Symptoms of post-traumatic stress are common in people who have experienced a life experience that significantly threatened their physical or psychological integrity. Nevertheless, little information about post-traumatic stress disorder risk (PSTD-R) in Colombian COVID-19 survivors is available.

ObjectiveTo establish the prevalence and variables associated with PTSD-R in a sample of COVID-19 survivors in Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodA cross-sectional study was designed with a non-probabilistic sample of adult COVID-19 survivors. Participants were demographically characterized and completed scales for depression risk, insomnia risk, and PTSD-R.

ResultsThree hundred and thirty COVID-19 survivors between 18 and 89 years participated; 61.5% were women. The frequency of depression risk was 49.7%; insomnia risk, 60.6%; and PTSD-R, 13.3%. Depression risk (OR=41.4, 95% CI 5.5–311.6), insomnia risk (OR=5.3, 95% CI 1.8–18.7), low income (OR=3.5, 95% CI 1.4–8.7) and being married or free union (OR=2.7, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) were associated with PTSD-R.

ConclusionsTwo out of every fifteen COVID-19 survivors are in PTSD-R. Depression and insomnia risk are strongly associated with PTSD-R among Colombian COVID-19 survivors. Studies that follow COVID-19 survivors long-term are needed.

Los síntomas del estrés postraumático son comunes en personas que han vivido una experiencia de vida que amenazó significativamente su integridad física o psicológica. Sin embargo, hay poca información disponible sobre el riesgo de trastorno de estrés postraumático (R-TEPT) en los sobrevivientes colombianos de COVID-19.

ObjetivoEstablecer la prevalencia y las variables asociadas al R-TEPT en una muestra de sobrevivientes de COVID-19 en Santa Marta, Colombia.

MétodoSe diseñó un estudio transversal con una muestra no probabilística de adultos sobrevivientes de COVID-19. Los participantes fueron caracterizados demográficamente y completaron escalas de riesgo de depresión, riesgo de insomnio y R-TEPT.

ResultadosParticiparon 330 sobrevivientes de COVID-19 de entre 18 y 89años; el 61,5% eran mujeres. La frecuencia de riesgo de depresión fue del 49,7%; la de riesgo de insomnio, del 60,6%, y la de R-TEPT, del 13,3%. El riesgo de depresión (OR=41,4; IC95%: 5,5-311,6), el riesgo de insomnio (OR=5,3; IC95%: 1,8-18,7), los bajos ingresos (OR=3,5; IC95%: 1,4-8,7) y estar casado o en unión libre (OR=2,7; IC95%: 1,1-6,2) se asociaron a R-TEPT.

ConclusionesDos de cada 15 supervivientes de COVID-19 se encuentran en R-TEPT. El riesgo de depresión e insomnio está fuertemente asociado al R-TEPT entre los sobrevivientes colombianos de COVID-19. Se necesitan estudios que sigan a los supervivientes de COVID-19 a largo plazo.

Post-traumatic stress symptoms are frequent in people who have lived a life experience that significantly threatened their physical or psychological integrity. Traumatic events include military combat, violent assaults, physical or sexual abuse, natural disasters, and serious accidents. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by intrusive symptoms (distressing memories or dreams), avoidance of situations related to the stressful event (people, places, or conversations), cognitive and mood disturbances (persistent negative beliefs or negative emotions), and reactivity (irritability, hypervigilance or sleep disturbances).1

During the COVID-19 pandemic, high numbers of people from the general population,2 healthcare workers,3 and survivors of infection are at high risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD-R).4–13 The prevalence of PTSD-R is between 5.8% and 34.5% in COVID-19 survivors, depending on the population's characteristics and measurement instrument. The PTSD-R, measured with the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist-5 (PCL-5) in China, Chang et al.4 observed in 64 post-hospitalization survivors that 20.3%. In Norway, Einvik et al.5 out of 1149 participants, found that 7.4% scored for PTSD-R. In Italy, Tarsitani et al.6 in 115 survivors three months after hospital discharge, 10.4% were found to have PTSD-R. In China, Liu et al.7 in a sample of 675 survivors, including 90 doctors and nurses, found that 12.2% scored for PTSD-R. In Iran, Simani et al.8 documented a prevalence of 5.8% six months post-hospitalization. Likewise, the PTSD-R explored with the Impact of Event Scale-Revised in Italy, Bellan et al.9 among 238 survivors of severe COVID-19, observed that 17.2% were in PTSD-R four months after hospital discharge. In Italy, De Lorenzo et al.10 in 185 participants, found that 22.2% had PTSD-R three to four weeks after leaving the hospital. In Turkey, Poyraz et al.11 among 98 survivors approximately two months after discharge, 34.5% reported PTSD-R. In Colombia, Guillen-Burgos et al.12 in 1565 COVID-19 survivors during a 24-month follow-up period, reported that 35.5% presented PTSD-R. More recently, two independent meta-analyses concluded that 16% of COVID-19 survivors have significant symptoms of PTSD.13,14

Variables associated with PTSD-R in COVID-19 survivors are divergent findings. The prevalence of PTSD-R has been observed to be independent of age in research.4,6 Nevertheless, others found that the frequency increased with age.7,15 Likewise, some studies show that PTSD-R frequency is higher in women.5,6,9 However, a more significant number reported no differences by gender.4,7,8,11,15

In the same sense, more cases have been documented in more symptomatic survivors or with greater severity of the infection,5,7 and more days of hospital stay.6,16 However, a lack of relationship between the length of hospitalization and PTSD-R has been reported,4 with even shorter hospital stays with tests related to PTSD-R.7

In addition, it has been shown that the PTSD-R is higher in the presence of comorbidity,6 symptoms for more extended periods,11 the persistence of residual symptoms,15 and symptoms of depression,11,16 or insomnia.11 The relation between treatment in the intensive care unit and PTSD-R is inconsistent,6,7 and no differences were observed in the prevalence of PTSD-R between health workers and the general population,7 outpatient or in-hospital treatment,5 and the discharge time.4

In Colombia, by June 7, 2023, the COVID-19 pandemic had left 6,369,916 confirmed cases, 1625 active cases, 6,190,683 survivors, and 142,780 deaths (rate of 2775 deaths per million inhabitants).17 Consequently, many COVID-19 survivors can be expected to be in PTSD-R. General practitioners who serve a large part of the demand for mental health care in low- and middle-sized countries income such as Colombia should actively investigate symptoms of the PTSD spectrum.18,19 COVID-19 survivors can complete scales to screen PTSD cases in the waiting room.20 Healthcare professionals must confirm the diagnosis of PTSD using a clinical interview1 and initiate the management of most cases.16 PTSD negatively affects daily activities,1 enjoyment of life,21 and increases the risk of suicidal behaviors.22

This study analyzes a sample of Colombian Caribbean COVID-19 survivors. A high frequency of familism and psychological and financial support from relatives, neighbors, and friends23 characterizes a region of the country. In addition, the relationship between depression risk, insomnia risk, and PTSD-R are explored. Previous studies that simultaneously measured these outcomes have failed to adjust for the possible confounding effect that these variables can generate.7,12,15 Depression and insomnia are part of the symptoms of PTSD diagnosis.1

The study aimed to establish the prevalence and variables associated with PTSD-R in a sample of COVID-19 survivors in Santa Marta, Colombia.

MethodsDesign and sampleA cross-sectional analytical study was designed. There was a convenience sample of COVID-19 survivors who physically or virtually consulted a pulmonology service for symptoms related or not to COVID-19. To establish a prevalence of 25% (±5), with a confidence level of 95%, based on other studies that showed prevalence between 5% and 35%.4–16 A sample of 288 participants had to be completed.24 Likewise, associations with acceptable 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) could be estimated.25

InstrumentsDepression riskDepression risk was assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The tool asks about depressed mood or hopelessness, anhedonia, low level of energy, changes in appetite, low self-esteem, trouble concentrating, changes in moving or speaking, and thoughts about death or hurting. The PHQ-9 quantifies symptoms of depression during the previous two weeks with nine items of four response options, scored from zero to three.26 In the present sample, the PHQ-9 presented Cronbach's alpha of 0.85. For Colombia, ≤7 indicates depression risk, with a sensitivity of 0.90, specificity of 0.82, and Cronbach's alpha of 0.80.27

Insomnia riskInsomnia risk was quantified using the Athens Insomnia Scale (AIS). The scale asks about trouble falling asleep, frequent awakenings, early awakening, duration and quality of sleep, daytime mental and physical functioning and well-being, and sleepiness. The AIS brings together eight items with response options scored from zero to four. Scores of ≤6 risk of insomnia are considered.28 In the present sample, the AIS reached Cronbach's alpha of 0.85. In Colombia, the AIS has shown a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93.29

PTSD-RThe PTSD-R was measured with the SPAN. The SPAN consists of four items investigating physical symptoms by remembering the traumatic event, difficulties feeling happy or sad or happy, irritability or attacks of anger and nervousness. The instrument offers five response options scored from one to five.30 Scores ≥12 were classified as PTSD-R based on a Colombian study that used the same cut-off point. In this research, the SPAN showed Cronbach's alpha of 0.81.31 The SPAN presented Cronbach's alpha of 0.81 in the present sample.

ProcedureThe patients were contacted in the pulmonology outpatient service of three institutions. Patients were informed of the study objectives of giving informed consent. Patients completed the research questionnaire, an online link between October 12, 2020, and April 30, 2021.

Statistical analysisThe descriptive analysis observed frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, and mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for quantitative variables. PTSD-R was considered the dependent variable; the remaining variables were treated as independent variables. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% CI were estimated. Additional log ORs were calculated to avoid overestimation for ORs with a wide 95%CI. This alternative is recommended when the prevalence of the dependent variable is greater than 10%.32

Greenland's recommendations were considered to adjust for significant associations. The first recommendation is to test the effect of all variables that show probability values ≤0.20. The second is to retain the variables that show significant associations during the adjustment process. Furthermore, the third is to leave in the final model the non-significant variables that induce a variation ≥10% in the association that presents the highest OR.33 The final model had to fit adequately, showing a Hosmer–Lemeshow test with a p-value >0.10.34 The analysis was completed in the Project Jamovi 1.6 program.35

Ethical considerationsA research ethics committee approved the study of a Colombian university (Approval Certificate 002 of March 26, 2020). Participants signed informed consent voluntarily and without receiving incentives. The instruments used in the research are free to use. The study followed the Colombian standard in health research36 and the international regulation for the participation of humans in research.37

