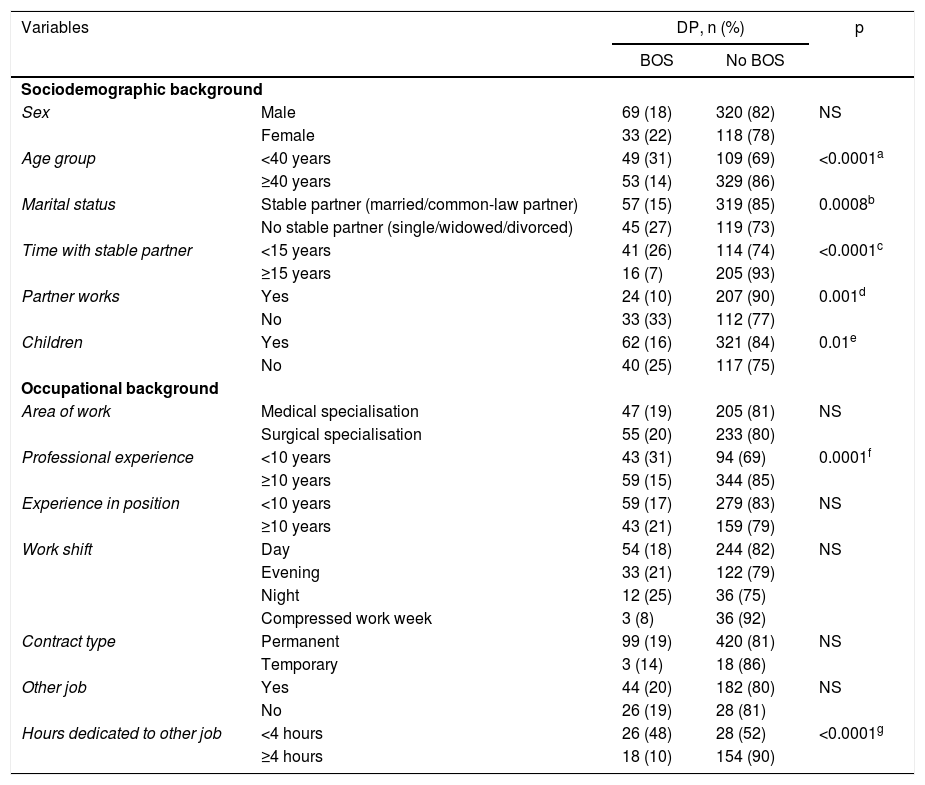

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 show the data collected for the characteristics associated with the EE, DP and PA subscales, respectively, with the presence or absence of BOS.

Characteristics of variables associated with the emotional exhaustion subscale with the presence or absence of BOS among specialist doctors at three regional hospitals in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2019 (n = 540).

| Variables | EE, n (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOS | No BOS | |||

| Sociodemographic background | ||||

| Sex | Male | 101 (28) | 223 (72) | 0.0003a |

| Female | 63 (42) | 88 (58) | ||

| Age group | <40 years | 74 (47) | 84 (53) | 0.0000b |

| >40 years | 90 (24) | 292 (76) | ||

| Marital status | Stable partner (married/common-law partner) | 107 (29) | 269 (71) | NS |

| No stable partner (single/widowed/divorced) | 57 (35) | 107 (65) | ||

| Time with stable partner | <15 years | 70 (45) | 85 (55) | 0.0000c |

| >15 years | 37 (17) | 184 (83) | ||

| Partner works | Yes | 57 (25) | 174 (75) | 0.04d |

| No | 50 (44) | 95 (66) | ||

| Children | Yes | 104 (27) | 279 (73) | 0.01e |

| No | 60 (38) | 97 (62) | ||

| Occupational background | ||||

| Area of work | Medical specialisation | 81 (29) | 171 (71) | NS |

| Surgical specialisation | 83 (40) | 205 (60) | ||

| Professional experience | <10 years | 60 (44) | 77 (56) | 0.00007f |

| >10 years | 104 (26) | 299 (74) | ||

| Experience in position | <10 years | 121 (36) | 217 (64) | 0.0003g |

| >10 years | 43 (21) | 159 (79) | ||

| Work shift | Day | 100 (36) | 198 (64) | 0.0008h |

| Evening | 30 (19) | 125 (81) | ||

| Night | 15 (31) | 33 (69) | ||

| Compressed work week | 19 (49) | 20 (51) | ||

| Contract type | Permanent | 158 (30) | 361 (70) | NS |

| Temporary | 6 (29) | 15 (71) | ||

| Other job | Yes | 54 (24) | 172 (76) | 0.005i |

| No | 110 (35) | 204 (65) | ||

| Hours dedicated to other job | <4 hours | 8 (22) | 28 (78) | NS |

| >4 hours | 46 (24) | 144 (76) | ||

BOS: burnout syndrome; EE: emotional exhaustion; NS: not statistically significant.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.5.

