To describe the impact of COVID-19 on oncology care providers’ self-reported perceived stress, resilience, moral distress, anxiety, and depression in Colombia.

MethodsDuring 2020, a cross-sectional survey was carried out among oncology care providers. The Perceived Stress Scale, Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale, Moral Distress Thermometer, and the PHQ-4 were used. Basic socio-demographic and occupational characteristics are described, and bivariate and multivariate analyses were done to investigate their association with a high PHQ-4 score (>6).

Results148 participants (mean age 43.1 years, 54.6% women, 72.3% medical specialists) were recruited. The major source of stress was not being infected, but spreading COVID-19. A low prevalence of depression/anxiety was found, as well as low resilience and moral distress. Women reported lower resilience and higher depression/anxiety. History of depression and lack of adequate coping strategies were associated with higher levels of depression/anxiety.

ConclusionsThe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of oncology care providers was mild, probably due to the protection for oncology patients during this period; however, women reported a greater impact. The association of demographic and clinical variables with higher levels of depression/anxiety should inform further preventive measures to reduce the impact of prolonged public health crises on healthcare providers’ mental health.

Describir el impacto del COVID-19 en el estrés, la resiliencia, el sufrimiento moral, la ansiedad y la depresión percibidos por los proveedores de atención oncológica en Colombia.

MétodosDurante el año 2020 se realizó una encuesta entre prestadores de atención oncológica. Se utilizaron la escala de estrés percibido, la escala de resiliencia de Connor-Davidson, el termómetro de angustia moral y el PHQ-4. Se describen las características sociodemográficas y ocupacionales básicas, y se realizaron análisis bivariados y multivariados para investigar su asociación con una puntuación alta de PHQ-4 (>6).

ResultadosSe reclutaron 148 participantes (edad media 43.1 años, el 54.6% mujeres y el 72.3% médicos especialistas). La principal fuente de estrés no era estar infectado, sino propagar el COVID-19. Se encontró baja prevalencia de depresión/ansiedad, baja resiliencia y angustia moral. Las mujeres reportaron menor resiliencia y mayor depresión/ansiedad. Los antecedentes de depresión y la falta de estrategias de afrontamiento adecuadas se asociaron con niveles más altos de depresión/ansiedad.

ConclusionesEl impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 en la salud mental de los proveedores de atención oncológica fue leve, probablemente debido a la protección de los pacientes oncológicos durante este período; sin embargo, las mujeres reportaron un mayor impacto. La asociación de variables demográficas y clínicas con niveles más altos de depresión/ansiedad debería reportar medidas preventivas adicionales para reducir el impacto de las crisis de salud pública prolongadas en la salud mental de los proveedores de atención médica.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare providers experienced several unexpected stressors due to the threat to quality of care by challenges, such as the inability to provide usual standards, the abrupt implementation of new guidelines, the uncertainty about the safety and efficacy of remote care for patients frequently isolated, and fears of acquired infection and infecting their families.

Some studies have found that the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with significant long-term stress, but not mental illness in healthcare providers.1 Other studies found that hospital workers treating SARS-Cov2-infected patients reported significantly higher levels of burnout and psychological distress. Consequently, these hospital workers reduced patient contact and work hours quicker.2

In the oncology care setting, additional stressors include competing demand for resources with COVID-19 care, the high mortality rate among oncology patients with COVID-19,3 and balancing the risks of SARS-Cov2 infection against the benefits of cancer therapies that might compromise patient immunity or cause illness due to exposure to the hospital environment. Furthermore, oncology care providers were under the same everyday stressors as the general population, including providing child and elderly care, insufficient family and leisure activities outside the home, and social isolation.

How oncology providers face these challenges varies broadly according to factors such as their primary role in oncology care and the type of practice. Several studies have reported the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the wellbeing and mental health of radiation oncologists, haemato-oncologists, oncology surgeons, oncology nurses, radiotherapists, and other workers in the oncology healthcare team4–9; however, the response to stress also depends on the context, including general socioeconomic conditions and characteristics of the health systems. Despite potential differences among countries, given their unique contextual characteristics, most studies have been conducted in high-income countries. To our knowledge, only Brazil has been included in an international survey on anxiety among oncologists due to the pandemic and we also found only one publication (also in Brazil) about the psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on oncology nursing.10

Our study aimed at quantifying and describing the impact of COVID-19 on oncology care providers as levels of perceived stress, resilience, moral distress, anxiety, and depression in Colombia, a middle-income country in South America with universal health insurance coverage.

