The systematic formulation of the research question allows the researcher to focus the study, guide the method decisions, and to put forward possible solutions. In practice, there are difficulties in the formulation of research problems. Diversity of clinical scenarios can lead to a mismatch between the structure of the research question and the classical PICO (population, intervention, control, and outcomes) format. The aim of this article is to provide guidelines that help in the proper formulation of clinical practice research questions for general practitioners, specialists, and healthcare personnel in training.

La elaboración sistemática de la pregunta de investigación permite al investigador enfocar el problema, orientar los métodos y postular posibles soluciones. En la práctica, todavía se observan dificultades en la formulación del problema de investigación. La diversidad de los escenarios clínicos, de donde resulta buena parte de las preguntas de investigación, hace que su formulación no se ajuste siempre a la estrategia PICO. El objetivo de este artículo es aportar una guía que facilite la formulación de las preguntas de investigación que surgen en la práctica clínica a médicos, especialistas y personal en entrenamiento.

The correct formulation of a question is one of the first critical steps in the process of preparing a research study. It helps the researcher to focus on the problem and identify the study variables, the population and the possible outcomes. The research question is the structural axis of the protocol. It guides the development of the theoretical framework, the conceptual hypothesis and the objectives. It also facilitates the selection of the type of epidemiological design that can best answer the particular type of question.1,2 At the same time, it facilitates the search for scientific information3 through the specification of search terms,4,5 which helps establish the state of the art and, consequently, identify gaps in knowledge of interest to the scientific community.

In routine practice it is very often difficult to identify the elements of the question and achieve suitable wording that matches the intention of the researcher. In order to help researchers in their work, strategies have been developed that simplify the formulating of research questions.6–9 However, there are reports of difficulties in prioritising the questions, insufficient time to formulate and answer them and a lack of tools to carry out an efficient review of the literature.10,11 Another obstacle identified is that formulating strategies, such as PICO,12 are too rigid and do not fit the various research scenarios.

Research objectives are not met because of errors in the expression of the problem and incomplete, imprecise or confusing formulation of the question. As a result, the information obtained from the research process does not always provide the expected responses to the original questions. The objective of this article is to provide general practitioners, specialists and healthcare personnel in training with some key points to facilitate the formulating of research questions, in order to make their writing more efficient and ensure a successful start to the research process.

DefinitionThe research question is a structured question asked by the researcher about a subject of interest based on a problem that the scientific community has not solved. The problem can be defined as a situation that has invalid, disputed or insufficient results for the generation of conclusions (knowledge gap).13 It is important to differentiate the research question from clinical questions, which are designed to cross the knowledge boundaries of the individual posing them, but not of the scientific community. The current strategy for answering that type of question is evidence-based medicine (EBM). However, after an exhaustive search and critical analysis of the literature, that clinical question may be the starting point from which to identify a gap in knowledge, and then be transformed into a research question.

ClassificationResearch questions are classified into three categories, according to the purpose, objective and clinical context.14 The purpose is what the researcher intends with the question they are formulating. For this there are two basic options: to describe a phenomenon of nature at a specific point in time and space (descriptive); or compare interventions, techniques or exposures to determine their association with an outcome (inferential or analytical).

The question's objective is the specific outcome expected by the researcher. If it is about the variability of some clinical or epidemiological aspect, the question is quantitative. If, however, the researcher expects to obtain new categories or processes associated with a phenomenon, the question will be qualitative.

The clinical context is the most used in EBM and defines the universe of clinical activities in which the question is immersed. Clinical practice includes four basic activities: the identification of risk factors (aetiology, causality); the detection of diseases based on questioning, physical examination and paraclinical data (diagnosis); prevention or treatment (intervention); and prediction of the consequences of the condition over time (prognosis).

StructureDescriptiveThe structure of the descriptive questions includes the following elements: an interrogative adjective (which, how much, who); the measurement (prevalence, incidence); a condition (depression, anxiety); the population; the place; and the time.14 This defines a very specific population to which the results would be generalised. Questions about frequencies such as prevalence and incidence belong in this structure.