Characteristics of variables associated with the depersonalisation subscale with the presence or absence of BOS among specialist doctors at three regional hospitals in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2019 (n = 540).

| Variables | DP, n (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOS | No BOS | |||

| Sociodemographic background | ||||

| Sex | Male | 69 (18) | 320 (82) | NS |

| Female | 33 (22) | 118 (78) | ||

| Age group | <40 years | 49 (31) | 109 (69) | <0.0001a |

| ≥40 years | 53 (14) | 329 (86) | ||

| Marital status | Stable partner (married/common-law partner) | 57 (15) | 319 (85) | 0.0008b |

| No stable partner (single/widowed/divorced) | 45 (27) | 119 (73) | ||

| Time with stable partner | <15 years | 41 (26) | 114 (74) | <0.0001c |

| ≥15 years | 16 (7) | 205 (93) | ||

| Partner works | Yes | 24 (10) | 207 (90) | 0.001d |

| No | 33 (33) | 112 (77) | ||

| Children | Yes | 62 (16) | 321 (84) | 0.01e |

| No | 40 (25) | 117 (75) | ||

| Occupational background | ||||

| Area of work | Medical specialisation | 47 (19) | 205 (81) | NS |

| Surgical specialisation | 55 (20) | 233 (80) | ||

| Professional experience | <10 years | 43 (31) | 94 (69) | 0.0001f |

| ≥10 years | 59 (15) | 344 (85) | ||

| Experience in position | <10 years | 59 (17) | 279 (83) | NS |

| ≥10 years | 43 (21) | 159 (79) | ||

| Work shift | Day | 54 (18) | 244 (82) | NS |

| Evening | 33 (21) | 122 (79) | ||

| Night | 12 (25) | 36 (75) | ||

| Compressed work week | 3 (8) | 36 (92) | ||

| Contract type | Permanent | 99 (19) | 420 (81) | NS |

| Temporary | 3 (14) | 18 (86) | ||

| Other job | Yes | 44 (20) | 182 (80) | NS |

| No | 26 (19) | 28 (81) | ||

| Hours dedicated to other job | <4 hours | 26 (48) | 28 (52) | <0.0001g |

| ≥4 hours | 18 (10) | 154 (90) | ||

BOS: burnout syndrome; DP: depersonalisation; EE: emotional exhaustion; NS: not statistically significant.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.5.