MethodsThe first COVID-19 case was reported in Colombia during late March 2020. The lockdown started on March 27th and lasted until August 30th after the end of the first pandemic wave. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of oncology care providers, including medical specialists, nurses, and psychologists. Between May and November 2020, an online questionnaire was distributed among affiliates to the following scientific societies: Haemato-Oncology (ACHO), Radiation Oncology (ACRO), Palliative Care (ASOCUPAC), Oncology Nursing (AEOC), and Oncology and Palliative Care (REPSOCUP).

Four key dimensions of mental health were selected for assessment with the following brief inventory strategies: Perceived Stress Scale (PSS),11 Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CDRS),12 Moral Distress Thermometer (MDT),13 and the four-item Patient Health Questionnaire for Anxiety and Depression (PHQ-4).14 The internal consistency of PSS, CDRS, and PHQ-4 was evaluated by McDonald's-omega (ω) and Cronbach's-alpha (α) indices. In addition, a correlation analysis between scales was carried out using Spearman's rank order test with a 0.01 significance level.

The only exclusion criterion was having worked for less than a year in oncology care. For the study, the measurement instruments were translated into Spanish with a contrast back translation to English to verify the fidelity of the content and ensure its understandability. This study was presented and approved by the ethics committee of the University Hospital San Ignacio (FM-CIE-0471-20).

Data analysisThe data were analyzed using SPSS 24. Stress, resilience, moral distress, anxiety, and depression were managed as separate outcome variables, and their association with socio-demographic characteristics and working conditions was assessed.

For the PSS, each of the four stress sources was rated on a 5-point Likert scale to measure the responses. The median score on each scale item was determined independently. Additionally, a total score was determined in the range of 0–40, in which a higher score indicates a higher stress level.11

For the CDRS, a global score was calculated from a range of 0 to 40, with scores near 40 representing higher resilience levels and scores equal to or below 29 interpreted as low.15 A point scale from 0 to 10 was used for the MDT; scores equal to or higher than 4 were considered high.16 The PHQ-4 scores are operationally categorized as low (scores 0–2), mild (scores 3–5), moderate (scores 6–8), and severe (scores 9–12).14

Frequencies and proportions were estimated to describe socio-demographic and baseline occupational characteristics. Description of outcomes as categorical variables was done by type of care provider (nurse, medical specialist, psychologist), time in oncology care (working experience in years), city of practice (Bogotá and others), and type of center (comprehensive and non-comprehensive). The Shapiro–Wilk normality test was used to analyze the distribution, and the Kruskal–Wallis test was used for comparisons if the abnormal distribution was present, defining a significance cut-off value of 0.05. The McDonald's-ω and Cronbach's-α indices were calculated as internal consistency and reliability estimates.

In addition to the comparisons by categories, as previously described, a measure of binary association for the PHQ-4 and socio-demographic characteristics was done by estimating the OR and a multivariate logistic regression model (enter method) adjusted binary associations if potential variables in the univariate analysis revealed a p-value<0.2.

