Because the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic fostered an environment marked by limitations for social encounters and emotional fluctuations, it is essential to determine the variations in the consumption of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) and Electronic Non-nicotine Delivery Systems (ENNDS) during this period in young Colombians between 18 and 25 years of age, evaluating the emotional factors that affect the consumption mentioned above and the risky consumption.

MethodsAfter collecting data through a virtual survey, in this cross-sectional study a mainly descriptive analysis of variables related to the consumption of ENDS and ENNDS was carried out in parallel with three different mental health outcomes: depression, anxiety, and loneliness.

ResultsMost participants reported a decrease or cessation of their consumption during the restrictive measures, which is consistent with the fact that more than half said that consumption was limited to social gatherings. Additionally, anxiety and loneliness symptoms are more present in those participants with risky consumption than those who do not.

ConclusionAlthough the consumption of ENDS and ENNDS has a social predominance, there may be factors that modulate it. For this reason, it is essential to deepen research on this topic to propose public health strategies that allow this consumption to be mitigated.

Debido a las limitaciones sociales propiciados por la pandemia por SARS-CoV-2 y las fluctuaciones emocionales asociadas, es esencial determinar las variaciones en el consumo de sistemas electrónicos de administración de nicotina (SEAN) y sistemas electrónicos sin suministro de nicotina (SSSN) durante este periodo en jóvenes colombianos entre 18 y 25 años, evaluando los factores emocionales que afectaron el patrón de consumo y aquel riesgoso.

MétodosDespués de recopilar datos por medio de una encuesta virtual, en este estudio transversal se realizó un análisis principalmente descriptivo de variables relacionadas con el consumo de SEAN y SSSN en paralelo con tres desenlaces de salud mental distintos: depresión, ansiedad y soledad.

ResultadosLa mayoría de los participantes reportó una disminución o cesación de su consumo durante las medidas restrictivas, lo cual es acorde con el hecho de que más de la mitad haya reportado al momento de realizar la encuesta un consumo limitado a las reuniones sociales. Adicionalmente, la sintomatología ansiosa y de soledad está más presente en aquellos participantes con un consumo riesgoso en comparación con aquellos que no lo tienen.

ConclusionesAunque el consumo de SEAN y SSSN tenga un predominio social, puede haber factores que lo modulen. Por ello, es importante ahondar la investigación en este tema para poder plantear estrategias de salud pública que permitan atenuar este consumo.

The consumption of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS) and Electronic Non-nicotine Delivery Systems (ENNDS) is a common habit in young people between 15 and 24 years old,1 which is in part determined by a social component, since it increases in social gatherings and parties. As a result, its use has risen considerably in youth since 2011, despite achieving a five-fold decrease in tobacco use.2,3

This increase is associated with the inclusion of a variety of flavours on the devices, and due to their use in some tobacco cessation programmes, ENDS and ENNDS are perceived as less harmful, less addictive, and have better social acceptance, creating a false sense of safety.4–6 However, the use of ENDS at an early age has been associated with a higher prevalence of use of other drugs of abuse (DOB),3 alterations in the development of the brain structure and its signalling mechanisms,7 behavioural disturbances,7,8 and mental disorders.9

On the other hand, the recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic affected the environment where these devices find common usage because social activities involving a conglomeration of people were cancelled from March 25 to August 31, 2020, due to the imposition of mandatory preventive isolation in Colombia. Between the end of the general quarantine and mid-2021, night and frequent curfews and sectorized quarantines were decreed in different cities nationwide. Then, the economic reactivation began, where some strict confinement measures were lifted and replaced by restrictive measures in recreational spaces, work, and study.

Globally, these isolation measures have been associated with short and long-term impacts on mental health,10,11 such as increased stress, anxiety, and affective disorders such as depression.12 Likewise, it impacts the pattern of substance use; for example, it is associated with increased alcohol consumption and decreased cigarette and electronic cigarette use.10 Particularly in young people, there is a decrease in consumption, which coincides with adolescents’ substance use theories that mention that social restrictions entail less social pressure and fewer rewards when exploring their use.13

Since the pandemic started, some studies have reported changes in the consumption patterns of ENDS and ENNDS. There have been suggested as alleviating factors the limitation of social encounters, the risk perception about health outcomes due to SARS-CoV-2,14,15 and the return to non-independent homes.16 On the other hand, as a factor that augments consumption, there have been proposed elements associated with stress produced by the pandemic,16 staying in places where consumption is allowed, boredom, having more free time,17 and experiencing stress and anxiety.18

There is a gap in the knowledge about the factors associated with ENDS and ENNDS consumption, especially related to the exacerbation of emotional symptoms during the pandemic and changes in consumption patterns. Therefore, this study intended to determine the variations in the consumption of ENDS and ENNDS during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and its control measures in young Colombians between 18 and 25 years and the emotional factors that may affect their consumption.