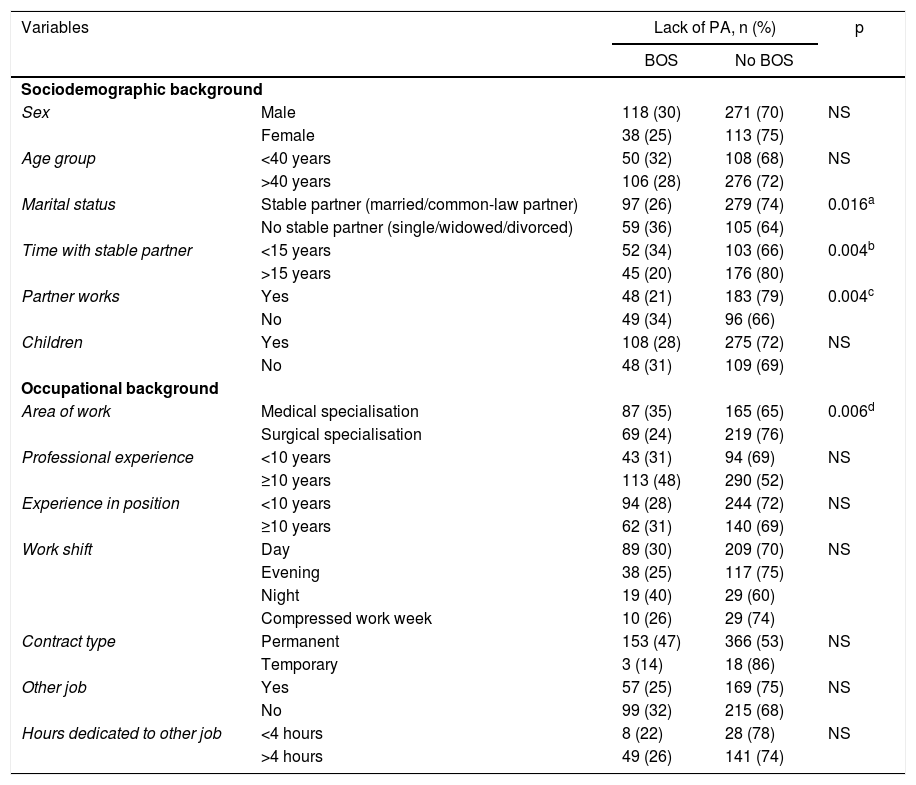

Characteristics of variables associated with the lack of personal accomplishment at work subscale with the presence or absence of BOS among specialist doctors at three regional hospitals in the city of Guadalajara, Mexico, in 2019 (n = 540).

| Variables | Lack of PA, n (%) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOS | No BOS | |||

| Sociodemographic background | ||||

| Sex | Male | 118 (30) | 271 (70) | NS |

| Female | 38 (25) | 113 (75) | ||

| Age group | <40 years | 50 (32) | 108 (68) | NS |

| >40 years | 106 (28) | 276 (72) | ||

| Marital status | Stable partner (married/common-law partner) | 97 (26) | 279 (74) | 0.016a |

| No stable partner (single/widowed/divorced) | 59 (36) | 105 (64) | ||

| Time with stable partner | <15 years | 52 (34) | 103 (66) | 0.004b |

| >15 years | 45 (20) | 176 (80) | ||

| Partner works | Yes | 48 (21) | 183 (79) | 0.004c |

| No | 49 (34) | 96 (66) | ||

| Children | Yes | 108 (28) | 275 (72) | NS |

| No | 48 (31) | 109 (69) | ||

| Occupational background | ||||

| Area of work | Medical specialisation | 87 (35) | 165 (65) | 0.006d |

| Surgical specialisation | 69 (24) | 219 (76) | ||

| Professional experience | <10 years | 43 (31) | 94 (69) | NS |

| ≥10 years | 113 (48) | 290 (52) | ||

| Experience in position | <10 years | 94 (28) | 244 (72) | NS |

| ≥10 years | 62 (31) | 140 (69) | ||

| Work shift | Day | 89 (30) | 209 (70) | NS |

| Evening | 38 (25) | 117 (75) | ||

| Night | 19 (40) | 29 (60) | ||

| Compressed work week | 10 (26) | 29 (74) | ||

| Contract type | Permanent | 153 (47) | 366 (53) | NS |

| Temporary | 3 (14) | 18 (86) | ||

| Other job | Yes | 57 (25) | 169 (75) | NS |

| No | 99 (32) | 215 (68) | ||

| Hours dedicated to other job | <4 hours | 8 (22) | 28 (78) | NS |

| >4 hours | 49 (26) | 141 (74) | ||

BOS: burnout syndrome; PA: personal accomplishment at work; NS: not (statistically) significant.

The threshold for statistical significance was set at p ≤ 0.5.

The following were associated with the presence of BOS for the presence of EE: being female, having a partner who did not work, not having children, having a compressed work week and not having another job. In addition, being under 40 years of age (OR = 2.86; 95% CI = 1.90-4.31), having a stable partner for fewer than 15 years (OR = 4.10; 95% CI = 2.48-6.77), having fewer than 10 years of professional experience (OR = 2.24; 95% CI = 1.47-3.43) and having fewer than 10 years of experience in one's current position (OR = 2.00; 95% CI = 1.35-3.15) were associated with BOS, with their values indicating that they behaved as risk factors.

The following were associated with the presence of BOS for the presence of DP: not having a stable partner, having a stable partner who did not work and not having children. On the other hand, being under 40 years of age (OR = 2.79; 95% CI = 1.75-4.46), having a stable partner for fewer than 15 years (OR = 4.61; 95% CI = 2.38-9.01), having fewer than 10 years of professional experience (OR = 2.67; 95% CI = 1.65-4.31) and dedicating fewer than four hours to another job (OR = 7.94; 95% CI = 3.64-17.51) were associated with the presence of BOS.

The following were associated as risk variables with the presence of BOS for the presence of PA: not having a stable partner and having a stable partner who did not work. In addition, having a stable partner for fewer than 15 years (OR = 1.97; 95% CI = 1.21-3.24) and having a medical specialisation (OR = 1.67; 95% CI = 1.13-2.48) were associated with the presence of BOS.