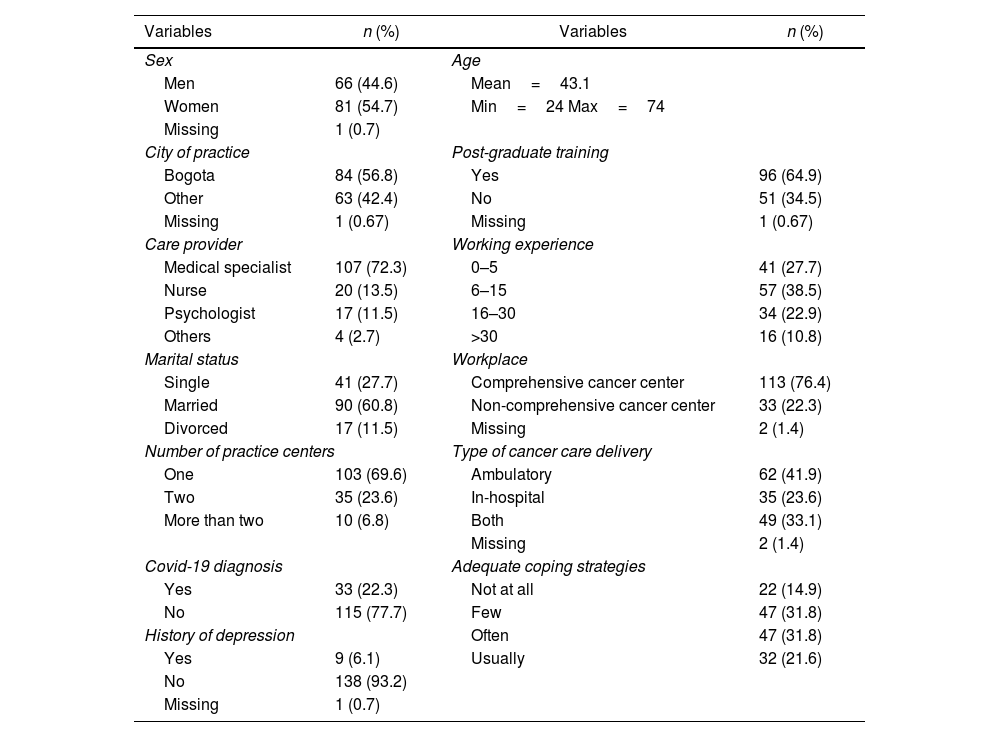

ResultsIn total, 148 health professionals answered the survey, the majority corresponding to medical specialists (72.3%) without significant differences by sex. The mean age was 43.1 years, and most respondents were from Bogotá (56.8%) (Table 1).

Socio-demographic and baseline occupational characteristics.

| Variables | n (%) | Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Age | ||

| Men | 66 (44.6) | Mean=43.1 | |

| Women | 81 (54.7) | Min=24 Max=74 | |

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | ||

| City of practice | Post-graduate training | ||

| Bogota | 84 (56.8) | Yes | 96 (64.9) |

| Other | 63 (42.4) | No | 51 (34.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.67) | Missing | 1 (0.67) |

| Care provider | Working experience | ||

| Medical specialist | 107 (72.3) | 0–5 | 41 (27.7) |

| Nurse | 20 (13.5) | 6–15 | 57 (38.5) |

| Psychologist | 17 (11.5) | 16–30 | 34 (22.9) |

| Others | 4 (2.7) | >30 | 16 (10.8) |

| Marital status | Workplace | ||

| Single | 41 (27.7) | Comprehensive cancer center | 113 (76.4) |

| Married | 90 (60.8) | Non-comprehensive cancer center | 33 (22.3) |

| Divorced | 17 (11.5) | Missing | 2 (1.4) |

| Number of practice centers | Type of cancer care delivery | ||

| One | 103 (69.6) | Ambulatory | 62 (41.9) |

| Two | 35 (23.6) | In-hospital | 35 (23.6) |

| More than two | 10 (6.8) | Both | 49 (33.1) |

| Missing | 2 (1.4) | ||

| Covid-19 diagnosis | Adequate coping strategies | ||

| Yes | 33 (22.3) | Not at all | 22 (14.9) |

| No | 115 (77.7) | Few | 47 (31.8) |

| History of depression | Often | 47 (31.8) | |

| Yes | 9 (6.1) | Usually | 32 (21.6) |

| No | 138 (93.2) | ||

| Missing | 1 (0.7) | ||

The results of the Shapiro–Wilk normality test showed that the PSS, CDRS, MDT, and PHQ-4 variables had an abnormal distribution (p<0.05). Consequently, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used to establish comparisons between the psychological variables and the socio-demographic variables.