InferentialThe strategy most used in clinical practice to structure inferential questions is PICO.12 This format includes population (P); intervention, exposure or diagnostic technique (I, E or T, respectively) comparison (C) and an outcome (O). Within the framework of EBM, the ‘T’ is sometimes used to establish the type of study that would best answer the clinical question,4 but for research questions it would be equivalent to the follow-up time of the condition or the time in which it is expected to take effect (PICOT).12,15

One category not included in this strategy, but which would avoid confusion in the wording of the question, is measurement (M). The researcher has to determine whether they want to measure the effect of an intervention, the risk of suffering an outcome due to the presence of a particular factor or the operating characteristics of a diagnostic test.

Guidelines are provided below on quantitative questions in the clinical context, which include a proposed structure.

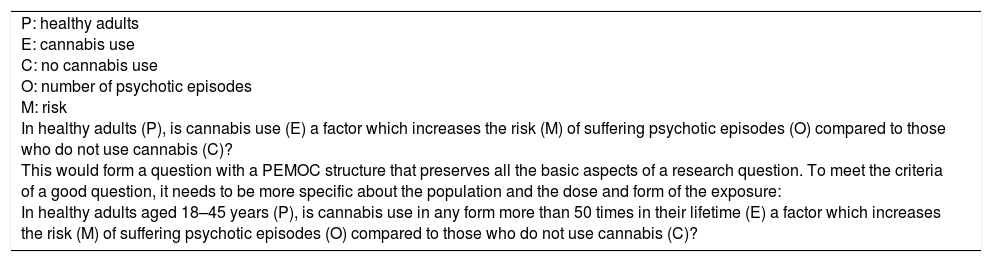

Aetiology or causalityThese questions have negative connotations. They arise when the researcher thinks of a factor that will increase the likelihood of suffering from a disease or condition. Some examples of risk factors are: use of psychoactive substances, tobacco or alcohol; sedentary lifestyle; and noise.

The population in this scenario is “healthy” people or people who do not suffer from the disease in question. Exposure is the risk factor being studied, and the comparison is the absence of that factor. The outcome is the presence of the disease. It is important to add measurement (M) here for adequate wording of the question. For questions of aetiology or causality, what we want to measure is risk. According to the substantive hypothesis developed from the theoretical framework, the researcher can add at a later point the expected time for the exposure to take effect and produce the outcome, i.e. the minimum time patients will be followed up. This point is important because the risk does not make sense without a measurement time span attached to it (Example 1).

Causality question.

| P: healthy adults E: cannabis use C: no cannabis use O: number of psychotic episodes M: risk In healthy adults (P), is cannabis use (E) a factor which increases the risk (M) of suffering psychotic episodes (O) compared to those who do not use cannabis (C)? This would form a question with a PEMOC structure that preserves all the basic aspects of a research question. To meet the criteria of a good question, it needs to be more specific about the population and the dose and form of the exposure: In healthy adults aged 18–45 years (P), is cannabis use in any form more than 50 times in their lifetime (E) a factor which increases the risk (M) of suffering psychotic episodes (O) compared to those who do not use cannabis (C)? |