The following behaved as protective factors against BOS: being female (OR = 0.56; 95% CI = 0.38-0.83), not having a stable partner (OR = 0.54; 95% CI = 0.36-0.79), having a stable partner who did not work (OR = 0.57; 95% CI = 0.36-0.89), not having children (OR = 0.52; 95% CI = 0.35-0.77) and not having another job (OR = 0.63; 95% CI = 0.44-0.91).

A Pearson correlation was made between BOS and each of the three subscales, showing an inversely proportional association of EE (–0.663; p = 0.0001) and DP (–0.490; p = 0.0001) and a directly proportional association of PA (0.644; p = 0.0001).

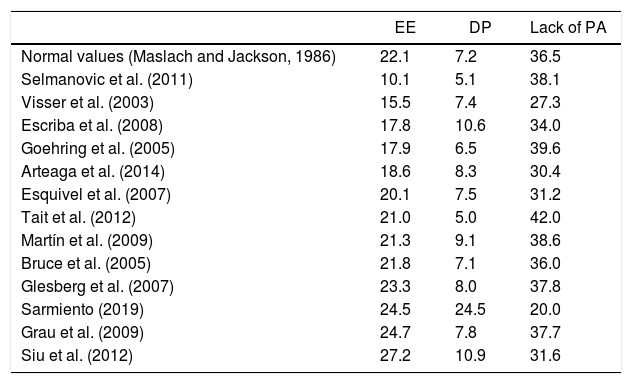

The mean values on the AE, DP and PA subscales in our study were established (15.3, 4.8 and 39.8, respectively). Table 6 compares them with those of various authors.

Mean values on the emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation and lack of personal accomplishment at work subscales for BOS among specialist physicians according to various authors.

| EE | DP | Lack of PA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal values (Maslach and Jackson, 1986) | 22.1 | 7.2 | 36.5 |

| Selmanovic et al. (2011) | 10.1 | 5.1 | 38.1 |

| Visser et al. (2003) | 15.5 | 7.4 | 27.3 |

| Escriba et al. (2008) | 17.8 | 10.6 | 34.0 |

| Goehring et al. (2005) | 17.9 | 6.5 | 39.6 |

| Arteaga et al. (2014) | 18.6 | 8.3 | 30.4 |

| Esquivel et al. (2007) | 20.1 | 7.5 | 31.2 |

| Tait et al. (2012) | 21.0 | 5.0 | 42.0 |

| Martín et al. (2009) | 21.3 | 9.1 | 38.6 |

| Bruce et al. (2005) | 21.8 | 7.1 | 36.0 |

| Glesberg et al. (2007) | 23.3 | 8.0 | 37.8 |

| Sarmiento (2019) | 24.5 | 24.5 | 20.0 |

| Grau et al. (2009) | 24.7 | 7.8 | 37.7 |

| Siu et al. (2012) | 27.2 | 10.9 | 31.6 |

BOS: burnout syndrome; DP: depersonalisation; EE: emotional exhaustion; PA: personal accomplishment at work.

The study of BOS has grown in complexity as its possible causes, determinants and adjacent processes have been identified and evaluated in greater and greater depth. Our study on this subject in a representative sample of specialist doctors from three hospitals in Guadalajara, Mexico, had the strength of providing evidence not only verifying the growing importance of the magnitude of BOS in healthcare and its effects on healthcare personnel, but also reporting and analysing associated factors.

Our study, like all cross-sectional studies, had the limitation of not duly distinguishing causes from effects.

The main limitations of the study were related to its cross-sectional design and some of the properties of the data collection instrument used, i.e., the structured questionnaire, which limited the responses of the study subjects to the options available, thus restricting explanation and in-depth exploration of the topic researched. Other possible limitations were: memory bias and personal reservations on the part of the respondents for fear of the information provided being used to their detriment. Memory bias was addressed by using validated questionnaires, efforts were made to avoid personal reservations by asking specific and objective questions and the anonymity of the respondents was ensured in an attempt to mitigate said fear.