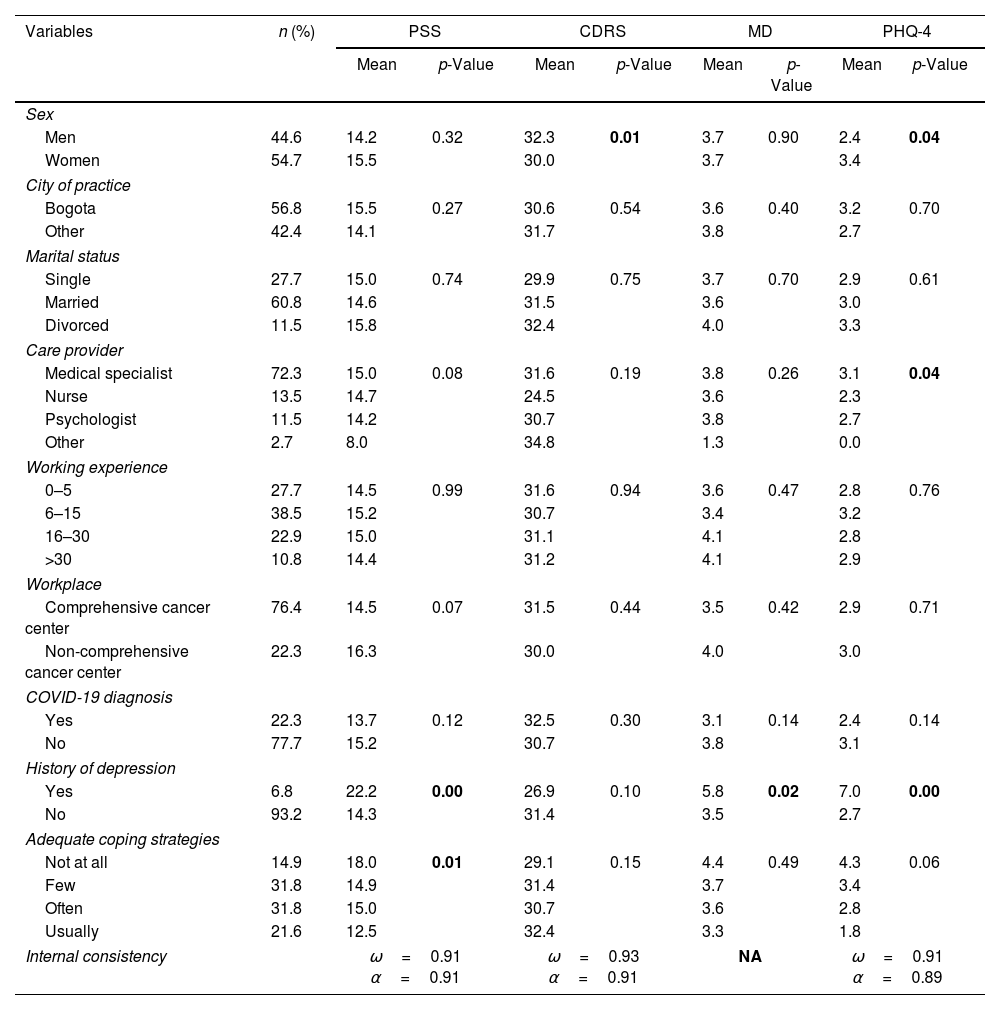

There was a moderate level of perceived stress with average values ranging from 14 to 16 among socio-demographic and occupational characteristics (Table 2), the exception being 12.5 (low level of stress) for care providers, as they usually have adequate coping strategies. Care providers also reported the highest resilience (CDRS) score (32.4) among the defined categories. However, care providers other than physicians, nurses, or psychologists reported the lowest PSS and MDT scores and the highest resilience (CDRS) score.

Average PSS, CDRS, and PHQ-4 scores compared to baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Variables | n (%) | PSS | CDRS | MD | PHQ-4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | p-Value | Mean | p-Value | Mean | p-Value | Mean | p-Value | ||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Men | 44.6 | 14.2 | 0.32 | 32.3 | 0.01 | 3.7 | 0.90 | 2.4 | 0.04 |

| Women | 54.7 | 15.5 | 30.0 | 3.7 | 3.4 | ||||

| City of practice | |||||||||

| Bogota | 56.8 | 15.5 | 0.27 | 30.6 | 0.54 | 3.6 | 0.40 | 3.2 | 0.70 |

| Other | 42.4 | 14.1 | 31.7 | 3.8 | 2.7 | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | 27.7 | 15.0 | 0.74 | 29.9 | 0.75 | 3.7 | 0.70 | 2.9 | 0.61 |

| Married | 60.8 | 14.6 | 31.5 | 3.6 | 3.0 | ||||

| Divorced | 11.5 | 15.8 | 32.4 | 4.0 | 3.3 | ||||

| Care provider | |||||||||

| Medical specialist | 72.3 | 15.0 | 0.08 | 31.6 | 0.19 | 3.8 | 0.26 | 3.1 | 0.04 |

| Nurse | 13.5 | 14.7 | 24.5 | 3.6 | 2.3 | ||||

| Psychologist | 11.5 | 14.2 | 30.7 | 3.8 | 2.7 | ||||

| Other | 2.7 | 8.0 | 34.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | ||||

| Working experience | |||||||||

| 0–5 | 27.7 | 14.5 | 0.99 | 31.6 | 0.94 | 3.6 | 0.47 | 2.8 | 0.76 |

| 6–15 | 38.5 | 15.2 | 30.7 | 3.4 | 3.2 | ||||

| 16–30 | 22.9 | 15.0 | 31.1 | 4.1 | 2.8 | ||||

| >30 | 10.8 | 14.4 | 31.2 | 4.1 | 2.9 | ||||

| Workplace | |||||||||

| Comprehensive cancer center | 76.4 | 14.5 | 0.07 | 31.5 | 0.44 | 3.5 | 0.42 | 2.9 | 0.71 |

| Non-comprehensive cancer center | 22.3 | 16.3 | 30.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | ||||

| COVID-19 diagnosis | |||||||||

| Yes | 22.3 | 13.7 | 0.12 | 32.5 | 0.30 | 3.1 | 0.14 | 2.4 | 0.14 |

| No | 77.7 | 15.2 | 30.7 | 3.8 | 3.1 | ||||

| History of depression | |||||||||

| Yes | 6.8 | 22.2 | 0.00 | 26.9 | 0.10 | 5.8 | 0.02 | 7.0 | 0.00 |

| No | 93.2 | 14.3 | 31.4 | 3.5 | 2.7 | ||||

| Adequate coping strategies | |||||||||

| Not at all | 14.9 | 18.0 | 0.01 | 29.1 | 0.15 | 4.4 | 0.49 | 4.3 | 0.06 |

| Few | 31.8 | 14.9 | 31.4 | 3.7 | 3.4 | ||||

| Often | 31.8 | 15.0 | 30.7 | 3.6 | 2.8 | ||||

| Usually | 21.6 | 12.5 | 32.4 | 3.3 | 1.8 | ||||

| Internal consistency | ω=0.91 α=0.91 | ω=0.93 α=0.91 | NA | ω=0.91 α=0.89 | |||||

Note: PSS=Perceived Stress Scale: scores≥27 are considered high, CDRS=The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale: scores≤29 are considered low, MD=Moral Distress Thermometer: scores≥4 are considered high, PHQ-4=Anxiety and Depression Screen: scores≥9 are interpreted as high or severe, ω=McDonald's-omega, α=Cronbach's-alpha.

Bold letters indicate a significant p value.

Regarding resilience (CDRS), nurses reported the lowest score (24.5), but significant differences were found between men and women (Table 2). However, we found no significant differences between socio-demographic and occupational characteristics, although providers reported not having any adequate coping strategy, and those with 16 or more years of experience reported an MDT score over 4. Concerning the PHQ-4, all categories showed normal to low anxiety–depression levels (scores under 6).

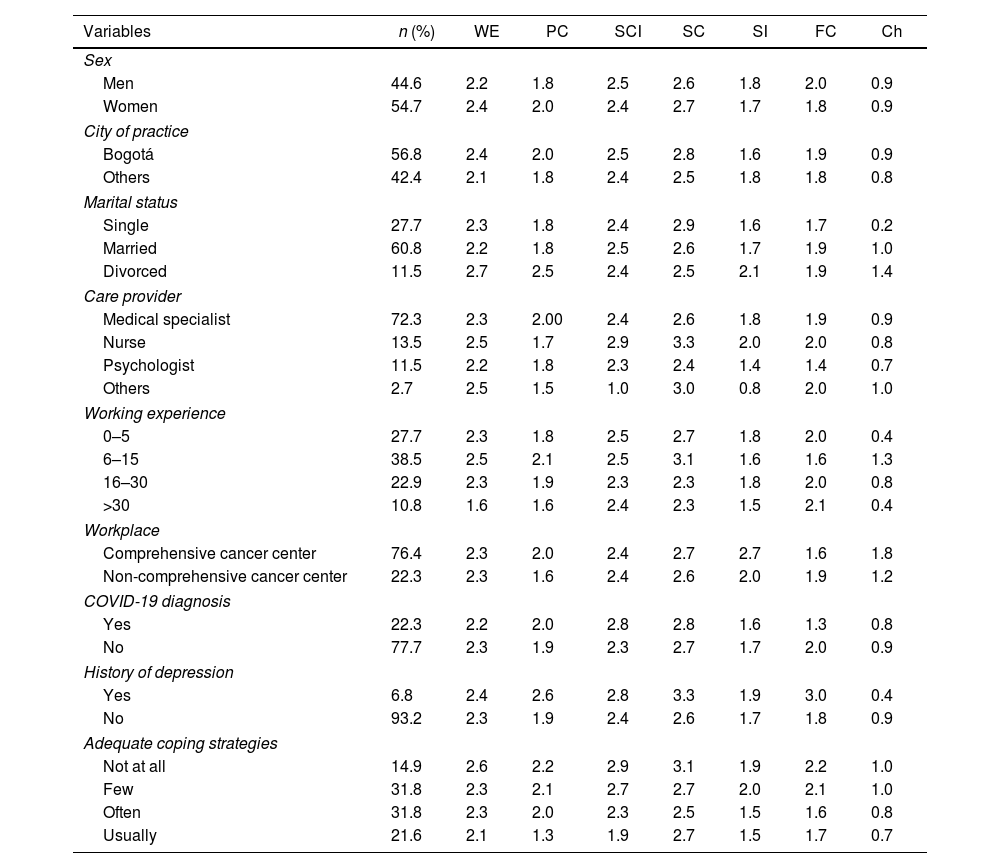

The major stressor was the risk of spreading COVID-19; however, for care providers with working experience between 16 and 30 years and 30 years and over, the major stressors were the working environment and the risk of SARS-Cov2 infection, respectively (Table 3). In all cases, the source of stress with the lowest score was having children at home. Internal consistency indices for this scale were ω=0.79 and α=0.69, thus showing good reliability.

Perceived sources of stress during the COVID-19 pandemic.

| Variables | n (%) | WE | PC | SCI | SC | SI | FC | Ch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||||

| Men | 44.6 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| Women | 54.7 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| City of practice | ||||||||

| Bogotá | 56.8 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Others | 42.4 | 2.1 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 0.8 |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single | 27.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 |

| Married | 60.8 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 1.0 |

| Divorced | 11.5 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 1.9 | 1.4 |

| Care provider | ||||||||

| Medical specialist | 72.3 | 2.3 | 2.00 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 0.9 |

| Nurse | 13.5 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| Psychologist | 11.5 | 2.2 | 1.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| Others | 2.7 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 2.0 | 1.0 |

| Working experience | ||||||||

| 0–5 | 27.7 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 2.7 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.4 |

| 6–15 | 38.5 | 2.5 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 3.1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.3 |

| 16–30 | 22.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 0.8 |

| >30 | 10.8 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.4 |

| Workplace | ||||||||

| Comprehensive cancer center | 76.4 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Non-comprehensive cancer center | 22.3 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.0 | 1.9 | 1.2 |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | ||||||||

| Yes | 22.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.8 |

| No | 77.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 0.9 |

| History of depression | ||||||||

| Yes | 6.8 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 1.9 | 3.0 | 0.4 |

| No | 93.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.9 |

| Adequate coping strategies | ||||||||

| Not at all | 14.9 | 2.6 | 2.2 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.0 |

| Few | 31.8 | 2.3 | 2.1 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 2.1 | 1.0 |

| Often | 31.8 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 0.8 |

| Usually | 21.6 | 2.1 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 0.7 |

WE=working environment, PC=patient care, SCI=SARS-Cov2 infection, SC=spreading COVID-19, SI=social isolation, FC=financial concerns, Ch=having children at home. The underlined numbers are the highest outcomes of every socio-demographic characteristic.

Correlations between all scales were statistically significant (Supplementary Table 2), and all measures revealed optimal reliability (indices>0.80); yet, no measure of internal consistency was done for MDT given the single measure (moral distress) of this scale.

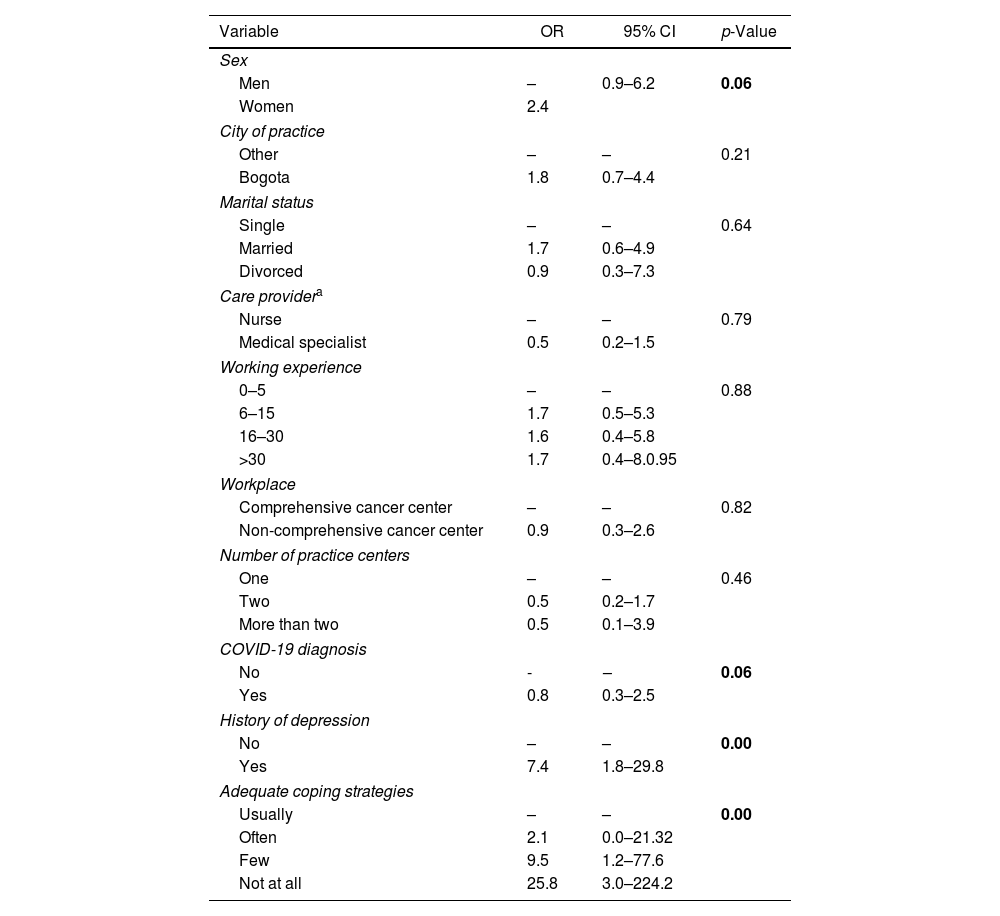

In the bivariate analysis sex, COVID-19 diagnosis, history of depression, and adequate coping strategies showed a p-value<0.2 and were included in the multivariate analysis (Table 4). Only a history of depression showed a significant direct association with high PHQ-4 scores (score≥6, OR 7.4, 95% CI 1.8–29.8), and the perception of adequate coping strategies showed a significant inverse association (Table 4).

Bivariate analysis of the association between high PHQ-4 score (≥6) and baseline characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Men | – | 0.9–6.2 | 0.06 |

| Women | 2.4 | ||

| City of practice | |||

| Other | – | – | 0.21 |

| Bogota | 1.8 | 0.7–4.4 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Single | – | – | 0.64 |

| Married | 1.7 | 0.6–4.9 | |

| Divorced | 0.9 | 0.3–7.3 | |

| Care providera | |||

| Nurse | – | – | 0.79 |

| Medical specialist | 0.5 | 0.2–1.5 | |

| Working experience | |||

| 0–5 | – | – | 0.88 |

| 6–15 | 1.7 | 0.5–5.3 | |

| 16–30 | 1.6 | 0.4–5.8 | |

| >30 | 1.7 | 0.4–8.0.95 | |

| Workplace | |||

| Comprehensive cancer center | – | – | 0.82 |

| Non-comprehensive cancer center | 0.9 | 0.3–2.6 | |

| Number of practice centers | |||

| One | – | – | 0.46 |

| Two | 0.5 | 0.2–1.7 | |

| More than two | 0.5 | 0.1–3.9 | |

| COVID-19 diagnosis | |||

| No | - | – | 0.06 |

| Yes | 0.8 | 0.3–2.5 | |

| History of depression | |||

| No | – | – | 0.00 |

| Yes | 7.4 | 1.8–29.8 | |

| Adequate coping strategies | |||

| Usually | – | – | 0.00 |

| Often | 2.1 | 0.0–21.32 | |

| Few | 9.5 | 1.2–77.6 | |

| Not at all | 25.8 | 3.0–224.2 | |

Note: OR=odd ratio, CI=confidence intervals.

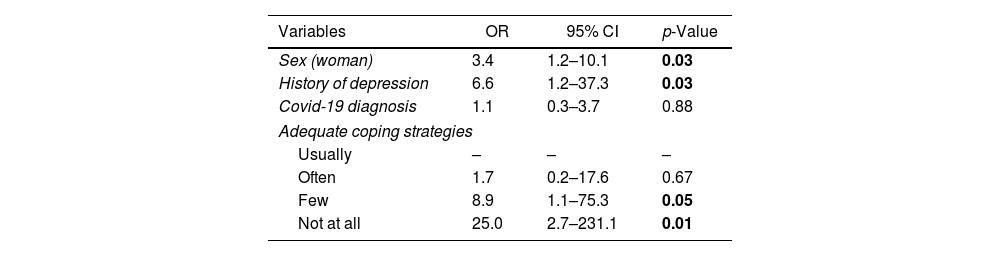

In the multivariate model, only sex (woman), history of depression, and having few or no adequate coping strategies were significantly associated with a high PHQ-4 score (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis of the predictor variables for a high PHQ-4 score (≥6).

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (woman) | 3.4 | 1.2–10.1 | 0.03 |

| History of depression | 6.6 | 1.2–37.3 | 0.03 |

| Covid-19 diagnosis | 1.1 | 0.3–3.7 | 0.88 |

| Adequate coping strategies | |||

| Usually | – | – | – |

| Often | 1.7 | 0.2–17.6 | 0.67 |

| Few | 8.9 | 1.1–75.3 | 0.05 |

| Not at all | 25.0 | 2.7–231.1 | 0.01 |

Bold letters indicate a significant p value.