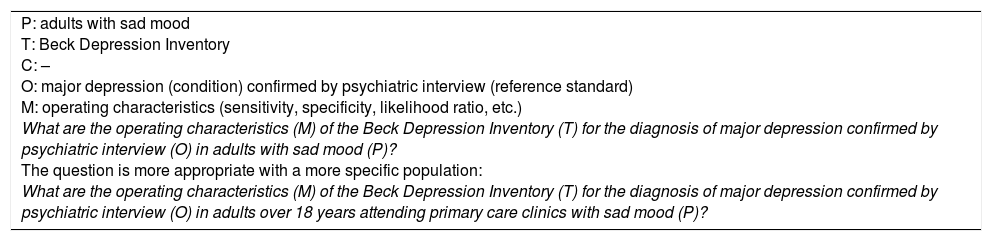

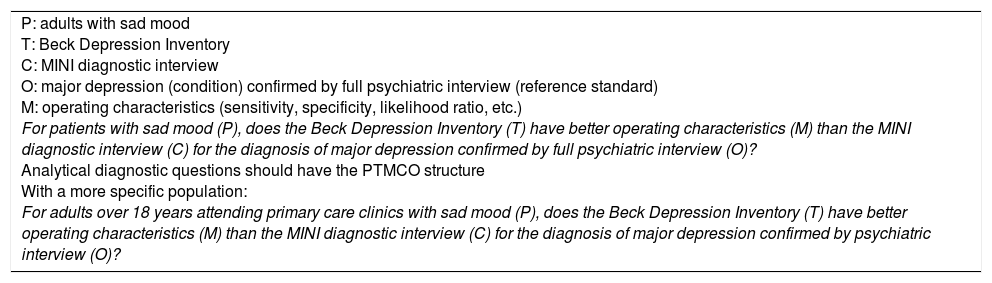

Questions about diagnostic accuracy are particularly difficult to formulate. Contrary to what is generally thought, they usually have a descriptive structure. The purpose of these questions is to determine the ability of a test to correctly discern whether or not a patient suffers from a disease according to the result of a gold standard. The origin of the confusion is that: (a) there is an implicit comparison with a gold (or reference) standard that confirms the disease to be diagnosed, for which it would be considered analytical, when that is not the case; and (b) it is believed erroneously that the operating characteristics of the technique being tested are generalised beyond the population to which it was applied, i.e. they are an intrinsic part of the test in any population context.16,17 However, purely analytical diagnostic questions enter the clinical scenario when two techniques are compared to determine which has the best operating characteristics, by confirming the disease with a gold standard.

The population (P) in questions of diagnostic accuracy is subjects in whom a condition is suspected. This is not an intervention from which we expect to obtain an effect, although that remains subject to debate.18,19 What we want to assess in these questions is the index test, so the comparison (C) would be another technique (control). The outcome, as is common in clinical activity, is the disease, which must be confirmed (hopefully) by the best available test (gold standard).20 What we want to measure (M) are the operating characteristics (diagnostic accuracy) of the test: sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratios or the area under the curve. It is important to highlight that, in both inferential and descriptive diagnostic questions, the outcome (O) is the disease confirmed by a gold standard.21

To sum up, for the evaluation of diagnostic tests, descriptive or analytical questions can be asked. If the aim is to describe the characteristics of the test when the disease is confirmed with a reference standard, the question will be descriptive. If what is sought is to assess which test performs better (index versus control), the structure should be analytical.

As previously suggested, the writing of diagnostic questions in which no explicit comparison is made goes more with the structure of a descriptive question than with that of an analytical one (Examples 2 and 3).

Diagnostic accuracy question (without comparison and not descriptive).

| P: adults with sad mood T: Beck Depression Inventory C: – O: major depression (condition) confirmed by psychiatric interview (reference standard) M: operating characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio, etc.) What are the operating characteristics (M) of the Beck Depression Inventory (T) for the diagnosis of major depression confirmed by psychiatric interview (O) in adults with sad mood (P)? The question is more appropriate with a more specific population: What are the operating characteristics (M) of the Beck Depression Inventory (T) for the diagnosis of major depression confirmed by psychiatric interview (O) in adults over 18 years attending primary care clinics with sad mood (P)? |

Diagnostic accuracy question (with comparison or analytical).

| P: adults with sad mood T: Beck Depression Inventory C: MINI diagnostic interview O: major depression (condition) confirmed by full psychiatric interview (reference standard) M: operating characteristics (sensitivity, specificity, likelihood ratio, etc.) For patients with sad mood (P), does the Beck Depression Inventory (T) have better operating characteristics (M) than the MINI diagnostic interview (C) for the diagnosis of major depression confirmed by full psychiatric interview (O)? Analytical diagnostic questions should have the PTMCO structure With a more specific population: For adults over 18 years attending primary care clinics with sad mood (P), does the Beck Depression Inventory (T) have better operating characteristics (M) than the MINI diagnostic interview (C) for the diagnosis of major depression confirmed by psychiatric interview (O)? |

There are also circumstances in which the researcher may want to determine the reproducibility of the tests, i.e. how comparable the two techniques or their interpretation are. The aim is to quantify the degree of agreement between two or more evaluators or tests (concordance) to determine whether or not they are interchangeable. The agreement is classified according to conformity and consistency.22 If the results of a technique are compared with those of a gold standard, we use the term conformity. However, if neither of the two tests is considered the diagnostic standard, we use the term consistency.