Materials and methodsStudy designWe carried out a cross-sectional study through electronic surveys. The research protocol was approved by the Research and Institutional Ethics Committee of the San Ignacio University Hospital and the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Act No. 12/2021. Everyone must consent to participate.

PopulationWe performed a non-probabilistic convenience and snowball sampling. The survey was disseminated through email and social networks, where the possible participant was directed to the survey. One hundred forty-two people accessed the link between July and August 2021. The inclusion criteria were being residents of Colombia, reporting consumption of ENDS or ENNDS at least once in the last two years and being between 18 and 25 years old.

Study variablesWe collected data through REDCap.19 The demographic variables investigated were age, gender, and occupation. Regarding consumption, we inquired about nicotine in the devices to differentiate between ENDS and ENNDS, the type of device, use by peers, self-perception of the risk that consumption represented for their health, and the frequency of consumption. We also asked about the change in consumption during the restrictive measures and their direction.

To determine the risky consumption of ENDS and ENNDS at the time of the survey, we used an adaptation of the Cut, Annoyed, Guilty, Eye-Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID) scale,20 using the 75th percentile of the results as the cut-off point since there is no established point for the consumption of ENDS and ENNDS.

Regarding mental health outcomes, three instruments were used: The Three-Item-Loneliness scale21 to measure the risk of loneliness with a cut-off point of 3 points, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale-7 (GAD-7) 22 for generalized anxiety, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) 23 for symptoms of depression. We used cut-off points of 7 and 10 points, respectively. These three scales were filled in according to the symptoms presented the days before completing the survey. If positive, at the end of the survey, the participants received an invitation to seek professional support on the district lines for Bogotá D.C. or at a national level and with the ‘Mentes Colectivas’ group of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. In addition, at the end of filling out the form, the participant received feedback on how to take care of mental health in the pandemic and physical distancing.

Statistical analysisGiven the quantitative nature of the variables, we performed a descriptive analysis of each of these to explore the distribution of the population and its descriptive statistics using the R studio programme.24 With this information, we did an exploratory analysis to identify missing data, and complete cases were included in the analysis concerning the neuropsychiatric measures assessed.

Subsequently, we calculated the prevalence ratio of the risk of abusive or dependent use of ENDS or ENNDS, as well as the prevalence ratio for generalized anxiety, depression, and loneliness symptoms, between subjects with and without risky use of ENDS and ENNDS.

Additionally, to estimate the association of the mental health variables, we made different logit models taking the positive for mental health symptoms as dependent variables and age, gender, occupation, presence of nicotine in the device, most frequently used device type and DOB consumption as independent variables.

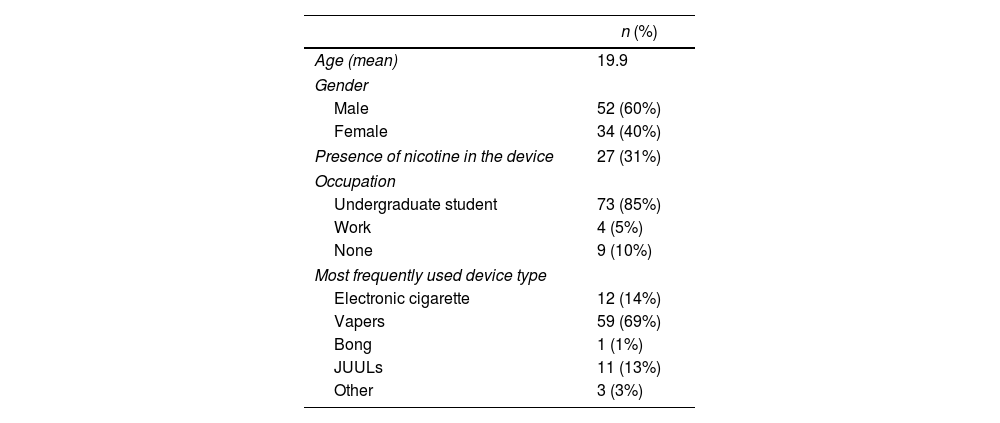

ResultsSociodemographic elementsThe survey was completed by 86 participants who met the inclusion criteria. Their characteristics are described in Table 1. The mean age of the sample was 19.9 (SD=3.57), with 60% (n=52) of the population being male. According to the inclusion criteria, all participants had used any ENDS or ENNDS in the last two years at least once, 31% (n=27) of them a user of ENDS. Also, 94% (n=81) subjects reported the use of these devices by their peers.