Several studies have examined the impact of COVID-19 on mental health among healthcare workers17–22; however, only a few studies have been conducted in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). To our knowledge, this is the first study of oncology care providers from Latin America to specifically assess the psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

We found spreading COVID-19 instead of getting infected as the major sources of stress except for those with longer working experience (30 years and over); the latter may be related to their higher risk for complications given their older age (Table 3). In general, studies among healthcare providers have shown a personal sense of higher responsibility for preventing the spread of the virus.23–27 Other studies have also found that financial concerns and other stressors, not COVID-19 infection, are the major source of distress19,28; however, most were carried out among the general population and were not specific to healthcare workers or other occupations.

Financial concerns as a source of stress among oncology care providers in our study are interesting and might reflect either the type of employment with no stable relationship with their respective institutions or a high dependency for family income beyond their own employment, both factors that could be different from high-income countries. Previous studies from Latin America, including healthcare providers, but not specifically oncology care, have found relevant differences by type of provider (doctors versus others)29; however, we did not find such differences in our study.

A low prevalence of depression and anxiety, low levels of moral distress, and normal levels of resilience were observed in our study (Table 2). In contrast, reports of Latin American healthcare workers were not consistent, showing higher levels of anxiety and depression in Chilean populations,30 but lower levels in Peruvian populations29 and among Hispanic American otolaryngologists.31 Oncology care providers regularly have a higher psychological burden,32–34 thus resulting in a more frequent manifestation of anxiety and depression35,36; however, it is possible that during the pandemic, following its sudden onset, common exposure to acute stressors induces a similar response among all healthcare workers without major distinctions by specialty or level of training.23,37,38

Moral distress occurs when a person cannot act the way they believe is ethically appropriate.39 Care providers with longer working experience, divorcees, those working in non-comprehensive centers, and those without coping strategies reported high levels of moral distress (Table 2); however, only a history of depression showed a statistically significant increase. Oncology care was prioritized in Colombia during the pandemic, and ethical dilemmas, such as deferring treatment, changing protocols, and referrals to intensive care units, were faced on a case-by-case basis at institutions by following national and international consensus guidelines without placing a great burden on individuals for decisions.

Significant differences were observed between women and men regarding resilience and depression/anxiety with higher and lower scores for the latter, respectively. Although previous studies have shown higher resilience among Latin American women,40 the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and working and work/life disparities for women in a society without gender equity should also be considered as possible factors explaining the difference in our study. In addition, women regularly have a higher prevalence of depression/anxiety,41–44 and unlike resilience, the COVID-19 pandemic worsened the wellbeing of women, a finding already reported in health workers from Latin America.29

In Colombia, in common with the rest of Latin America, most nurses are women; however, unlike previous reports the average PHQ-4 score was higher for medical specialists than for nurses.41,44,45 We did not analyze responses by sex of the medical specialists, and the multivariate analysis also did not show a significant association between these variables.

Besides sex, only a history of depression and having no coping strategies were significantly associated with a high level of depression/anxiety, a result attributable to vulnerability arising from previous depressive episodes,35,46,47 the lack of personal resources to manage mental distress,48 and the exacerbation of mental health symptoms during the pandemic.36

Our study has some limitations. Specifically, the sample size and the sampling method could introduce a selection bias with greater participation in better mental health conditions. In addition, despite the internal consistency indices being similar to those observed in Colombian validations of the instruments used,49–51 these validations have not been done specifically for oncology care providers. Finally, the lack of pretest measures of psychological variables limits further interpretations of our findings. To obtain a significant number of participants, we carried out the study during a 6-month period after the beginning of the national confinement, thus covering a progressive instauration of the pandemic and the end of the first wave in August; it is possible that restricting the study to a shorter period in recent phases of the pandemic would result in different outcomes.51

Despite its limitations, we think our study will be useful in helping design preventive measures during future emergencies with a potential impact on oncology care, given the special and vulnerable condition of oncology patients and the associated stress on oncology care providers. Indeed, we found 46.7% of care providers with a ‘few’ or ‘not at all’ coping strategies indicating a need for oncology care provider education. In general, we believe that growing information about the mental health of oncology care providers allows for better implementation of preventive measures to promote their psychological wellbeing. Furthermore, a complementary approach using mental health parameters objectively during periods with no crises is highly desirable.

Data availability statementThe data that support the findings of this study are openly available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/q7dha/?view_only=3e0c8a02ac604b428fa3fd68e261753b, in the folder “Data set”.

FundingThe authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.