In the case of a conformity question emerging, where possible, it is advisable to convert it into a diagnostic accuracy question.22 This will make design options available that will provide more complete information about diagnostic performance and the circumstances in which the test should be requested.

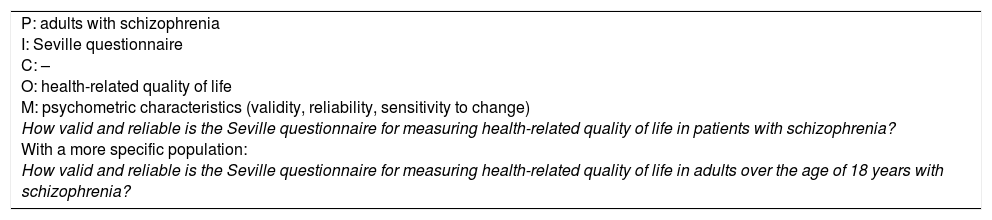

Another situation, which rarely occurs in clinical practice but does in the field of research, is the need to determine the psychometric characteristics of a measurement instrument to establish its validity and reliability. These are usually scales that aim to quantify an abstract concept (construct) such as quality of life, mood or spirituality. This type of scenario does not occur in clinical practice because they are a step back. What that means is that clinicians are already using scales which have been validated up to a certain point and so focus their interest on the operating characteristics (diagnostic accuracy) rather than the psychometric characteristics.

In this “validation” scenario, the objective is to establish whether or not the items in a scale adequately measure the proposed construct, which can be necessary either for the creation of a new scale or to adapt an existing scale to a different cultural environment. Therefore, what the researcher hopes to find is reliability or reproducibility (internal consistency, inter-rater and test-retest reliability), validity, sensitivity to change and clinical utility.23 In terms of structure, these questions will have a descriptive configuration like those of diagnostic accuracy, without explicit comparison. For the population, the researcher must be clear whether the scale is for use in the general population or in patients with a specific condition. The technique being tested will be the scale or measuring instrument. These questions, in general, do not have an explicit comparison. The outcome is the construct to be measured (Example 4).

Scale-validation questions (measurement).

| P: adults with schizophrenia I: Seville questionnaire C: – O: health-related quality of life M: psychometric characteristics (validity, reliability, sensitivity to change) How valid and reliable is the Seville questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in patients with schizophrenia? With a more specific population: How valid and reliable is the Seville questionnaire for measuring health-related quality of life in adults over the age of 18 years with schizophrenia? |

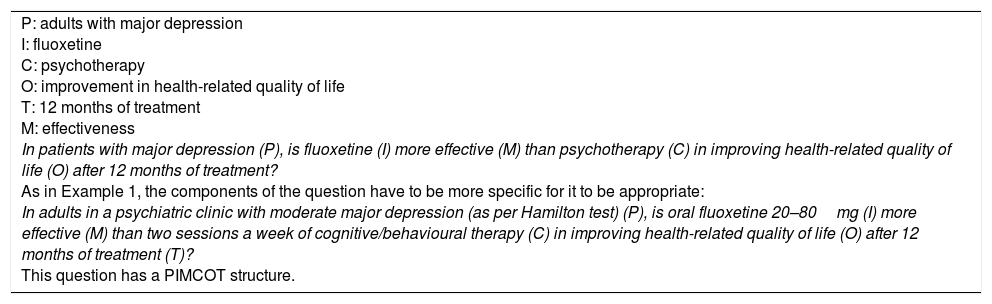

Intervention questions in EBM are usually analytical. The aim of an intervention is to achieve an effect on a condition in order to improve important outcomes for healthcare personnel or the patient (ideally). Interventions are not necessarily pharmacological; they can also be educational or preventive. As previously suggested, they may even be diagnostic. Although the diagnostic technique per se will not produce an effect on the condition, its inclusion in a diagnostic strategy may well change the type of intervention and, consequently, the frequency of outcomes, resulting in better future clinical decision-making.24

For intervention questions, the population will be people with a disease or condition. The intervention will be a pharmacological or educational treatment or a diagnostic strategy. The comparison is another intervention we want to compare it with: placebo, usual treatment, active treatment, simulation or no intervention. The outcome is the occurrence of disease-related events, such as morbidity and mortality or health-related quality of life. The measurement we hope to obtain is an effect, which is translated in technical terms into efficacy (ideal conditions) or effectiveness (actual conditions). The time at which the intervention is expected to take effect should also be included in the question (Example 5).

Intervention question.

| P: adults with major depression I: fluoxetine C: psychotherapy O: improvement in health-related quality of life T: 12 months of treatment M: effectiveness In patients with major depression (P), is fluoxetine (I) more effective (M) than psychotherapy (C) in improving health-related quality of life (O) after 12 months of treatment? As in Example 1, the components of the question have to be more specific for it to be appropriate: In adults in a psychiatric clinic with moderate major depression (as per Hamilton test) (P), is oral fluoxetine 20–80mg (I) more effective (M) than two sessions a week of cognitive/behavioural therapy (C) in improving health-related quality of life (O) after 12 months of treatment (T)? This question has a PIMCOT structure. |

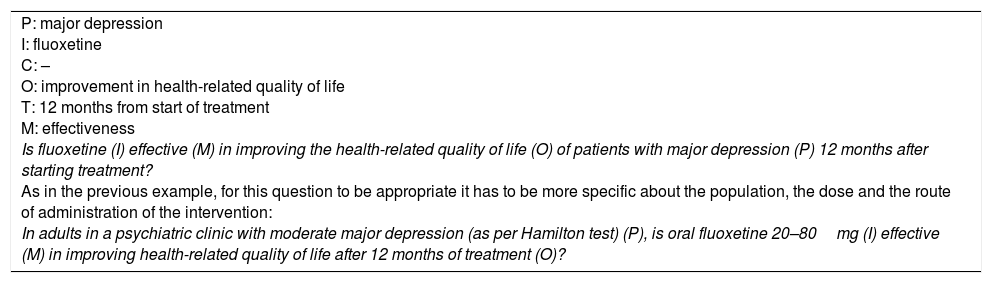

There are situations in which the intervention does not have an explicit comparison with a control, but between before and after. This makes it particularly challenging to formulate the question because what we are comparing are not the interventions, but the outcome. The outcome reveals a tacit change between one time point before and another time point after the intervention. Although the question structure does not have a comparison in C, it is still an analytical scenario (Example 6).

Intervention question without comparison.

| P: major depression I: fluoxetine C: – O: improvement in health-related quality of life T: 12 months from start of treatment M: effectiveness Is fluoxetine (I) effective (M) in improving the health-related quality of life (O) of patients with major depression (P) 12 months after starting treatment? As in the previous example, for this question to be appropriate it has to be more specific about the population, the dose and the route of administration of the intervention: In adults in a psychiatric clinic with moderate major depression (as per Hamilton test) (P), is oral fluoxetine 20–80mg (I) effective (M) in improving health-related quality of life after 12 months of treatment (O)? |

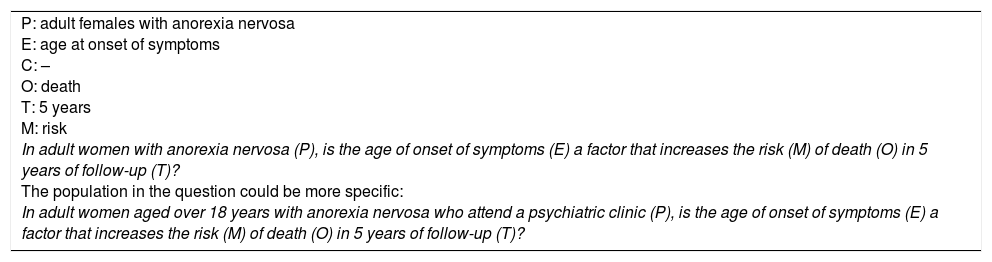

Prognosis questions are difficult to specify because prognosis is, in one way or another, associated with the other types of question. For example, a risk factor for one disease could also be a prognostic factor for another; some diagnostic tests have prognostic capacity and the aim of the treatment is to change the patient's prognosis.

As the prognosis is very often an important element in medical practice, it is a common mistake to confuse this type of question with other types, especially intervention questions. The researcher is not going to apply the prognostic factor (or marker); rather, it is an innate characteristic of the research subject. It can be used to identify which group of people with a condition will fare better or worse in the future.

For identifying prognostic questions, certain elements are required: the population consists of people who suffer from a condition; the exposure does not necessarily have to be causal or have negative connotations; and the time until the outcome must be clearly established. Although the comparison is not explicit, this type of question is analytical in most cases. If the prognostic factor is a categorical variable, the comparison (C) is generally the absence of the factor. For quantitative variables, the cut-off point is sometimes not known until the data has been analysed. It would not therefore be sensible to present a comparison at the beginning. The outcomes of the question are “hard” and very important for the patient, for example: relapse, death, survival or some objective event related to time. What we hope to measure (M) is the risk or the prognostic value (Example 7).

Prognosis question.

| P: adult females with anorexia nervosa E: age at onset of symptoms C: – O: death T: 5 years M: risk In adult women with anorexia nervosa (P), is the age of onset of symptoms (E) a factor that increases the risk (M) of death (O) in 5 years of follow-up (T)? The population in the question could be more specific: In adult women aged over 18 years with anorexia nervosa who attend a psychiatric clinic (P), is the age of onset of symptoms (E) a factor that increases the risk (M) of death (O) in 5 years of follow-up (T)? |

Qualitative research aims to find meaning, interpretations or explanations of a phenomenon that it is not appropriate to quantify.25 Qualitative questions are more common in the human sciences such as anthropology and sociology, but they are appearing with increasing frequency in public health and psychiatry, in the health sciences. The objectives of qualitative studies are to develop hypotheses that can be used as the bases of future studies, theoretical models that facilitate understanding of the meaning people or populations give to complex human or social phenomena26 and even engage in social actions concerning those phenomena.27

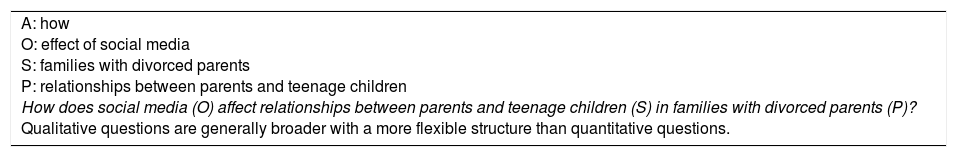

Qualitative questions do not conform to the PICO strategy and have a broad and flexible structure. When researchers propose a central question, they may start with the questions “which”, “how” and “what”, rather than “why”.27 With these questions, three components are identified: the phenomenon or the central situation we wish to study (S); what we aim to find out about the phenomenon or objective of the study (O); and the target population and its context (P)27,28 (Example 8).

Qualitative question.

| A: how O: effect of social media S: families with divorced parents P: relationships between parents and teenage children How does social media (O) affect relationships between parents and teenage children (S) in families with divorced parents (P)? Qualitative questions are generally broader with a more flexible structure than quantitative questions. |

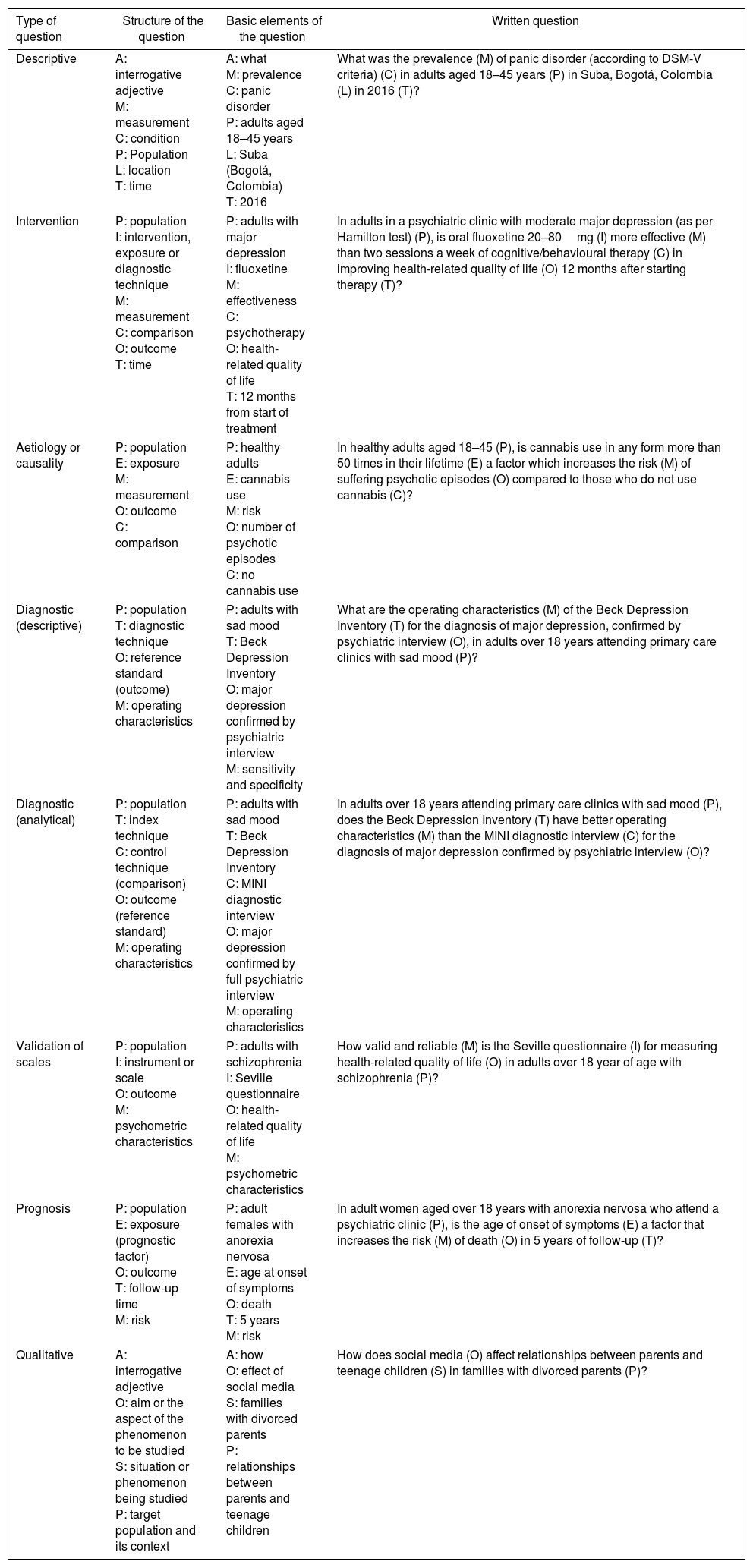

This article presents a guide to formulating research questions for students or researchers in training. The aim is to help with the approach to a clinical problem, the variables involved and the possible outcomes. We have addressed the limitations inherent to the PICO strategy for specific situations in clinical practice and propose the measurement item in order to avoid confusion when developing the structure (Table 1). We also provide a conceptual map which complements the information presented in the text (supplementary material).