Population characteristics.

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age (mean) | 19.9 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 52 (60%) |

| Female | 34 (40%) |

| Presence of nicotine in the device | 27 (31%) |

| Occupation | |

| Undergraduate student | 73 (85%) |

| Work | 4 (5%) |

| None | 9 (10%) |

| Most frequently used device type | |

| Electronic cigarette | 12 (14%) |

| Vapers | 59 (69%) |

| Bong | 1 (1%) |

| JUULs | 11 (13%) |

| Other | 3 (3%) |

11% (n=10) of participants did not report a difference in their consumption. 45% (n=39) of them reported a decrease in consumption, with the most part (29%, n=25) reporting a total cessation. Conversely, 43% (n=37) of participants reported increased consumption during restrictive measures.

Regarding consumption at the time of the survey, 20% (n=17) reported not using ENDS or ENNDS. However, 6% (n=5) had a weekly consumption, 8% (n=7) a nearly daily consumption, and 15% (n=13) a daily consumption. On the other hand, 51% (n=44) of participants reported consumption exclusively done in social gatherings.

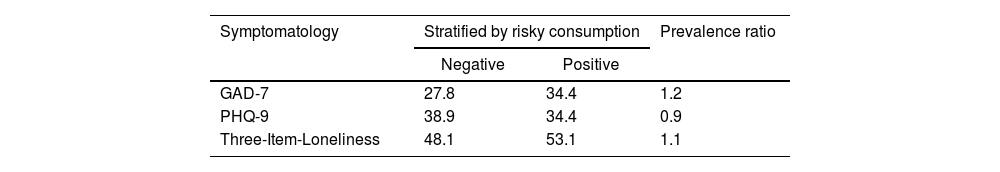

Risky consumption of ENDS and ENNDS and its association with mental health outcomesAccording to CAGE-AID battery, people with a risky consumption, corresponds to 37% (n=32). The prevalence of anxious symptoms was 26% (n=22), for depressive symptoms was 32% (n=28), and loneliness perception was 50% (n=43). As presented in Table 2, when comparing these results with risky consumption of ENDS or ENNDS, we found that individuals with this outcome showed 1.2 times more anxious symptoms, 1.1 times more self-perception of loneliness, but 0.9 times fewer depressive symptoms.

Prevalence ratios for positive GAD-7, PHQ-9, and Three-Item-Loneliness scores stratified by risky consumption of ENDS and ENNDS.

| Symptomatology | Stratified by risky consumption | Prevalence ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative | Positive | ||

| GAD-7 | 27.8 | 34.4 | 1.2 |

| PHQ-9 | 38.9 | 34.4 | 0.9 |

| Three-Item-Loneliness | 48.1 | 53.1 | 1.1 |

GAD-7: General Anxiety Disorder-7; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; ENDS: Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems; ENNDS: Electronic Non-nicotine Delivery Systems.

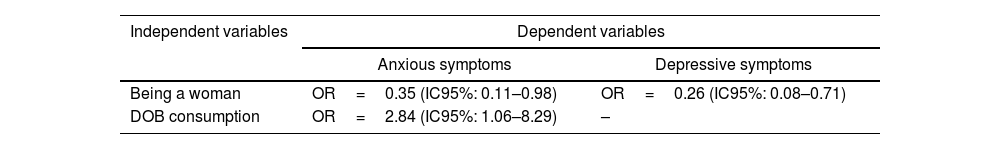

Using logit models, we found a positive association between presenting anxious symptoms and DOB consumption, and a negative association with being a woman. Regarding depressive symptoms, we only found a negative association with being a woman, while with loneliness self-perception, no statically significant association was found (Table 3).

Odds ratio for the association of mental health outcomes with sociodemographic elements.

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | |

|---|---|---|

| Anxious symptoms | Depressive symptoms | |

| Being a woman | OR=0.35 (IC95%: 0.11–0.98) | OR=0.26 (IC95%: 0.08–0.71) |

| DOB consumption | OR=2.84 (IC95%: 1.06–8.29) | – |

Analysis was corrected for age, gender, occupation, presence of nicotine in the device, most frequently used device type and DOB consumption. DOB: drugs of abuse; OR: odds ratio.