The above was achieved in our study with a 90.0% response rate, which, coupled with the sample size, offered a representative sample of specialist physicians in Guadalajara, Mexico, reflecting a high rate compared to some published studies11–20 and a lower rate compared to others.21–24

As regards sociodemographic background, female sex was a notable variable in our study, consistent with the medical literature reviewed,9,16,23,25,26 and proved significant. This was inconsistent with the findings of other authors who detected a male predominance.8,11–15,17,19,20,22,27,28,30–36 In 2003, Hernández37 found equal proportions in both sexes. A 2004 study by Ordenes21 and a 2002 study by Linzer et al.38 found no significant differences with respect to sex. Age was also analysed, and a higher number of cases was seen in the under-40 age group, in line with the studies reviewed,9,22–25,27–29,31,32,37 and it showed a significant association. This was not consistent with other publications12–20,30,33–36 with a predominance of physicians over 40 years of age. The 2004 Ordenes study21 found no significant age-related differences. Not having a stable partner was found at a higher rate in our study and was significantly associated. This was in line with the findings of Esquivel et al.19 and Lugo.28 In most publications, having a stable partner prevailed.8,9,11–13,15–23,27,30,34,39 Ordenes21 found no significant differences between having one and not having one. In our study, both having a stable partner for fewer than 15 years and having a stable partner who worked were both significantly associated. These variables were not reported in the studies reviewed. Not having children proved significant for us, as it did for Siu et al.;22 however, for other researchers11,12,19,23,36 having children proved significant. For Grau et al.,36 having children had a protective effect.

Concerning occupational background, a medical specialisation was significantly associated, as in other studies,17–19,34 although not those of Cotrina et al.,8 Lugo28 and Miraval,30 in which a surgical specialisation proved significant. Having fewer than 10 years of professional experience was associated with a significant difference in our study, in line with some studies from other authors8,25,31,32 but not in line with others11,17–20,22,26,33,34,36–38 in which more than 10 years of experience predominated. Ordenes21 found no significant differences in this regard; having fewer than 10 years of experience in one's current position proved significant, in line with Martín et al.25 Having more than 10 years of experience was not reported in the studies reviewed. Regarding work shifts, having a compressed work week had a significant association; this variable was not reported in the studies examined. A permanent contract type predominated in our study, consistent with the findings of Cotrina et al.8 For Sarmiento,24 a temporary contract prevailed. Not having another job proved was associated in our study, unlike those of other authors.12,20,23,34 For Sabag40 having another job was significantly associated. Working more than four hours at another job prevailed in this study and was significant; other authors did not record it.

To contextualise our study, a broad review on the prevalence of BOS in specialist doctors was conducted (Table 1). This placed us above most studies conducted8,12–15,17–21,24,27–30,32,35–42 and showed a great deal of variability in the frequency of the syndrome, in turn revealing the complex character of its components. It also placed us below other authors.9,11,15,22,23,31,33

Consistent traits of association were found: BOS, EE, DP and PA together were consistently associated with having a stable partner for more than 15 years and having a stable partner who did not work. BOS, EE and PA were consistently associated with not having a stable partner. BOS, EE and DP were consistently associated with being under 40 years of age, not having children and having fewer than 10 years of professional experience. BOS and EE were consistently associated with being female, having fewer than 10 years of experience in one's current position, having a compressed work week, not having another job and dedicating more than four hours to another job. BOS and DP were consistently associated with having a medical specialisation.

The mean values for the EE and DP subscales were within low normal limits. PA had a score within the high level (Table 6).

The establishment of a negative correlation with the presence of BOS between the EE and DP subscales and a positive correlation with the PA subscale was consistent with the findings of Salanova et al.43 This result has also been confirmed by means of structural equation modelling.44,45 The EE subscale was confirmed to be the most reliable subscale for the syndrome. Schaufeli and Enzmann46 mentioned that the two central dimensions of the syndrome, lying at the heart of it, are EE and DP.47

Hence, BOS was concluded to be common (45.9%) among specialist doctors. Its main associated variables were being female, under 40 years of age, not having a stable partner, having a stable partner for fewer than 15 years, having a stable partner who worked, not having children, having a medical specialisation, having fewer than 10 years of professional experience, having fewer than 10 years of experience in one's current position, having a compressed work week, having a permanent contract, not having another job and working more than four hours at another job. Being affected by EE and DP behaved like the syndrome. The mean levels of the subscales were generally found to be close to normal. A negative correlation was found between the EE and DP subscales, and a positive correlation was found between a lack of PA at work and the presence of the syndrome. The above calls for consideration of the need to establish preventive and interventional measures on individual, social and organisational levels to bring down the prevalence found.

Please cite this article as: Castañeda Aguilera E, García JEGdA. Prevalencia del síndrome de agotamiento profesional (burnout) y variables asociadas en médicos especialistas. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:41–50.