Summary of the structure for formulating research questions.

| Type of question | Structure of the question | Basic elements of the question | Written question |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive | A: interrogative adjective M: measurement C: condition P: Population L: location T: time | A: what M: prevalence C: panic disorder P: adults aged 18–45 years L: Suba (Bogotá, Colombia) T: 2016 | What was the prevalence (M) of panic disorder (according to DSM-V criteria) (C) in adults aged 18–45 years (P) in Suba, Bogotá, Colombia (L) in 2016 (T)? |

| Intervention | P: population I: intervention, exposure or diagnostic technique M: measurement C: comparison O: outcome T: time | P: adults with major depression I: fluoxetine M: effectiveness C: psychotherapy O: health-related quality of life T: 12 months from start of treatment | In adults in a psychiatric clinic with moderate major depression (as per Hamilton test) (P), is oral fluoxetine 20–80mg (I) more effective (M) than two sessions a week of cognitive/behavioural therapy (C) in improving health-related quality of life (O) 12 months after starting therapy (T)? |

| Aetiology or causality | P: population E: exposure M: measurement O: outcome C: comparison | P: healthy adults E: cannabis use M: risk O: number of psychotic episodes C: no cannabis use | In healthy adults aged 18–45 (P), is cannabis use in any form more than 50 times in their lifetime (E) a factor which increases the risk (M) of suffering psychotic episodes (O) compared to those who do not use cannabis (C)? |

| Diagnostic (descriptive) | P: population T: diagnostic technique O: reference standard (outcome) M: operating characteristics | P: adults with sad mood T: Beck Depression Inventory O: major depression confirmed by psychiatric interview M: sensitivity and specificity | What are the operating characteristics (M) of the Beck Depression Inventory (T) for the diagnosis of major depression, confirmed by psychiatric interview (O), in adults over 18 years attending primary care clinics with sad mood (P)? |

| Diagnostic (analytical) | P: population T: index technique C: control technique (comparison) O: outcome (reference standard) M: operating characteristics | P: adults with sad mood T: Beck Depression Inventory C: MINI diagnostic interview O: major depression confirmed by full psychiatric interview M: operating characteristics | In adults over 18 years attending primary care clinics with sad mood (P), does the Beck Depression Inventory (T) have better operating characteristics (M) than the MINI diagnostic interview (C) for the diagnosis of major depression confirmed by psychiatric interview (O)? |

| Validation of scales | P: population I: instrument or scale O: outcome M: psychometric characteristics | P: adults with schizophrenia I: Seville questionnaire O: health-related quality of life M: psychometric characteristics | How valid and reliable (M) is the Seville questionnaire (I) for measuring health-related quality of life (O) in adults over 18 year of age with schizophrenia (P)? |

| Prognosis | P: population E: exposure (prognostic factor) O: outcome T: follow-up time M: risk | P: adult females with anorexia nervosa E: age at onset of symptoms O: death T: 5 years M: risk | In adult women aged over 18 years with anorexia nervosa who attend a psychiatric clinic (P), is the age of onset of symptoms (E) a factor that increases the risk (M) of death (O) in 5 years of follow-up (T)? |

| Qualitative | A: interrogative adjective O: aim or the aspect of the phenomenon to be studied S: situation or phenomenon being studied P: target population and its context | A: how O: effect of social media S: families with divorced parents P: relationships between parents and teenage children | How does social media (O) affect relationships between parents and teenage children (S) in families with divorced parents (P)? |

The recommendations proposed here are a starting point for people who do not have the experience to prepare this section of the protocol. In the end, the question has to be based on a firm approach to the problem that takes into account the magnitude, the causes, the possible solutions and the unanswered questions.29 Even if correctly formulated, not all research questions are of interest to a community. Identifying whether or not it is feasible, interesting, novel, ethical and relevant (FINER criteria)30 helps us establish the viability and the expected impact of the problem. Refining the question is then a dynamic process that allows us to modify the structure and the specifications for developing the protocol. With practice, healthcare personnel in research training will create their own writing style, while always maintaining the characteristics of a well-formulated question.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Our thanks to Dr Álvaro Ruiz for his valuable comments in the preparation of this article.

Please cite this article as: Cañón M, Buitrago-Gómez Q. La pregunta de investigación en la práctica clínica: guía para formularla. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2018;47:193–200.