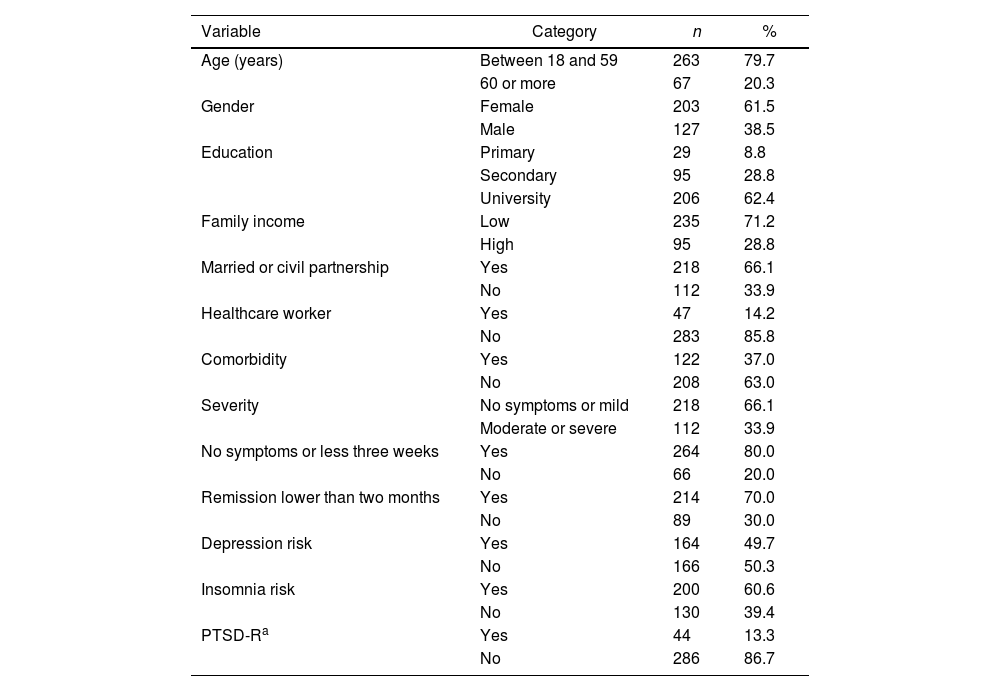

ResultsThree hundred and thirty-three COVID-19 survivors were invited to participate; 2.1% (n=7) rejected the invitation. The 330 participants were between 18 and 89 years old (47.7±515.2), 61.5% were women, 62.4% had university studies, 66.1% were married or union-free, and 71.2% with low family income. The prevalence of depression risk was 49.7%; the risk of insomnia was 60.6%; and PTSD-R was 13.3%. More characteristics of the population are presented in Table 1.

Sample demographic description (N=330).

| Variable | Category | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Between 18 and 59 | 263 | 79.7 |

| 60 or more | 67 | 20.3 | |

| Gender | Female | 203 | 61.5 |

| Male | 127 | 38.5 | |

| Education | Primary | 29 | 8.8 |

| Secondary | 95 | 28.8 | |

| University | 206 | 62.4 | |

| Family income | Low | 235 | 71.2 |

| High | 95 | 28.8 | |

| Married or civil partnership | Yes | 218 | 66.1 |

| No | 112 | 33.9 | |

| Healthcare worker | Yes | 47 | 14.2 |

| No | 283 | 85.8 | |

| Comorbidity | Yes | 122 | 37.0 |

| No | 208 | 63.0 | |

| Severity | No symptoms or mild | 218 | 66.1 |

| Moderate or severe | 112 | 33.9 | |

| No symptoms or less three weeks | Yes | 264 | 80.0 |

| No | 66 | 20.0 | |

| Remission lower than two months | Yes | 214 | 70.0 |

| No | 89 | 30.0 | |

| Depression risk | Yes | 164 | 49.7 |

| No | 166 | 50.3 | |

| Insomnia risk | Yes | 200 | 60.6 |

| No | 130 | 39.4 | |

| PTSD-Ra | Yes | 44 | 13.3 |

| No | 286 | 86.7 |

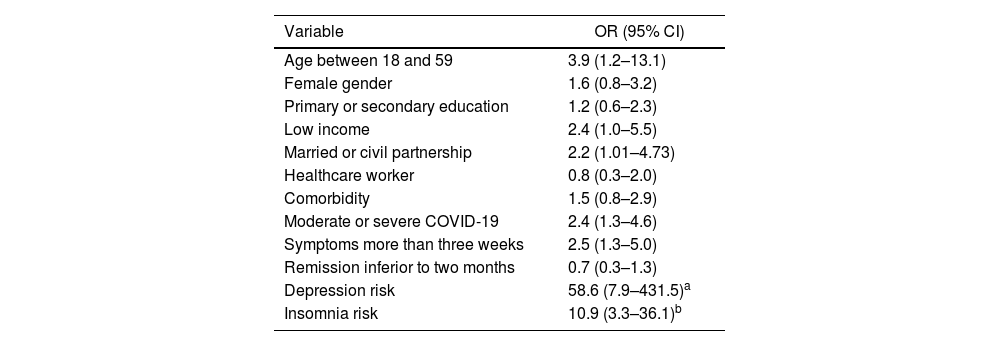

The crude ORs showed a statistically significant association between depression risk, insomnia risk, age under 60 years, low family income, married or living in a free union, moderate or severe infection, symptoms ≤3 weeks, and PTSD-R. See the OR and 95% CI values in Table 2.

Crude association for PTSD-R in COVID-19 survivors.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Age between 18 and 59 | 3.9 (1.2–13.1) |

| Female gender | 1.6 (0.8–3.2) |

| Primary or secondary education | 1.2 (0.6–2.3) |

| Low income | 2.4 (1.0–5.5) |

| Married or civil partnership | 2.2 (1.01–4.73) |

| Healthcare worker | 0.8 (0.3–2.0) |

| Comorbidity | 1.5 (0.8–2.9) |

| Moderate or severe COVID-19 | 2.4 (1.3–4.6) |

| Symptoms more than three weeks | 2.5 (1.3–5.0) |

| Remission inferior to two months | 0.7 (0.3–1.3) |

| Depression risk | 58.6 (7.9–431.5)a |

| Insomnia risk | 10.9 (3.3–36.1)b |

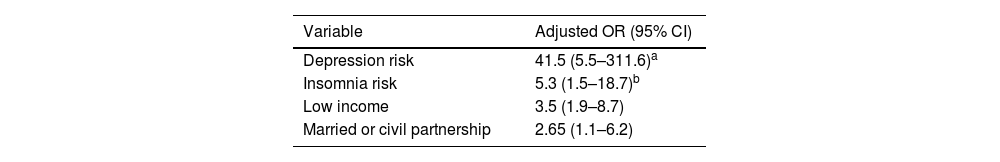

In addition, the gender variable was considered for adjustment, which showed an association with a p-value of 0.19. After adjusting, depression risk, insomnia risk, a low family income, and being married or living in a free union kept the association estimates within the significant range, with adequate goodness of fit (Hosmer–Lemeshow test's chi-squared of 1.35, degrees of freedom of 7 and p-value of 0.99). These variables are presented in Table 3.

DiscussionEven in a cultural context with high familism and social support, 13% of COVID-19 survivors present PTSD-R; the risk is significantly higher in the presence of depression risk, insomnia risk, low family income, and having a stable partner among COVID-19 survivors.

The prevalence of PTSD-R varies widely among COVID-19 survivors. In the present study, it was observed that 13% of the participants are in PTSD-R. This observation is consistent with research conducted in China7 and Italy,6 which showed comparable values between 10% and 12%. However, lower frequencies were observed in survivors in Iran8 and Norway,5 with prevalences between 6% and 8%, and higher in China,4,14 Israel,15 Italy,9,10 Turkey11 and Colombia,12 frequencies between 17% and 35%. Chen et al.13 and Nagarajan et al.14 conducted meta-analytic reviews, agreeing that 16% of surviving COVID-19 patients present PTSD-R. These disparities in the observed prevalence of PTSD-R, even in studies carried out in the same country, can be explained by the characteristics of the population, the sampling design, and the measurement instruments.38

In the present sample of COVID-19 survivors, age and PTSD-R were not observed to be related. This data is consistent with other investigations that showed the frequency of PTSD-R was similar in different age groups.4,6,12 However, other studies have reported that PTSD-R is more prevalent in older ages.7,15

The relationship between gender and PTSD-R among COVID-19 survivors is inconsistent. The present study's finding is consistent with several studies that reported that the prevalence of PTSD is similar in men and women.4,7,8,11,12,16 However, other research has documented that PTSD is usually higher in women than men, similar to what was observed before the COVID pandemic.5,6,9

Among the predisposing factors for PTSD, there are biological and socioeconomic elements. In COVID-19 survivors, the relationship between marital status, family income, and PTSD-R had been scarcely reported. Guillen-Burgos et al.12 found that widowed or separated people showed a greater probability of PTSD-R; however, PTSD-R was more common in low- and high-income survivors than middle-income survivors. It is possible that people in a stable relationship, generally with children and low family income, have a higher PTSD-R. Greater vulnerability to PTSD has been observed in people who simultaneously face various psychosocial stressors.38,39

It is plausible that the characteristics of the COVID-19 infection and treatment circumstances are related to PTSD-R. The current study shows that infection characteristics, healthcare workers, and comorbidity were independent of PTSD-R after adjusting for other variables. This observation is not novel. It has been documented that PTSD is independent of the place of treatment (outpatient or in-hospital),5 the duration of hospitalization for COVID-19,4,12 or the management in the care unit intensive,7,12,15 and discharge time.4 Likewise, contrary to expectations, it has been reported that PTSD may be higher when the hospital stay is shorter and health workers present the same PTSD as the general population.7 However, other researchers have observed that PTSD-R is greater depending on the number and severity of symptoms,5,7,11,12 the longer hospital stay,6,14 comorbidity,6 and persistence of residual symptoms.15

The association between depression, insomnia, and PTSD-R has been little explored in Colombian COVID-19 survivors. In the present investigation, the risk of depression and insomnia showed a strong association with PTSD-R. This finding is consistent with previous studies that showed that symptoms of depression11,16 and manifestations of insomnia were persistent in COVID-19 survivors.11 This observation is consistent with the diagnostic criteria for PTSD that include changes in mood and sleep pattern.1

The variables associated with PTSD-R may vary due to the design of the studies and the social determinants of mental health.40 The risk factors for PTSD converge predisposing or proximal vulnerabilities (genetic and physical factors, lifestyle and social and community networks), intermediate (living and working conditions), and distal (socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental conditions).38,39

Practical implicationsSymptoms of PTSD are common in critically ill survivors, between 15% and 45% of patients in intensive care units six to twelve months after discharge.41 By June 7, 2023, around the world, the COVID-19 pandemic had affected more than 695 million people and 6.9 million deaths.17 This case-fatality rate explains PTSD symptoms among COVID-19 survivors due to fear or imminence of death. Similarly, the last confinement can be configured as a stressor and not necessarily a formal traumatic event.42 In the same way, it is necessary to consider that all psychiatric symptoms may directly result from the neurological damage induced by SARS-CoV-2.43,44

Primary care and mental health professionals are vital in identifying and managing psychological symptoms in COVID-19 survivors.18,19,45 For the diagnosis of PTSD, fear of infection was insufficient; it is always necessary to specify the exposure to one or more events that involved real death threats related to the pandemic.1 Reducing PTSD-R among people diagnosed with COVID-19 is crucial through preventive actions such as first aid and psychological and cognitive-behavioral support for family members, according to particular needs.42

Study strengths and limitationsThis research has the strength of showing the frequency and variables associated with PTSD-R in an adequate sample of COVID-19 survivors in the sociocultural context of the Colombian Caribbean.24,25 However, it has the limitation that the findings cannot be generalized due to non-probabilistic sampling.40 In the same way, the psychological variables were quantified with measurement scales that only screen and can overestimate the prevalence because they only indicate people at high risk of meeting criteria for a formal disorder.41 The diagnosis of a mental disorder is a complex clinical process that considers the presence of symptoms, the deterioration in global functioning or quality of life, and the factors that can explain the clinical manifestations, for example, comorbidity, drug use, substance abuse that induces dependence and normative events such as grief.1

ConclusionsIt is concluded that two out of every fifteen COVID-19 survivors are in PTSD-R. Depression and insomnia risks are strongly associated with PTSD-R among survivors in Santa Marta, Colombia. Research is needed to evaluate the long-term PTSD-R in a probability sample.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

ContributionAdalberto Campo-Arias: participated in the conception and design of the article, statistical analysis, interpretation, and discussion of the results, wrote the draft, and approved the final version.

FundingInstituto de Investigación del Comportamiento Humano, Bogotá, and Universidad del Magdalena, Santa Marta, Colombia.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.