In this study, we evaluated the self-perception of changes in ENDS and ENNDS consumption in young Colombians during restrictive measures imposed during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and the consumption that can be classified as risky or risky not, and its association with multiple mental health variables. Our findings point to a decrease in the consumption of these devices during the pandemic period, which strengthens the hypothesis of the social component as a risk factor for consumption.5 This differs from other substances like heroin, opiates, or marijuana, where consumption increased during the lockdown period.25 It's worth highlighting the case of the rise in alcohol consumption, having as a cause, according to a study done in the first year of the pandemic in the United States, more stress, more availability, and more boredom, as self-reported by participants.26

The decrease in ENDS and ENNDS consumption is consistent with the literature,27 where is reported that 44.7% of Canadian adolescents and adults decreased their e-cigarette frequency of consumption in 2020. A similar situation was reported in the United States, where most adolescents and adults reported a change in their consumption, mainly reporting a decrease.28 However, in the present study, a considerable part of the population where consumption increased was also identified (43%). Although the causality of this finding cannot be established, it could be explained by the emotional fluctuations and stressors associated with the pandemic.16,18

Furthermore, in our study population, we found that 37% presented a risky consumption of these devices. This was positively associated with symptoms of anxiety and loneliness, even if we can’t confirm that this is due to ENDS and ENNDS’ use or to a case of reverse causality, where consumption increased due to the presence of previously mentioned symptomatology.29 Also, considering risky consumption prevalence and ENDS could cause most young adults’ exposure to nicotine, this device could trigger additional cigarette consumption.

Regarding loneliness perception, we could not find information about consumption during and after quarantine. Nevertheless, a positive association has been described between loneliness and smoking.30 It has been hypothesized that e-cigarette use in young people is highly influenced by feelings of loneliness and social pressure. It is a means to maintain social status and achieve social acceptance, especially in those young people with a perception of loneliness.31 However, this does not explain the positive association found in our study. During restrictive measures, adolescents were not participating in social events that created the need for social acceptance, thus mitigating the perception of loneliness.

In contrast, the presence of depressive symptoms was negatively associated with risky consumption, which was not consistent with results from other studies where a positive and bidirectional relation between these two variables was found.32 For example, a study on adolescents found that depression was associated with increased frequency of use of these devices.29

On the other hand, most participants in our study reported using ENNDS over ENDS, which could indicate a consumption triggered by social elements like gatherings or the flavour of these devices, the latter being desirable to the user.5 Nevertheless, given that a study published in 2017 in the United States found that about 99% of devices in the market contain some amount of nicotine,33 the number of people using ENDS could be more significant than we found, which could present a more substantial threat for public health.

Finally, we found a positive association between DOB consumption and anxiety symptoms related to sociodemographic variables reported in the literature.34 Also, we found a negative association between being a woman and having anxious or depressive symptoms. Nonetheless, the association should be studied in a broader sample.

In addition, the present study has some limitations. First, we included a population of 18 years or older, even if consumption at an earlier age has been reported recently.2 This justifies the conduction of a future study that includes younger people. Second, surveying the initial restrictive measures may have generated a recall bias. Nevertheless, taking this into account, we only asked for the direction, not the magnitude of consumption change, facilitating remembrance. Third, due to the methodology used, we cannot find causality in the shift in consumption. Still, we can point to factors that may be the gateway to implementing mechanisms that aim to reduce consumption from a public health standpoint. Finally, we did not use a validated test battery for risky consumption of ENDS or ENNDS. Given that there is no literature on this matter, we defined the cut-off point according to a measure of relative standing since physiological mechanisms of consumption, dependence, and abstinence of these devices are different from alcohol mechanisms, which prevents the use of the same cut-off point of the CAGE-AID screening tool.

In contrast, among the strengths of this study is the fact that we successfully identified consumers and associated factors, this being potentially helpful for reducing the mentioned health risks in the short and long term. Moreover, it is not frequent to associate mental health outcomes with risky consumption in the literature, giving novelty to our results. Also, when users answered the survey, they received information about their mental health symptoms and how to take care of them. Furthermore, when users completed the survey, they received information about ENDS and ENNDS cessation. Lastly, in Latin America, we scarcely found any study that evaluated these associations, making this work one of the few to explore consumption patterns in this context.

Finally, even if the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic it's not a public health emergency anymore, ENDS and ENNDS consumptions continue as a public health problem. Therefore, some governments are applying bans and taxes on these products, but the policies applied keep a high level of heterogeneity.35

ConclusionsOur results indicate a decrease in the consumption of ENDS and ENNDS during the restrictive measures due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and most participants reported using these devices with their peers. On the other hand, a third of the population said risky to use and associated with a higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms and perceived loneliness. Nevertheless, we consider that additional studies are necessary for a better understanding of consumption patterns of ENDS and ENNDS and the related factors in the young population to propose campaigns for the cessation of these devices.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

This work was presented in ‘III Encuentro de Semilleros de Investigación e Innovación en Salud’ on 7/10/2021. Hosted by Medicine Faculty, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia.